What Is Evidence-Based About Myofascial Chains: a Systematic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tibialis Posterior Tendon Transfer Corrects the Foot Drop Component

456 COPYRIGHT Ó 2014 BY THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY,INCORPORATED Tibialis Posterior Tendon Transfer Corrects the Foot DropComponentofCavovarusFootDeformity in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease T. Dreher, MD, S.I. Wolf, PhD, D. Heitzmann, MSc, C. Fremd, M.C. Klotz, MD, and W. Wenz, MD Investigation performed at the Division for Paediatric Orthopaedics and Foot Surgery, Department for Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery, Heidelberg University Clinics, Heidelberg, Germany Background: The foot drop component of cavovarus foot deformity in patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is commonly treated by tendon transfer to provide substitute foot dorsiflexion or by tenodesis to prevent the foot from dropping. Our goals were to use three-dimensional foot analysis to evaluate the outcome of tibialis posterior tendon transfer to the dorsum of the foot and to investigate whether the transfer works as an active substitution or as a tenodesis. Methods: We prospectively studied fourteen patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and cavovarus foot deformity in whom twenty-three feet were treated with tibialis posterior tendon transfer to correct the foot drop component as part of a foot deformity correction procedure. Five patients underwent unilateral treatment and nine underwent bilateral treatment; only one foot was analyzed in each of the latter patients. Standardized clinical examinations and three-dimensional gait analysis with a special foot model (Heidelberg Foot Measurement Method) were performed before and at a mean of 28.8 months after surgery. Results: The three-dimensional gait analysis revealed significant increases in tibiotalar and foot-tibia dorsiflexion during the swing phase after surgery. These increases were accompanied by a significant reduction in maximum plantar flexion at the stance-swing transition but without a reduction in active range of motion. -

The Anatomy of the Posterolateral Aspect of the Rabbit Knee

Journal of Orthopaedic Research ELSEVIER Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2 I (2003) 723-729 www.elsevier.com/locate/orthres The anatomy of the posterolateral aspect of the rabbit knee Joshua A. Crum, Robert F. LaPrade *, Fred A. Wentorf Dc~~ur/niiviiof Orthopuer/ic Surgery. Unicrrsity o/ Minnesotu. MMC 492, 420 Dcluwur-c Si. S. E., Minnwpoli,s, MN 55455, tiSA Accepted 14 November 2002 Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine the anatomy of the posterolateral aspect of the rabbit knee to serve as a basis for future in vitro and in vivo posterolateral knee biomechanical and injury studies. Twelve nonpaired fresh-frozen New Zealand white rabbit knees were dissected to determine the anatomy of the posterolateral corner. The following main structures were consistently identified in the rabbit posterolateral knee: the gastrocnemius muscles, biceps femoris muscle, popliteus muscle and tendon, fibular collateral ligament, posterior capsule, ligament of Wrisberg, and posterior meniscotibial ligament. The fibular collateral ligament was within the joint capsule and attached to the femur at the lateral epi- condyle and to the fibula at the midportion of the fibular head. The popliteus muscle attached to the medial edge of the posterior tibia and ascended proximally to give rise to the popliteus tendon, which inserted on the proximal aspect of the popliteal sulcus just anterior to the fibular collateral ligament. The biceps femoris had no attachment to the fibula and attached to the anterior com- partment fascia of the leg. This study increased our understanding of these structures and their relationships to comparative anatomy in the human knee. -

Plantar Fascia-Specific Stretching Program for Plantar Fasciitis

Plantar Fascia-Specific Stretching Program For Plantar Fasciitis Plantar Fascia Stretching Exercise 1. Cross your affected leg over your other leg. 2. Using the hand on your affected side, take hold of your affected foot and pull your toes back towards shin. This creates tension/stretch in the arch of the foot/plantar fascia. 3. Check for the appropriate stretch position by gently rubbing the thumb of your unaffected side left to right over the arch of the affected foot. The plantar fascia should feel firm, like a guitar string. 4. Hold the stretch for a count of 10. A set is 10 repetitions. 5. Perform at least 3 sets of stretches per day. You cannot perform the stretch too often. The most important times to stretch are before taking the first step in the morning and before standing after a period of prolonged sitting. Plantar Fascia Stretching Exercise 1 2 3 4 URMC Orthopaedics º 4901 Lac de Ville Boulevard º Building D º Rochester, NY 14618 º 585-275-5321 www.ortho.urmc.edu Over, Please Anti-inflammatory Medicine Anti-inflammatory medicine will help decrease the inflammation in the arch and heel of your foot. These include: Advil®, Motrin®, Ibuprofen, and Aleve®. 1. Use the medication as directed on the package. If you tolerate it well, take it daily for 2 weeks then discontinue for 1 week. If symptoms worsen or return, then resume medicine for 2 weeks, then stop. 2. You should eat when taking these medications, as they can be hard on your stomach. Arch Support 1. -

Chronic Tibialis Anterior Tendon Tear Treated with an Achilles Tendon Allograft Technique

n tips & techniques Section Editor: Steven F. Harwin, MD Chronic Tibialis Anterior Tendon Tear Treated With an Achilles Tendon Allograft Technique Ezequiel Palmanovich, MD; Yaron S. Brin, MD; Lior Laver, MD; Dror Ben David, MD; Sabri Massrawe, MD; Meir Nyska, MD; Iftach Hetsroni, MD tus,16,17 rheumatoid arthritis,17 erative tibialis anterior tendon Abstract: Tibialis anterior tendon tear is an uncommon in- psoriasis,18 and deposition of was diagnosed clinically and jury. Nontraumatic or degenerative tears are usually seen gout tophi19,20 also have been confirmed by ultrasound. in the avascular zone of the tendon. Treatment can be con- reported to be associated with After 3 months of phys- servative or surgical. Conservative treatment is adequate tendon ruptures. In older pa- iotherapy treatment without for low-demand older patients. For active patients, surgical tients and in partial tears, non- improvement, surgical treat- treatment can be challenging for the surgeon because after operative treatment has been ment was recommended. The debridement of degenerative tissue, a gap may be formed described.8,21 patient’s American Orthopae- that can make side-to-side suture impossible. The authors Surgical techniques de- dic Foot and Ankle Society present allograft Achilles tendon insertion for reconstruc- scribed in the literature in- (AOFAS)22 score was 23 and tion of chronic degenerative tears. Using Achilles tendon al- clude direct side-to-side his Foot and Ankle Disabil- lograft has the advantage of bone-to-bone fixation, allowing repair and interposition of ity Index (FADI)23 score was rapid incorporation and earlier full weight bearing. autogenous tendon graft for 34.6 preoperatively. -

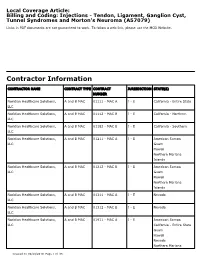

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. -

Treatment of Spastic Foot Deformities

TREATMENT OF SPASTIC FOOT DEFORMITIES penn neuro-orthopaedics service Table of Contents OVERVIEW Severe loss of movement is often the result of neurological disorders, Overview .............................................................. 1 such as stroke or brain injury. As a result, ordinary daily activities Treatment ............................................................. 2 such as walking, eating and dressing can be difficult and sometimes impossible to accomplish. Procedures ........................................................... 4 The Penn Neuro-Orthopaedics Service assists patients with Achilles Tendon Lengthening .........................................4 orthopaedic problems caused by certain neurologic disorders. Our Toe Flexor Releases .....................................................5 team successfully treats a wide range of problems affecting the limbs including foot deformities and walking problems due to abnormal Toe Flexor Transfer .......................................................6 postures of the foot. Split Anterior Tibialis Tendon Transfer (SPLATT) ...............7 This booklet focuses on the treatment of spastic foot deformities The Extensor Tendon of the Big Toe (EHL) .......................8 under the supervision of Keith Baldwin, MD, MSPT, MPH. Lengthening the Tibialis Posterior Tendon .......................9 Care After Surgery .................................................10 Notes ..................................................................12 Pre-operative right foot. Post-operative -

Advice and Exercises for Patients with Plantar Fasciitis

Advice and exercises for patients with plantar fasciitis This leaflet provides management advice and exercises for people diagnosed with plantar fasciitis, a condition causing pain in the heel, sole and /or arch of the foot. Structures of the foot The plantar fascia is a sheet or broad band of fibrous tissue that runs along the bottom of the foot. This tissue connects the heel to the base of the toes. Under normal circumstances, the plantar fascia supports the arch of the foot and acts as a shock absorbing “bow string” within the arch of the foot. With weight bearing, the foot flattens and the plantar fascia stretches, then springing you forward ready for the next step. While walking, the stresses placed on the foot can be one and a quarter times your body weight (this increases to two and three quarter times your body weight when running). Unsurprisingly then, that heel pain is common. If tension on this “bowstring” becomes too great, irritation or inflammation can occur causing pain. What is plantar fasciitis? Plantar fasciitis is a relatively common foot problem affecting up to 10-15% of the population. It can occur at any age. It is sometimes known as “policeman’s heel”. When placed under too much stress due to abnormal loading, the plantar fascia stretches causing micro tearing and degeneration of the tissue. It can lead to pain in the heel, across the sole of the foot and sometimes into the arch area of the foot too. These micro tears repair with scar tissue, which is less flexible than the fascia and can cause the problem to persist for many months. -

Traumatic Tear of Tibialis Anterior During a Gaelic Football Game: a Case Report M Constantinou, a Wilson

1of3 Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.2003.007625 on 23 November 2004. Downloaded from CASE REPORT Traumatic tear of tibialis anterior during a Gaelic football game: a case report M Constantinou, A Wilson ............................................................................................................................... Br J Sports Med 2004;38:e30 (http://www.bjsportmed.com/cgi/content/full/38/6/e30) were considered irrefutable evidence of a rupture, so Reports of traumatic injury to the anterior lower leg muscles operative management was undertaken one week after the are scarce, with only a handful of reports of traumatic injury injury. to the tibialis anterior. A database search of Medline, Cinhal, Surgery revealed a complete traumatic tear of tibialis and Sports Discus only revealed three such cases, and they anterior at the musculotendinous junction. The tendon had did not result from a direct sporting injury. This report ruptured directly from the muscle belly, which had also documents the case of a traumatic rupture of tibialis anterior sustained some muscle fibre damage (fig 1). The tendon was muscle in a young female Gaelic football player. It details the subsequently sutured back to the muscle belly using surgical repair and management of tibialis anterior muscle absorbable interrupted sutures. and the physiotherapy rehabilitation to full function. Post-surgical management consisted of an initial period of six weeks non-weight bearing and immobilisation in a short leg fibreglass cast, followed by four weeks in an ankle-foot orthosis with partial weight bearing. Active physiotherapy raumatic injuries to the lower limb are often associated rehabilitation was begun 10 weeks after surgery. The with contact team sports. -

Plantar Fasciitis Exercises

Accurate Clinic 2401 Veterans Memorial Blvd. Suite16 Kenner, LA 70062 - 4799 Phone: 504.472.6130 Fax: 504.472.6128 www.AccurateClinic.com Plantar Fasciitis Exercise Getting the right plantar fasciitis exercise is imperative to ensure the injury doesn’t continue to affect performance. If not given the attention it needs, plantar fasciitis can flair up long after an athlete thinks they’ve recovered and badly damage training plans and competition aspirations. What is plantar fascia? Plantar fascia is a thick, fibrous band of connective tissue which originates at the heel bone and runs along the bottom of the foot in a fan-like manner, attaching to the base of each of the toes. A rather tough, resilient structure, the plantar fascia takes on a number of critical functions during running and walking. Although the fascia is invested with countless sturdy 'cables' of connective tissue called collagen fibres, it is certainly not immune to injury. In fact, about 5 to 10 per cent of all running injuries are inflammations of the fascia, an incidence rate which in the United States would produce about a million cases of plantar fasciitis per year, just among runners and joggers. Basketball players, tennis players, volleyballers, step-aerobics participants, and dancers are also prone to plantar problems, as are non-athletic people who spend a lot of time on their feet or suddenly become active after a long period of lethargy. Why does the fascia flare up? Although it is a fairly rugged structure, the plantar fascia is not very receptive to stretching, and yet stretching occurs in the fascia nearly every time the foot hits the ground. -

Axis Scientific 9-Part Foot with Muscles, Ligaments, Nerves & Arteries A-105857

Axis Scientific 9-Part Foot with Muscles, Ligaments, Nerves & Arteries A-105857 DORSAL VIEW LATERAL VIEW 53. Superficial Fibular (Peroneal) Nerve 71. Fibula 13. Fibularis (Peroneus) Longus Tendon 17. Anterior Talofibular Ligament 09. Fibularis (Peroneus) 72. Lateral Malleolus Tertius Tendon 21. Kager’s Fat Pad 07. Superior Extensor 15. Superior Fibular Retinaculum (Peroneal) Retinaculum 51. Deep Fibular Nerve 52. Anterior Tibial Artery 19. Calcaneal (Achilles) Tendon 16. Inferior Fibular 02. Tibialis Anterior Tendon (Peroneal) Retinaculum 42. Intermedial Dorsal 08. Inferior Extensor 73. Calcaneus Bone Cutaneous Nerve Retinaculum 43. Lateral Dorsal Cutaneous Nerve 44. Dorsalis Pedis Artery 11. Extensor Digitorum 32. Abductor Digiti Minimi Muscle Brevis Muscle 04. Extensor Hallucis Longus Tendon 48. Medial Tarsal Artery 06. Extensor Digitorum 10. Extensor Hallucis Longus Tendons Brevis Muscle 41. Medial Dorsal Cutaneous Nerve 49. Dorsal Metatarsal Artery 45. Deep Fibular (Peroneal) Nerve MEDIAL VIEW 22. Flexor Digitorum 46. Arcuate Artery Longus Muscle 68. Tibia 12. Dorsal Interossei Muscle 21. Kager’s Fat Pad 48. Medial Tarsal Artery 69. Medial Malleolus 27. Tibialis Posterior 81. Nail Tendon 18. Flexor Retinaculum 29. Abductor Hallucis Muscle 36. Flexor Muscle POSTERIOR VIEW PLANTAR VIEW 01. Tibialis Anterior Muscle 03. Extensor Hallucis 70. Interosseous Longus Muscle Membrane 23. Flexor Digitorum 05. Extensor Digitorum Longus Tendons Longus Muscle 26. Tibialis Posterior Muscle 14. Fibularis (Peroneus) 20. Soleus Muscle Brevis Muscle 24. Flexor Hallucis Longus Muscle 25. Flexor Hallucis Longus Tendon 67. Proper Plantar 66. Proper Plantar Digital Artery Digital Nerve 65. Proper Plantar Digital Nerve 80. Sesamoid Bone 31. Flexor Digitorum Brevis Tendons 19. Calcaneal (Achilles) Tendon 36. Flexor Muscle 29. -

Tibialis Posterior Muscle Pain Effects on Hip, Knee and Ankle Gait

Human Movement Science 66 (2019) 98–108 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Human Movement Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/humov Tibialis posterior muscle pain effects on hip, knee and ankle gait mechanics T Morten Bilde Simonsena,b, Aysun Yurtseverb,c, Ketill Næsborg-Andersenb, Peter Derek Christian Leutscherb,d, Kim Hørslev-Petersene, ⁎ Michael Skipper Andersenf, Rogerio Pessoto Hirataa, a Center for Sensory-Motoric Interaction (SMI®), Department of Health Science and Technology, Aalborg University, Fredrik Bajers Vej 7, DK-9220 Aalborg East, Denmark b Centre for Clinical Research, North Denmark Regional Hospital, Bispensgade 37, DK-9800 Hjoerring, Denmark c Department of Rheumatology, Hjørring Hospital, Bispensgade 37, DK-9800 Hjørrring, Denmark d Department of Clinical Medicine, Aalborg University, Søndre Skovvej 15, DK-9000, Denmark e King Christian 10th Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, University of Southern Denmark, Toldbodgade 3, DK-6300 Gråsten, Denmark f Department of Materials and Production, Aalborg University, Fibigerstraede 16, DK-9220 Aalborg East, Denmark ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: Tibialis posterior (TP) dysfunction is a common painful complication in patients Tibialis posterior with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which can lead to the collapse of the medial longitudinal arch. Dysfunction Different theories have been developed to explain the causality of tibialis posterior dysfunction. Gait In all these theories, pain is a central factor, and yet, it is uncertain to what extent pain causes the Experimental pain observed biomechanical alterations in the patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the Rheumatoid arthritis effect of experimental tibialis posterior muscle pain on gait mechanics in healthy subjects. Methods: Twelve healthy subjects were recruited for this randomized crossover study. -

Top 10 Positional-Release Therapy Techniques to Break the Chain of Pain, Part 1 Timothy E

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU All PTHMS Faculty Publications Physical Therapy & Human Movement Science 2006 Top 10 Positional-Release Therapy Techniques to Break the Chain of Pain, Part 1 Timothy E. Speicher Sacred Heart University David O. Draper Brigham Young University - Utah Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/pthms_fac Part of the Physical Therapy Commons, and the Somatic Bodywork and Related Therapeutic Practices Commons Recommended Citation Speicher, Tim and David O. Draper. "Top-10 Positional-Release Therapy Techniques to Break the Chjin of Pain: Part 1. Athletic Therapy Today 11.5 (2006): 69-71. This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Physical Therapy & Human Movement Science at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All PTHMS Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THERAPEUTIC MODALITIES David O. Draper, EdD, ATC, Column Editor Top 10 Positional-Release Therapy Techniques to Break the Chain of Pain, Part 1 Tim Speicher, MS, ATC, CSCS • Sacred Heart University David O. Draper, EdD, ATC • Brigham Young University OSITIONAL-RELEASE therapy (PRT) is a counterstrained tissue, decreasing abberent gamma and treatment technique that is gaining popu- alpha neuronal activity, thereby breaking the sustained P larity. The purpose of this two-part column contraction.1 Jones’s original work and PRT theory have