Turkish Male Viewers' Perceptions of Female

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eccho Rights

//// CommentarY BY FABRICIO Ferrara Turkey, Home of Content at Mipcom 2015 riven by the Istanbul Chamber of Commerce (ITO) and several Government entities such us the D Ministry of Culture and Tourism and Ministry of Economy, Turkey Country of Honour hosts at MIPCOM 2015 an important series of conferences, screenings and activities on 4-8 October, 2015. Under the motto Turkey Home of Content, the program a trade delegation consisting of 33 Turkish companies, promises to be a smart experience for the market partici- which are taking part o the matchmaking meetings. pants, and a great opportunity for the Turkish industry to The Official Welcome Party on Monday at Martinez be (much more) known by the media world. A dedicated Hotel is sponsored by TRT, while ITV Inter Medya and website, www.turkeyhomeofcontent.com, has Global Agency host their own parties on Tuesday and Published by been previously launched to show the country news. Wednesday, respectively, and ATV organizes a launch Editorial Prensario SRL Turkish companies attend MIPCOM with its different at Carlton Hotel on Monday. Regarding meeting spaces, Lavalle 1569, Of. 405 C1048 AA K branches, including networks, production and distri- there is a common sector inside the Palais des Festivals Buenos Aires, Argentina bution companies, digital media and advertisement for meetings (106.5sqm2) and a tent outside (300sqm2). Phone: (+54-11) 4924-7908 business along with stars, screenwriters, producers and PRENSARIO has been covering the Turkish industry since Fax: (+54-11) 4925-2507 directors. A major audiovisual forum is taking place of- early 2005 and, it can be assured, the evolution has been fering a deeper look at the growing media landscapes: notorious. -

Akmerkez Gayrimenkul Yatirim Ortakliği Anonim Şirketi

AKMERKEZ GAYRİMENKUL YATIRIM ORTAKLIĞI ANONİM ŞİRKETİ ANNUAL REPORT COVERING THE PERIOD OF 01.01.2015 - 31.12.2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................................................................................... 2 Akmerkez in Brief ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Milestones of Akmerkez ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Sectoral Activities in 2015 ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Message from the Board of Directors .................................................................................................................... 9 Message from the General Manager ................................................................................................................... 10 Management of the Shopping Center .................................................................................................................. 11 Organization, Capital and Shareholding Structures of the Company and Changes to Them During the Accounting Period: ............................................................................................................................................... 16 Organization Chart: ............................................................................................................................................. -

Karar No : 567 Karar Tarihi : 07/12/2013 2972 Sayılı Mahalli

Karar No : 567 Karar Tarihi : 07/12/2013 2972 sayılı Mahalli İdareler ile Mahalle Muhtarlıkları ve İhtiyar Heyetleri Seçimi Hakkında Kanun’un 8. maddesinin birinci fıkrasında yer alan; “Mahalli idareler seçimleri be ş yılda bir yapılır. Her seçim döneminin be şinci yılındaki 1 Ocak günü seçimin ba şlangıç tarihidir. Aynı yılın Mart ayının son Pazar günü oy verme günüdür.” hükmüne istinaden, mahalli idareler seçimleri 30 Mart 2014 Pazar günü yapılacaktır. 298 sayılı Seçimlerin Temel Hükümleri ve Seçmen Kütükleri Hakkında Kanun’un 55/A maddesinin son fıkrasında; “Ülke çapında yayın yapan özel radyo ve televizyonların hangileri oldu ğunu belirlemeye Yüksek Seçim Kurulu yetkilidir. Yüksek Seçim Kurulunun buna ili şkin kararı Resmî Gazete’de yayımlanır.” hükmü yer almaktadır. Bu nedenle, ülke çapında (ulusal düzeyde) yayın yapan özel radyo ve televizyonlar ile bölgesel yayın tipinde olup, uydu yayını yapan televizyonların belirlenerek ilân edilmesi amacıyla Kurulumuzun 14/9/2013 tarih, 2013/374 sayılı kararı ile olu şturulan Komisyon yaptı ğı çalı şmaları tamamlayarak konu hakkında düzenledi ği karar tasla ğını Kurulumuza sunmu ş olmakla, konu incelenerek; GERE Ğİ GÖRÜ ŞÜLÜP DÜ ŞÜNÜLDÜ: Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Anayasası’nın 79. maddesinde; seçimlerin ba şlamasından bitimine kadar, seçimin düzen içinde yönetimi, dürüstlü ğü ile ilgili bütün i şlemleri yapma ve yaptırma, seçim süresince ve seçimden sonra seçim konularıyla ilgili bütün yolsuzlukları, şikâyet ve itirazları inceleme ve kesin karara ba ğlama görevinin Yüksek Seçim Kuruluna ait oldu -

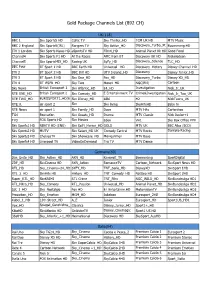

Channel Listล่าสุด2.Xlsx

Gold Package Channels List (892 CH) UK(118) BBC 1 Skv Sports5 HD Celtic TV Sky Thriller_HD TCM UK HD MTV Music BBC 2 England Skv Sports5(IRL) Rangers TV Sky Action_HD Discovery_Turbo_Xt Boomerang HD ITV 1 London Skv Sports News HD eSportsTV HD Film4_HD Animal Planet Uk HD Good Food Channel4 Skv Sports F1 HD At the Races AMC from BT Discovery UK HD Nickelodeon Channel5 Skv SportsMIX_HD Racing UK SyFy_HD Discovery_Science TLC_HD BBC Four BT Sport 1 HD BBC Earth HD Universal _HD Discovery_History Disney Channel_HD ITV 2 BT Sport 2 HD BBC Brit HD UTV Ireland_HD Discovery Disney Junior_HD ITV 3 BT Sport 3 HD Skv One_HD Fox_HD Discovery_Turbo Disney XD_HD ITV 4 BT_ESPN_HD Sky Two More4_HD NGC(EN) Cartoon Sky News British Eurosport 1 Skv Atlantic_HD E4_HD Investigation Nick_Jr_UK RTE ONE_HD British Eurosport 2 Skv Comedy_HD E Entertainment TV Crime&Investigation Nick_Jr_Too_UK RTE TWO_HD EUROSPORT1_HD(E Skv Disney_HD Alibi H2 NickToons_UK RTE jr. eir sport 2 Skv Skv living SkyArtsHD Baby tv RTE News eir sport 1 Skv Family_HD Dave MTV Hits Cartonitoo TG4 Boxnation Skv Greats_HD Drama MTV Classic Nick Junior+1 TV3 FOX Sports HD Skv Movies Eden VH1 Sky Box Office PPV Skv Sports1 HD NBATV HD (ENG) Skv SciFi_Horror_HD GOLD MTV UK BBC Alba (SCO) Skv Sports2 HD MUTV Skv Select_HD UK Comedy Central MTV Rocks Dantoto Racing Skv Sports3 HD ChelseaTV Skv Showcase_HD Movies4men MTV Base Skv Sports4 HD Liverpool TV VideoOnDemand Tru TV MTV Dance Germany(69) Das_Erste_HD Sky_Action_HD AXN_HD Kinowelt_TV Boomerang SportDigital ZDF_HD SkvCinema HD AXN_Action -

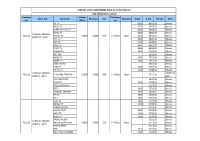

27 Ekim TV Ve Radyo Listesi 251020008 V2

SEMBOL POLARİZASY KAPSAMA FREKANS ORANI PAKET ADI KANAL ADI ON ALANI (FREQ.) ( SYMBOL FEC (BOUQUET NAME) (CHANNEL NAME) (POLARIZATI (COVERAGE RATE) (MHZ) ON) AREA) (MSYM/S) * TÜRKSAT TANITIM DİJİTAL (BATI) 12731 3333 3/4 V - DİKEY BATI (WEST) OTOMATİK TARAMA STV MEHTAP TV STV PAKET (BATI) 10960 13000 5/6 H-YATAY BATI (WEST) YUMURCAK S HABER HAZAR TV 10969 2400 5/6 H -YATAY BATI (WEST) KANAL D PAKET KANAL D 10970 30000 5/6 V-DİKEY BATI (WEST) NTV CNBC-E NTV PAKET E2 11054 30000 5/6 H-YATAY DOĞU(EAST) NTV SPOR KRAL TV TRT 1 TRT 2 TRT PAKET DOĞU TRT INT 11094 24444 3/4 H -YATAY DOĞU (EAST) TRT 4 TRT 5 ÇAY TV DOĞU TV POWER TV RUMELİ TV SHOPPING TV EXPO CH. TURKSAT BATI PAKET NATURAL LİFE 11096 30000 5/6 V -DİKEY BATI (WEST) 1 FASHIONE TV NR1 TV FLASH TV KARADENİZ TV KIBRIS ADA TV YABAN TV HABERTÜRK HABERTÜRK PAKET 11194 7200 3/4 H-YATAY BATI (WEST) KANAL 1 BRT INT 11524 4557 3/4 V -DİKEY BATI (WEST) İCTİMAİ TV 11554 2916 2/3 H -YATAY DOĞU -EAST TRT TÜRK ASYA 11581 4444 3/4 H -YATAY DOĞU -EAST AZER TV 11607 3750 2/3 H -YATAY DOĞU -EAST ATV DOĞU 11628 6666 5/6 H -YATAY DOĞU -EAST KANAL TÜRK PAKET KANAL TÜRK 11642 10370 5/6 H-YATAY DOĞU(EAST) SES TV 11712 2963 3/4 V - DİKEY BATI (WEST) JOJO (şifreli) LİG TV (şifreli) DIGI (şifreli) İZ TV (şifreli) DIJITURK PAKET 11729 15555 5/6 V - DİKEY BATI (WEST) ACTIONMAX (şifreli) MAX TV ASK TV TÜRKMAX (şifreli) KANAL AVRUPA KANAL AVRUPA HALAY 11742 2965 5/6 V-DİKEY BATI (WEST) BERAT TÜRKSAT TANITIM AL JAZEERA TV TÜRKSAT DOĞU AL JAZEERA TV ENG. -

Hosgeldiniz El Kitabi

Digiturk Kolay Kullanım Rehberi Digiturk Üyelik Numaranız: Digiturk Teknik Servis Bilgileriniz: V1: 12.9.2011 © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. Inc. All rights Enterprises, © Disney İÇİNDEKİLER 1 İlk faturanız hakkında ................................................................................................... 4 2 Faturamı nasıl ödeyebilirim? ................................................................................. 6 3 DIGIMOBIL 3555’ten neler yapabilirim? .................................................... 7 4 Hangi kanal hangi numarada? .................................................................... 8-9 5 Yayın akışına nasıl ulaşabilirim? ................................................................... 10 6 Digiturk kumandasını nasıl kullanırım? .................................................. 12 7 PIN kodu nedir? PIN kodu nasıl değiştirilir? ....................................... 13 8 Digiturk “Online İşlemler”den neler yapabilirim? ......................... 14 Digiturk’e 9 Digiturk yardım ................................................................................................................... 16 hoş geldiniz. 9.1 Sinyal seviyesinde azalma var. Ne yapmalıyım? ........................................................ 17 9.2 Bazı kanalları izleyemiyorum, eksik kanallar var. Ne yapmalıyım? ....................... 18 Digiturk ile olan birlikteliğinizde 9.3 Görüntü ve/veya ses yok, görüntüde dalgalanmalar ve size yardımcı olacağına donmalar var. Ne yapmalıyım? .................................................................................... -

FEC Polarizasy on Kapsama V-Pid A-Pid Format Şifre A9 TV 6502 6602 S

TÜRKSAT UYDU HABERLEŞME KALO TV ve İŞLETME A.Ş YENİ DÖENEM TV LİSTESİ Transpon Frekans Polarizasy Paket Adı Kanal Adı SR (ksps) FEC Kapsama V-pid A-pid Format Şifre der (MHz) on A9 TV 6502 6602 SD Şifresiz AKILLI TV 6503 6603 SD Şifresiz G.ANTEP OLAY TV 6501 6601 SD Şifresiz GENÇ TV 6500 6600 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT ANKARA T3A_01 HAYAT TV 12524 22500 '2/3' V - Dikey West 6504 6604 SD Şifresiz PAKET 15 - BATI HRT TV 6505 6605 SD Şifresiz IMC TV 6508 6608 SD Şifresiz LINE TV 6507 6607 SD Şifresiz TİVİTİ TV 6506 6606 SD Şifresiz ADANA TV 5403 5503 SD Şifresiz ART FM 5510 SD Şifresiz BARIŞ TV 5405 5505 SD Şifresiz BEDİR TV 5407 5507 SD Şifresiz CEM RADYO 5511 SD Şifresiz CEM TV 5401 5501 SD Şifresiz ÇİFTÇİ TV 5408 5508 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT ANKARA CRYPTOW T3A_01 ESKİŞEHİR STAR FM 12559 27500 '2/3' V - Dikey West 5512 SD PAKET 4 - BATI ORKS HAK MESAJ FM 5515 SD Şifresiz KOZA TV 5404 5504 SD Şifresiz POLİS RADYOSU 5513 SD Şifresiz SRT 1 5406 5506 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT TANITIM 5409 5509 SD Şifresiz TV 41 5400 5500 SD Şifresiz TV 5 5402 5502 SD Şifresiz 7/24 TV 5604 5704 SD Şifresiz DENGE TV 5608 5708 SD Şifresiz ERKAM RADYO 5714 SD Şifresiz KANAL FIRAT 5609 5709 SD Şifresiz MGC TV 5606 5706 SD Şifresiz OLAY TV 5601 5701 SD Şifresiz RADYO MÜZİK 5711 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT ANKARA T3A_02 RADYO SLOW TIME 12605 27500 '2/3' V - Dikey West 5712 SD Şifresiz PAKET 6 - BATI RADYO SPOR 5713 SD Şifresiz RTV 5610 5710 SD Şifresiz SHOPPING CHANNEL 5605 5705 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT ANKARA T3A_02 12605 27500 '2/3' V - Dikey West PAKET 6 - BATI TV 1 5603 5703 SD Şifresiz TV -

Ownership Structure of the Biggest Media Conglomerates in Turkey

APPENDIX TABLE 2: OWNERSHIP STRUCTURE OF THE BIGGEST MEDIA CONGLOMERATES IN TURKEY CONGLOMERATE MEDIA OTHER SECTORS Doǧan Group Newspaper Hurriyet, Posta, Fanatik, Hurriyet Energy Doǧan Energy Daily News, TME (Boyabat Electricity Production ve Trade) Giresun Aslancik Dam, Magazine Doǧan Burda Magazine Mersin RES, Sah RES, D-Tes Electric Energy Wholesale, Gas Plus Erbil Book Publishing Doǧan Egmont, Doǧan Books Aytemiz Petrol Publishing and Distribution Doǧan Distribution, Retail D&R Magazine Marketing Planning, Industry Celik Halat, Ditas (Automative Side Industry), Doǧan Printing Center Doǧan Organic Products News Agency DHA Real Estate Marketing Milpa TV Kanal D, CNN Turk, tv2, Dream TV, Finance DD Estate Finance Kanal D Romanya, Euro D Tourism Milla Radio Radyo D, Slow Turk, CNN Turk Radyo TV and Music Production D Productions, lnDHouse, Kanal D Home Video, Doǧan Music Company Digital TV Platform D-Smart Online Media hurriyet.com.tr, posta.com.tr, fanatik.com.tr, radikal.com.tr, cnnturk.com, kanald.com.tr, netd.com, hurriyetaile.com, mahmure.com, bigpara.com Online Commerce MedyaNet, arabam.com, hurriyetemlak.com, hurriyetoto.com, yenibiris.com, ekolay.net, yakala.co, Other Activities Doǧan International Commerce, Doǧan Factoring Social Activities Aydın Doǧan Foundation Doğuş Group TV NTV, Star TV, CNBC-E, NTV SPOR, NTV Banking and Finance Garanti Bank, Garantibank International N.V., Spor, Smart HD, Kral TV, Kral Pop TV, e2 Garanti Bank SA, Garantibank Moscow, Garanti Romania, Garanti Life Internet ntv.com, ntvspor.net, tvyo.com, -

The Political Economy of the Media in Turkey: a Sectoral Analysis

TESEV Democratization Program Media Studies Series - 2 The Political Economy of the Media in Turkey: A Sectoral Analysis Ceren Sözeri Zeynep Güney DEMOCRATIZATION PROGRAM The Political Economy of the Media in Turkey: A Sectoral Analysis Ceren Sözeri Zeynep Güney The Political Economy of the Media in Turkey: A Sectoral Analysis Türkiye Ekonomik ve Bankalar Cad. Minerva Han Sosyal Etüdler Vakf› No: 2 Kat: 3 Turkish Economic and Karaköy 34420, İstanbul Social Studies Foundation Tel: +90 212 292 89 03 PBX Fax: +90 212 292 90 46 Demokratikleşme Program› [email protected] Democratization Program www.tesev.org.tr Authors: Production: Myra Ceren Sözeri Publication Identity Design: Rauf Kösemen Zeynep Güney Cover Design: Serhan Baykara Page Layout: Gülderen Rençber Erbaş Prepared for Publication by: Coordination: Sibel Doğan Esra Bakkalbaşıoğlu, Pre-print Coordination: Nergis Korkmaz Mehmet Ekinci Printed by: İmak Ofset Editing: Circulation: 500 copies Josee Lavoie TESEV PUBLICATIONS ISBN 978-605-5832-93-3 Copyright © September 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced electronically or mechanically (photocopy, storage of records or information, etc.) without the permission of the Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation (TESEV). The viewpoints in this report belong to the authors, and they may not necessarily concur partially or wholly with TESEV’s viewpoints as a foundation. TESEV would like to extend its thanks to European Commission, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Turkey, Open Society Foundation Turkey, and TESEV -

![[Itobiad], 2019, 8 (4): 2394/2423](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1653/itobiad-2019-8-4-2394-2423-2331653.webp)

[Itobiad], 2019, 8 (4): 2394/2423

[itobiad], 2019, 8 (4): 2394/2423 Kamu Değeri Yapımı Çerçevesinde Türkiye Radyo ve Televizyon Kurumu1 The Turkish Radio and Television Corporation within the Frame of Creating a Public Value Serkan ÖKTEN Dr, T.C. Cumhurbaşkanlığı İletişim Başkanlığı Dr, Presidency of the TR Directorate of Communications [email protected] Orcid ID: 0000-0001-9531-3373 Makale Bilgisi / Article Information Makale Türü / Article Type : Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Geliş Tarihi / Received : 08.02.2019 Kabul Tarihi / Accepted : 18.09.2019 Yayın Tarihi / Published : 25.10.2019 Yayın Sezonu : Ekim-Kasım-Aralık Pub Date Season : October-November-December Atıf/Cite as: ÖKTEN, S. (2019). Kamu Değeri Yapımı Çerçevesinde Türkiye Radyo ve Televizyon Kurumu. İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Araştırmaları Dergisi, 8 (4), 2394- 2423. Retrieved from http://www.itobiad.com/tr/issue/49747/524760 İntihal /Plagiarism: Bu makale, en az iki hakem tarafından incelenmiş ve intihal içermediği teyit edilmiştir. / This article has been reviewed by at least two referees and confirmed to include no plagiarism. http://www.itobiad.com/ Copyright © Published by Mustafa YİĞİTOĞLU Since 2012- Karabuk University, Faculty of Theology, Karabuk, 78050 Turkey. All rights reserved. 1 Bu çalışma 23-25 Eylül 2018 tarihlerinde Alanya’da düzenlenen I. Uluslararası İnsan ve Toplum Bilimleri Araştırmaları Kongresinde sunulan aynı başlıklı sözlü bildirinin genişletilmesiyle oluşturulmuştur. Serkan ÖKTEN Kamu Değeri Yapımı Çerçevesinde Türkiye Radyo ve Televizyon Kurumu Öz Kamu değeri yönetimi anlayışı, genel itibariyle kamu işletmeciliğinden farklı olarak kamu hizmeti görmede esas olanın kamu değeri yaratmak olduğunu kabul ederek kısa vadede elde edilecek karla ilgilenmemektedir. Ancak, ölçülmesi noktasında daha fazla çalışmaya ihtiyaç duyulmaktadır. Bu doğrultuda bu çalışmada bu ihtiyaca hizmet etmek amacıyla hazırlanmıştır. -

Aylık Voltaj Raporu Ekim 2017 Sektörde Dönemsel Mecra Bazlı Değişim TV Ve Sinemada Geçen Yıl Aynı Döneme Göre Kullanım Yoğunluğu Artmıştır

Aylık Voltaj Raporu Ekim 2017 Sektörde Dönemsel Mecra Bazlı Değişim TV ve sinemada geçen yıl aynı döneme göre kullanım yoğunluğu artmıştır. TV – GRP Gazete – st/cm Dergi– Sayfa Sayısı 242.172 GRP 3.068.154 st/cm 6.118 sayfa (%9,1) (-%10,4) (-%5,9) Radyo – Süre (Sn) Açıkhava – Ünite Sinema – Süre (Sn) 7.097.031 sn 272.930 adet 171.844.620 sn (-%9,8) (-%9,9) (%40,9) Kaynak : Bileşim Medya, Dönem : Ekim 2017 / 2016 , Hedef Kitle : Tüm Kişiler Açıklama : Karşılaştırma yapılırken sadece mecranın yıllar bazında raporlandığı data kriter alınmıştır. Televizyon Ölçülen Kanalların İzlenme Payları Tüm gün boyunca performansı en yüksek kanal ATV. 10,0 8,8 8,5 7,9 7,0 5,8 4,1 3,5 3,2 1,6 1,6 1,6 1,0 0,9 0,9 0,7 0,4 0,4 TRT TRT TRT Disney Minika Planet Atv Star Fox Show TV Kanal D TV8 Kanal 7 TRT 1 Beyaz TV TEVE2 TRT Spor TV8,5 Çocuk Haber Belgesel Channel Çocuk Çocuk Tüm Gün 10,0 8,8 8,5 7,9 7,0 5,8 4,1 3,5 3,2 1,6 1,6 1,6 1,0 0,9 0,9 0,7 0,4 0,4 Gündüz 10,4 7,3 6,5 6,9 4,9 4,8 5,3 6,3 2,4 1,6 2,1 1,6 0,7 1,0 1,4 1,1 0,7 0,3 Akşam 10,7 10,3 10,1 8,9 8,8 6,7 3,5 2,1 4,0 1,5 1,2 1,4 1,2 0,8 0,6 0,6 0,3 0,3 Kaynak : TNS / Kantar Medya, Dönem : Ekim 2017, Hedef Kitle : Tüm Kişiler Gündüz:08:00-17:59; Akşam: 18:00-23:59 Tematik Kanalların İzlenme Payları Tüm gün izlenme performansında öne çıkanlar : A Haber ve 360 1,8 1,6 1,5 1,3 1,2 1,1 1,0 1,0 0,9 0,8 0,7 0,5 0,4 0,3 A Haber 360 A Spor A2 TV CNN Türk NTV Spor NTV TLC Habertürk TGRT Haber Halk TV Flash Ülke TV TRT Müzik Kaynak : TNS / Kantar Medya, Dönem : Ekim 2017, Hedef Kitle : Tüm Kişiler *Haber kanalları pembe ile renlendirilmiştir. -

Issue Full File

İkinci Dalga Feminizmin Kozmetik Reklamlarının Görsel-Metinsel Tasarımı Üzerindeki Etkisi Dunkirk Filminde Ulusal Kimliğin ve Militarizmin İnşası Sosyal Medya ve Yerel Seçimler: Ak Parti #Gönülbelediyeciliği Etiketi Üzerine Bir Analiz Lise Öğrencilerinin Ders Dışı Etkinliklere Katılım Durumlarına Göre İletişimci Biçimlerinin İncelenmesi Gündem Belirleme Kuramı Bağlamında Twitter ve İnternet Gazetelerinin Karşılaştırılması: Hürriyet ve Milliyet Gazeteleri Örneği 'Narsistagram': Instagram Kullanımında Narsisizm Speed, Simultaneity and Interaction in New Media: A Study on Mobile Application News Kurumsal Halkla İlişkilerin Etkinliğini Ölçme: STK Gönüllüleri Üzerine Bir Araştırma Dijital Risk Toplumunda Meydan Okuma Videoları ve Çocuklar: Adana'da Ortaöğretim Öğrencilerine Yönelik Bir Alan Araştırmasından Bulgular The Turkish-German Affair in Films: A Dreamworld or a Netherworld? Dijital Çağda Bilginin Değişen Niteliği ve İnfobezite: Z Kuşağı Üzerine Bir Odak Grup Çalışması Yeni Medya Araştırmalarında Yöntemler ve Araçlar Ne Kadar Yeni? Türkiye'deki Lisansüstü Tezlere Dair Bir Meta Analiz Çalışması Dijital Çağda Medya: Makine Öğrenmesi, Algoritmik Habercilik ve Gazetecilikte İşlevsiz İnsan Sorunsalı Medya ve Kültür Endüstrisi Eleştirisinin Yeniden Üretimi Mümtaz Turhan'ın Türk İletişim Araştırmalarına Katkıları Meslek Liselerinde İletişim Eğitimi Üzerine Bir Betimleme Journal of Selçuk Communication Cilt/Volume 13 Sayı/Number 1 Ocak/ January 2020 SELÇUK İLETİŞİM JOURNAL OF SELCUK COMMUNICATION JANUARY 2020 Volume 13 Number 1 SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ İLETİŞİM FAKÜLTESİ AKADEMİK DERGİSİ OCAK 2020 Cilt 13 Sayı 1 e-ISSN 2148-2942 Sahibi Dr. Ahmet KALENDER Editör Editör Yardımcıları Alan Editörleri Dr. Bünyamin AYHAN Dr. Tuba LİVBERBER Dr. Meral SERARSLAN Dr. Burçe AKCAN Dr. Banu TERKAN Arş. Gör. Enes BALOĞLU Dr. İmran ASLAN Dr. Hasret AKTAŞ Yöntem ve İstatistik Editörü Dr. Abdullah KOÇAK Dil Editörü Dr. M.