Articles for TOGETHER Teaching Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States Conference of Mayors 85Th Annual Meeting June 23-26, 2017 the Fontainebleau Hotel Miami Beach, Florida

The United States Conference of Mayors 85th Annual Meeting June 23-26, 2017 The Fontainebleau Hotel Miami Beach, Florida DRAFT AGENDA June 14, 2017 KEY INFORMATION FOR ATTENDEES Participation Unless otherwise noted, all plenary sessions, committee meetings, task force meetings, workshops and social events are open to all mayors and other officially-registered attendees. Media Coverage While the plenary sessions, committee meetings, task force meetings and workshops are all open to press registrants, please note all social/evening events are CLOSED to press registrants wishing to cover the meeting for their news agency. Resolution and Committee Deadline The deadline for submission of proposed resolutions by member mayors is May 24, 2017 at 5:00 pm EDT. This is the same deadline for standing committee membership changes. Members can submit resolutions and update committee memberships through our USCM Community web site at community.usmayors.org. Voting Only member mayors of a standing committee are eligible to vote on resolutions before that standing committee. Mayors who wish to record a no vote in a standing committee or the business session should do so within the mobile app. Title Sponsor: #uscm2017 1 Charging Stations Philips is pleased to provide charging stations for electronic devices during the 85th Annual Meeting in Miami Beach. The charging stations are located in the Philips Lounge, within the meeting registration area. Mobile App Download the official mobile app to view the agenda, proposed resolutions, attending mayors and more. You can find it at usmayors.org/app. Available on the App Store and Google Play. Title Sponsor: #uscm2017 2 FONTAINEBLEAU FLOOR PLAN Title Sponsor: #uscm2017 3 NOTICES (Official functions and conference services are located in the Fontainebleau Hotel, unless otherwise noted. -

The Tennessee -& Magazine

Ansearchin ' News, vol. 47, NO. 4 Winter zooo (( / - THE TENNESSEE -& MAGAZINE THE TENNESSEE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY 9114 Davies Pfmrauon Road on rhe h~srorkDa vies Pfanrarion Mailng Addess: P. O, BOX247, BrunswrCG, 737 38014-0247 Tefephone: (901) 381-1447 & BOARD MEMBERS President JAMES E. BOBO Vice President BOB DUNAGAN Contributions of all types of Temessee-related genealogical Editor DOROTEíY M. ROBERSON materials, including previously unpublished famiiy Bibles, Librarian LORElTA BAILEY diaries, journals, letters, old maps, church minutes or Treasurer FRANK PAESSLER histories, cemetery information, family histories, and other Business h4anager JOHN WOODS documents are welcome. Contributors shouid send Recording Secretary RUTH REED photocopies of printed materials or duplicates of photos Corresponding Secretary BEmHUGHES since they cannot be returned. Manuscripts are subject Director of Sales DOUG GORDON to editing for style and space requirements, and the con- Director of Certiñcates JANE PAESSLER tributofs narne and address wiU & noted in the publish- Director at Large MARY ANN BELL ed article. Please inciude footnotes in the article submitted Director at Large SANDRA AUSTIN and list additional sources. Check magazine for style to be used. Manuscripts or other editorial contributions should be EDITO-. Charles and Jane Paessler, Estelle typed or printed and sent to Editor Dorothy Roberson, 7 150 McDaniel, Caro1 Mittag, Jeandexander West, Ruth Reed, Belsfield Rd., Memphis, TN 38 119-2600. Kay Dawson Michael Ann Bogle, Kay Dawson, Winnie Calloway, Ann Fain, Jean Fitts, Willie Mae Gary, Jean Giiiespie, Barbara Hookings, Joan Hoyt, Thurman Members can obtain information fiom this file by writing Jackson, Ruth O' Donneii, Ruth Reed, Betty Ross, Jean TGS. -

HEARING AIDS I DON’T WEAR a HEARING AID? Missing Certain Sounds That Stimulate the Brain

“THE PEOPLE’S PAPER” VOL. 20 ISSUE 10 ~ July 2020 [email protected] Online: www.alabamagazette.com 16 Pages – 2 Sections ©2020 Montgomery, Autauga, Elmore, Crenshaw, Tallapoosa, Pike and Surrounding Counties 334-356-6700 Source: www.laserfiche.com Land That I Love: Restoring Our Christian Heritage An excerpt from Land That I Love by Bobbie Ames . “The story of the Declaration is a part of the story of a national legacy, but to understand it, it is necessary to understand as well its makers, the world they lived in, the conditions which produced them, the confidence which encouraged them, the indignities which humiliated them, the obstacles which confronted them, the ingenuity which helped them, the faith which sustained them, the victory which came to them. It is, in other words, a part, a very signal part of a civilization and a period, from which, unlike his Britannic Majesty, it makes no claim to separation. On the contrary, unsurpassed as it is, it takes its rightful place in the literature of democracy. For its primacy, is a primacy which derives from the experience which evoked it. It is imperishable because that experience is remembered.” See page 3B for the complete article and for the link to order your own copy of Land That I Love: Restoring Our Christian Heritage. Rotary Clubs Continue to Serve Primary Montgomery Sunrise Rotary Club hosts Runoff “kitchen shower” for the Salvation Army. July 14th See story on page 8A. Tom Mann, Lt. Farrington, LEASE OTE Ell White II and Neal Hughs P V ! were excited to receive items donated to the Salvation Army by For more information on the elections: the Montgomery Rotary Club. -

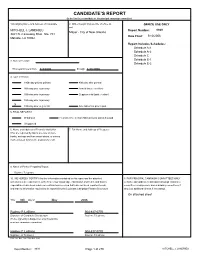

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU Report Number: 9939 Mayor - City of New Orleans 3421 N. Casueway Blvd. Ste. 701 Date Filed: 5/10/2006 Metairie, LA 70002 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule C 3. Date of Election Schedule E-1 Schedule E-2 This report covers from 4/3/2006 through 4/30/2006 4. Type of Report: 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary X 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more banks, savings and loan associations, or money market mutual fund as the depository of all 9. Name of Person Preparing Report Daytime Telephone 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. Name and address of principal campaign committee, expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, committee’s chairperson, and subsidiary committees, if and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure any (use additional sheets if necessary). -

Gender, Race, Class and the Professionalization of Nursing for Women in New Orleans, Louisiana, 1881-1950

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-18-2014 Crescent City Nightingales: Gender, Race, Class and the Professionalization of Nursing for Women in New Orleans, Louisiana, 1881-1950 Paula A. Fortier University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Fortier, Paula A., "Crescent City Nightingales: Gender, Race, Class and the Professionalization of Nursing for Women in New Orleans, Louisiana, 1881-1950" (2014). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1916. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1916 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Crescent City Nightingales: Gender, Race, Class and the Professionalization of Nursing for Women in New Orleans, Louisiana, 1881-1950 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Studies Urban History by Paula Anne Fortier B.A. -

View / Download 5.1 Mb

Nourishing Networks: The Public Culture of Food in Nineteenth-Century America by Ashley Rose Young Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laura Edwards, Supervisor ___________________________ Priscilla Wald ___________________________ Laurent Dubois ___________________________ Adriane Lentz-Smith Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 i v ABSTRACT Nourishing Networks: The Public Culture of Food in Nineteenth-Century America by Ashley Rose Young Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laura Edwards, Supervisor ___________________________ Priscilla Wald ___________________________ Laurent Dubois ___________________________ Adriane Lentz-Smith An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Ashley Rose Young 2017 Abstract “Nourishing Networks: The Public Culture of Food in Nineteenth-Century America” examines how daily practices of food production and distribution shaped the development of New Orleans’ public culture in the long nineteenth century, from the colonial era through the mid-twentieth century. During this period, New Orleans’ vendors labored in the streets of diverse neighborhoods where they did more than sell a vital commodity. As “Nourishing Networks” demonstrates, the food economy provided the disenfranchised—people of color, women, and recent migrants—a means to connect themselves to the public culture of the city, despite legal prohibitions intended to keep them on the margins. Those who were legally marginalized exercised considerable influence over the city’s public culture, shaping both economic and social interactions among urban residents in the public sphere. -

Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 12-17-2010 Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans Nicole Romagossa University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Romagossa, Nicole, "Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans" (2010). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1245. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1245 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Public History by Nicole Romagossa B.A. Louisiana State University, 2008 December 2010 Acknowledgments Thank you to my thesis committee, Dr. Molly Mitchell, Dr. Connie Atkinson, and Dr. -

Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter As Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Seeing and Then Seeing Again: Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter as Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J. Bellocq and George Valentine Dureau A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Timothy J. Lithgow December 2019 Thesis Committee: Dr. Johannes Endres, Co-Chairperson Dr. Elizabeth W. Kotz, Co-Chairperson Dr. Keith M. Harris Copyright by Timothy J. Lithgow 2019 The Thesis of Timothy J. Lithgow is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements: Thank you to Keith Harris for discussing George Dureau on the first day of class, and for all his help since then. Thank you to Liz Kotz for conveying her clear love of Art History, contemporary arts and artists. Although not on my committee, thank you to Jeanette Kohl, for her thoughtful and nuanced help whenever asked. And last, but certainly not least, a heartfelt thank you to Johannes Endres who remained calm when people talked out loud during the quiz, who had me be his TA over and over, and who went above and beyond in his role here. iv Dedication: For Anita, Aubrey, Fiona, George, Larry, Lillian, Myrna, Noël and Paul. v Table of Contents Excerpt from Pentimento by Lillian Hellman ......................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: Biographical Information for Dureau and Bellocq .......................... 18 Table 1 ...................................................................................................... 32 Excerpt from One Arm by Tennessee Williams.................................................... 34 Chapter 2: Colonial Foundations of Libertine Tolerance in New Orleans, LA .. -

Christmas Gifts Wedding Celebration

of marriages nevertheless, saw one of the prettiest weddings of the year last Wednesday at the Church of the Holy Name of Mary, when two of Al- AUTOMOBILE DIREgC Call up The Herald. Algiers 503, JA'n-r.enetrati*a giers' best and oldest families were will be arranged to ,. your conv • Fe The united through the marriage of John 1_Algerines at Law. Turner Morrison to Miss Gladys Short. Name of Car Distributor The church, and especially the sanctuary, were tastefully and beau. CIVIL DISTRICT COURT. Hlarding, lot Opelousas. Slidell. Belle- D.H.Holmes Co. tifully decorated. Fr. ('assagne had Succession of ienry P. Frazer. pos- ville and Vallette; another Iortion Reo "rI': 'nc Circle this in charge and as usual the re- session- E. A. Parsons. same square $:3t,0l terms --O'Connor. I------. - Limited suits were most gratifying to all pres- Emancipation of \\'alter Lee Frazer. State of Louisiana (James D)onnel- ent. judgment of emancipation. ly) to James l)onnelly. lot Webster. Circleod The bridal party entered the church Succession of Peter Clement. tutor- Wagnor. .\lix and Eliza $20 _t cash "t " (' announces its and marched down the main aisle to ship-Robt. O'Connor. IRedemption )-Treasurer. Premier the strains of Mendelsshon's Wedding CONVENTIONAL MORTGAGES. IHettye Levy ('ahn to Southern Park preparedness to .March. played by Prof. llerbert. lease of property No. 4"1 Mrs. .Jhn It. Norman to Bankers Itealty ('o.. 7 The bride looked charming and street corner Alix street, for S Loan & Securities ('o. Inc.. $1.'.(S1 Vallette Chalmers "I s serve you with digni,'ied. -

The-Lens-2017-Annual-Report.Pdf

1 THE LENS 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2017-18 LETTER FROM THE FOUNDER Ariella Cohen Who we are and what we do Roberta Brandes Gratz Jenel Hazlett John Joyce Life at a news operation like The Lens is as fast-paced as it is financially precarious. Friends and Beverly Nichols The Lens was founded in 2009, but the seeds of the organization date back to 2005, when the colleagues sometimes ask me where I find the energy to keep going year after year. Indeed, as we Martin C. Pedersen levees collapsed and New Orleans flooded in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. In many Harry Shearer near the end of a decade of reporting, I sometimes ask myself! ways, the recovery of New Orleans was a DIY effort based on the engagement, collaboration and ingenuity of its citizens. But the answer is right there in front of me every time I visit the site. It’s there in the astonishingly STAFF skillful and impactful work of our reporters and editors; it’s there in the daily ebb and flow of our audience metrics as readers — and public officials — dig into our journalism and respond to it. It’s Karen Gadbois, Founder The Lens grew out of that movement, with our commitment to give the people of New there in the continuing generosity of the foundations and private donors who support independent, Jed Horne, Opinion Editor Orleans the tools and information needed to watchdog a municipal government dealing with nonprofit journalism at a time of grave threats to American democracy. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

![Jambalaya [Yearbook] 1897](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0589/jambalaya-yearbook-1897-1580589.webp)

Jambalaya [Yearbook] 1897

m il, MBALAW :'!:'i'^fi Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/jambalayayearboo02edit IX]®Klo[B^K]E)^[L[L lLSLI (BD,CB©®I?3o iijjiiiAa>i.ii);iiWir3iiJ^inTj.i3- he ^sine (UrArit\/[1IVLR!)ITY. tW 0RLEAh>5,, La. Vol. n. ^^RESS OFL fiASHVILLE. I Ta tlir lUnnnnj of ^landall L,rr Gibson, Sulclicr, Statrsmnn, S-rliulnr, fxntl First "-('rrsitlrnt nf thr Buarri uf Ariininislnitnrs nf Tixlnne "ilniurrsitxj, this xiuhainr is rEspertfitlb tirtiicntetl. _f.i^_> PAGE Photo of Randall Lee Gibson, . Frontispiece Dedication, ........ 5 Biographical Sketch of Randall Lee Gibson, 9 Introduction, ....... II Facult}' and Instructors, ..... 13 Suniniar)' - - Faculty and Instructors, 15 Board of Administrators, ..... 16 Officers, ........ 16 Photo, Class of 1897, ...... 18 . Officers, Class of 1S97, . 19 History, Class of 1897, ...... 20 Statistics, Class of 1897, College of Arts and Sciences, 22 .Statistics, Class of r897. College of Technology, . 23 Photo, Class of 1898 24 Officers, Class of 1898, ...... 25 History, Class of 1898 26 Statistics, Class of 1898, College of Arts and Sciences, 28 Statistics, Class of iSg8, College of Technology, . 30 Photo, Class of 1899, ...... 32 Officers, Class of 1899, ...... 33 History, Class of 1899, ...... 34 Statistics, Class of 1899, College of Arts and Sciences, 36 Statistics, Class of 1899, College of Technology, . 38 Photo, Class of 1900, ...... 40 Officers, Class of 1900, ...... 41 History, Class of 1900, ...... 42 Statistics, Class of 1900, College of Arts and Sciences, 44 Statistics, Class of 1900, College of Technology, . 45 Special Students in Both Colleges, 47 University Department of Philosophy and Science, 48 The Medical Department, ....