Bienville's Dilemma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He an T Ic Le

June/July 2018 From The Dean . “Today is the beginning. Today is the first day of what’s next – the first day of a new era for our city. A city open to all. A city that embraces everyone, and gives every one of her children a chance.... You don’t quit on your families, and we - we are not going to quit on you. We are going to embrace all families, regardless of what that family looks like. We talk about how much we love our city. We talk about it. But I am calling upon each one of you, on every New Orleanian … to speak out — and show the same love for the people of our city.” -Mayor LaToya Cantrell May 7, 2018 The Church exists to be a beacon of God’s love for humanity, and a safe place for all people to come and seek this love. The Feast of Pentecost, which comes 50 days after Easter, commemorates the outpouring of the Holy Spirit upon the followers of the Way of Jesus. At this moment they were, and by extension we are, sent into the World to make disciples and claim the gifts that the Holy Spirit has bestowed upon each of us. We are called to work with all people to build the beloved community in the places where we live and move and have our being. For many of the members of Christ Church Cathedral that place is the City of New Orleans. One of my first official responsibilities upon becoming Dean was to represent Bishop Charles Jenkins at the inauguration of Mayor Ray Nagin in the Superdome in May of 2002. -

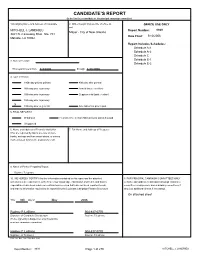

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU Report Number: 9939 Mayor - City of New Orleans 3421 N. Casueway Blvd. Ste. 701 Date Filed: 5/10/2006 Metairie, LA 70002 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule C 3. Date of Election Schedule E-1 Schedule E-2 This report covers from 4/3/2006 through 4/30/2006 4. Type of Report: 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary X 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more banks, savings and loan associations, or money market mutual fund as the depository of all 9. Name of Person Preparing Report Daytime Telephone 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. Name and address of principal campaign committee, expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, committee’s chairperson, and subsidiary committees, if and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure any (use additional sheets if necessary). -

Banquettes and Baguettes

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Banquettes and Baguettes “In the city’s early days, city blocks were called islands, and they were islands with little banks around them. Logically, the French called the footpaths on the banks, banquettes; and sidewalks are still so called in New Orleans,” wrote John Chase in his immensely entertaining history, “Frenchmen, Desire Good Children…and Other Streets of New Orleans!” This was mostly true in 1949, when Chase’s book was first published, but the word is used less and less today. In A Creole Lexicon: Architecture, Landscape, People by Jay Dearborn Edwards and Nicolas Kariouk Pecquet du Bellay de Verton, one learns that, in New Orleans (instead of the French word trottoir for sidewalk), banquette is used. New Orleans’ historic “banquette cottage (or Creole cottage) is a small single-story house constructed flush with the sidewalk.” According to the authors, “In New Orleans the word banquette (Dim of banc, bench) ‘was applied to the benches that the Creoles of New Orleans placed along the sidewalks, and used in the evenings.’” This is a bit different from Chase’s explanation. Although most New Orleans natives today say sidewalks instead of banquettes, a 2010 article in the Time-Picayune posited that an insider’s knowledge of New Orleans’ time-honored jargon was an important “cultural connection to the city”. The article related how newly sworn-in New Orleans police superintendent, Ronal Serpas, “took pains to re-establish his Big Easy cred.” In his address, Serpas “showed that he's still got a handle on local vernacular, recalling how his grandparents often instructed him to ‘go play on the neutral ground or walk along the banquette.’” A French loan word, it comes to us from the Provençal banqueta, the diminutive of banca, meaning bench or counter, of Germanic origin. -

Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 12-17-2010 Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans Nicole Romagossa University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Romagossa, Nicole, "Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans" (2010). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1245. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1245 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Public History by Nicole Romagossa B.A. Louisiana State University, 2008 December 2010 Acknowledgments Thank you to my thesis committee, Dr. Molly Mitchell, Dr. Connie Atkinson, and Dr. -

Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter As Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Seeing and Then Seeing Again: Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter as Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J. Bellocq and George Valentine Dureau A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Timothy J. Lithgow December 2019 Thesis Committee: Dr. Johannes Endres, Co-Chairperson Dr. Elizabeth W. Kotz, Co-Chairperson Dr. Keith M. Harris Copyright by Timothy J. Lithgow 2019 The Thesis of Timothy J. Lithgow is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements: Thank you to Keith Harris for discussing George Dureau on the first day of class, and for all his help since then. Thank you to Liz Kotz for conveying her clear love of Art History, contemporary arts and artists. Although not on my committee, thank you to Jeanette Kohl, for her thoughtful and nuanced help whenever asked. And last, but certainly not least, a heartfelt thank you to Johannes Endres who remained calm when people talked out loud during the quiz, who had me be his TA over and over, and who went above and beyond in his role here. iv Dedication: For Anita, Aubrey, Fiona, George, Larry, Lillian, Myrna, Noël and Paul. v Table of Contents Excerpt from Pentimento by Lillian Hellman ......................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: Biographical Information for Dureau and Bellocq .......................... 18 Table 1 ...................................................................................................... 32 Excerpt from One Arm by Tennessee Williams.................................................... 34 Chapter 2: Colonial Foundations of Libertine Tolerance in New Orleans, LA .. -

God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame After Katrina Jefferson Walker University of Southern Mississippi, [email protected]

Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal Volume 41 Combined Volume 41/42 (2014/2015) Article 4 January 2014 God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame after Katrina Jefferson Walker University of Southern Mississippi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/ctamj Part of the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Walker, J. (2014/2015). God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame after Katrina. Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal, 41/42, 29-48. This General Interest is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Walker: God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame after Katrina CTAMJ 2014/2015 29 GENERAL INTEREST ARTICLES God, Gays, and Voodoo: Voicing Blame after Katrina Jefferson Walker Visiting Instructor, Department of Communication Studies University of Southern Mississippi [email protected] Abstract Much of the public discourse following Hurricane Katrina’s devastating impact on Louisiana and much of the Gulf Coast in 2005 focused on placing blame. This paper focuses on those critics who stated that Hurricane Katrina was “God’s punishment” for people’s sins. Through a narrative analysis of texts surrounding Hurricane Katrina, I explicate the ways in which individuals argued about God’s judgment and punishment. I specifically turn my attention to three texts: First, a Repent America press release entitled “Hurricane Katrina Destroys New Orleans Days Before ‘Southern Decadence,’” second, a newsletter released by Rick Scarborough of Vision America, and third, Democratic Mayor of New Orleans, Ray Nagin’s “Chocolate City” Speech. -

Collection Uarterly

VOLUME XXXVI The Historic New Orleans NUMBERS 2–3 SPRING–SUMMER Collection uarterly 2019 Shop online at www.hnoc.org/shop VIEUX CARRÉ VISION: 520 Royal Street Opens D The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly ON THE COVER The newly expanded Historic New Orleans B Collection: A) 533 Royal Street, home of the Williams Residence and Louisiana History Galleries; B) 410 Chartres Street, the Williams Research Center; C) 610 Toulouse Street, home to THNOC’s publications, marketing, and education departments; and D) the new exhibition center at 520 Royal Street, comprising the Seignouret- Brulatour Building and Tricentennial Wing. C D photo credit: ©2019 Jackson Hill A CONTENTS 520 ROYAL STREET /4 Track the six-year planning and construction process of the new exhibition center. Take an illustrated tour of 520 Royal Street. Meet some of the center’s designers, builders, and artisans. ON VIEW/18 THNOC launches its first large-scale contemporary art show. French Quarter history gets a new home at 520 Royal Street. Off-Site FROM THE PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT COMMUNITY/28 After six years of intensive planning, archaeological exploration, and construction work, On the Job: Three THNOC staff members as well as countless staff hours, our new exhibition center at 520 Royal Street is now share their work on the new exhibition open to the public, marking the latest chapter in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s center. 53-year romance with the French Quarter. Our original complex across the street at 533 Staff News Royal, anchored by the historic Merieult House, remains home to the Williams Residence Become a Member and Louisiana History Galleries. -

This Book Is Dedicated to the People of New Orleans. I Have Not Forgotten Your Struggle

This Book is dedicated to the people of New Orleans. I have not forgotten your struggle. i I want to also dedicate this book to Rachel. I am truly blessed to have had her by my side throughout this wild adventure. ii Table of Contents Chapter 1 N.O.L.A.. 1 Jazz. 12 Mardi Gras. 14 Balconies. 16 Chapter 2 My First Visit. 19 Bourbon Street. 20 Haunted History. 22 Marie Laveau . 24 Lafitte’s Blacksmith Shop. 28 Chapter 3 My Second Visit. .31 Hotel Monteleone. 32 Jackson Square. 36 Pirate’s Alley. 38 French Market. 40 Café du Mondé . 42 The Riverwalk. 44 Pat O’Briens. 46 iii Chapter 4 Hurricane Katrina. 49 August 29 , 2005 . 50 Philip. 54 Chapter 5 My Third Visit. 59 Rebirth . 60 The French Quarter. 62 9th Ward. .64 Lake Pontchartrain . 68 Mississippi - Gulf of Mexico . 72 The Frenchmen Hotel. 76 The Court of Two Sisters . .78 Signs . 80 Water Towers.. 86 iv Appendixes Appendix A.. ��������������������������������������������������������������� 91 Appendix B.. ���������������������������������������������������������������97 Appendix C.. ���������������������������������������������������������������99 Appendix D. 100 Index . .101 One of the many Katrina Memorial Fleur-de-Lis’ dedicated around New Orleans. v All Fleur-de-lis’ are hand painted by local artists. vi Chapter X1 N.O.L.A. XXXXXXXXXXXXNew Orleans, Louisiana In 1682, Frenchmen Robert de La Salle sailed the Mississippi River and erected a cross somewhere near the location of New Orleans. He claimed Louisiana for his king, Louis XIV. The first French settlements were established on the Gulf Coast at Biloxi. Thirty-six years later, Jean Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville established a settlement on the Lower Mississippi River at New Orléans. -

Saint Denis in New Orleans

A SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR OF NEW ORLEANS & THE LOCATIONS THAT INSPIRED RED DEAD REDEMPTION 2 1140 Royal St. 403 Royal St. Master Nawak Master Nawak We start at Bastille In the mission “The Joys Next up is the Lemoyne the RDR2 storyline. Saloon, the lavish, of Civilization”, Arthur National Bank, a grand three-storied social Morgan stops here to and impressive In the mission, The Louisiana State Bank epicenter of Saint gather intel on Angelo The infamous LaLaurie representation of the “Banking, The Old serves as a real life mirror Denis, made exclusive Bronte, the notorious Mansion is a haunted largest developed city American Art”, Dutch landmark in the French to its fictitious counterpart to the upper echelons of Italian crime lord of in the country. and Hosea round up the Quarter. Madame LaLaurie in both design and purpose. gang for one last heist, society by its wealthy, Saint Denis. He is was a distinguished Creole According to Wikipedia, “the Established in 1763, a final attempt to well-to-do patrons. cautioned by the wary socialite in the early 1800’s, Louisiana State Bank was bartender to abandon later discovered to be a Saint Denis’ stateliest procure the cash they founded in 1818, and was Will you: play a dangerous waters... serial killer and building is older than need in order to start the first bank established in spirited, high-stakes slave torturer. the country itself. over as new men in a the new state of Louisiana game of poker with a This is also the only When her despicable crimes Heiresses and captains free world. -

Garden District Accommodations Locator

GARDEN DISTRICT ACCOMMODATIONSJefferson LOCATOR Leontine Octavia BellcastleValmont Duffosat MAP #/PROPERTY/NUMBER OF ROOMS Soniat MAGAZINE Robert GARDEN DISTRICT/UPTOWN STREET LyonsUpperline 1. Avenue Plaza Resort/50 Bordeaux 2. Best Western St. Charles Inn/40 Valence 3. Columns Hotel/20 Cadiz 4. Hampton Inn – Garden District/100 Jena 5. Hotel Indigo New Orleans - Garden District/132 Tchoupitoulas 6. Maison St. Charles Quality Inn & Suites/130 General PershingNapoleonUPTOWN 7. Prytania Park Hotel/90 Marengo Milan Annunciation Laurel Camp Constance GEOGRAPHY ConstantinopleChestnut Coliseum New Orleans encompasses 4,190 square miles or Austerlitz Perrier Gen. Taylor Prytania 10,850 square kilometers and is approximately 90 Pitt Peniston miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River. Carondelet Amelia St.Charles Av Magazine Baronne Antonine CLIMATE Foucher 3 2 New Orleans has a subtropical climate with pleasant Aline 4 year-round temperatures. Temperatures range from Delachaise mid-40°F (7°C) in winter to more than 90°F (32°C) ST. CHARLES in the summer. Rainfall is common in New Orleans, Louisiana with a monthly average of about five inches (12.7 cm) Toledano AVENUE Pleasant of precipitation. 9th Harmony 8th AVERAGE TEMPERATURES AVG. RAINFALL MONTH MAX {°F/°C} MIN {°F/°C} 7th {IN/CM} Camp Jan. 63/17 43/6 4.9/12.4 6th Chestnut Prytania Coliseum Constance Feb. 64/18 45/7 5.2/13.2 Magazine Conery March 72/22 52/11 4.7/11.9 Washington April 79/26 59/15 4.5/11.4 GARDEN 4th May 84/29 64/18 5.1/13.0 June 90/32 72/22 4.6/11.7 DISTRICT 3rd July 91/33 73/23 6.7/17.0 2nd S. -

MACCNO Street Performer's Guide

Know your stories background In 1956 a Noise ordinance was implemented to dictate... Through a rights when I’m a full time resident of the French Quarter who series of amendments and changes the ordinance is struggling would like to see more opportunities for our musicians to reach a healthy balance which respects residents while both on the street and in the restaurants and clubs. preserving New Orleans’ historic and unique music culture. performing: Street musicians are an integral part of the Quarter *Taken from the New Orleans Code of Ordinances and appreciated by many including a lot of the residents. That said we do need to educate residents, GUIDE TO businesses and musicians about the complexities of . performing on the streets of the Quarter. With a little 1959 give and take by all stakeholders we should be able to First unified city code bans NEW ORLEANS peacefully co-exist and prosper in this unique part of musicians from playing on city in the City. streets from 8 pm to 9 pm. any public right of way, public park or recreational 1977 area as long as you don’t exceed an average of City ordinance prohibiting I’m a community organizer and a lifelong advocate street performance on STREET measured at from the source. for many of the cultural groups in this city. I believe 1981 Royal St declared (Sec 66-203) that groups like the Mardi Gras Indians, Social Aid Unified city code is amended unconstitutional. & Pleasure Clubs, and brass bands are not fully to include a noise policy that utilizes decibel sound levels. -

New Orleans and the LRA

Lighting The Road To Freedom Data Zone Page 13 Emmanuel Jal: Soldier For Peace “The People’s Paper” October 7, 2006 40th Year Volume 36 www.ladatanews.com The Soul of New Orleans A Long Road Home: New Orleans and the LRA Page 3 Newsmaker Congressional Race Heats Up Amaju Barak to speak Inside Data| at Tulane Page 6 Page 5 4HEULTIMATETRIPFORTHEULTIMATECIRCLEOFFRIENDS Pack your bags and go in style with the Girlfriends L.A. Getaway. Enter for your chance to win a trip to glamorous Los Angeles, California. Plus sensational sights, shopping and spa treatment for you and three of your best girls! come and get your loveSM SM— call anyone on any network for free. Visit alltelcircle.com for details. Alltel Retail Stores These Retail Stores Now Open Sunday. Authorized Agents Equipment & promotional offers at these locations may vary. Covington Kenner Slidell Destrehan LaPlace Nationwide Comm. Marrero Metairie 808 Hwy. 190, Ste. B 1000 W. Esplanade Ave. 1302 Corporate Sq., Ste. 2016 NexGeneration Superior Comm. 2003 Florida St. V. Telecom Bobby April Wireless (985) 893-7313 (504) 468-8334 (985) 847-0891 12519 Airline Hwy. 1819 W. Airline Hwy. (985) 626-1282 5001 Lapalco Blvd. 1700 Veterans blvd., Ste. 300 (985) 764-2021 (985) 652-6659 (504) 349-4912 (504) 835-9600 Houma Larose Shop at a Participating 1043 W. Tunnel Blvd. 115 W. 10th St. Gretna Mandeville (985) 851-2355 (985) 798-2323 Cell Phone Depot Nationwide Comm. 2112 Belle Chase Hwy., Ste. 2 1876 N. Causeway Blvd. Official Wireless Provider Proud Sponsor of: Southland Mall Metairie (504) 433-1921 (985) 626-1272 5953 W.