Creating a Governing Framework for Public Education in New Orleans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

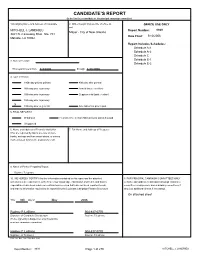

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU Report Number: 9939 Mayor - City of New Orleans 3421 N. Casueway Blvd. Ste. 701 Date Filed: 5/10/2006 Metairie, LA 70002 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule C 3. Date of Election Schedule E-1 Schedule E-2 This report covers from 4/3/2006 through 4/30/2006 4. Type of Report: 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary X 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more banks, savings and loan associations, or money market mutual fund as the depository of all 9. Name of Person Preparing Report Daytime Telephone 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. Name and address of principal campaign committee, expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, committee’s chairperson, and subsidiary committees, if and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure any (use additional sheets if necessary). -

Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 12-17-2010 Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans Nicole Romagossa University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Romagossa, Nicole, "Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans" (2010). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1245. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1245 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Public History by Nicole Romagossa B.A. Louisiana State University, 2008 December 2010 Acknowledgments Thank you to my thesis committee, Dr. Molly Mitchell, Dr. Connie Atkinson, and Dr. -

Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter As Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Seeing and Then Seeing Again: Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter as Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J. Bellocq and George Valentine Dureau A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Timothy J. Lithgow December 2019 Thesis Committee: Dr. Johannes Endres, Co-Chairperson Dr. Elizabeth W. Kotz, Co-Chairperson Dr. Keith M. Harris Copyright by Timothy J. Lithgow 2019 The Thesis of Timothy J. Lithgow is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements: Thank you to Keith Harris for discussing George Dureau on the first day of class, and for all his help since then. Thank you to Liz Kotz for conveying her clear love of Art History, contemporary arts and artists. Although not on my committee, thank you to Jeanette Kohl, for her thoughtful and nuanced help whenever asked. And last, but certainly not least, a heartfelt thank you to Johannes Endres who remained calm when people talked out loud during the quiz, who had me be his TA over and over, and who went above and beyond in his role here. iv Dedication: For Anita, Aubrey, Fiona, George, Larry, Lillian, Myrna, Noël and Paul. v Table of Contents Excerpt from Pentimento by Lillian Hellman ......................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: Biographical Information for Dureau and Bellocq .......................... 18 Table 1 ...................................................................................................... 32 Excerpt from One Arm by Tennessee Williams.................................................... 34 Chapter 2: Colonial Foundations of Libertine Tolerance in New Orleans, LA .. -

RG 68 Master Calendar

RG 68 MASTER CALENDAR Louisiana State Museum Historical Center Archives May 2012 Date Description 1387, 1517, 1525 Legal document in French, Xerox copy (1966.011.1-.3) 1584, October 20 Letter, from Henry IV, King of France, to Francois de Roaldes (07454) 1640, August 12 1682 copy of a 1640 Marriage contract between Louis Le Brect and Antoinette Lefebre (2010.019.00001.1-.2) 1648, January 23 Act of sale between Mayre Grignonneau Piqueret and Charles le Boeteux (2010.019.00002.1-.2) 1680, February 21 Photostat, Baptismal certificate of Jean Baptoste, son of Charles le Moyne and marriage contract of Charles le Moyne and Catherine Primot (2010.019.00003 a-b) 1694 Reprint (engraving), frontspiece, an Almanack by John Tulley (2010.019.00004) c. 1700-1705 Diary of Louisiana in French (2010.019.00005 a-b) c. 1700 Letter in French from Philadelphia, bad condition (2010.019.00006) 1711, October 18 Document, Spanish, bound, typescript, hand-illustrated manuscript of the bestowing of a title of nobility by Charles II of Spain, motto on Coat of Arms of King of Spain, Philippe V, Corella (09390.1) 1711, October 18 Typescript copy of royal ordinance, bestows the title of Marquis deVillaherman deAlfrado on Dr. Don Geronina deSoria Velazquez, his heirs and successors as decreed by King Phillip 5th, Spain (19390.2) 1714, January 15 English translation of a letter written at Pensacola by M. Le Maitre, a missionary in the country (2010.019.00007.1-.29) 1714 Document, translated into Spanish from French, regarding the genealogy of the John Douglas de Schott family (2010.019.00008 a-b) 1719, December 29 Document, handwritten copy, Concession of St. -

I:\2016==GR Sharma Formating Jo

Journal of Criminal Justice and Law Review Vol. 5 • Nos. 12 • JanuaryDecember 2016 Racial slavery, that “peculiar institution” of the American South, has proven to be one of the United States’ most enduring. In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, it was repackaged and re-articulated as a convict underclass. The justification for the marginalization of that convict underclass, a group I refer to as the “criminal caste,” was often articulated in the same terms that had been used to justify racial slavery, a pattern that reflected an underlying commitment to white supremacy. The purpose of this article is to examine the role of historical white supremacy, articulated through colorism and the systematic denigration of blackness, in the construction of a criminal caste in New Orleans. As historian Adam Rothman observed, the Americans who moved west from Virginia and the Carolinas to settle the fertile lands of the Lower Mississippi River Valley, took their values with them as they sought to transmute the wild frontier of Louisiana into “slave country” (Rothman, 2007). Central to those values was a racialized caste system that stipulated black bondage as a necessary counterpoint to white liberty. The internal logic of that caste system demanded that where whiteness signified privilege, blackness necessarily signified subordination; where whiteness signified virtue, blackness signified degeneracy and brutishness. Where whites signified, as a group, the American citizenry, blacks (and non-white people, more generally) signified subjects of the American state, separate from the body politic and unfit for citizenship. This sensibility was, in fact, articulated explicitly by Chief Justice Roger B. -

1 Record Group 1 Judicial Records of the French

RECORD GROUP 1 JUDICIAL RECORDS OF THE FRENCH SUPERIOR COUNCIL Acc. #'s 1848, 1867 1714-1769, n.d. 108 ln. ft (216 boxes); 8 oversize boxes These criminal and civil records, which comprise the heart of the museum’s manuscript collection, are an invaluable source for researching Louisiana’s colonial history. They record the social, political and economic lives of rich and poor, female and male, slave and free, African, Native, European and American colonials. Although the majority of the cases deal with attempts by creditors to recover unpaid debts, the colonial collection includes many successions. These documents often contain a wealth of biographical information concerning Louisiana’s colonial inhabitants. Estate inventories, records of commercial transactions, correspondence and copies of wills, marriage contracts and baptismal, marriage and burial records may be included in a succession document. The colonial document collection includes petitions by slaves requesting manumission, applications by merchants for licenses to conduct business, requests by ship captains for absolution from responsibility for cargo lost at sea, and requests by traders for permission to conduct business in Europe, the West Indies and British colonies in North America **************************************************************************** RECORD GROUP 2 SPANISH JUDICIAL RECORDS Acc. # 1849.1; 1867; 7243 Acc. # 1849.2 = playing cards, 17790402202 Acc. # 1849.3 = 1799060301 1769-1803 190.5 ln. ft (381 boxes); 2 oversize boxes Like the judicial records from the French period, but with more details given, the Spanish records show the life of all of the colony. In addition, during the Spanish period many slaves of Indian 1 ancestry petitioned government authorities for their freedom. -

A History of Theatre in New Orleans from 1925 to 1935. Melvin Howard Berry Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 A History of Theatre in New Orleans From 1925 to 1935. Melvin Howard Berry Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Berry, Melvin Howard, "A History of Theatre in New Orleans From 1925 to 1935." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2446. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2446 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Street Renaming Commission

NEW ORLEANS CITY COUNCIL STREET RENAMING COMMISSION FINAL REPORT March 1, 2021 FINAL REPORT MARCH 1, 2021 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary 02 Letter from the Chair 04 Introduction 05 New Orleans City Council Approved Motion 06 M-20-170 and Commission Charge City Council Streets Renaming Commission 07 Working Group Policy Impacting Naming and Removal of 10 Assets Assets: Defined and Prioritized 13 Summary of Engagement Activities (Voices 14 from New Orleans Residents) City Council Street Renaming Commission 22 Final Recommendations Appendix / Reference Materials 38 Commission Meeting Public Comments 42 Website Public Comments 166 NEW ORLEANS CITY COUNCIL STREET RENAMING COMMISSION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On June 18, 2020, the New Orleans City Council unanimously voted to establish the City Council Street Renaming Commission (CCSRC) as an advisory committee to run a public process for making recommendations to rename streets, parks, and places in New Orleans that honor white supremacists. The CCSRC is composed of nine total members, with one appointed by each Councilmember with a formal or informal background of the history and geography of New Orleans. Mayor LaToya Cantrell and the City Planning Commission appointed the remaining two members. The Commission was charged with several key responsibilities, which included conducting a thorough research and public engagement process to develop a comprehensive set of renaming recommendations for streets, parks, and places across the city. In the course of auditing the list of City streets beyond those initially identified by the New Orleans Public Library, the Commission consulted a panel of experts to provide an additional set of names, which was used to formulate the recommendations listed in this report. -

Ernest N. “Dutch” and His Son Marc, Each Had a Lasting Legacy in New Orleans — Though Both Legacies Are Marked by Dissent and Controversy

NEW ORLEANS From Bienville to Bourbon Street to bounce. 300 moments that make New Orleans unique. WHAT HAPPENED Ernest “Dutch” 1718 ~ 2018 Morial became the city’s first black mayor 300 on May 2, 1978. TRICENTENNIAL The Morials — Ernest N. “Dutch” and his son Marc, each had a lasting legacy in New Orleans — though both legacies are marked by dissent and controversy. “Dutch” Morial who succeeded him as mayor. He refused became New to bow to demands in a police strike in 1979, Orleans’ first which effectively canceled Mardi Gras. black mayor in “I think he will also be remembered for 1978 and served his tenacity and pugnaciousness. He was THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE two terms. He certainly controversial, and I think will THE NEW ORLEANS HISTORIC COLLECTION was also the first be remembered for that also, and very African-Amer- fondly by some,” said former Mayor Moon The second term of Marc Morial, shown in ican graduate Landrieu after Dutch died in 1989. 1998, ended in 2002 and was tainted by an in- vestigation into his administration’s contracts. from Louisiana Marc Morial also Both Dutch and Marc Morial State Univer- clashed with the City tried to get the public to agree sity’s law school; Council as he worked to to lift term limits so they could the first black balance the city’s budget, run for a third term. assistant U.S. at- and led efforts to create LOYOLA UNIVERSITY Lolis Elie, Rev. torney in Louisiana; the first black Louisiana an ethics board and in- THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE A.L. -

Playing the Big Easy: a History of New Orleans in Film and Television

PLAYING THE BIG EASY: A HISTORY OF NEW ORLEANS IN FILM AND TELEVISION Robert Gordon Joseph A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Cynthia Baron, Advisor Marlise Lonn Graduate Faculty Representative Clayton Rosati Andrew Schocket © 2018 Robert Joseph All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Cynthia Baron, Advisor Existing cultural studies scholarship on New Orleans explores the city’s exceptional popular identity, often focusing on the origins of that exceptionality in literature and the city’s twentieth century tourism campaigns. This perceived exceptionality, though originating from literary sources, was perpetuated and popularized in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries by film and television representations. As Hollywood’s production standards evolved throughout the twentieth century, New Orleans’ representation evolved with it. In each filmmaking era, representations of New Orleans reflected not only the production realities of that era, but also the political and cultural debates surrounding the city. In the past two decades, as the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the passage of film tax credits by the Louisiana Legislature increased New Orleans’ profile, these debates have been more present and driven by New Orleans’ filmed representations. Using the theoretical framework of Guy Debord’s spectacle and the methodology of New Film History and close “to the background” textual analysis, this study undertakes an historical overview of New Orleans’ representation in film and television. This history starts in the era of Classical Hollywood (1928-1947) and continues through Transitional Hollywood (1948-1966), New Hollywood (1967-1975), and the current Age of the Blockbuster (1975-). -

Articles for TOGETHER Teaching Guide

OTHER GROUPS THAT ARE BRINGING PEOPLE TOGETHER In addition to those listed in the AFTERWORD of the book TOGETHER by Amy Nathan Mary Turner Project http://www.maryturner.org/mtp.htm The Mary Turner Project (MTP) is a diverse, grassroots volunteer collective of students, educators, and community members who are committed to racial justice and racial healing. That commitment involves educating ourselves and others about the presence of racism, the multiple forms of racism, and the effects of racism, so that we may become involved in eliminating racism. Much of our work centers on research driven community engagement and action relevative to past and current racial injustice. The first of those includes the creation of a free, searchable, web based database on U.S. slavery. The second initiative involves the creation of a free, searchable database on all known lynchings in the U.S. And our third initiative involves a collaborative campaign to engage state sponsored Confederate culture in Georgia. As part of our ongoing work, the MTP also organizes an annual Mary Turner Commemoration each May. That multiracial, multigenerational event is attended by people from all over the country. It involves a shared meal, a short program, reflections from the descendants of the 1918 lynching victims, and a caravan out to the site of Mary Turner's murder. There the group shares thoughts, poetry, song and prayers. The public is always invited to this historic event which takes place in Hahira, Georgia. Below are a few scenes from the 2010 gathering. For more information about this event simply send us an email. -

Pdf/TCR-AL122005 Katrina.Pdf (Accessed July 30, 2014)

JUHXXX10.1177/0096144215576332Journal of Urban HistoryKlopfer 576332research-article2015 Article Journal of Urban History 2017, Vol. 43(1) 115 –139 “Choosing to Stay”: Hurricane © The Author(s) 2015 Reprints and permissions: Katrina Narratives and the History sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0096144215576332 of Claiming Place-Knowledge in juh.sagepub.com New Orleans Anja Nadine Klopfer1 Abstract Oral histories of the Hurricane Katrina experience abound in stories of conscious decisions to “ride out the storm.” My article explores the narrative of “choosing to stay” as an empowering narrative rooted in assertions of place-knowledge and traces its historical genealogy to the nineteenth century. I argue that claiming agency in New Orleans and articulating a sense of belonging and local identity through professed intimate knowledge of the local environment took shape as a strategy of resistance against dominant discourses of American progress after the Civil War. Ultimately, this counternarrative of connecting to place as “homeland,” drawing on knowledge arising from lived experience, defied the normative twist of modernization, simultaneously reformulating power relations within the city. “Choosing to stay” thus turns out to be a long-lasting narrative not only of disaster, but of place, belonging, and community; without understanding its historical layers, we cannot fully make sense of this particular Katrina narrative. Keywords Hurricane Katrina, disaster narratives, nineteenth-century New Orleans, levees, Creole history, environmental knowledge, flood prevention Introduction I am not leaving New Orleans, Louisiana. I was born here in 1963 on December 24th. And this is where the f*** I’m gonna die, whether you try to drown me or I die naturally.