Gordon Onslow Ford Voyager and Visionary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sonja Sekula's Time May Have Finally Come

PETER BLUM GALLERY Sonja Sekula’s Time May Have Finally Come Sekula was part of a number of different overlapping scenes, and she was loved and thought highly of by many. And then nearly everything about her and her work got forgotten. GALLERIES | WEEKEND By John Yau Saturday April 29, 2017 Sonja Sekula (1918-1963) piqued my curiosity when I first saw some of her works just a few months ago. Still, I was not sure what to expect when I went to the current exhibition Sonja Sekula: A Survey at Peter Blum Gallery (April 21 – June 24, 2017). I had known that this troubled, Swiss-born artist was part of an international circle of artists, writers, choreographers, and composers in New York in the 1940s, when she was in her early twenties, and that since her death by suicide in 1963, she and her work have largely been effaced from history. But aside from a few biographical facts and the handful of works I saw, I knew little else, but it was more than enough to bring me back. Ethnique, (1961), gouache on paper, 20 1/8 x 20 1/8 inches (all images courtesy Peter Blum At one point, while circling the Gallery, New York) galleries two space for the second or third time, I stopped to peer into a vitrine and saw photographs of a young woman sitting in the apartment of Andre Breton when he lived in New York during World War II. In another photograph she and sister are hugging Frida Kahlo, who is recuperating in a New York hospital room. -

Libro Completo

DESDE ESPAÑA Y SERBIA HACIA IBEROAMÉRICA EL AUGE DE LA LITERATURA, LA FILOLOGÍA Y LA HISTORIA MATTEO RE, BOJANA KOVAČEVIĆ PETROVIĆ, JOSÉ MANUEL AZCONA [EDS.] Desde España y Serbia hacia Iberoamérica © Matteo Re, Bojana Kovačević Petrović, José Manuel Azcona [Eds.], Madrid, 2020. ISBN: 978-84-09-21626-0 Ninguna página de este libro puede ser fotocopiada y reproducida sin autorización de los editores. Este libro es el resultado del proyecto de investigación amparado en el Artículo 83, de la LOU (Ley Orgánica de Universidades 6/2001 de 21 de diciembre) de la Cátedra de Excelencia URJC Santander Presdeia con la referencia siguiente : F47-HC/Cat-Ib-2019-2020: Desde España y Serbia hacia Iberoamérica. El auge de la literatura, la filología y la historia (Vicerrectorado de Innovación y Transferencia). 2 Desde España y Serbia hacia Iberoamérica ÍNDICE PRÓLOGO ........................................................................................................................................ 5 LA FRONTERA METAFÍSICA EN EL CONO SUR AMERICANO (1810-1880) ....................... 11 José Manuel Azcona y Majlinda Abdiu HISTORIA Y HERENCIA CULTURAL DE ALGUNOS PUEBLOS EUROPEOS EN ARGENTINA .................................................................................................................................. 40 Anja Mitić SERBIA, ESPAÑA E IBEROAMÉRICA: ENTRECRUZAMIENTOS HISTÓRICOS Y CULTURALES ................................................................................................................................ 62 Bojana Kovačević -

Homage to Roberto Matta

FIAC PARIS | BOOTH C29 | GRAND PALAIS | OCTOBER 17–20, 2019 At this year’s FIAC, in honor of the late Germana Matta, we will mount an Homage to Roberto Matta Paris was one of the principal residencies of Matta. The exhibition will therefore include parts of the archives and sketchbooks from Matta’s Parisian home. The core of the presentation consists of three highly important large scale works, executed between 1947 and 1958. It will be complemented by midsize works on canvas and paper as well as sculptures. Matta’s influence can be felt both in today’s Contemporary Art as well as in the Tech-World; his impact on fellow New York artists in the 1940’s was summarized by nobody other than Marcel Duchamp: “Still a young man, Matta is the most profound painter of his generation” MARCEL DUCHAMP, 1944 While the legendary MoMA curator and Picasso Scholar William Rubin had this to say about Matta: “Matta became the only painter after Duchamp to explore wholly new possibilities in illusionistic space” WILLIAM RUBIN, 1985 For more information on our FIAC exhibition and Matta please contact Mathias Rastorfer: [email protected] Additional works to be shown are by Yves Klein, Wifredo Lam, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso, Antonio Saura ABOUT GALERIE GMURZYNSKA Founded in Cologne in 1965, Galerie Gmurzynska has been a leading international art gallery specializing in masterpieces of both classic modern and post-war art for more than 50 years. Galerie Gmurzynska is also the prime gallery worldwide for artists of the Russian avant-garde and early 20th century abstraction. -

André Breton Och Surrealismens Grundprinciper (1977)

Franklin Rosemont André Breton och surrealismens grundprinciper (1977) Översättning Bruno Jacobs (1985) Innehåll Översättarens förord................................................................................................................... 1 Inledande anmärkning................................................................................................................ 2 1.................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.................................................................................................................................................. 8 3................................................................................................................................................ 12 4................................................................................................................................................ 15 5................................................................................................................................................ 21 6................................................................................................................................................ 26 7................................................................................................................................................ 30 8............................................................................................................................................... -

Drawing Surrealism Didactics 10.22.12.Pdf

^ Drawing Surrealism Didactics Drawing Surrealism is the first-ever large-scale exhibition to explore the significance of drawing and works on paper to surrealist innovation. Although launched initially as a literary movement with the publication of André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, surrealism quickly became a cultural phenomenon in which the visual arts were central to envisioning the world of dreams and the unconscious. Automatic drawings, exquisite corpses, frottage, decalcomania, and collage are just a few of the drawing-based processes invented or reinvented by surrealists as means to tap into the subconscious realm. With surrealism, drawing, long recognized as the medium of exploration and innovation for its use in studies and preparatory sketches, was set free from its associations with other media (painting notably) and valued for its intrinsic qualities of immediacy and spontaneity. This exhibition reveals how drawing, often considered a minor medium, became a predominant mode of expression and innovation that has had long-standing repercussions in the history of art. The inclusion of drawing-based projects by contemporary artists Alexandra Grant, Mark Licari, and Stas Orlovski, conceived specifically for Drawing Surrealism , aspires to elucidate the diverse and enduring vestiges of surrealist drawing. Drawing Surrealism is also the first exhibition to examine the impact of surrealist drawing on a global scale . In addition to works from well-known surrealist artists based in France (André Masson, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, among them), drawings by lesser-known artists from Western Europe, as well as from countries in Eastern Europe and the Americas, Great Britain, and Japan, are included. -

Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 Ó Copyright by Joanna Marie Fiduccia 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Hollow Man: Alberto Giacometti and the Crisis of the Monument, 1935–45 by Joanna Marie Fiduccia Doctor of Philosophy in Art History University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor George Thomas Baker, Chair This dissertation presents the first extended analysis of Alberto Giacometti’s sculpture between 1935 and 1945. In 1935, Giacometti renounced his abstract Surrealist objects and began producing portrait busts and miniature figures, many no larger than an almond. Although they are conventionally dismissed as symptoms of a personal crisis, these works unfold a series of significant interventions into the conventions of figurative sculpture whose consequences persisted in Giacometti’s iconic postwar work. Those interventions — disrupting the harmonious relationship of surface to interior, the stable scale relations between the work and its viewer, and the unity and integrity of the sculptural body — developed from Giacometti’s Surrealist experiments in which the production of a form paradoxically entailed its aggressive unmaking. By thus bridging Giacometti’s pre- and postwar oeuvres, this decade-long interval merges two ii distinct accounts of twentieth-century sculpture, each of which claims its own version of Giacometti: a Surrealist artist probing sculpture’s ambivalent relationship to the everyday object, and an Existentialist sculptor invested in phenomenological experience. This project theorizes Giacometti’s artistic crisis as the collision of these two models, concentrated in his modest portrait busts and tiny figures. -

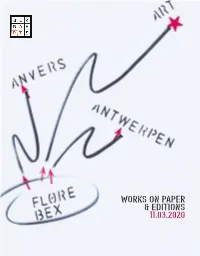

Works on Paper & Editions 11.03.2020

WORKS ON PAPER & EDITIONS 11.03.2020 Loten met '*' zijn afgebeeld. Afmetingen: in mm, excl. kader. Schattingen niet vermeld indien lager dan € 100. 1. Datum van de veiling De openbare verkoping van de hierna geïnventariseerde goederen en kunstvoorwerpen zal plaatshebben op woensdag 11 maart om 10u en 14u in het Veilinghuis Bernaerts, Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen 2. Data van bezichtiging De liefhebbers kunnen de goederen en kunstvoorwerpen bezichtigen Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen op donderdag 5 maart vrijdag 6 maart zaterdag 7 maart en zondag 8 maart van 10 tot 18u Opgelet! Door een concert op zondagochtend 8 maart zal zaal Platform (1e verd.) niet toegankelijk zijn van 10-12u. 3. Data van afhaling Onmiddellijk na de veiling of op donderdag 12 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u op vrijdag 13 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u en ten laatste op zaterdag 14 maart van 10 tot 12u via Verlatstraat 18 4. Kosten 23 % 28 % via WebCast (registratie tot ten laatste dinsdag 10 maart, 18u) 30 % via After Sale €2/ lot administratieve kost 5. Telefonische biedingen Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 Veilinghuis Bernaerts/ Bernaerts Auctioneers Verlatstraat 18 2000 Antwerpen/ Antwerp T +32 (0)3 248 19 21 F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 www.bernaerts.be [email protected] Biedingen/ Biddings F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 No telephone biddings when estimation is less than € 500 Live Webcast Registratie tot dinsdag 10 maart, 18u Identification till Tuesday 10 March, 6 pm Through Invaluable or Auction Mobility -

Es Probable, De Hecho, Que La Invencible Tristeza En La Que Se

Surrealismo y saberes mágicos en la obra de Remedios Varo María José González Madrid Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement- NoComercial – CompartirIgual 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento - NoComercial – CompartirIgual 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0. Spain License. 2 María José González Madrid SURREALISMO Y SABERES MÁGICOS EN LA OBRA DE REMEDIOS VARO Tesis doctoral Universitat de Barcelona Departament d’Història de l’Art Programa de doctorado Història de l’Art (Història i Teoria de les Arts) Septiembre 2013 Codirección: Dr. Martí Peran Rafart y Dra. Rosa Rius Gatell Tutoría: Dr. José Enrique Monterde Lozoya 3 4 A María, mi madre A Teodoro, mi padre 5 6 Solo se goza consciente y puramente de aquello que se ha obtenido por los caminos transversales de la magia. Giorgio Agamben, «Magia y felicidad» Solo la contemplación, mirar una imagen y participar de su hechizo, de lo revelado por su magia invisible, me ha sido suficiente. María Zambrano, Algunos lugares de la pintura 7 8 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 13 A. LUGARES DEL SURREALISMO Y «LO MÁGICO» 27 PRELUDIO. Arte moderno, ocultismo, espiritismo 27 I. PARÍS. La «ocultación del surrealismo»: surrealismo, magia 37 y ocultismo El surrealismo y la fascinación por lo oculto: una relación polémica 37 Remedios Varo entre los surrealistas 50 «El giro ocultista sobre todo»: Prácticas surrealistas, magia, 59 videncia y ocultismo 1. «El mundo del sueño y el mundo real no hacen más que 60 uno» 2. -

Networking Surrealism in the USA. Agents, Artists and the Market

151 Toward a New “Human Consciousness”: The Exhibition “Adventures in Surrealist Painting During the Last Four Years” at the New School for Social Research in New York, March 1941 Caterina Caputo On January 6, 1941, the New School for Social Research Bulletin announced a series of forthcoming surrealist exhibitions and lectures (fig. 68): “Surrealist Painting: An Adventure into Human Consciousness; 4 sessions, alternate Wednesdays. Far more than other modern artists, the Surrea- lists have adventured in tapping the unconscious psychic world. The aim of these lectures is to follow their work as a psychological baro- meter registering the desire and impulses of the community. In a series of exhibitions contemporaneous with the lectures, recently imported original paintings are shown and discussed with a view to discovering underlying ideas and impulses. Drawings on the blackboard are also used, and covered slides of work unavailable for exhibition.”1 From January 22 to March 19, on the third floor of the New School for Social Research at 66 West Twelfth Street in New York City, six exhibitions were held presenting a total of thirty-six surrealist paintings, most of which had been recently brought over from Europe by the British surrealist painter Gordon Onslow Ford,2 who accompanied the shows with four lectures.3 The surrealist events, arranged by surrealists themselves with the help of the New School for Social Research, had 1 New School for Social Research Bulletin, no. 6 (1941), unpaginated. 2 For additional biographical details related to Gordon Onslow Ford, see Harvey L. Jones, ed., Gordon Onslow Ford: Retrospective Exhibition, exh. -

Derek Sayer ANDRÉ BRETON and the MAGIC CAPITAL: an AGONY in SIX FITS 1 After Decades in Which the Czechoslovak Surrealist Group

Derek Sayer ANDRÉ BRETON AND THE MAGIC CAPITAL: AN AGONY IN SIX FITS 1 After decades in which the Czechoslovak Surrealist Group all but vanished from the art-historical record on both sides of the erstwhile Iron Curtain, interwar Prague’s standing as the “second city of surrealism” is in serious danger of becoming a truth universally acknowledged.1 Vítězslav Nezval denied that “Zvěrokruh” (Zodiac), which appeared at the end of 1930, was a surrealist magazine, but its contents, which included his translation of André Breton’s “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” (1929), suggested otherwise.2 Two years later the painters Jindřich Štyrský and Toyen (Marie Čermínová), the sculptor Vincenc Makovský, and several other Czech artists showed their work alongside Hans/Jean Arp, Salvador Dalí, Giorgio De Chirico, Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Joan Miró, Wolfgang Paalen, and Yves Tanguy (not to men- tion a selection of anonymous “Negro sculptures”) in the “Poesie 1932” exhibition at the Mánes Gallery.3 Three times the size of “Newer Super-Realism” at the Wads- worth Atheneum the previous November – the first surrealist exhibition on Ameri- 1 Not one Czech artist was included, for example, in MoMA’s blockbuster 1968 exhibition “Dada, Surrealism, and Their Heritage” or discussed in William S. Rubin’s accompanying monograph “Dada and Surrealist Art” (New York 1968). – Recent western works that seek to correct this picture include Tippner, Anja: Die permanente Avantgarde? Surrealismus in Prag. Köln 2009; Spieler, Reinhard/Auer, Barbara (eds.): Gegen jede Vernunft: Surrealismus Paris-Prague. Ludwigshafen 2010; Anaut, Alberto (ed.): Praha, Paris, Barcelona: moderni- dad fotográfica de 1918 a 1948/Photographic Modernity from 1918 to 1948. -

Salvador Dalí. Óscar Domínguez Surrealism and Revolution

Salvador Dalí. Óscar Domínguez Surrealism and Revolution The publication in 1929 of the Second Manifesto of Surrealism marked a new stage in surrealism, character- ised by a move closer to revolutionary ideologies aimed at transforming not just art but society and its whole moral doctrine. Fundamental to this new stage was the innovative drive of two Spanish artists: Salvador Dalí and Óscar Domínguez. The founding of the journal Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution Dalí attempted to translate the mind’s dreamlike processes into in 1930 offers an exemplary account of the ideological premise that painting, exhibited in Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams. Aside the surrealist movement had achieved. The year before, the second from his admiration for Freud, Dalí’s encounter with Jacques surrealist manifesto proposed its “threefold revolution in solidarity”: Lacan in 1932, shortly after the artist published his thesis on that is, an artistic and literary transformation, a moral transformation paranoia, would greatly influence his work. Soon after, Dalí would and a societal transformation. In this manner, the connections some develop his “Paranoiac-Critical Method,” which entailed an en- artists had to the Communist Party and its influence on the surrealist tire revolution for the movement. This method, which drew from movement were made explicit. surrealist techniques, distinguished itself from the others in two In its second stage, the movement needed to reinvent itself, and two main aspects: by introducing the active condition and realism figures like Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) and Óscar Domínguez (1906- to the movement. On the one hand, Dalí’s method rejected the 1957) could foster this necessary change. -

Oral History Interview with Luchita Hurtado

Oral history interview with Luchita Hurtado The digital preservation of this interview received Federal support from the Latino Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Luchita Hurtado AAA.hurtad94 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Luchita Hurtado Identifier: AAA.hurtad94