Advancing Textile Craft Through Innovation: the Influence and Legacy of Jack Lenor Larsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Metal and Jewelry Arts Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 29:2 — Fall 2017" (2017). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 80. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/80 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 29. NUMBER 2. FALL 2017 Photo Credit: Tourism Vancouver See story on page 6 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of Communications) Designer: Meredith Affleck Vita Plume Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (TSA General Manager) President [email protected] Editorial Assistance: Natasha Thoreson and Sarah Molina Lisa Kriner Vice President/President Elect Our Mission [email protected] Roxane Shaughnessy The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for Past President the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, [email protected] political, social, and technical perspectives. Established in 1987, TSA is governed by a Board of Directors from museums and universities in North America. -

Keynote Addressâ•Flsummary Notes

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2004 Keynote Address—Summary Notes Jack Lenor Larsen Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Larsen, Jack Lenor, "Keynote Address—Summary Notes" (2004). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 494. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/494 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Keynote Address—Summary Notes San Francisco Bay as the Fountainhead and Wellspring Jack Lenor Larsen Jack Lenor Larsen led off the 9th Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America in Oakland, California, with a plenary session directed to TSA members and conference participants. He congratulated us, even while proposing a larger and more inclusive vision of our field, and exhorting us to a more comprehensive approach to fiber. His plenary remarks were spoken extemporaneously from notes and not recorded. We recognize that their inestimable value deserves to be shared more broadly; Jack has kindly provided us with his rough notes for this keynote address. The breadth of his vision, and his insightful comments regarding fiber and art, are worthy of thoughtful consideration by all who concern themselves with human creativity. On the Textile Society of America Larsen proffered congratulations on the Textile Society of America, now fifteen years old. -

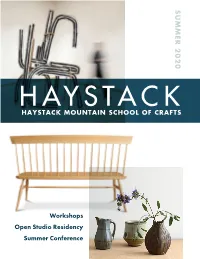

Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference

SUMMER 2020 HAYSTACK MOUNTAIN SCHOOL OF CRAFTS Workshops Open Studio Residency Summer Conference Schedule at a Glance 4 SUMMER 2020 Life at Haystack 6 Open Studio Residency 8 Session One 10 Welcome Session Two This year will mark the 70th anniversary of the 14 Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. The decision to start a school is a radical idea in and Session Three 18 of itself, and is also an act of profound generosity, which hinges on the belief that there exists something Session Four 22 so important it needs to be shared with others. When Haystack was founded in 1950, it was truly an experiment in education and community, with no News & Updates 26 permanent faculty or full-time students, a school that awarded no certificates or degrees. And while the school has grown in ways that could never have been Session Five 28 imagined, the core of our work and the ideas we adhere to have stayed very much the same. Session Six 32 You will notice that our long-running summer conference will take a pause this season, but please know that it will return again in 2021. In lieu of a Summer Workshop 36 public conference, this time will be used to hold Information a symposium for the Haystack board and staff, focusing on equity and racial justice. We believe this is vital Summer Workshop work for us to be involved with and hope it can help 39 make us a more inclusive organization while Application broadening access to the field. As we have looked back to the founding years of the Fellowships 41 school, together we are writing the next chapter in & Scholarships Haystack’s history. -

Working Checklist 00

Taking a Thread for a Walk The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 21, 2019 - June 01, 2020 WORKING CHECKLIST 00 - Introduction ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Untitled from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 17 3/4 × 13 3/4" (45.1 × 34.9 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 74 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Study for Nylon Rug from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 20 5/8 × 15 1/8" (52.4 × 38.4 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 75 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) With Verticals from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 19 3/8 × 14 1/4" (49.2 × 36.2 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 73 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Orchestra III from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 26 5/8 × 18 7/8" (67.6 × 47.9 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

ORNAMENT 30.3.2007 30.3 TOC 2.FIN 3/18/07 12:39 PM Page 2

30.3 COVERs 3/18/07 2:03 PM Page 1 992-994_30.3_ADS 3/18/07 1:16 PM Page 992 01-011_30.3_ADS 3/16/07 5:18 PM Page 1 JACQUES CARCANAGUES, INC. LEEKAN DESIGNS 21 Greene Street New York, NY 10013 BEADS AND ASIAN FOLKART Jewelry, Textiles, Clothing and Baskets Furniture, Religious and Domestic Artifacts from more than twenty countries. WHOLESALE Retail Gallery 11:30 AM-7:00 PM every day & RETAIL (212) 925-8110 (212) 925-8112 fax Wholesale Showroom by appointment only 93 MERCER STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10012 (212) 431-3116 (212) 274-8780 fax 212.226.7226 fax: 212.226.3419 [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] WHOLESALE CATALOG $5 & TAX I.D. Warehouse 1761 Walnut Street El Cerrito, CA 94530 Office 510.965.9956 Pema & Thupten Fax 510.965.9937 By appointment only Cell 510.812.4241 Call 510.812.4241 [email protected] www.tibetanbeads.com 1 ORNAMENT 30.3.2007 30.3 TOC 2.FIN 3/18/07 12:39 PM Page 2 volumecontents 30 no. 3 Ornament features 34 2007 smithsonian craft show by Carl Little 38 candiss cole. Reaching for the Exceptional by Leslie Clark 42 yazzie johnson and gail bird. Aesthetic Companions by Diana Pardue 48 Biba Schutz 48 biba schutz. Haunting Beauties by Robin Updike Candiss Cole 38 52 mariska karasz. Modern Threads by Ashley Callahan 56 tutankhamun’s beadwork by Jolanda Bos-Seldenthuis 60 carol sauvion’s craft in america by Carolyn L.E. Benesh 64 kristina logan. Master Class in Glass Beadmaking by Jill DeDominicis Cover: BUTTERFLY PINS by Yazzie Johnson and Gail Bir d, from top to bottom: Morenci tur quoise and tufa-cast eighteen karat gold, 7.0 centimeters wide, 2005; Morenci turquoise, lapis, azurite and fourteen karat gold, 5.1 centimeters wide, 1987; Morenci turquoise and tufa-cast eighteen karat gold, 5.7 centimeters wide, 2005; Tyrone turquoise, coral and tufa- cast eighteen karat gold, 7.6 centimeters wide, 2006; Laguna agates and silver, 7.6 centimeters wide, 1986. -

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian American Art Museum Chronological List of Past Exhibitions and Installations on View at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery 1958-2016 ■ = EXHIBITION CATALOGUE OR CHECKLIST PUBLISHED R = RENWICK GALLERY INSTALLATION/EXHIBITION May 1921 xx1 American Portraits (WWI) ■ 2/23/58 - 3/16/58 x1 Paul Manship 7/24/64 - 8/13/64 1 Fourth All-Army Art Exhibition 7/25/64 - 8/13/64 2 Potomac Appalachian Trail Club 8/22/64 - 9/10/64 3 Sixth Biennial Creative Crafts Exhibition 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 4 Ancient Rock Paintings and Exhibitions 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 5 Capital Area Art Exhibition - Landscape Club 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 6 71st Annual Exhibition Society of Washington Artists 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 7 Wildlife Paintings of Basil Ede 11/14/64 - 12/3/64 8 Watercolors by “Pop” Hart 11/14/64 - 12/13/64 9 One Hundred Books from Finland 12/5/64 - 1/5/65 10 Vases from the Etruscan Cemetery at Cerveteri 12/13/64 - 1/3/65 11 27th Annual, American Art League 1/9/64 - 1/28/65 12 Operation Palette II - The Navy Today 2/9/65 - 2/22/65 13 Swedish Folk Art 2/28/65 - 3/21/65 14 The Dead Sea Scrolls of Japan 3/8/65 - 4/5/65 15 Danish Abstract Art 4/28/65 - 5/16/65 16 Medieval Frescoes from Yugoslavia ■ 5/28/65 - 7/5/65 17 Stuart Davis Memorial Exhibition 6/5/65 - 7/5/65 18 “Draw, Cut, Scratch, Etch -- Print!” 6/5/65 - 6/27/65 19 Mother and Child in Modern Art ■ 7/19/65 - 9/19/65 20 George Catlin’s Indian Gallery 7/24/65 - 8/15/65 21 Treasures from the Plantin-Moretus Museum Page 1 of 28 9/4/65 - 9/25/65 22 American Prints of the Sixties 9/11/65 - 1/17/65 23 The Preservation of Abu Simbel 10/14/65 - 11/14/65 24 Romanian (?) Tapestries ■ 12/2/65 - 1/9/66 25 Roots of Abstract Art in America 1910 - 1930 ■ 1/27/66 - 3/6/66 26 U.S. -

At Long Last Love Press Release

At Long Last Love: Fiber Sculpture Gets Its Due October 2014 It looks as if 2014 will be the year that contemporary fiber art finally gets the recognition and respect it deserves. For us, it kicked off at the Whitney Biennial in May which gave pride of place to Sheila Hicks’ massive cascade, Pillar of Inquiry/Supple Column. Last month saw the opening of the influential Thread Lines, at The Drawing Center in New York featuring work by 16 artists who sew, stitch and weave. Now at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the development of ab- straction and dimensionality in fiber art from the mid-twentieth centu- ry through to the present is examined in Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present from October 1st through January 4, 2015. The exhibition features 50 works by 34 artists, who crisscross generations, nationalities, processes and aesthetics. It is accompanied by an attractive companion volume, Fiber: Sculpture 1960-present available at browngrotta.com. There are some standout works in the exhibition — we were thrilled Fiber: Sculpture 1960 — present opening photo by Tom Grotta to see Naomi Kobayashi’s Ito wa Ito (1980) and Elsi Giauque’s Spatial Element (1989), on loan from European museums, in person after ad- miring them in photographs. Anne Wilson’s Blonde is exceptional and Ritzi Jacobi and Françoise Grossen are represented by strong works, too, White Exotica (1978, created with Peter Jacobi) and Inchworm, respectively. Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present aims to create a sculp- tural dialogue, an art dialogue — not one about craft, ICA Mannion Family Senior Curator Jenelle Porter explained in an opening-night conversation with Glenn Adamson, Director, Museum of Arts and Design. -

Oral History Interview with Anne Wilson, 2012 July 6-7

Oral history interview with Anne Wilson, 2012 July 6-7 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Transcription of this oral history interview was made possible by a grant from the Smithsonian Women's Committee. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Anne Wilson on July 6 and 7, 2012. The interview took place in the artist's studio in Evanston, Illinois, and was conducted by Mija Riedel for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Anne Wilson and Mija Riedel have reviewed the transcript. Their heavy corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview MIJA RIEDEL: This is Mija Riedel with Anne Wilson at the artist's studio in Evanston, Illinois, on July 6, 2012, for the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art. This is disc number one. So, Anne, let's just take care of some of the early biographical information first. You were born in Detroit in 1949? ANNE WILSON: I was. MS. RIEDEL: Okay. And would you tell me your parents' names? MS. -

Fiberartoral00lakyrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Gyongy Laky FIBER ART: VISUAL THINKING AND THE INTELLIGENT HAND With an Introduction by Kenneth R. Trapp Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1998-1999 Copyright 2003 by The Regents of the University of California has been Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Gyongy Laky, dated October 21, 1999. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Sheila Hicks CV

SHEILA HICKS Born Hastings, Nebraska 1934 EDUCATION 1959 MFA, Yale University, New Haven, CT 1957 BFA, Yale University, New Haven, CT SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Sheila Hicks: Life Lines, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, February 6 – April 30, 2018. Sheila Hicks: Send Dessus Dessous, Domaine de Chaumont-sur Loire Centre d’Arts et de Nature, Chaumont-sur Loire, France, March 30, 2018 – February 2, 2019. Down Side Up, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY, May 24 – July 6, 2018. 2017 Sheila Hicks: Glossolalia, Domaine de Chaumont-sur Loire Centre d’Arts et de Nature, Chaumont-sur Loire, France, April 1 – November 5, 2017. Sheila Hicks: Hilos Libres. El Textil y Sus Raíces Preshispánicas, 1954-2017, Museo Amparo, Puebla, Mexico, November 4, 2017 – April 2, 2018. Sheila Hicks: Stones of Piece, Alison Jaques Gallery, London, England, October 4 – November 11, 2017. Sheila Hicks: Hop, Skip, Jump, and Fly: Escape from Gravity, High Line, New York, New York, June 2017 – March 2018. Sheila Hicks: Au-delà, Museé d’Arte Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France, December 1 – May 20, 2018. 2016 Si j’étais de laine, m’accepteriez-vous?, galerie frank elbaz, Paris, France, September 10 – October 15, 2016. Apprentissages, Festival d’Automne, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, France, September 13 – October 2, 2016; Nanterre-Amandiers, Paris, France, December 9 – 17, 2016. Sheila Hicks: Material Voices, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, June 5 – September 4, 2016; travels to: Textile Museum of Canada, Toronto, Canada, October 6, 2016 – February 5, 2017. Sheila Hicks: Why Not?, Textiel Museum, Tilburg, The Netherlands, March 5 – June 5, 2016. -

Growing up in Seattle, Jack Lenor Larsen's Initiation to Visual Culture

JACK LENOR LARSEN Growing up in and around Seattle, Jack Lenor Larsen’s initiation to visual culture was colored by the Asian aesthetic by which much of the Pacific Northwest is characterized. Set against Puget Sound and a background of volcanic peaks, glacial inlets and pearly light, the native palette there is one of muted earth tones and misty blues and grays. Last month, the renowned textile designer, author, insatiable collector and founder of LongHouse Reserve in East Hampton sat down to reflect on raking pine needles, spinning yarn and the qualities of a simple life. “Weaving is like architecture,” said Mr. Larsen. “The focus is on material; shade and shadow; of texture. And being useful – purposeful.” He paused to consider one of the intricate Thai baskets arranged on the table between us. Reaching out, he moved it to the left about a quarter of an inch. “Therefore it’s logical. It presents limitations that act as guideposts. You think about what has to be achieved and it builds itself for you, whereas a blank canvas is clueless.” One could posit that in the beginning, the 16 acre parcel on which LongHouse Reserve’s gardens, sculpture installations and 13,000 square foot house now thrive was just such a blank canvas, albeit of staggering proportions. “It did have some challenges,” he conceded. Founded in 1991, LongHouse Reserve is just one of many remarkable ventures in this weaver’s eighty some years. In fact, it’s hard to believe Jack Lenor Larsen has squeezed so much into one lifetime. From boardroom to bedroom, Mr.