Top 10 Positional-Release Therapy Techniques to Break the Chain of Pain, Part 1 Timothy E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plantar Fascia-Specific Stretching Program for Plantar Fasciitis

Plantar Fascia-Specific Stretching Program For Plantar Fasciitis Plantar Fascia Stretching Exercise 1. Cross your affected leg over your other leg. 2. Using the hand on your affected side, take hold of your affected foot and pull your toes back towards shin. This creates tension/stretch in the arch of the foot/plantar fascia. 3. Check for the appropriate stretch position by gently rubbing the thumb of your unaffected side left to right over the arch of the affected foot. The plantar fascia should feel firm, like a guitar string. 4. Hold the stretch for a count of 10. A set is 10 repetitions. 5. Perform at least 3 sets of stretches per day. You cannot perform the stretch too often. The most important times to stretch are before taking the first step in the morning and before standing after a period of prolonged sitting. Plantar Fascia Stretching Exercise 1 2 3 4 URMC Orthopaedics º 4901 Lac de Ville Boulevard º Building D º Rochester, NY 14618 º 585-275-5321 www.ortho.urmc.edu Over, Please Anti-inflammatory Medicine Anti-inflammatory medicine will help decrease the inflammation in the arch and heel of your foot. These include: Advil®, Motrin®, Ibuprofen, and Aleve®. 1. Use the medication as directed on the package. If you tolerate it well, take it daily for 2 weeks then discontinue for 1 week. If symptoms worsen or return, then resume medicine for 2 weeks, then stop. 2. You should eat when taking these medications, as they can be hard on your stomach. Arch Support 1. -

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

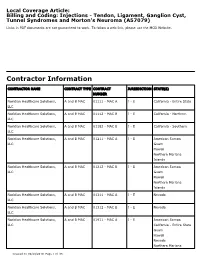

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. -

Advice and Exercises for Patients with Plantar Fasciitis

Advice and exercises for patients with plantar fasciitis This leaflet provides management advice and exercises for people diagnosed with plantar fasciitis, a condition causing pain in the heel, sole and /or arch of the foot. Structures of the foot The plantar fascia is a sheet or broad band of fibrous tissue that runs along the bottom of the foot. This tissue connects the heel to the base of the toes. Under normal circumstances, the plantar fascia supports the arch of the foot and acts as a shock absorbing “bow string” within the arch of the foot. With weight bearing, the foot flattens and the plantar fascia stretches, then springing you forward ready for the next step. While walking, the stresses placed on the foot can be one and a quarter times your body weight (this increases to two and three quarter times your body weight when running). Unsurprisingly then, that heel pain is common. If tension on this “bowstring” becomes too great, irritation or inflammation can occur causing pain. What is plantar fasciitis? Plantar fasciitis is a relatively common foot problem affecting up to 10-15% of the population. It can occur at any age. It is sometimes known as “policeman’s heel”. When placed under too much stress due to abnormal loading, the plantar fascia stretches causing micro tearing and degeneration of the tissue. It can lead to pain in the heel, across the sole of the foot and sometimes into the arch area of the foot too. These micro tears repair with scar tissue, which is less flexible than the fascia and can cause the problem to persist for many months. -

Plantar Fasciitis Exercises

Accurate Clinic 2401 Veterans Memorial Blvd. Suite16 Kenner, LA 70062 - 4799 Phone: 504.472.6130 Fax: 504.472.6128 www.AccurateClinic.com Plantar Fasciitis Exercise Getting the right plantar fasciitis exercise is imperative to ensure the injury doesn’t continue to affect performance. If not given the attention it needs, plantar fasciitis can flair up long after an athlete thinks they’ve recovered and badly damage training plans and competition aspirations. What is plantar fascia? Plantar fascia is a thick, fibrous band of connective tissue which originates at the heel bone and runs along the bottom of the foot in a fan-like manner, attaching to the base of each of the toes. A rather tough, resilient structure, the plantar fascia takes on a number of critical functions during running and walking. Although the fascia is invested with countless sturdy 'cables' of connective tissue called collagen fibres, it is certainly not immune to injury. In fact, about 5 to 10 per cent of all running injuries are inflammations of the fascia, an incidence rate which in the United States would produce about a million cases of plantar fasciitis per year, just among runners and joggers. Basketball players, tennis players, volleyballers, step-aerobics participants, and dancers are also prone to plantar problems, as are non-athletic people who spend a lot of time on their feet or suddenly become active after a long period of lethargy. Why does the fascia flare up? Although it is a fairly rugged structure, the plantar fascia is not very receptive to stretching, and yet stretching occurs in the fascia nearly every time the foot hits the ground. -

Plantar Fasciitis Stage 1

PLANTAR FASCIITIS STAGE 1 ADVICE Avoid those activities which aggravate your pain (e.g walking or running). SETS & REPS: N/A FREQUENCY: N/A AVOID FLIP-FLOPS Avoid wearing flip-flops SETS & REPS: N/A FREQUENCY: N/A AVOID HIGH HEELS Avoid high heels. SETS & REPS: N/A FREQUENCY: N/A PLANTAR FASCIA ICE MASSAGE Place a frozen water bottle on the floor and roll the bottle back and forth under your foot for 10 minutes. Do this at the end of each day and after activity. SETS & REPS: 10 mins FREQUENCY: Daily PLANTAR FASCIA MASSAGE Sitting, place a golf ball on the floor and roll the ball around under your foot concentrating on the tight, tender areas. SETS & REPS: 2-5 mins FREQUENCY: As needed © 2013 The Rehab Lab Limited. Used under license. No reproduction permitted without permission. www.therehablab.com PLANTAR FASCIITIS STAGE 1 PRONE GLUTEAL CONTRACTION Lie face-down and place your hands on your buttock muscles. Contract your gluteals, feeling the muscles tightening beneath your hands and hold for 5 seconds. Relax and repeat. SETS & REPS: 10 reps FREQUENCY: 1-2 x daily GLUTEAL STRETCH Sit on a chair and place your ankle on your opposite knee. With both hands, gently push down the knee of the crossed leg. Maintaining a straight back, bend forwards from the hips until you feel a stretch. Hold. SETS & REPS: 2 minute hold FREQUENCY: 1-2 x daily HAMSTRING STRETCH Place your heel on a knee-height table/chair with your knee slightly bent and tilt your pelvis forwards. While keeping your back straight, lean forwards until you feel a stretch in your hamstring. -

Plantar Fasciitis: a Degenerative Process (Fasciosis) Without Inflammation

CLINICAL PATHOLOGY Plantar Fasciitis A Degenerative Process (Fasciosis) Without Inflammation Harvey Lemont, DPM* Krista M. Ammirati, BS* Nsima Usen, MPH* The authors review histologic findings from 50 cases of heel spur surgery for chronic plantar fasciitis. Findings include myxoid degeneration with fragmentation and degeneration of the plantar fascia and bone marrow vascular ectasia. Histologic findings are presented to support the thesis that “plantar fasciitis” is a degenerative fasciosis without inflammation, not a fasciitis. These findings suggest that treatment regimens such as serial corticosteroid injections into the plantar fascia should be reevalu- ated in the absence of inflammation and in light of their potential to induce plantar fascial rupture. (J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 93(3): 234-237, 2003) Plantar fasciitis is presumed to be synonymous with occur with long-distance running may induce an in- inflammation of the plantar fascia. In fact, the suffix flammatory process, leading to fibrosis or degenera- “-itis” inherently implies an inflammatory disease. tion, and Sewell5 stated that the pain of plantar inflam- However, is plantar fasciitis really an inflammatory mation may sometimes be secondary to periosteal disorder? inflammation of the os calcis. Although authors writ- Plantar fasciitis is widely described in the litera- ing on the subject describe inflammation as being ture as having a multifactorial and widely disputed present in plantar fasciitis, they provide no objective etiology. Interestingly, in 1965, Lapidus and Guidotti,1 clinical or histologic evidence to support their claims. in their article entitled “Painful Heel,” stated that “the In addition, when photomicrographs are provided, name of painful heel is used deliberately in prefer- they are often mislabeled as showing inflammation. -

Plantar Fasciitis Standard of Care

BRIGHAM AND WOMEN’S HOSPITAL Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Standard of Care: Plantar Fasciitis Case Type / Diagnosis: (diagnosis specific, impairment/ dysfunction specific) ICD9 - 728.71 plantar fibromatosis Plantar fasciitis is an inflammatory condition that occurs as a result of overstressing the plantar fascia. It is the most common cause of inferior heel pain and has been diagnosed in patients from the ages of 8-80. 1-4 Plantar fasciitis affects approximately 10% of the population and is more commonly found in middle-aged women and younger male runners.2, 3, 5 A majority of the patients diagnosed with this inflammatory condition are over the age of 40.3 Bilateral symptoms can occur in 20-30% of those diagnosed with plantar fasciitis.6 However in these cases it is important to rule out other systemic processes such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Reiter’s disease, gout and ankylosing spondylitis.3, 6 The primary symptom of plantar fasciitis is pain in the heel when the patient first rises in the morning and when the plantar fascia is palpated over it’s origin at the medial calcaneal tuberosity.2-4, 6, 7 The plantar fascia (aponeurosis) is a thick fibrous band of connective tissue that originates at the medial and lateral tuberosities of the calcaneus. It runs longitudinally and has 3 portions, medial, central, and lateral. At the midfoot level, the fascia divides into 5 separate bands, which blend with the flexor tendon sheaths and transverse metatarsal ligaments and attach at the base of each proximal phalange. The central portion of the plantar fascia is the largest section. -

Understanding the First

CME / ORTHOTICS & BIOMECHANICS Goals and Objectives After reading this CME the practitioner will be able to: 1) Understand normal and abnormal function of the first ray with special emphasis on its integral role in medial longitudinal arch function and hypermobility. Understanding 2) Acquire knowledge of the various etiologic factors that result in first ray hypermobility. the First Ray 109 3) Appreciate its normal and abnormal motion along Here’s a review of its normal with its attendant bio and and abnormal function, identification, pathomechanics. and clinical significance. 4) Become familiar with vari- ous methods to subjectively and BY JOSEPH C D’AMICO, DPM objectively identify its presence. Welcome to Podiatry Management’s CME Instructional program. Our journal has been approved as a sponsor of Con- tinuing Medical Education by the Council on Podiatric Medical Education. You may enroll: 1) on a per issue basis (at $26.00 per topic) or 2) per year, for the special rate of $210 (you save $50). You may submit the answer sheet, along with the other information requested, via mail, fax, or phone. You can also take this and other exams on the Internet at www.podiatrym.com/cme. If you correctly answer seventy (70%) of the questions correctly, you will receive a certificate attesting to your earned credits. You will also receive a record of any incorrectly answered questions. If you score less than 70%, you can retake the test at no additional cost. A list of states currently honoring CPME approved credits is listed on pg. 144. Other than those entities currently accepting CPME-approved credit, Podiatry Management cannot guarantee that these CME credits will be acceptable by any state licensing agency, hospital, managed care organization or other entity. -

Contribution of Plantar Fascia and Intrinsic Foot Muscles in a Single-Leg Drop Landing and Repetitive Rebound Jumps: an Ultrasound-Based Study

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Contribution of Plantar Fascia and Intrinsic Foot Muscles in a Single-Leg Drop Landing and Repetitive Rebound Jumps: An Ultrasound-Based Study Masanori Morikawa 1 , Noriaki Maeda 1 , Makoto Komiya 1 , Arisu Hirota 1, Rami Mizuta 1, Toshiki Kobayashi 2, Kazuki Kaneda 1, Yuichi Nishikawa 3 and Yukio Urabe 1,* 1 Division of Sport Rehabilitation, Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-ku, Hiroshima 734-8553, Japan; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (N.M.); [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (A.H.); [email protected] (R.M.); [email protected] (K.K.) 2 Department of Biomedical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 11 Yuk Choi Road, Hung Hom, Hong Kong, China; [email protected] 3 Faculty of Frontier Engineering, Institute of Science & Engineering, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa 076-264-5111, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The plantar fascia and intrinsic foot muscles (IFM) modulate foot stiffness. However, it is Citation: Morikawa, M.; Maeda, N.; unclear whether the corresponding ultrasonography findings reflect it. This study aimed to examine Komiya, M.; Hirota, A.; Mizuta, R.; the effect of the plantar fascia and IFM morphologies on force attenuation during landing and Kobayashi, T.; Kaneda, K.; Nishikawa, reactivity when jumping in healthy adults (n = 21; age, 21–27 years). Thickness, cross-sectional area Y.; Urabe, Y. -

Evidence Based Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis Review of Literature

March 2007 Keeping Bodies in Motion ® by Joshua Dubin, DC, CCSP, CSCS S PORTS T HERAPY Evidence Based Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis Review of Literature Fig. 1A Superficial Fig. 1B Plantar Fascia twelve steps the plantar fascia becomes ABSTRACT Plantar Muscles Plantar fasciitis, a repetitive strain of the Foot stretched and the pain gradually injury of the medial arch and heel, is one diminishes. However, symptoms may of the most common causes of foot pain. resurface as throbbing, a dull ache, or The function of the plantar fascia is a fatigue-like sensation in the medial twofold: statically, it stabilizes the medial arch of the foot after prolonged periods longitudinal arch; dynamically, it restores of standing, especially on unyielding the arch and aids in reconfiguring the cement surfaces.5,6,7,8 foot for efficient toe-off. When this tissue Medial The plantar fascia is a thick, becomes damaged, pain and/or weakness Band fibrous, relatively inelastic sheet of may develop in the area. Risk factors of connective tissue originating from the plantar fasciits include structural Abductor medial heel, where it then passes over abnormalities, overweight, age-related Hallucis Central the superficial musculature of the foot degenerative changes, occupations or Band and inserts onto the base of each toe activities that require prolonged standing Abductor Lateral (figures 1A and 1B). The plantar fascia Flexor Band and/or ambulation, and training errors. Digitorum Digitorum is the main stabilizer of the medial Literature indicates that plantar fasciitis Minimi Brevis longitudinal arch of the foot against may be successfully treated using a ground reactive forces, and is instrumental conservative approach. -

A Guide Toplantar Fasciitis

WHAT IS PLANTAR FASCIITIS? If you're finding when you climb out of bed each morning that your first couple steps cause your foot and heel to hurt, this might be a sign of plantar fasciitis. This condition occurs when you strain the arch supporting fascial an A common condition that causes d it can result in small tears to pain in the heel is known as your fascial if you are repeatedly "Plantar Fasciitis" . The plantar straining it which leads to swelling fascia is a fascial band that attaches and pain. It occurs in one or both to the toes and heel, and extends feet. along the arch of your foot. If your plantar fascia is irritated, it can Many individuals with plantar get inflamed and can become fasciitis experience pain with their painful when you walk or stand. first few steps after sitting for too Although this condition is more long or just getting out of bed in the common in older adults, people morning. After a few steps, the pain who are younger can also develop it and stiffness seems to lessen, if they are always on their feet, however the pain can increase as such as soldiers, nurses, teachers, you go about your day, especially if or athletes. you are standing for some time or have to climb stairs. WHO IS AT RISK? Age Age plays a factor. Elderly people are at a higher risk for suffering with foot issues which can impair their function and balance. Your feet begin to get wider and flatten as you get older. -

Plantar Fasciitis Brochure

Plantar Fasciitis Plantar Fasciitis Plantar Fasciitis Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of heel pain for which professional care is sought. This is caused by irritation of the plantar fascia — a thickened fibrous band that runs from the heel to the ball of the foot. This band pulls on the heel bone, raising the arch of the foot as it pushes off the ground. If the feet move incorrectly, the plantar fascia may become irritated and swell, causing plantar fasciitis. The plantar fascia is made up of three distinct parts: the medial, central and lateral bands. The central plantar fascia is the thickest and strongest section, and this segment is also the most likely to be involved with plantar fasciitis. Symptoms Calcaneus The most common symptom of Plantar Fasciitis is pain Area of pain at the bottom of the foot, first thing in the morning or after prolonged sitting. It may lessen after walking, but returns with continued activity. Plantar fascia Treatment Anti-inflammatory drugs: Equipment: Oral anti-inflammatory medication such as ibuprofen Night splints keep the plantar fascia from getting will relieve pain and reduce swelling. tighter at night. Over-the-counter heel cushions and gel heel inserts along with well-cushioned, “shock-absorbent” shoes are also helpful. 3 Plantar Fasciitis Stretching Exercises Plantar Fasciitis Stretching Exercises Stretching exercises SOLEUS STRETCH ICE BOTTLE TOE FLEXION/EXTENSION GASTROCNEMIUS STRETCH Fill a 20 oz. bottle with water and freeze it. Sit in a chair and roll the bottle up and down the bottoms of your feet for five to 10 minutes.