I:\2016==GR Sharma Formating Jo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

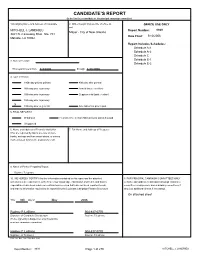

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU Report Number: 9939 Mayor - City of New Orleans 3421 N. Casueway Blvd. Ste. 701 Date Filed: 5/10/2006 Metairie, LA 70002 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule C 3. Date of Election Schedule E-1 Schedule E-2 This report covers from 4/3/2006 through 4/30/2006 4. Type of Report: 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary X 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more banks, savings and loan associations, or money market mutual fund as the depository of all 9. Name of Person Preparing Report Daytime Telephone 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. Name and address of principal campaign committee, expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, committee’s chairperson, and subsidiary committees, if and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure any (use additional sheets if necessary). -

Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 12-17-2010 Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans Nicole Romagossa University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Romagossa, Nicole, "Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans" (2010). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1245. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1245 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Albert Baldwin Wood, the Screw Pump, and the Modernization of New Orleans A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Public History by Nicole Romagossa B.A. Louisiana State University, 2008 December 2010 Acknowledgments Thank you to my thesis committee, Dr. Molly Mitchell, Dr. Connie Atkinson, and Dr. -

Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter As Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Seeing and Then Seeing Again: Empathy, Mood and the Artistic Milieu of New Orleans’ Storyville and French Quarter as Manifest by the Photographs and Lives of E.J. Bellocq and George Valentine Dureau A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Timothy J. Lithgow December 2019 Thesis Committee: Dr. Johannes Endres, Co-Chairperson Dr. Elizabeth W. Kotz, Co-Chairperson Dr. Keith M. Harris Copyright by Timothy J. Lithgow 2019 The Thesis of Timothy J. Lithgow is approved: Committee Co-Chairperson Committee Co-Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements: Thank you to Keith Harris for discussing George Dureau on the first day of class, and for all his help since then. Thank you to Liz Kotz for conveying her clear love of Art History, contemporary arts and artists. Although not on my committee, thank you to Jeanette Kohl, for her thoughtful and nuanced help whenever asked. And last, but certainly not least, a heartfelt thank you to Johannes Endres who remained calm when people talked out loud during the quiz, who had me be his TA over and over, and who went above and beyond in his role here. iv Dedication: For Anita, Aubrey, Fiona, George, Larry, Lillian, Myrna, Noël and Paul. v Table of Contents Excerpt from Pentimento by Lillian Hellman ......................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 2 Chapter 1: Biographical Information for Dureau and Bellocq .......................... 18 Table 1 ...................................................................................................... 32 Excerpt from One Arm by Tennessee Williams.................................................... 34 Chapter 2: Colonial Foundations of Libertine Tolerance in New Orleans, LA .. -

Afrikan Revolutionary Assassinated!!!

VOLUME·1 1 NUMBERII FEBRUARI1973 15 CENTS AFRIKANREVOLUTIONARY ASSASSINATED!!! concrete PanAfrikanism linking The news of the assassination of Afrikans in the West with Afrikans on Brother Amilcar Cabral should come the continent, so Brother Cabral, as a shattering shock to all Afrikan when he began to move past the people and all people who are seriously involved in the Liberation of theories of PanAfrikanism into the Afrikan people as well as the concrete establishment of Liberation of all oppressed people all PanAfrikanist ties, was also mur over the world. Brother Cabral, dered . Secretary-General of (PAIGC) We accuse the American govern Afrikan Party for the Independence of ment with active , decisive support of Guinea -Bissau and Cape Verde this blow against Afrikan Liberation. Islands, was a leader in the struggle It's no secret that Hitler-Nixon and of World Afrikan Liberation, a true his fascist advisors not only support PanAfrikanist whose intellectual Portuguese colonialism in the United understanding of revolution was Nations, but with the tax money of matched only by his actual com American citizens, and in a country mittment as leader of an Afrikan Amilcar Cabral with at least 30 million Afrikans living revolutionary party engaged in ar colonialism to murder him. Brother that the National Assembly of Guinea within it, it's shocking that white med struggle . Cabral's thrust at linking up the Bissa u had been formed in December, racists should continue to act as if President Toure has already ac struggle between Afrikans on the that Secretary-Gene ral Cabral had there were no Afrikans living in cused the forces of Portuguese continent and Afrikans of the Western announced plans of Guinea-Bissa u to America. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: SLAVE SHIPS, SHAMROCKS, AND SHACKLES: TRANSATLANTIC CONNECTIONS IN BLACK AMERICAN AND NORTHERN IRISH WOMEN’S REVOLUTIONARY AUTO/BIOGRAPHICAL WRITING, 1960S-1990S Amy L. Washburn, Doctor of Philosophy, 2010 Dissertation directed by: Professor Deborah S. Rosenfelt Department of Women’s Studies This dissertation explores revolutionary women’s contributions to the anti-colonial civil rights movements of the United States and Northern Ireland from the late 1960s to the late 1990s. I connect the work of Black American and Northern Irish revolutionary women leaders/writers involved in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Black Panther Party (BPP), Black Liberation Army (BLA), the Republic for New Afrika (RNA), the Soledad Brothers’ Defense Committee, the Communist Party- USA (Che Lumumba Club), the Jericho Movement, People’s Democracy (PD), the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP), the National H-Block/ Armagh Committee, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), Women Against Imperialism (WAI), and/or Sinn Féin (SF), among others by examining their leadership roles, individual voices, and cultural productions. This project analyses political communiqués/ petitions, news coverage, prison files, personal letters, poetry and short prose, and memoirs of revolutionary Black American and Northern Irish women, all of whom were targeted, arrested, and imprisoned for their political activities. I highlight the personal correspondence, auto/biographical narratives, and poetry of the following key leaders/writers: Angela Y. Davis and Bernadette Devlin McAliskey; Assata Shakur and Margaretta D’Arcy; Ericka Huggins and Roseleen Walsh; Afeni Shakur-Davis, Joan Bird, Safiya Bukhari, and Martina Anderson, Ella O’Dwyer, and Mairéad Farrell. -

RG 68 Master Calendar

RG 68 MASTER CALENDAR Louisiana State Museum Historical Center Archives May 2012 Date Description 1387, 1517, 1525 Legal document in French, Xerox copy (1966.011.1-.3) 1584, October 20 Letter, from Henry IV, King of France, to Francois de Roaldes (07454) 1640, August 12 1682 copy of a 1640 Marriage contract between Louis Le Brect and Antoinette Lefebre (2010.019.00001.1-.2) 1648, January 23 Act of sale between Mayre Grignonneau Piqueret and Charles le Boeteux (2010.019.00002.1-.2) 1680, February 21 Photostat, Baptismal certificate of Jean Baptoste, son of Charles le Moyne and marriage contract of Charles le Moyne and Catherine Primot (2010.019.00003 a-b) 1694 Reprint (engraving), frontspiece, an Almanack by John Tulley (2010.019.00004) c. 1700-1705 Diary of Louisiana in French (2010.019.00005 a-b) c. 1700 Letter in French from Philadelphia, bad condition (2010.019.00006) 1711, October 18 Document, Spanish, bound, typescript, hand-illustrated manuscript of the bestowing of a title of nobility by Charles II of Spain, motto on Coat of Arms of King of Spain, Philippe V, Corella (09390.1) 1711, October 18 Typescript copy of royal ordinance, bestows the title of Marquis deVillaherman deAlfrado on Dr. Don Geronina deSoria Velazquez, his heirs and successors as decreed by King Phillip 5th, Spain (19390.2) 1714, January 15 English translation of a letter written at Pensacola by M. Le Maitre, a missionary in the country (2010.019.00007.1-.29) 1714 Document, translated into Spanish from French, regarding the genealogy of the John Douglas de Schott family (2010.019.00008 a-b) 1719, December 29 Document, handwritten copy, Concession of St. -

Black News Table of Contents

Black News Table of Contents Boxes 7 through 11 of the Civil Rights in Brooklyn Collection Call Number: BC 0023 Brooklyn Public Library – Brooklyn Collection Box 7: Location MR 1.5 Vol. 1 No. 1, October 1969 Willie Thompson “Black News “of Bedford Stuyvesant The Uhuru Academy Explanation Of the So-called Generation Enemies of the Black Communities Gap Radical Approach toward low-income housing Vol. 1 No. 4, November 15, 1969 The Black study circle Christmas Nigger “The Beast” ( a poem) Harlem’s demand for self-determination Make it, Buy it, or Take it Black Study Circle Black soul plays Understanding Enemies of the Black community All out race war in U.S. Marines…1970 The Black Ass Kickin' Brigade The Healer Forced out of their Home Modern Cities and Nigger incompetence “One Bloody Night” What’s on? No School! protest Bobby Seale From Sister to Sister Are policemen really pigs or worse? Vol. 1 No. 2, October 1969 Liberty House Ocean Hill Brownsville –Revisited-1969- Keep the grapevine buzzin Less Campbell Lindsay owes his body and soul Seminar for Black women Enemies of the Black Communities Black people spend $35 billion annually “The Death Dance” (a poem) Post Revolution thought ( a poem) Community control of the land “I Love America” (a poem) Vol. 1 No. 5 December 1, 1969 Another Black patriot doomed by the pig Rapping on Racists America is so beautiful in the Autumn The arrogance of Model Cities Ho Chi Minh – The man and his plan The soap-opera syndrome “The Needle”(a poem) His Master’s voice A Black father’s one man crusade against Vol. -

Black Women's Fiction and the Abject In

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses July 2018 WRITING NEW BOUNDARIES FOR THE LAW: BLACK WOMEN’S FICTION AND THE ABJECT IN PSYCHOANALYSIS Angelique Warner U Massachussetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Warner, Angelique, "WRITING NEW BOUNDARIES FOR THE LAW: BLACK WOMEN’S FICTION AND THE ABJECT IN PSYCHOANALYSIS" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1303. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1303 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WRITING NEW BOUNDARIES FOR THE LAW: BLACK WOMEN’S FICTION AND THE ABJECT IN PSYCHOANALYSIS A Dissertation Presented by ANGELIQUE WARNER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies © Angelique Warner 2018 All Rights Reserved WRITING NEW BOUNDARIES FOR THE LAW: BLACK WOMEN’s FICTION AND THE ABJECT IN PSYCHOANALYSIS A Dissertation Presented by ANGELIQUE WARNER Approved as to style and content by: James Smethurst, Chair Manisha Sinha, Member TreAndrea Russworm, Member Priscilla Page, Member Amilcar Shabazz, Department Head W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies DEDICATION For Octavia Butler ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, James Smethurst, for his years of encouragement and his expertise in an area of literature that is so important to me. -

1 Record Group 1 Judicial Records of the French

RECORD GROUP 1 JUDICIAL RECORDS OF THE FRENCH SUPERIOR COUNCIL Acc. #'s 1848, 1867 1714-1769, n.d. 108 ln. ft (216 boxes); 8 oversize boxes These criminal and civil records, which comprise the heart of the museum’s manuscript collection, are an invaluable source for researching Louisiana’s colonial history. They record the social, political and economic lives of rich and poor, female and male, slave and free, African, Native, European and American colonials. Although the majority of the cases deal with attempts by creditors to recover unpaid debts, the colonial collection includes many successions. These documents often contain a wealth of biographical information concerning Louisiana’s colonial inhabitants. Estate inventories, records of commercial transactions, correspondence and copies of wills, marriage contracts and baptismal, marriage and burial records may be included in a succession document. The colonial document collection includes petitions by slaves requesting manumission, applications by merchants for licenses to conduct business, requests by ship captains for absolution from responsibility for cargo lost at sea, and requests by traders for permission to conduct business in Europe, the West Indies and British colonies in North America **************************************************************************** RECORD GROUP 2 SPANISH JUDICIAL RECORDS Acc. # 1849.1; 1867; 7243 Acc. # 1849.2 = playing cards, 17790402202 Acc. # 1849.3 = 1799060301 1769-1803 190.5 ln. ft (381 boxes); 2 oversize boxes Like the judicial records from the French period, but with more details given, the Spanish records show the life of all of the colony. In addition, during the Spanish period many slaves of Indian 1 ancestry petitioned government authorities for their freedom. -

A History of Theatre in New Orleans from 1925 to 1935. Melvin Howard Berry Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 A History of Theatre in New Orleans From 1925 to 1935. Melvin Howard Berry Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Berry, Melvin Howard, "A History of Theatre in New Orleans From 1925 to 1935." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2446. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2446 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Street Renaming Commission

NEW ORLEANS CITY COUNCIL STREET RENAMING COMMISSION FINAL REPORT March 1, 2021 FINAL REPORT MARCH 1, 2021 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary 02 Letter from the Chair 04 Introduction 05 New Orleans City Council Approved Motion 06 M-20-170 and Commission Charge City Council Streets Renaming Commission 07 Working Group Policy Impacting Naming and Removal of 10 Assets Assets: Defined and Prioritized 13 Summary of Engagement Activities (Voices 14 from New Orleans Residents) City Council Street Renaming Commission 22 Final Recommendations Appendix / Reference Materials 38 Commission Meeting Public Comments 42 Website Public Comments 166 NEW ORLEANS CITY COUNCIL STREET RENAMING COMMISSION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On June 18, 2020, the New Orleans City Council unanimously voted to establish the City Council Street Renaming Commission (CCSRC) as an advisory committee to run a public process for making recommendations to rename streets, parks, and places in New Orleans that honor white supremacists. The CCSRC is composed of nine total members, with one appointed by each Councilmember with a formal or informal background of the history and geography of New Orleans. Mayor LaToya Cantrell and the City Planning Commission appointed the remaining two members. The Commission was charged with several key responsibilities, which included conducting a thorough research and public engagement process to develop a comprehensive set of renaming recommendations for streets, parks, and places across the city. In the course of auditing the list of City streets beyond those initially identified by the New Orleans Public Library, the Commission consulted a panel of experts to provide an additional set of names, which was used to formulate the recommendations listed in this report. -

Ernest N. “Dutch” and His Son Marc, Each Had a Lasting Legacy in New Orleans — Though Both Legacies Are Marked by Dissent and Controversy

NEW ORLEANS From Bienville to Bourbon Street to bounce. 300 moments that make New Orleans unique. WHAT HAPPENED Ernest “Dutch” 1718 ~ 2018 Morial became the city’s first black mayor 300 on May 2, 1978. TRICENTENNIAL The Morials — Ernest N. “Dutch” and his son Marc, each had a lasting legacy in New Orleans — though both legacies are marked by dissent and controversy. “Dutch” Morial who succeeded him as mayor. He refused became New to bow to demands in a police strike in 1979, Orleans’ first which effectively canceled Mardi Gras. black mayor in “I think he will also be remembered for 1978 and served his tenacity and pugnaciousness. He was THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE two terms. He certainly controversial, and I think will THE NEW ORLEANS HISTORIC COLLECTION was also the first be remembered for that also, and very African-Amer- fondly by some,” said former Mayor Moon The second term of Marc Morial, shown in ican graduate Landrieu after Dutch died in 1989. 1998, ended in 2002 and was tainted by an in- vestigation into his administration’s contracts. from Louisiana Marc Morial also Both Dutch and Marc Morial State Univer- clashed with the City tried to get the public to agree sity’s law school; Council as he worked to to lift term limits so they could the first black balance the city’s budget, run for a third term. assistant U.S. at- and led efforts to create LOYOLA UNIVERSITY Lolis Elie, Rev. torney in Louisiana; the first black Louisiana an ethics board and in- THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE A.L.