Challenges of Volunteer Management in Kazakhstan*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worrying Levels of HIV Prevalence in Blood Donations in Eastern Europe

Worrying levels of HIV prevalence EuroTB and EuroHIV are supported by the European Commission (DG-SANCO) in blood donations in eastern Europe Giedrius Likatavicius 12, rue du Val d’Osne - 94415 St-Maurice Cedex - FRANCE Tél. : 33 (0)1 41 79 68 68 Fax : 33 (0)1 41 79 68 02 [email protected] Giedrius Likatavicius, Angela M. Downs, Françoise F. Hamers MoPeC3574 Institut de veille sanitaire, Saint-Maurice, France In the West, HIV prevalence among blood donations fell sharply during 1986-1988, from 18 to Background 8 per 100,000 donations, then decreased steadily to 1.4 in 2001 and is now very low: overall, 1.3 per 100 000 donations in 2002. However, levels of over 2 per 100 000 have been reported in almost all of the countries during the last 5 years: from Italy (between 2 and 5 per 100 000), Greece (5-7), Throughout Europe, blood donations are systematically screened for HIV antibodies and donations Portugal (10-18, but data are provided only from regional blood centres in three large cities and which test positive are eliminated from the blood supply. Nevertheless, a small residual risk of HIV do not represent the country as a whole) and Spain (4-7). infection through transfusion of undetected infected blood remains; the higher the incidence and thus the prevalence of HIV among blood donors, the higher the residual risk. Monitoring HIV prevalence Available data on donations from new and repeat donors (14 countries from the West and 5 from the among donations provides an indication of the relative safety of the blood supply between countries centre ) continue to show consistently higher (10 times) prevalence levels among new donors and and over time. -

Mr. Ms. First Name FAMILY NAME Section Or Unit/Title/Position/Rank

Mr. First Name FAMILY NAME Section or Unit/Title/Position/Rank Ms. DELEGATIONS ALBANIA Albania Mr. Alqiviadhi PULI Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Albania Mr. Spiro KOÇI Ambassador, Permanent Representative Albania Ms. Ravesa LLESHI Advisor Albania Mr. Glevin DERVISHI Advisor Albania Mr. Xhodi SAKIQI Counsellor GERMANY Germany Dr. Guido WESTERWELLE Minister Germany Mr. Rüdiger LÜDEKING Ambassador, Head of Permanent Mission to the OSCE Germany Mr. Juergen SCHULZ Deputy Political Director Germany Mr. Thomas OSSOWSKI Deputy Head of Minister’s Office Germany Mr. Martin SCHÄFER Deputy Federale Foreign Office Spokesperson Germany Mr. Thomas Eberhard SCHULTZE Head of OSCE Division Germany Ms. Christine WEIL Deputy Head of Permanent Mission to the OSCE Germany Mr. Hans-Henning PRADEL Senior Military Adviser Germany Mr. Steffen FEIGL Bagage Master Germany Mr. Bernd PFAFFENBACH Military Adviser Germany Ms. Heike JANTSCH Counsellor Germany Mr. Detlef HEMPEL Military Adviser Germany Mr. Holger LEUKERT Desk Officer Ministry of Defence Germany Ms. Anne DR. WAGNER-MITCHELL Counsellor Germany Mr. Jean P. FROEHLY Counsellor Germany Mr. Julian LÜBBERT First Secretary Germany Ms. Annette PÖLKING First Secretary Germany Mr. Anna SCHRÖDER First Secretary Germany Mr. Stephan FAGO Second Secretary Germany Ms. Anna-Elisabeth VOLLERT Assistant Attacheé Germany Mr. Sören HEINE Assistent Senior Military Adviser Germany Mr. Joerg Emil GAUDIAN Protocol desk officer Germany Mr. Bruno WOBBE Communication Germany Mr. Thomas KÖHLER Official Fotograph Germany Mr. Christof WEIL Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Germany Ms. Anka FELDHUSEN Minister Counsellor and Deputy Head of Mission Germany Ms. Daniela BERGELT First Secretary Germany Mr. Christopher FUCHS First Secretary Germany Ms. Tanja BEYER First Secretary Germany Mr. -

ALPAMYSH Central Asian Identity Under Russian Rule

ALPAMYSH Central Asian Identity under Russian Rule BY H. B. PAKSOY Association for the Advancement of Central Asian Research Monograph Series Hartford, Connecticut First AACAR Edition, 1989 --------- ALPAMYSH: Central Asian Identity under Russian Rule COPYRIGHT 1979, 1989 by H. B. PAKSOY All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Paksoy, H. B., 1948- ALPAMYSH: central Asian identity under Russian rule. (Association for the Advancement of Central Asian Research monograph series) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) Includes index. 1. Soviet Central Asia--History--Sources. 2. Alpamish. 3. Epic Literature, Turkic. 4. Soviet Central Asia--Politics and Government. I. Title. II. Series. DK847.P35 1989 958.4 89-81416 ISBN: 0-9621379-9-5 ISBN: 0-9621379-0-1 (pbk.) AACAR (Association for the Advancement of Central Asian Research) Monograph Series Editorial Board: Thomas Allsen (TRENTON STATE COLLEGE) (Secretary of the Board); Peter Golden (RUTGERS UNIVERSITY); Omeljan Pritsak (HARVARD UNIVERSITY); Thomas Noonan (UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA). AACAR is a non-profit, tax-exempt, publicly supported organization, as defined under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, incorporated in Hartford, Connecticut, headquartered at the Department of History, CCSU, 1615 Stanley Street, New Britain, CT 06050. The Institutional Members of AACAR are: School of Arts and Sciences, CENTRAL CONNECTICUT STATE UNIVERSITY; Nationality and Siberian Studies Program, The W. Averell Harriman Institute for the Advanced Study of the Soviet Union, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY; Mir Ali Shir Navai Seminar for Central Asian Languages and Cultures, UCLA; Program for Turkish Studies, UCLA; THE CENTRAL ASIAN FOUNDATION, WISCONSIN; Committee on Inner Asian and Altaistic Studies, HARVARD UNIVERSITY; Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, INDIANA UNIVERSITY; Department of Russian and East European Studies, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA; THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH, WASHINGTON D.C. -

Final List of Participants 22 Ministerial Council Meeting 3

MC.INF/11/15/Rev.3 4 December 2015 ENGLISH only FINAL LIST OF PARTICIPANTS 22nd MINISTERIAL COUNCIL MEETING 3 - 4 December 2015 Belgrade Serbia Belgrade, 4 December 2015 2nd Ministerial Council Meeting, 3 - 4 December 2015, BELGRADE DELEGATION NAME SURNAME FUNCTION PARTICIPATING STATES ALBANIA DITMIR BUSHATI MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS ALBANIA ROLAND BIMO AMBASSADOR ALBANIA ILIR BOCKA AMBASSADOR ALBANIA PIRRO VENGU HEAD OF MINISTER'S CABINET ALBANIA RAVESA LLESHI ADVISER ALBANIA GLEVIN DERVISHI ADVISER ALBANIA ARTAN CANAJ DEPUTY HEAD OF MISSION TO OSCE ALBANIA XHELAL FEJZA COUNCELLOR, EMBASSY OF ALBANIA IN BELGRADE ALBANIA VIRGJIL MUÇI COUNSELLOR ALBANIA ARBEN ZANI MILITARY ADVISER, PERMANENT MISSION TO OSCE ALBANIA ŠANI FEJZI DRIVER GERMANY FRANK-WALTER STEINMEIER FOREIGN MINISTER SPECIAL REPRESENTATIVE OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT FOR THE OSCE GERMANY GERNOT ERLER CHAIRMANSHIP GERMANY EBERHARD POHL AMBASSADOR HEAD OF MISSION DEPUTY SPECIAL REPRESENTATIVE OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT FOR THE GERMANY ANTJE LEENDERTSE OSCE CHAIRMANSHIP AND HEAD OF OSCE TASK FORCE AMBASSADOR, DESIGNATED SPECIAL REPRESENTATIVE OF THE CIO FOR THE GERMANY CORD HINRICH MEIER-KLODT TRANSDNIESTRIAN SETTLEMENT PROCESS GERMANY AXEL WILHELM DITTMANN HEAD OF MISSION GERMANY SIBYLLE KATHARINA SORG DEPUTY HEAD OF MINISTER´S OFFICE GERMANY MARTIN SCHÄFER SPOKESPERSON GERMANY SAWSAN CHEBLI DEPUTY SPOKESPERSON, FFO HEAD OF DIVISION CONVENTIONAL ARMS CONTROL ANS CSBM IN OSCE AREA, GERMANY CLARISSA DUVIGNEAU FEDERAL FOREIGN OFFICE GERMANY HANS-ULRICH SÜDBECK HEAD OF DIVISION, -

List of Delegations to the Seventieth Session of the General Assembly

UNITED NATIONS ST /SG/SER.C/L.624 _____________________________________________________________________________ Secretariat Distr.: Limited 18 December 2015 PROTOCOL AND LIAISON SERVICE LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE SEVENTIETH SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY I. MEMBER STATES Page Page Afghanistan......................................................................... 5 Chile ................................................................................. 47 Albania ............................................................................... 6 China ................................................................................ 49 Algeria ................................................................................ 7 Colombia .......................................................................... 50 Andorra ............................................................................... 8 Comoros ........................................................................... 51 Angola ................................................................................ 9 Congo ............................................................................... 52 Antigua and Barbuda ........................................................ 11 Costa Rica ........................................................................ 53 Argentina .......................................................................... 12 Côte d’Ivoire .................................................................... 54 Armenia ........................................................................... -

Political Party Regulation Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul

Guidelines on Political Party Regulation Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) ul. Miodowa 10 00-251 Warsaw Poland www.osce.org/odihr © OSCE/ODIHR 2011 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the OSCE/ODIHR and the Venice Commis- sion as the sources. ISBN 978-92-9234-804-5 Designed by Homework, Warsaw, Poland Printed in Poland by POLIGRAFUS Jacek Adamiak Guidelines on Political Party Regulation Adopted by the Venice Commission at its 84th Plenary Session Venice, 15–16 October 2010 Warsaw/Strasbourg 2011 Contents Foreword. 9 Legislative Support: ODIHR and the Venice Commission ................ 11 Acknowledgements .......................................... 13 Introduction (§1–8) .......................................... 15 Definition of “Political Party” (§9) ................................ 18 The Importance of Political Parties (§10) ............................ 18 Fundamental Rights Given to Political Parties (§11) .................... 19 SECTION A. Guidelines Pertaining to Political Parties ............ 20 Principles (§12–13) ........................................... 21 Principle 1. Right of Individuals to Associate (§14) Principle 2. The State’s Duty to Protect the Individual Right of Free Association (§15) Principle 3. Legality (§16) Principle 4. Proportionality (§17) Principle 5. Non-discrimination (§18) Principle 6. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 150 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 17, 2004 No. 34 Senate The Senate was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Monday, March 22, 2004, at 12 noon. House of Representatives WEDNESDAY, MARCH 17, 2004 The House met at 10 a.m. and was THE JOURNAL dren are going to newly renovated called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The schools. Decades of neglect by Saddam pore (Mr. BASS). Chair has examined the Journal of the are being reversed in record time as health clinics, water sources, elec- f last day’s proceedings and announces to the House his approval thereof. tricity and sanitation are being re- DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- stored throughout the country. PRO TEMPORE nal stands approved. Most importantly, the world no longer lives under the constant threat f The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- of a madman who harbored and sup- fore the House the following commu- PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ported terrorists. nication from the Speaker: The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the After World War II, we helped rebuild WASHINGTON, DC, gentleman from Texas (Mr. Germany to assist it from becoming a March 17, 2004. NEUGEBAUER) come forward and lead breeding ground for communists, and I hereby appoint the Honorable CHARLES F. we were successful. Today we are re- BASS to act as Speaker pro tempore on this the House in the Pledge of Allegiance. -

Space, Image and Display in Russian Central Asia, 1881

SPACE, IMAGE AND DISPLAY IN RUSSIAN CENTRAL ASIA, 1881-1914 Jennifer Mary Keating UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Declaration I, Jennifer Mary Keating, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ---------------------------------- --------------------------------- 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the relationship between environment and empire in late tsarist Central Asia, and suggests that the making and unmaking of space was integral to the imperial experience. It contends that land and its representation were crucial to processes undertaken on local and imperial scales to re-fashion parts of Central Asia from a ‘vast’, ‘alien’ and ‘inhospitable’ colony into an integrated frontier of empire. In examining the environment as a site for the physical enactment and negotiation of Russian rule, the chapters investigate how imperial settlers interacted with the region’s built and natural landscapes, through the planning of transport routes, the creation of settlements, irrigation, afforestation and planting projects. I use visual sources as the project’s access points into the Russian spatial imaginary: vital interfaces between material and metaphorical space that documented the changing environment but were also used to project future ambitions, to inscribe meaning, and to appropriate, segregate, contest and re- order terrain. Environment, image and the spatial imagination were entwined in a symbiotic relationship, with attempts to modify Central Asia’s landscapes, and the visual representations of these actions, revealing that the concept of Turkestan as a monolithic colonial space underwent significant fragmentation. -

Pdf Doc/05.Pdf (Accessed: 9.02.2019)

№ 1 (21) ▪ 2020 ▪ April Russian Linguistic Bulletin ISSN 2303-9868 PRINT ISSN 2227-6017 ONLINE Yekaterinburg 2020 RUSSIAN LINGUISTIC BULLETIN ISSN 2313-0288 PRINT ISSN 2411-2968 ONLINE Theoretical and scientific journal. Published 4 times a year. Founder: Sokolova M.V. Editor in chief: Smirnova N.L., PhD Publisher and editorial address: Yekaterinburg, Akademicheskaya St., Bldg. 11A, office 4, 620137, Russian Federation Email: [email protected] Website: www.rulb.org 16+ Publication date 16.04.2020 № 1 (21) 2020 Signed for printing 11.04.2020 April Circulation 100 copies. Price: free. Order # 201950. Printed from the original layout. Printed by "A-Print" typography 620049, Yekaterinburg, Ln. Lobachevskogo, Bldg. 1. Russian Linguistic Bulletin is a peer-reviewed scholarly journal dedicated to the questions of linguistics, which provides an opportunity to publish scientific achievements to graduate students, university professors, persons with a scientific degree, public figures, figures of culture, education and politicians from the CIS countries and around the world. The journal is an open access journal which means that everybody can read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles in accordance with CC Licence type: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Certificate number of registration in the Federal Supervision Service in the Sphere of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Communications: ПИ № ФС 77 – 58339, ЭЛ № ФС 77 – 73011 Editorial board: Rastjagaev A.V. PhD in Philology, Moscow City University (Moscow, Russia) Slozhenikina Ju.V. PhD in Philology, Moscow City University (Moscow, Russia) Shtreker N.Ju. PhD in Pedagogy, PhD in Philology, Kaluga State Pedagogical University (Kaluga, Russia) Levickij A.Je. -

Eighth United Nations Conference to Review All Aspects of the Set Of

United Nations TD/RBP/CONF.9/INF.1 United Nations Conference Distr.: General 10 June 2021 on Trade and Development English/French/Spanish only Eighth United Nations Conference to Review All Aspects of the Set of Multilaterally Agreed Equitable Principles and Rules for the Control of Restrictive Business Practices Geneva, 19–23 October 2020 List of participants GE.21-07682(E) TD/RBP/CONF.9/INF.1 Members Albania Ms. Juliana Latifaj, Chair, Competition Authority, Tirana Ms. Diana Dervishi, General Secretary, Competition Authority, Tirana Algeria M. Amara Zitouni, Président, Conseil de la concurrence, Algérie Mr. Djilali Slimani, Permanent Member, Competition Council, Algeria Mr. Mourad Boukadoum, Minister Plenipotentiary, Mission Permanente, Geneva Mme Aicha Kaloune Eps Zenati, Inspecteur principale, Ministère du Commerce, Alger Argentina Sr. Sergio Sebastián Barocelli, Director Nacional de Defensa del Consumidor, Dirección Nacional de Defensa del Consumidor, Buenos Aires Sr. Eduardo Aracil, Asesor Jurídico, Comisión Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia, Buenos Aires Sra. Balbina Griffa, Vocal, Comisión Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia, Buenos Aires Sr. Pablo Lepere, Comisionado, Comisión Nacional de Defensa de la Competencia, Buenos Aires Sra. María Cecilia Lotto, Abogada, Asesora RRII, Dirección Nacional de Defensa del Consumidor, Buenos Aires, Argentina Sr. Matías Ninkov, Primer Secretario, Misión Permanente, Ginebra Armenia Mr. Gegham Gevorgyan, Chair, State Commission for the Protection of Economic Competition, Yerevan Mr. Hayk Karapetyan, Member, State Commission for the Protection of Economic Competition, Yerevan Ms. Shushan Sargsyan, Head of Legal Department, State Commission for the Protection of Economic Competition, Yerevan Mr. Henrik Yeritsyan, Third Secretary, Permanent Mission, Geneva Australia Mr. Rod Sims, Chair, Competition and Consumer Commission of Australia, Sydney Ms. -

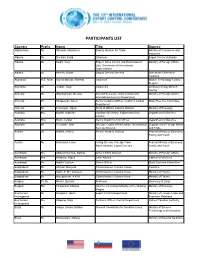

13Th International Export Control Conference Participants List.Pdf

PARTICIPANTS LIST Country Prefix Name Title Agency Afghanistan Mr. Shinwari, Mozammil Deputy Minister for Trade Ministry of Commerce and Industries Albania Mr. Dervishi, Erald Chairman Export Control Authority Albania Mr. Kodra, Gert Expert, Arms Control and Disarmament Ministry of Foreign Affairs Unit, Directorate of International Organizations Albania Mr. Merlika, Qazim Deputy Director-General Directorate General of Customs Argentina H.E. Amb. García Moritán, Roberto Chairman Missile Technology Control Regime Argentina Mr. Jordan, Jorge Counsellor Embassy of Argentina in Vienna Armenia Mr. Gharibjanyan, Gevorg Second Secretary, Arms Control and Ministry of Foreign Affairs International Security Department Armenia Mr. Karapetyan, Artem Senior Customs Officer, Customs Control State Revenue Committee Department Armenia Mr. Petrosyan, Tigran Head of Military Industry Division Ministry of Economy Australia Ms. Burrell, Gabrielle Assistant Secretary, Export and Arms Department of Defence Control Australia Mrs. Nixon, Lyndal Senior Export Control Officer Department of Defence Australia Mr. Tilemann, John Director, Counter Proliferation, International Department of Foreign Affairs Security Division and Trade Austria Dr. Krehlik, Helmut Former Head of Division Federal Ministry of Economy, Family and Youth Austria Mr. Schramml, Hans Acting Director, Foreign Trade Federal Ministry of Economy, Administration, Export Controls Family and Youth Azerbaijan Ms. Abdurahmanova, Nahida Arms Control Division Ministry of Foreign Affairs Azerbaijan Mrs. Asadova, Aygun Chief Advisor Cabinet of Ministers Azerbaijan Mr. Najafli, Jeyhun Senior Officer State Customs Committee Bangladesh Mr. Ahmed, Margoob Commissioner, Custom House Customs Bangladesh Mr. Kabir, S. M. Humayun Commissioner, Custom House Ministry of Finance Bangladesh Mr. Nuruzzaman, A K M Commissioner, Custom House Ministry of Finance Belgium Pr. Dr. Michel, Quentin Professor University of Liège Belgium Ms. -

Annual Activity Report, 2018

Annual Activity Report, 2018 OECD-GVH Regional Centre for Competition in Budapest (Hungary) Gazdasági Versenyhivatal Contact: Andrea Dalmay OECD-GVH Regional Centre for Competition in Budapest (Hungary) Gazdasági Versenyhivatal (GVH) Hungarian Competition Authority H-1391 Budapest 62, POBox 211 Hungary Phone: (+36-1) 472-8880 Fax: (+36-1) 472-8898 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.oecdgvh.org illustration: Starline - Freepik.com I. Introduction and organisational setup The OECD-GVH Regional Centre for Competition in the CIS countries, namely Albania, Armenia, Azer- Budapest (Hungary) (“RCC”) was established by the baijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Gazdasági Versenyhivatal (GVH, Hungarian Compe- Croatia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo*, Kyrgyzstan, tition Authority) and the Organisation for Econom- North Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, ic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on 16 Feb- the Russian Federation, Serbia and Ukraine. The ruary 2005 when a Memorandum of Understanding work targeting these economies is regarded as the was signed by the parties. core activity of the RCC. These economies have all progressed with the development of their competi- The main objective of the RCC is to foster the devel- tion laws and policies, but are at different stages in opment of competition policy, competition law and this process. As a consequence, the needs for capac- competition culture in the South-East, East and Cen- ity building differ among the involved non-OECD tral European regions and to thereby contribute