Words and Worlds:<Br>Dada and the Destruction of <I>Logos</I>, Zurich 1916

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Authenticity of Ambiguity: Dada and Existentialism

THE AUTHENTICITY OF AMBIGUITY: DADA AND EXISTENTIALISM by ELIZABETH FRANCES BENJAMIN A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham August 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ii - ABSTRACT - Dada is often dismissed as an anti-art movement that engaged with a limited and merely destructive theoretical impetus. French Existentialism is often condemned for its perceived quietist implications. However, closer analysis reveals a preoccupation with philosophy in the former and with art in the latter. Neither was nonsensical or meaningless, but both reveal a rich individualist ethics aimed at the amelioration of the individual and society. It is through their combined analysis that we can view and productively utilise their alignment. Offering new critical aesthetic and philosophical approaches to Dada as a quintessential part of the European Avant-Garde, this thesis performs a reassessment of the movement as a form of (proto-)Existentialist philosophy. The thesis represents the first major comparative study of Dada and Existentialism, contributing a new perspective on Dada as a movement, a historical legacy, and a philosophical field of study. -

Before Zen: the Nothing of American Dada

Before Zen The Nothing of American Dada Jacquelynn Baas One of the challenges confronting our modern era has been how to re- solve the subject-object dichotomy proposed by Descartes and refined by Newton—the belief that reality consists of matter and motion, and that all questions can be answered by means of the scientific method of objective observation and measurement. This egocentric perspective has been cast into doubt by evidence from quantum mechanics that matter and motion are interdependent forms of energy and that the observer is always in an experiential relationship with the observed.1 To understand ourselves as in- terconnected beings who experience time and space rather than being sub- ject to them takes a radical shift of perspective, and artists have been at the leading edge of this exploration. From Marcel Duchamp and Dada to John Cage and Fluxus, to William T. Wiley and his West Coast colleagues, to the recent international explosion of participatory artwork, artists have been trying to get us to change how we see. Nor should it be surprising that in our global era Asian perspectives regarding the nature of reality have been a crucial factor in effecting this shift.2 The 2009 Guggenheim exhibition The Third Mind emphasized the im- portance of Asian philosophical and spiritual texts in the development of American modernism.3 Zen Buddhism especially was of great interest to artists and writers in the United States following World War II. The histo- ries of modernism traced by the exhibition reflected the well-documented influence of Zen, but did not include another, earlier link—that of Daoism and American Dada. -

LA CLASE Tema Del Mes

LA CLASE Tema del mes Escenas dadás Dada 1916-2016 Mercadillo de revistas Dada (II) Esta última serie va dedicada a los editores de publicaciones periódicas dadaístas que iremos distribuyendo en varios grupos, (la anterior correspondía a Alemania, Suiza y Holanda, en esta hay restos de Alemania, Usa, Serbia…) y que esperemos sea el final de todas las series de fotomontajes. Encuentro de editores de publicaciones DADA (II), en primer lugar de pie Walter Serner, que viene de visita y ha dejado una pila de libros encima de la mesa, el de arriba “Letzte Lockerung: Manifest Dada” (Ultima relajación: Manifiesto Dada), traducido aquí como Pálido punto de luz Claroscuros en la educación http://palido.deluz.mx Número 65. (Febrero, 2016) Dadaísmo y educación:Absurdos centenarios y actuales Manual para embaucadores (o aquellos que quieran llegar a serlo). Y ahora sí de izquierda a derecha, la publicación entre paréntesis: Wilhelm Uhde (Die Freude), Malcon Cowley (Aesthete 1925), Paul Rosenfeld (MSS), Henri-Pierre Roché y Beatrice Wood (Blindman), Hans Goltz (Der Ararat), detrás en la puerta; Ljubomir Micic (Zenit) y Serge Charchoune (Perevoz Dada). Mercadillo de revistas Dada (I) Esta última serie va dedicada a los editores de publicaciones periódicas dadaístas, que iremos distribuyendo en varios grupos, y que esperemos sea el final de todas las series de fotomontajes. Encuentro de editores de publicaciones DADA (I), de izquierda a derecha, la publicación entre paréntesis: F.W. Wagner (Der Zweemann), Walter Hasenclever (Menschen), Friedrich Hollaender (Neue Jugend), Theo van Doensburg —de pie— (De Stijl y Mecano), Hans Richter ( G), detrás de él al lado de la puerta; John Heartfield, Wieland Herzfelde y George Grosz (Die Pleite y Jedermann sein eigener Fussball), al lado de Richter, Kurt Schwitters (Merz), Raoul Hausmann (Der Dada y Freie Strasse), Pálido punto de luz Claroscuros en la educación http://palido.deluz.mx Número 65. -

Jews in Dada: Marcel Janco, Tristan Tzara, and Hans Richter

1 Jews in Dada: Marcel Janco, Tristan Tzara, and Hans Richter This lecture deals with three Jews who got together in Zurich in 1916. Two of them, Janco and Tzara, were high school friends in Romania; the third, Hans Richter, was German, and, probably unbeknown to them, also a Jew. I start with Janco and I wish to open on a personal note. The 'case' of Marcel Janco would best be epitomized by the somewhat fragmented and limited perspective from which, for a while, I was obliged to view his art. This experience has been shared, fully or in part, by my generation as well as by those closer to Janco's generation, Romanians, Europeans and Americans alike. Growing up in Israel in the 1950s and 60s, I knew Janco for what he was then – an Israeli artist. The founder of the artists' colony of Ein Hod, the teacher of an entire generation of young Israeli painters, he was so deeply rooted in the Israeli experience, so much part of our landscape, that it was inconceivable to see him as anything else but that. When I first started to read the literature of Dada and Surrealism, I was surprised to find a Marcel Janco portrayed as one of the originators of Dada. Was it the same Marcel Janco? Somehow I couldn't associate an art scene so removed from the mainstream of modern art – as I then unflatteringly perceived 2 the Israeli art scene – with the formidable Dada credentials ascribed to Janco. Later, in New York – this was in the early 1970s – I discovered that many of those well-versed in the history of Dada were aware of Marcel Janco the Dadaist but were rather ignorant about his later career. -

From Dada to Dank Memes: Revolt, Revulsion, and Discontent Theocrit 9152-001 Dr

FROM DADA TO DANK MEMES: REVOLT, REVULSION, AND DISCONTENT THEOCRIT 9152-001 DR. ANDREW WENAUS Fall 2018 Lecture: Tuesday 9:30am-12:30pm Location: STVH 3165 Office hours: Tuesday: 1:00pm-3:00pm Office: UC 1421 Email: [email protected] Course Description: This course examines the complex trajectory of Dadaism as it continues to resonate both with and against our present political and cultural climate. Early twentieth-century avant-garde art shifted from an ethos of art for art’s sake to art as lived experience and revolutionary gesture. Dada was motivated by disgust towards the political and social establishment of its time. Rather than inspired by an individual’s spontaneous overflow of pathos, the quintessential Dadaist poem is an arbitrary re- assemblage of already-available text and images. For Dadaists, not only does this approach to art change a life, it also responds to changes in Modern life. Yet, this reimagining of the empirical and political self as an already-constituted “automated self” proves to be a challenge to artistic and public life to this day. From the collage of Max Ernst’s proto-graphic novel Une Semaine de Bonté (1934) to the cut-up experiments of William S. Burroughs, Brion Gysin, and J.G. Ballard in the 1950s and 1960s to the remix fiction of Kathy Acker and Jeff Noon in the 1980s and 1990s, there is an emphasis on how ready-made and re-arranged text/image is both constituting and constructive. These practices are expressed as liberating; digital technology makes these processes widely accessible and practically limitless. -

Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection

Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection... Page 1 of 26 Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection IRENE E. HOFMANN Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago Dada 6 (Bulletin The Mary Reynolds Collection, which entered The Art Institute of Dada), Chicago in 1951, contains, in addition to a rich array of books, art, and ed. Tristan Tzara ESSAYS (Paris, February her own extraordinary bindings, a remarkable group of periodicals and 1920), cover. journals. As a member of so many of the artistic and literary circles View Works of Art Book Bindings by publishing periodicals, Reynolds was in a position to receive many Mary Reynolds journals during her life in Paris. The collection in the Art Institute Finding Aid/ includes over four hundred issues, with many complete runs of journals Search Collection represented. From architectural journals to radical literary reviews, this Related Websites selection of periodicals constitutes a revealing document of European Art Institute of artistic and literary life in the years spanning the two world wars. Chicago Home In the early part of the twentieth century, literary and artistic reviews were the primary means by which the creative community exchanged ideas and remained in communication. The journal was a vehicle for promoting emerging styles, establishing new theories, and creating a context for understanding new visual forms. These reviews played a pivotal role in forming the spirit and identity of movements such as Dada and Surrealism and served to spread their messages throughout Europe and the United States. -

Marcel Janco in Zurich and Bucharest, 1916-1939 a Thesis Submi

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Between Dada and Architecture: Marcel Janco in Zurich and Bucharest, 1916-1939 A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Adele Robin Avivi June 2012 Thesis Committee: Dr. Susan Laxton, Chairperson Dr. Patricia Morton Dr. Éva Forgács Copyright by Adele Robin Avivi 2012 The Thesis of Adele Robin Avivi is approved: ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Special thanks must first go to my thesis advisor Dr. Susan Laxton for inspiring and guiding my first exploration into Dada. This thesis would not have been possible without her enthusiastic support, thoughtful advice, and careful reading of its many drafts. Thanks are also due to Dr. Patricia Morton for her insightful comments that helped shape the sections on architecture, Dr. Éva Forgács for generously sharing her knowledge with me, and Dr. Françoise Forster-Hahn for her invaluable advice over the past two years. I appreciate the ongoing support and helpful comments I received from my peers, especially everyone in the thesis workshop. And thank you to Danielle Peltakian, Erin Machado, Harmony Wolfe, and Sarah Williams for the memorable laughs outside of class. I am so grateful to my mom for always nourishing my interests and providing me with everything I need to pursue them, and to my sisters Yael and Liat who cheer me on. Finally, Todd Green deserves very special thanks for his daily doses of encouragement and support. His dedication to his own craft was my inspiration to keep working. -

Dadaist Manifesto by Tristan Tzara, Franz Jung, George Grosz, Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Gerhard Preisz, Raoul Hausmann April 1918

dadaist manifesto by tristan tzara, franz jung, george grosz, marcel janco, richard huelsenbeck, gerhard preisz, raoul hausmann april 1918 Dadaist Manifesto (Berlin) The signatories of this manifesto have, under the battle cry DADA!!!! gathered together to put forward a new art from which they expect the realisation of new ideas. So what is DADAISM, then? The word DADA symbolises the most primitive relationship with the surrounding reality; with Dadaism, a new reality comes into its own. Life is seen in a simultaneous confusion of noises, colours and spiritual rhythms which in Dadaist art are immediately captured by the sensational shouts and fevers of its bold everyday psyche and in all its brutal reality. This is the dividing line between Dadaism and all other artistic trends and especially Futurism which fools have very recently interpreted as a new version of Impressionism. For the first time, Dadaism has refused to take an aesthetic attitude towards life. It tears to pieces all those grand words like ethics, culture, interiorisation which are only covers for weak muscles. THE BRUITIST POEM describes a tramcar exactly as it is, the essence of a tramcar with the yawns of Mr Smith and the shriek of brakes. THE SIMULTANEOUS POEM teaches the interrelationship of things, while Mr Smith reads his paper, the Balkan express crosses the Nisch bridge and a pig squeals in the cellar of Mr Bones the butcher. THE STATIC POEM turns words into individuals. The letters of the word " wood " create the forest itself with the leafiness of its trees, the uniforms of the foresters and the wild boar. -

Dada-Guide-Booklet HWB V5.Pdf

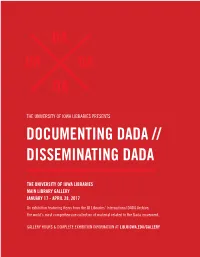

DA DA DA DA THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA LIBRARIES PRESENTS DOCUMENTING DADA // DISSEMINATING DADA THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA LIBRARIES MAIN LIBRARY GALLERY JANUARY 17 - APRIL 28, 2017 An exhibition featuring items from the UI Libraries' International DADA Archive, the world’s most comprehensive collection of material related to the Dada movement. GALLERY HOURS & COMPLETE EXHIBITION INFORMATION AT LIB.UIOWA.EDU/GALLERY EXHIBITION GUIDE 1 DOCUMENTING DADA // DISSEMINATING DADA From 1916 to 1923, a new kind of artistic movement Originating as an anti-war protest in neutral swept Europe and America. Its very name, “DADA” Switzerland, Dada rapidly spread to many corners —two identical syllables without the obligatory of Europe and beyond. The Dada movement was “-ism”—distinguished it from the long line of avant- perhaps the single most decisive influence on the gardes that had determined the preceding century of development of twentieth-century art, and its art history. More than a mere art movement, Dada innovations are so pervasive as to be virtually taken claimed a broader role as an agent of cultural, social, for granted today. and political change. This exhibition highlights a single aspect of Dada: Its proponents came from all parts of Europe and the its print publications. Since the essence of Dada was United States at a time when their native countries best reflected in ephemeral performances and actions were battling one another in the deadliest war ever rather than in concrete artworks, it is perhaps ironic known. They did not restrict themselves to a single that the dadaists produced many books and journals mode of expression as painter, writer, actor, dancer, of astonishing beauty. -

Dada Judaism: the Avant-Garde in First World War Zurich

Alfred Bodenheimer Dada Judaism: The Avant-Garde in First World War Zurich Wir armen Juden clagend hungersnot vnd müßend gar verzagen, hand kein brot. oime las compassio cullis mullis lassio Egypten was guot land, wau wau wau wiriwau, Egypten was guot land. This is not a dada text, yet it is similar to dada texts in several ways: like many dada poems, it consists of a mix of semantically recognizable words (in German), especially in the first two verses, as well as in the fifth and the last; it also has a syntactic order and suggests a meaning in the sense of practical, conventional language. Likewise, there are lines with unrecognizable words, either with a tonal- ity recalling Latin, or evoking the barking of a dog, additionally parodying the threefold “wau” (German for “woof”) with the line ending “wiriwau.” The main diference from dada texts is that the latter never spoke so explicitly about Jews (“Wir armen Juden”). The quoted text was printed in 1583, in a revised version of the Lucerne Passionsspiel. I have quoted it from the German translation of Sander L. Gilman’s Jewish Self-Hatred. Anti-Semitism and the Hidden Language of the Jews.¹ Gilman presents this quotation, spoken by the figures representing the Jews in the Passionsspiel, in order to demonstrate “the subhuman nature of the Jews’ lan- guage, a language of marginality” (1986, 76). Gilman also stresses that here, unlike in many other cases, the comic efect of Jewish speech prevails over fear of Jews and is more about making the audiences laugh rather than making them angry. -

Preannouncement Arp: the Poetry of Forms at the Kröller-Müller Museum

Preannouncement Otterlo, 25 October 2016 Arp: The Poetry of Forms at the Kröller-Müller Museum Arp: The Poetry of Forms is the first major retrospective of the work of Hans (Jean) Arp (Strasburg 1886-Basel 1966) in the Netherlands since the nineteen sixties. The German-French sculptor, painter and poet Arp is one of the most influential artists of the European avant-garde and plays an important role in the development of modern art. In addition to some eighty of his visual works – drawings, collages, paintings, wood reliefs and sculptures – there are also examples of Arp’s poetry, writings and publications. In 2017 it will be a hundred years since the founding of De Stijl. The close relationship between Arp and the leading light of De Stijl, Theo van Doesburg, is the occasion for the exhibition, which is showing from 20 May to 17 September 2017. Word and image In Arp: The Poetry of Forms, emphasis is placed on the constant interaction between visual art and poetry in Arp’s oeuvre and on the humour and playfulness in his works. Raised in the bilingual Alsace, the ease with which he switches from one language and culture to another and from visual art to poetry and back again, is characteristic for Arp’s entire career. The exhibition shows the powerful bond between word and image in his work. Jean Arp, Berger de nuages, 1953 Art and nature After the nadir of the First World War, Arp develops a visual idiom with which he aims to create a new order and be able to redesign the relationship between human, object and nature. -

A Companion to Dada and Surrealism

Edinburgh Research Explorer Feminist interventions Citation for published version: Allmer, P 2016, Feminist interventions: Revising the canon. in D Hopkins (ed.), A Companion to Dada and Surrealism. Wiley-Blackwell. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: A Companion to Dada and Surrealism General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 22 Feminist Interventions: Revising the Canon Patricia Allmer Women have always been significant, even foundational, figures in the histories of Dada and Surrealism. Many women artists developed and used dada and surrealist techniques, or contributed in multiple ways to the productions of the movements. These women’s works helped create some of the conditions of representation necessary for subsequent women’s rights activism, along with contemporary feminisms and women’s wider political interventions into structures of oppression. Evidence of this political activism can be found, for example, in the lives of Hannah Höch, Adrienne Monnier, Baroness Elsa von Freytag‐Lohringhoven, Madame Yevonde, Lee Miller, Frida Kahlo, Claude Cahun, Toyen, Suzanne Césaire, Lucie Thésée, and Birgit Jürgenssen.