Nuclear Futures: Western European Options for Nuclear Risk Reduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Otfried Nassauer * 20

Wir nehmen Abschied von unserem Freund, Kollegen und Mitstreiter Otfried Nassauer * 20. August 1956 † 1. Oktober 2020 Otfried Nassauer war seit 1991 Leiter des Berliner Informationszentrums für Transatlantische Sicherheit (BITS) und hat über viele Ländergrenzen hinweg tragfähige friedenspolitische Netzwerke aufgebaut. Als Experte für strategische Fragen, Waffensysteme und Rüstungskontrolle war er mit seinem fundierten Wissen ein äußerst gefragter Ratgeber der Friedensbewegung, der Medien, der Kirchen und der Politik, aber auch ein sehr respektierter Gesprächspartner von Vertretern der Bundeswehr. Großzügig stellte er sein umfassendes Wissen, seine Recherche-Ergebnisse und seine Artikel zur Verfügung, wenn es darum ging, in der Öffentlichkeit den Argumenten für Abrüstung und gegen weitere Aufrüstung und Krieg breiteres Gehör zu verschaffen. Sein profundes Detailwissen war immer hilfreich, aber auch herausfordernd und zum Weiterdenken anregend. Seine Erkenntnisse sind jahrzehntelang in unzählige fachwissenschaftliche und publizistische Beiträge eingeflossen. Für die Friedensbewegung war seine © Wolfang Borrs Arbeit von herausragender Bedeutung. Aus Otfrieds Studien und Untersuchungen ergaben sich oftmals konkrete friedenspolitische Forderungen und Aktionen. Das Ziel einer friedlicheren Welt spornte ihn in seinem Engagement an. Eine Johannes Ahlefeldt, Referent der SPD-Bundestagsfraktion, Berlin; Birgit und Michael Ahlmann, ex. BR-V, Blu- menschliche Welt ohne Krieg und Gewalt war für diesen herzensguten und wahr- menthal; Roland Appel, -

Tailored Deterrence - a French Perspective

50 TAILORED DETERRENCE - A FRENCH PERSPECTIVE Bruno TERTRAIS France is not at the forefront of the debate within NATO on the future of deterrence and retains a fairly conservative nuclear policy. However, the evolution of the French nuclear deterrent has been largely in tune with US and UK policies. Nuclear Deterrence With Smaller Arsenals Nuclear weapons will remain the ultimate guarantee of a nation’s survival for the foreseeable future. There is no alternative means of defense on the horizon which may threaten in a credible way the complete destruction of a State as a coherent entity, in just a few minutes. Conventional weapons could conveivably do the job, but only through repeated and multiple raids and with a lesser guarantee of success. Moreover, conventional weapons cannot instill in the adversary’s mind the very peculiar fear induced by nuclear weapons. Biological weapons are arguably as scary as nuclear ones - and perhaps even more so, in particu- lar for public opinion. But their use can be controlled only with difficulty. More importantly, they are not able to physically destroy government buildings, factories, command posts and arsenals. Unless perhaps deployed in space in very large numbers, strategic defenses will not be effective against a large number of missiles equipped with decoys and multiple warheads. Finally, threatening some particular hardened targets will continue to be possible only by nuclear means. But future deterrence will be ensured with smaller nuclear arse- nals. In the coming twenty years, Western nuclear stockpiles will continue *Senior Research Fellow, Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, France. 51 to be reduced. -

Air and Space Power Journal: Winter 2009

SPINE AIR & SP A CE Winter 2009 Volume XXIII, No. 4 P OWER JOURN Directed Energy A Look to the Future Maj Gen David Scott, USAF Col David Robie, USAF A L , W Hybrid Warfare inter 2009 Something Old, Not Something New Hon. Robert Wilkie Preparing for Irregular Warfare The Future Ain’t What It Used to Be Col John D. Jogerst, USAF, Retired Achieving Balance Energy, Effectiveness, and Efficiency Col John B. Wissler, USAF US Nuclear Deterrence An Opportunity for President Obama to Lead by Example Group Capt Tim D. Q. Below, Royal Air Force 2009-4 Outside Cover.indd 1 10/27/09 8:54:50 AM SPINE Chief of Staff, US Air Force Gen Norton A. Schwartz Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Stephen R. Lorenz Commander, Air University Lt Gen Allen G. Peck http://www.af.mil Director, Air Force Research Institute Gen John A. Shaud, USAF, Retired Chief, Professional Journals Maj Darren K. Stanford Deputy Chief, Professional Journals Capt Lori Katowich Professional Staff http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Darlene H. Barnes, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director of Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager The Air and Space Power Journal (ISSN 1554-2505), Air Force Recurring Publication 10-1, published quarterly, is the professional journal of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the http://www.au.af.mil presentation and stimulation of innovative thinking on military doctrine, strategy, force structure, readiness, and other matters of national defense. -

Continuity / Change: Rethinking Options for Trident Replacement

CONTINUITY / CHANGE: RETHINKING OPTIONS FOR TRIDENT REPLACEMENT DR. NICK RITCHIE Dr. Nick Ritchie Department of Peace Studies BRADFORD DISARMAMENT RESEARCH CENTRE University of Bradford April 2009 DEPARTMENT OF PEACE STUDIES : UNIVERSITY OF BRADFORD : JUNE 2010 About this report This report is part of a series of publications under the Bradford Disarmament Research Centre’s programme on Nuclear-Armed Britain: A Critical Examination of Trident Modernisation, Implications and Accountability. To find out more please visit www.brad.ac.uk/acad/bdrc/nuclear/trident/trident.html. Briefing 1: Trident: The Deal Isn’t Done – Serious Questions Remain Unanswered, at www.brad.ac.uk/acad/bdrc/nuclear/trident/briefing1.html Briefing 2: Trident: What is it For? – Challenging the Relevance of British Nuclear Weapons, at www.brad.ac.uk/acad/bdrc/nuclear/trident/briefing2.html. Briefing 3: Trident and British Identity: Letting go of British Nuclear Weapons, at www.brad.ac.uk/acad/bdrc/nuclear/trident/briefing3.html. Briefing 4: A Regime on the Edge? How Replacing Trident Undermines the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, at www.brad.ac.uk/acad/bdrc/nuclear/trident/briefing4.html. Briefing 5: Stepping Down the Nuclear Ladder: Options for Trident on a Path to Zero, at www.brad.ac.uk/acad/bdrc/nuclear/trident/briefing5.html. About the author Dr. Nick Ritchie is a Research Fellow at the Department of Peace Studies, University of Bradford. He is lead researcher on the Nuclear-Armed Britain programme. He previously worked for six years as a researcher at the Oxford Research Group on global security issues, in particular nuclear proliferation, arms control and disarmament. -

Easter 1956.Pdf

Cables: “Kitty Malta’* Telephones: Central 4028 * THE*STARS*CO. * Exclusive Bottlers In Malta and Gozo for The Kitty-Kola Co. Ltd., London 165/6 FLEUR-DE-LYS, BIRKIRKARA£MALTA Malta’s First-class Mineral Water Manufacturers OUR SPECIALITY—THE FOLLOWING SOFT DRINKS PINEAPPLE LEMONADE ORANGE GINGER BEER i f GRAPE FRUIT i f DRY GINGER i f STRAWBERRY TONIC WATER LIME JUICE SODA WATER Suppliers for N.A.A.F.I., Malta When you are serving in Malta, afloat or ashore, always call for ★ STAR’S* REFRESHERS * AND SEE THAT YOU GET THEM ********************************************* A JOB ASSURED BEFORE you leave the Services is encouraging. I SHORT BROTHERS HARLAN D* LIMITED have the jobs. Have you the qualifications ? ---------------------------------------------------- • W e need EN GIN EERS and TECHNICAL ASSISTANTS with University Degrees. National Certificates or the equivalent, for development work on aircraft, servo-mechanisms, guided missiles, auto-pilots and electronic and hydraulic research, in short, men qualified in mechanical or electrical engineering, mathematics, physics and with experience or an interest In aircraft and in related matters. To such as these we can offer a satisfactory career. If you are interested why not talk it over when you are on leave. Apply giving educational background to: STAFF APPOINTMENTS OFFICER, P.O. BO X 241, BELFAST, quoting S.A. 92. THE COMMUNICATOR 1 /»•<»#*I# in touch withm u r p h y ' I I Lo o L n - ~ _ J^ = > O /*=» <=* j O >V Our Admiralty Type 618 Marine Communications Equipment meets the needs of all kinds of ships. It consists of an M.F./H.F. -

Nuclear Proliferation: a Civilian and a Military Dilemma Nuclear Proliferation: a C Ivilian and a Military D Ilemma

ilemma D NUCLEAR PROLIFERATION: ivilian and a Military A CIVILIAN AND A MILITARY DILEMMA C A Nuclear Proliferation: The danger of nuclear proliferation is growing in proportion to weapons stockpiles, reversing Pyongyang’s nuclear buildup, and the number of new nuclear power stations all over the world. stopping Iran’s nuclear weapons-related activities. The hope There is no insurmountable division between the civil and mili- is that each of these efforts will be mutually reinforcing and tary use of this technology in spite of the efforts on the part of that progress in reducing existing nuclear weapons will per- the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to regulate suade the world’s nonnuclear weapons states to do more to stay this. The most recent example is Iran. At the end of the day clear of dangerous civilian nuclear fuel-making activities. This anyone who does not want to be regulated cannot be forced to set of nuclear hopes, however, is unlikely to be fully realised. do so. With the expansion of nuclear energy there is a grow- Barring regime change in either North Korea or Iran, neither ing necessity to build reprocessing plants and fast breeders in Pyongyang’s renunciation of its nuclear arsenal nor Iran’s ces- order to produce nuclear fuel. Both give rise to the circulation sation of nuclear weapons-related activities is all that probable. of plutonium leading in turn to the creation of huge amounts of Meanwhile, the odds of China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, fissile material capable of making bombs – a horror scenario! and Israel agreeing to nuclear warhead reductions seem even With the run-up to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) more remote. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Nuclear Warheads

OObservatoire des armes nucléaires françaises The Observatory of French Nuclear Weapons looks forward to the elimination of nuclear weapons in conformity with the aims of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. To that end, the Observatory disseminates follow-ups of information in the forms of pamphlets and entries on the World Wide Web: • on the evolution of French nuclear forces; • on the on-going dismantling of nuclear sites, weapons, production facilities, and research; • on waste management and environmental rehabilitation of sites; • on French policy regarding non-proliferation; • on international cooperation (NGO’s, international organizations, nations), toward the elimination of nuclear weapons; • on the evolution of the other nuclear powers’ arsenals. The Observatory of French Nuclear Weapons was created at the beginning of the year 2000 within the Center for Documentation and Research on Peace and Conflicts (CDRPC). It has received support from the W. Alton Jones Foundation and the Ploughshares Fund. C/o CDRPC, 187 montée de Choulans, F-69005 Lyon Tél. 04 78 36 93 03 • Fax 04 78 36 36 83 • e-mail : [email protected] Site Internet : www.obsarm.org Dépôt légal : mai 2001 - 1ère édition • édition anglaise : novembre 2001 ISBN 2-913374-12-3 © CDRPC/Observatoire des armes nucléaires françaises 187, montée de Choulans, 69005 Lyon (France) Table of contents The break-down of nuclear disarmament ....................................................................................................................................... 5 The -

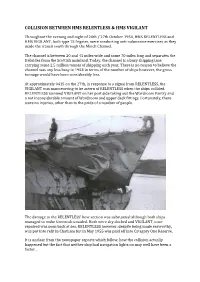

Collision Between Hms Relentless & Hms Vigilant

COLLISION BETWEEN HMS RELENTLESS & HMS VIGILANT Throughout the evening and night of 26th / 27th October 1954, HMS RELENTLESS and HMS VIGILANT, both type 15 frigates, were conducting anti-submarine exercises as they made the transit south through the Minch Channel. The channel is between 20 and 45 miles wide and some 70 miles long and separates the Hebrides from the Scottish mainland. Today, the channel is a busy shipping lane carrying some 2.5 million tonnes of shipping each year. There is no reason to believe the channel was any less busy in 1954 in terms of the number of ships however, the gross tonnage would have been considerably less. At approximately 0415 on the 27th, in response to a signal from RELENTLESS, the VIGILANT was manoeuvring to be astern of RELENTLESS when the ships collided. RELENTLESS rammed VIGILANT on her port side taking out the Wardroom Pantry and a not inconsiderable amount of Wardroom and upper deck fittings. Fortunately, there were no injuries, other than to the pride of a number of people. The damage to the RELENTLESS’ bow section was substantial although both ships managed to make Greenock unaided. Both were dry docked and VIGILANT, once repaired was soon back at sea. RELENTLESS however, despite being made seaworthy, was put into refit in Chatham but in May 1955 was paid off into Category One Reserve. It is unclear from the newspaper reports which follow, how the collision actually happened but the fact that neither ship had navigation lights on may well have been a factor... The Glasgow Herald, Saturday December 4th 1954. -

Assemblée Nationale Constitution Du 4 Octobre 1958

N° 260 —— ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE CONSTITUTION DU 4 OCTOBRE 1958 DOUZIÈME LÉGISLATURE Enregistré à la Présidence de l'Assemblée nationale le 10 octobre 2002. AVIS PRÉSENTÉ AU NOM DE LA COMMISSION DE LA DÉFENSE NATIONALE ET DES FORCES ARMÉES, SUR LE PROJET DE loi de finances pour 2003 (n° 230) TOME II DÉFENSE DISSUASION NUCLÉAIRE PAR M. ANTOINE CARRE, Député. —— Voir le numéro : 256 (annexe n° 40) Lois de finances. — 3 — S O M M A I R E _____ Pages INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 5 I. — UNE DISSUASION GARDANT UNE PLACE CENTRALE DANS LES STRATEGIES DE DEFENSE, MAIS DONT LE ROLE EVOLUE........................................................................................ 7 A. LA DISSUASION NUCLEAIRE AMERICAINE : UNE VOLONTE DE FLEXIBILITE ACCRUE .................................................................................................................................... 7 B. UNE INQUIETANTE PROLIFERATION BALISTIQUE ET NUCLEAIRE ................................... 10 C. LA DISSUASION NUCLEAIRE FRANÇAISE : UNE POSTURE ADAPTEE A L’EVOLUTION DE LA MENACE .............................................................................................. 15 1. Une dissuasion nécessaire pour faire face à l’imprévisible ........................................ 15 2. Un outil d’ores et déjà adapté ......................................................................................... 16 II. — UN BUDGET 2003 PERMETTANT LA POURSUITE DE LA MODERNISATION -

Chasing Success

AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE Chasing Success Air Force Efforts to Reduce Civilian Harm Sarah B. Sewall Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dr. Ernest Allan Rockwell Sewall, Sarah B. Copy Editor Carolyn Burns Chasing success : Air Force efforts to reduce civilian harm / Sarah B. Sewall. Cover Art, Book Design and Illustrations pages cm L. Susan Fair ISBN 978-1-58566-256-2 Composition and Prepress Production 1. Air power—United States—Government policy. Nedra O. Looney 2. United States. Air Force—Rules and practice. 3. Civilian war casualties—Prevention. 4. Civilian Print Preparation and Distribution Diane Clark war casualties—Government policy—United States. 5. Combatants and noncombatants (International law)—History. 6. War victims—Moral and ethical aspects. 7. Harm reduction—Government policy— United States. 8. United States—Military policy— Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title. II. Title: Air Force efforts to reduce civilian harm. UG633.S38 2015 358.4’03—dc23 2015026952 AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Director and Publisher Allen G. Peck Published by Air University Press in March 2016 Editor in Chief Oreste M. Johnson Managing Editor Demorah Hayes Design and Production Manager Cheryl King Air University Press 155 N. Twining St., Bldg. 693 Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6026 [email protected] http://aupress.au.af.mil/ http://afri.au.af.mil/ Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the organizations with which they are associated or the views of the Air Force Research Institute, Air University, United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or any AFRI other US government agency. -

Ballistic, Cruise Missile, and Missile Defense Systems: Trade and Significant Developments, June 1994-September 1994

Missile Developments BALLISTIC, CRUISE MISSILE, AND MISSILE DEFENSE SYSTEMS: TRADE AND SIGNIFICANT DEVELOPMENTS, JUNE 1994-SEPTEMBER 1994 RUSSIA WITH AFGHANISTAN AND AFGHANISTAN TAJIKISTAN AUSTRALIA 8/10/94 According to Russian military forces in Dushanbe, the 12th post of the Moscow INTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS border troops headquarters in Tajikistan is INTERNAL DEVELOPMENTS attacked by missiles fired from Afghan ter- 9/27/94 ritory. The Russians respond with suppres- 7/94 Rocket and mortar attacks leave 58 people sive fire on the missile launcher emplace- It is reported that Australia’s University of dead and 224 wounded in Kabul. Kabul ment; no casualties are reported. Queensland can produce a scramjet air- radio attributes this attack to factions op- Itar-Tass (Moscow), 8/11/94; in FBIS-SOV-94-155, breathing engine, which may offer payload posing President Burhanuddin Rabbani. 8/11/94, p. 36 (4564). and cost advantages over conventional SLVs. More than 100 rockets and mortar shells Chris Schacht, Australian (Sydney), 7/20/94, p. 6; are fired on residential areas of Kabul by 8/27/94 in FBIS-EAS-94-152, 8/8/94, pp. 89-90 (4405). anti-Rabbani militia under the control of During the early morning hours, Tajik Prime Minister Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Mujaheedin launch several missiles at the 7/94 northern warlord General Abdul Rashid Russian Frontier Guard observation posi- It is reported that the Australian government Dostam. tion and post on the Turk Heights in awarded Australia’s AWA Defence Industries Wall Street Journal, 9/28/94, p. 1 (4333). Tajikistan. The missiles are launched from (AWADI) a $17 million contract to produce the area of the Afghan-Tajik border and from the Active Missile Decoy (AMD) system, a Afghan territory, according to the second “hovering rocket-propelled anti-ship missile commander of Russian border guards in decoy system” providing for ship defense against sea-skimming missiles.