A Companion to Dada and Surrealism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gordon Onslow Ford Voyager and Visionary

Gordon Onslow Ford Voyager and Visionary 11 February – 13 May 2012 The Mint Museum 1 COVER Gordon Onslow Ford, Le Vallee, Switzerland, circa 1938 Photograph by Elisabeth Onslow Ford, courtesy of Lucid Art Foundation FIGURE 1 Sketch for Escape, October 1939 gouache on paper Photograph courtesy of Lucid Art Foundation Gordon Onslow Ford: Voyager and Visionary As a young midshipman in the British Royal Navy, Gordon Onslow Ford (1912-2003) welcomed standing the night watch on deck, where he was charged with determining the ship’s location by using a sextant to take readings from the stars. Although he left the navy, the experience of those nights at sea may well have been the starting point for the voyages he was to make in his painting over a lifetime, at first into a fabricated symbolic realm, and even- tually into the expanding spaces he created on his canvases. The trajectory of Gordon Onslow Ford’s voyages began at his birth- place in Wendover, England and led to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth and to three years at sea as a junior officer in the Mediterranean and Atlantic fleets of the British Navy. He resigned from the navy in order to study art in Paris, where he became the youngest member of the pre-war Surrealist group. At the start of World War II, he returned to England for active duty. While in London awaiting a naval assignment, he organized a Surrealist exhibition and oversaw the publication of Surrealist poetry and artworks that had been produced the previous summer in France (fig. -

Univerzitet Umetnosti U Begoradu Ţensko Telo U

Univerzitet umetnosti u Begoradu Interdisciplinarne studije Teorija umetnosti i medija Doktorska disertacija Ţensko telo u nadrealističkoj fotografiji i filmu Autor: Lidija Cvetić F6/10 Mentor: dr.Milanka Todić, redovni profesor Beograd, decembar 2015. 1 Sadržaj: Apstrakt / Abstract/ 7 1. Uvod : O nadrealističke poetike ka teoriji tela/ 6 2. Žensko telo i poetika nadrealizma/ 16 2.1.Estetika znatiželje/ 16 2.1.1. Ikonografija znatiţelje/ 20 2.1.2. Topografija ţenske zavodljivosti/ 22 2.1.3. Znatiţeljni pogled/ 26 2.1.4. Dekonstrukcija pogleda/ 32 2.2.Mit i metamorfoze/ 38 2.2.1. Prostori magijskog u prostoru modernosti/ 38 2.2.2. Breton – Meluzine/ 41 2.2.3. Bataj – Lavirint/ 56 2.2.4. Nadrealisički koncept Informé/ 60 3. Fetišizacija i dekonstrukcija ženskog tela u praksama narealizma/ 69 3.1. Fetišizacija tela/ 69 3.1.1. Poreklo fetiša/ 70 3.1.2. Zamagljeni identitet/ 74 3.1.3. Ţensko telo – zabranjeno telo/ 78 3.2.Dekonstrukcija tela/ 82 3,2,1, Destrukcija – dekonstrukcija/ 82 3.2.2. Konvulzivni identitet/ 87 3.2.3. Histerično telo/ 89 4. Reprezentacijske prakse u vizuelnoj umetnosti nadrealizma/ 97 4.1.Telo kao objekt/ 97 4.1.1. Početak telesnih subverzija/ 101 4.1.2. Ţenski akt – izlaganje i fragmentacija/ 106 2 4.2.Telo kao dijalektički prostor označavanja/ 114 4.2.1. Ţensko telo kao sistem označavanja/ 114 4.2.2. Disbalans u reprezentaciji „polnosti”/ 117 4.2.3. Feministički jezik filma/ 125 4.1.4. Dijalektika tela/ 128 5. Performativnost i subverzije tela/ 134 5.1.Otpor identiteta-performativnost tela/ 134 5.1.1. -

Avantgarden Und Politik

Im Rausch der Revolution: Kunst und Politik bei André Masson und den surrealistischen Gruppierungen Contre-Attaque und Acéphale STEPHAN MOEBIUS Wirft man einen Blick auf die Debatten um die historische Avantgarde- bewegung des Surrealismus, so fällt auf, dass deren politisches Engage- ment1 in der Avantgardeforschung, in Ausstellungen und in der Kunst- geschichte allgemein auf spezifische und mehrere Weisen »gezähmt«2 wird: Entweder werden die politischen Aktivitäten der Surrealisten auf eine antibürgerliche Haltung reduziert oder sie werden als eine kurzzei- tige, von der »wahren« ästhetischen Praxis und den Kunstwerken der Surrealisten völlig abtrennbare Verirrung3 dargestellt. In manchen Inter- pretationen wirft man ihnen sogar vor, mit totalitären Systemen ver- wandt zu sein oder diese vorbereitet zu haben (Dröge/Müller 1995; Klinger 2004: 218). Im letzteren Fall gilt der (meist vor dem Hinter- grund der Totalitarismustheorie argumentierende) pauschale Vorwurf 1 Siehe dazu beispielsweise die Tractes surréalistes et déclarations collecti- ves 1922-1939 (Pierre 1980), Nadeau (1986), Short (1969) sowie Lewis (1988) und Spiteri/LaCoss (2003). 2 Vgl. Breuer (1997). Auch die Düsseldorfer Ausstellung (Spies 2002) über den Surrealismus machte eine Trennung zwischen Bildern und Manifes- ten, sie zähmte den Surrealismus und setzte die Bilder kaum in Beziehung zu den politischen Manifesten, Zeitschriften und Texten (vgl. Bürger 2002). 3 Vgl. Vailland (1948), Greenberg (1986), Alfred Barr (1936), William Ru- bin (1968). 89 STEPHAN MOEBIUS einer Geistesverwandtschaft mit dem Faschismus oder dem Stalinismus den gesamten historischen Avantgardebewegungen, ohne dass in den meisten Fällen im Einzelnen zwischen den unterschiedlichen Protago- nisten bzw. zwischen Surrealismus, Dadaismus, Bauhaus und dem fa- schistischen Futurismus unterschieden wird. Die Futuristen sind in der Tat kriegslüsterne Patrioten und spätere Parteigänger des italienischen Faschismus. -

Fotografías De Ruth Lechuga

¿QUÉ HACER EN OTROS MUSEOS? El Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes será el anfitrión de la exposición Olga Costa. OLGA COSTA. APUNTES DE Apuntes de la Naturaleza 1913-2013 hasta el 27 de octubre de este año. Olga Kostakowsky Fabricant, mejor conocida como Olga Costa, nacida en Leipzing, Alemania en 1913, llegó a México y se estableció en la Ciudad de México a los 12 LA NATURALEZA 1913-2013 años. Aquí conoció a Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo y Frida Kahlo. Inspirada por los grandes maestros, estudió en la Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas. En 1935, fecha de su matrimonio con José Chávez Morado, se mudó al estado de Guanajuato, donde regresó al mundo de la pintura para presentar su primera exposición en 1944 en la Galería de Arte Mexicano. Durante su vida artística formó • parte de la galería Espiral y recibió el Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes en 1990. » SUSANA RIVAS El Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes reúne 75 piezas de la artista con motivo del centenario de su nacimiento, bajo la curaduría de Juan Rafael Coronel. Durante el recorrido en salas, se pueden apreciar los temas recurrentes en las pinturas de Olga Costa, como retratos, autorretratos, paisajes, además la influencia que tuvieron sobre sus obras corrientes como la escuela al aire libre, el cubismo y el fauvismo, entre otras. Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes Av. Juárez y Eje Central s/n, Centro Histórico Martes a domingo, 10 a 17:30 h. 43 pesos Olga Costa, Hombre desnudo, Domingo entrada libre 1937, Colección particular 5512-2593 REMEDIOS VARO. -

Women Surrealists: Sexuality, Fetish, Femininity and Female Surrealism

WOMEN SURREALISTS: SEXUALITY, FETISH, FEMININITY AND FEMALE SURREALISM BY SABINA DANIELA STENT A Thesis Submitted to THE UNIVERSITY OF BIRMINGHAM for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music The University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The objective of this thesis is to challenge the patriarchal traditions of Surrealism by examining the topic from the perspective of its women practitioners. Unlike past research, which often focuses on the biographical details of women artists, this thesis provides a case study of a select group of women Surrealists – chosen for the variety of their artistic practice and creativity – based on the close textual analysis of selected works. Specifically, this study will deal with names that are familiar (Lee Miller, Meret Oppenheim, Frida Kahlo), marginal (Elsa Schiaparelli) or simply ignored or dismissed within existing critical analyses (Alice Rahon). The focus of individual chapters will range from photography and sculpture to fashion, alchemy and folklore. By exploring subjects neglected in much orthodox male Surrealist practice, it will become evident that the women artists discussed here created their own form of Surrealism, one that was respectful and loyal to the movement’s founding principles even while it playfully and provocatively transformed them. -

André Breton Och Surrealismens Grundprinciper (1977)

Franklin Rosemont André Breton och surrealismens grundprinciper (1977) Översättning Bruno Jacobs (1985) Innehåll Översättarens förord................................................................................................................... 1 Inledande anmärkning................................................................................................................ 2 1.................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.................................................................................................................................................. 8 3................................................................................................................................................ 12 4................................................................................................................................................ 15 5................................................................................................................................................ 21 6................................................................................................................................................ 26 7................................................................................................................................................ 30 8............................................................................................................................................... -

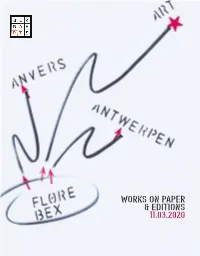

Works on Paper & Editions 11.03.2020

WORKS ON PAPER & EDITIONS 11.03.2020 Loten met '*' zijn afgebeeld. Afmetingen: in mm, excl. kader. Schattingen niet vermeld indien lager dan € 100. 1. Datum van de veiling De openbare verkoping van de hierna geïnventariseerde goederen en kunstvoorwerpen zal plaatshebben op woensdag 11 maart om 10u en 14u in het Veilinghuis Bernaerts, Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen 2. Data van bezichtiging De liefhebbers kunnen de goederen en kunstvoorwerpen bezichtigen Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen op donderdag 5 maart vrijdag 6 maart zaterdag 7 maart en zondag 8 maart van 10 tot 18u Opgelet! Door een concert op zondagochtend 8 maart zal zaal Platform (1e verd.) niet toegankelijk zijn van 10-12u. 3. Data van afhaling Onmiddellijk na de veiling of op donderdag 12 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u op vrijdag 13 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u en ten laatste op zaterdag 14 maart van 10 tot 12u via Verlatstraat 18 4. Kosten 23 % 28 % via WebCast (registratie tot ten laatste dinsdag 10 maart, 18u) 30 % via After Sale €2/ lot administratieve kost 5. Telefonische biedingen Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 Veilinghuis Bernaerts/ Bernaerts Auctioneers Verlatstraat 18 2000 Antwerpen/ Antwerp T +32 (0)3 248 19 21 F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 www.bernaerts.be [email protected] Biedingen/ Biddings F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 No telephone biddings when estimation is less than € 500 Live Webcast Registratie tot dinsdag 10 maart, 18u Identification till Tuesday 10 March, 6 pm Through Invaluable or Auction Mobility -

E 13 George Grosz (1893-1959) 'My New Pictures'

272 Rationalization and Transformation this date (1920) have sat in a somewhat strained relationship with the more overtly left-vi elements of the post-war German avant-garde. Originally published in Edschmid, op. cit. ~~g present translation is taken from Miesel, op. cit., pp. 180-1. e Work! Ecstasy! Smash your brains! Chew, stuff your self, gulp it down, mix it around! Th bliss of giving birth! The crack of the brush, best of all as it stabs the canvas. Tubes ~ 0 color squeezed dry. And the body? It doesn't matter. Health? Make yourself healthy! Sickness doesn't exist! Only work and I'll say that again - only blessed work! Paint' Dive into colors, roll around in tones! in the slush of chaos! Chew the broken-off mouthpiece of your pipe, press your naked feet into the earth. Crayon and pen pierce sharply into the brain, they stab into every corner, furiously they press into the whiteness. Black laughs like the devil on paper, grins in bizarre lines, comforts in velvety planes, excites and caresses. The storm roars - sand blows about - the sun shatters to pieces - and nevertheless, the gentle curve of the horizon quietly embraces everything. Beaten down, exhausted, just a worm, collapse into your bed. A deep sleep will make you forget your defeat. A new day! A new struggle! Ecstasy again! One day after the other, a sparkling, constantly changing chain of days. One experience after the other. That damned brain! What is it that churns and twitches and jumps in there? Hah! Tear your head off, or grab it with both hands, turn it around, twist it off. -

Genius Is Nothing but an Extravagant Manifestation of the Body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914

1 ........................................... The Baroness and Neurasthenic Art History Genius is nothing but an extravagant manifestation of the body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914 Some people think the women are the cause of [artistic] modernism, whatever that is. — New York Evening Sun, 1917 I hear “New York” has gone mad about “Dada,” and that the most exotic and worthless review is being concocted by Man Ray and Duchamp. What next! This is worse than The Baroness. By the way I like the way the discovery has suddenly been made that she has all along been, unconsciously, a Dadaist. I cannot figure out just what Dadaism is beyond an insane jumble of the four winds, the six senses, and plum pudding. But if the Baroness is to be a keystone for it,—then I think I can possibly know when it is coming and avoid it. — Hart Crane, c. 1920 Paris has had Dada for five years, and we have had Else von Freytag-Loringhoven for quite two years. But great minds think alike and great natural truths force themselves into cognition at vastly separated spots. In Else von Freytag-Loringhoven Paris is mystically united [with] New York. — John Rodker, 1920 My mind is one rebellion. Permit me, oh permit me to rebel! — Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, c. 19251 In a 1921 letter from Man Ray, New York artist, to Tristan Tzara, the Romanian poet who had spearheaded the spread of Dada to Paris, the “shit” of Dada being sent across the sea (“merdelamerdelamerdela . .”) is illustrated by the naked body of German expatriate the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (see fig. -

2 0 0 Jt COPYRIGHT This Is a Thesis Accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year Name of Author 2 0 0 jT COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Catalogue of Sans Pareil Publications on the Verso

Rare Books Le Feu Follet Edition-Originale.com 31 rue Henri Barbusse 75005 Paris [email protected] France +33 1 56 08 08 85 +33 6 09 25 60 47 Bank Rothschild Martin Maurel IBAN FR7613369000 126406710101240 SWIFT BMMMFR2A Visa, Mastercard, Paypal, American Express VAT no. FR45 412 079 873 americana 1 National Liberal Immigration League Unique and significant collection of 170 documents: set of pamphlets, correspondence and off-print articles 1906-1914 | 25 X 29 CM | FULL MOROCCO Unique and significant collection of 170 documents from the National Lib- eral Immigration League. The collection is divided into three parts: the first is dedicated to the pamphlets published by the League, the second recounts its correspondence and the final part is a collection of off-print articles linked to immigration published in American dai- ly newspapers. All of these documents, in perfect condition, are mounted on guards, bound or set in made to mea- sure frames. Except for some isolated pamphlets, we have not been able to find such a complete collection in any American or European library. Contemporary binding in navy blue mo- rocco, spine in five compartments richly decorated with fillets and large gilt mo- tifs, plates framed with triple gilt fillets migratory flow gave rise to the introduc- convinced that his mission in America with a large typographical gilt motif tion of restrictive legislation. It is with- was not only to help Jewish immigrants stamped in the centre. In the middle of in this context that the National Liberal from Eastern Europe to adapt to their first board, the initials of the National Immigration League gets going in 1906. -

A Promenade Trough the Visual Arts in Carlos Monsivais Collection

A Promenade Trough the Visual Arts in Carlos Monsivais Collection So many books have been written, all over the world and throughout all ages about collecting, and every time one has access to a collection, all the alarms go off and emotions rise up, a new and different emotion this time. And if one is granted access to it, the pleasure has no comparison: with every work one starts to understand the collector’s interests, their train of thought, their affections and their tastes. When that collector is Carlos Monsiváis, who collected a little bit of everything (that is not right, actually it was a lot of everything), and thanks to work done over the years by the Museo del Estanquillo, we are now very aware of what he was interested in terms of visual art in the 20th Century (specially in painting, illustration, engraving, photography). It is only natural that some of the pieces here —not many— have been seen elsewhere, in other exhibitions, when they were part of the main theme; this time, however, it is a different setting: we are just taking a stroll… cruising around to appreciate their artistic qualities, with no specific theme. This days it is unusual, given that we are so used to looking for an overarching “theme” in every exhibition. It is not the case here. Here we are invited to partake, along with Carlos, in the pleasures of color, texture, styles and artistic schools. We’ll find landscapes, portraits, dance scenes, streetscapes, playful scenes. All executed in the most diverse techniques and styles by the foremost mexican artist of the 20th Century, and some of the 21st as well.