The Journal of Scottish Name Studies Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Place-Names in This Book Were Collected As Part of The

Introduction The place-names in this book were collected as part of the Arts and Humanities Research Board-funded (AHRB) ‘Norse-Gaelic Frontier Project, which ran from autumn 2000 to summer 2001, the full details of which will be published as Crawford and Taylor (forthcoming). Its main aim was to explore the toponymy of the drainage basin of the River Beauly, especially Strathglass,1 with a view to establishing the nature and extent of Norse place-name survival along what had been a Norse-Gaelic frontier in the 11th century. While names of Norse origin formed the ultimate focus of the Project, much wider place-name collection and analysis had to be undertaken, since it is impossible to study one stratum of the toponymy of an area without studying the totality. The following list of approximately 500 names, mostly with full analysis and early forms, many of which were collected from unpublished documents, has been printed out from the Scottish Place-Name Database, for more details of which see Appendix below. It makes no claims to being comprehensive, but it is hoped that it will serve as the basis for a more complete place-name survey of an area which has hitherto received little serious attention from place-name scholars. Parishes The parishes covered are those of Kilmorack KLO, Kiltarlity & Convinth KCV, and Kirkhill KIH (approximately 240, 185 and 80 names respectively), all in the pre-1975 county of Inverness-shire. The boundaries of Kilmorack parish, in the medieval diocese of Ross, first referred to in the medieval record as Altyre, have changed relatively little over the centuries. -

Progress in Colour Studies 2012: List of Abstracts

Progress in Colour Studies 2012: List of abstracts Keynote lecture Prehistoric Colour Semantics: a Contradiction in Terms C. P. Biggam, University of Glasgow, UK The term prehistory indicates a time before written records, so how can we possibly understand the colour systems of prehistoric peoples? This paper will attempt to make a case, in relation to the distant past of the Indo-European family, that it is possible to provide a reasonable ‘reconstruction’ of certain concepts in languages for which there have been no living native speakers for many centuries. The argument will be presented that there are several disparate strands of evidence, all of them fragmentary, which can be brought together and viewed against the background of certain techniques and hypotheses employed by anthropologists, historical linguists, psychologists and archaeologists. The discussion will include indications, hints and evidence from the following: the colour systems of modern languages; colour category prototypes; the known techno-economic advances of prehistoric peoples; the identification of cognates in related languages; linguistic ‘primitives’; relative chronology; relative basicness; and the earliest Indo-European texts. It is hoped that the paper will provide a convincing argument that, because colour concepts can be approached from so many directions, this field provides one of the best chances we have to glimpse the workings of prehistoric minds. Blackguards, Whitewash, Yellow Belly and Blue Collars: Metaphors of English colours [oral presentation] Marc Alexander, Wendy Anderson, Ellen Bramwell, Flora Edmonds, Carole Hough and Christian Kay, University of Glasgow, UK The Historical Thesaurus of English, published in 2009 as the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary, contains the recorded vocabulary of the language from Old English to the present day. -

Irish Language in Meals Will Also Be Available on Reservation

ISSN 0257-7860 Nr. 57 SPRING 1987 80p Sterling D eatp o f S gum äs Mac a’ QpobpaiNN PGRRaNpORtb CONfGRGNCC Baase Doolisl) y KaRRaqpeR Welsb LaNquaqc Bills PlaNNiNQ CONtROl Q tpc MaNX QOVGRNMCNt HistORic OwiNNiNG TTpe NoRtp — Loyalist Attituöes A ScaSON iN tl7G FRGNCb CgRip Q0DC l£AGU€ -4LBA: COVIUNN CEIUWCH * BREIZH: KEl/RE KEU1EK Cy/VIRU: UNDEB CELMIDO *ElRE:CONR4DH CfllTHCH KERN O W KE SU NW NS KELTEK • /VWNNIN1COV1MEEY5 CELM GH ALBA striipag bha turadh ann. Dh'fhäs am boireannach na b'lheärr. Sgtiir a deöir. AN DIOGHALTAS AICE "Gun teagamh. fliuair sibh droch naidheachd an diugh. Pheigi." arsa Murchadh Thormaid, "mur eil sibh deönach mise doras na garaids a chäradh innsibh dhomh agus di- 'Seinn iribh o. hiüraibh o. hiigaibh o hi. chuimhnichidh mi c. Theid mi air eeann- Seo agaibh an obair bheir togail fo m'chridh. gnothaich (job) eite. Bhi stiuradh nio chasan do m'dhachaidh bhig fhin. "O cäraichidh sinn doras na garaids. Ma Air criochnacbadh saothair an lä dhomh." tha sibh deiseil tägaidh sinn an drasda agus seallaidh mi dhuibh doras na garaids. Tha Sin mar a sheinn Murchadh Thormaid chitheadh duine gun robh Murchadh 'na turadh ann." "nuair a thill e dhachaidh. "Nuair a bha c dhuine deannta 'na shcacaid dhubh-ghorm Agus leis a sin choisich an triuir a-mach a' stiiiireadh a’ chäir dhachaidh. bha eagail agus na dhungairidhe (dungarees), Bha baga dhan gharaids, an saor ’na shcacaid dhubh- air nach maircadh an ehr bochd air an rarhad uainc aige le chuid inncaian saoir. Bha e mu gorm is dungairidhc , . -

The Role and Importance of the Welsh Language in Wales's Cultural Independence Within the United Kingdom

The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain Scaglia To cite this version: Sylvain Scaglia. The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom. Linguistics. 2012. dumas-00719099 HAL Id: dumas-00719099 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00719099 Submitted on 19 Jul 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DU SUD TOULON-VAR FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES MASTER RECHERCHE : CIVILISATIONS CONTEMPORAINES ET COMPAREES ANNÉE 2011-2012, 1ère SESSION The role and importance of the Welsh language in Wales’s cultural independence within the United Kingdom Sylvain SCAGLIA Under the direction of Professor Gilles Leydier Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................. 1 WALES: NOT AN INDEPENDENT STATE, BUT AN INDEPENDENT NATION ........................................................ -

Report on the Current Position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020

Dumfries and Galloway Council Report on the current position of Poverty and Deprivation in Dumfries and Galloway 2020 3 December 2020 1 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. National Context 2 3. Analysis by the Geographies 5 3.1 Dumfries and Galloway – Geography and Population 5 3.2 Geographies Used for Analysis of Poverty and Deprivation Data 6 4. Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 10 4.1 Comparisons with the Crichton Institute Report and Trends over Time 13 5. Poverty at the Local Level 16 5.1 Digital Connectivity 17 5.2 Education and Skills 23 5.3 Employment 29 5.4 Fuel Poverty 44 5.5 Food Poverty 50 5.6 Health and Wellbeing 54 5.7 Housing 57 5.8 Income 67 5.9 Travel and Access to Services 75 5.10 Financial Inclusion 82 5.11 Child Poverty 85 6. Poverty and Protected Characteristics 88 6.1 Age 88 6.2 Disability 91 6.3 Gender Reassignment 93 6.4 Marriage and Civil Partnership 93 6.5 Pregnancy and Maternity 93 6.6 Race 93 6.7 Religion or Belief 101 6.8 Sex 101 6.9 Sexual Orientation 104 6.10 Veterans 105 7. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Poverty in Scotland 107 8. Summary and Conclusions 110 8.1 Overview of Poverty in Dumfries and Galloway 110 8.2 Digital Connectivity 110 8.3 Education and Skills 111 8.4 Employment 111 8.5 Fuel Poverty 112 8.6 Food Poverty 112 8.7 Health and Wellbeing 113 8.8 Housing 113 8.9 Income 113 8.10 Travel and Access to Services 114 8.11 Financial Inclusion 114 8.12 Child Poverty 114 8.13 Change Since 2016 115 8.14 Poverty and Protected Characteristics 116 Appendix 1 – Datazones 117 2 1. -

Thomas Carlyle and Juniper Green

www.junipergreen300.com Thomas Carlyle and Juniper Green Thomas Carlyle by Walter Greaves about 1879. Thomas Carlyle, 1795 - 1881. Historian and essayist A giant of nineteenth-century thought, Thomas Carlyle was the son of a stone- mason and was born in Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire. After graduating from Edinburgh University, he began to produce the articles, translations, essays and histories which were to make him world-famous. Carlyle and his gifted wife Jane lived in London, and their home in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, became a place of pilgrimage for intellectuals from all over Europe. Greaves was a neighbour and made the studies for this portrait while Carlyle was sitting for James McNeil Whistler. National Portrait Gallery of Scotland. There has long been a tradition in Juniper Green that Thomas Carlyle, that eminent Victorian, spent some time in the village not long after his marriage to Jane Welsh. Thomas Carlyle was born on the 4th December, 1795, at Ecclefechan, Dumfriesshire the second son of James Carlyle, and the eldest child of his second marriage. Thomas and Jane Carlyle married on October 17th, 1826 at Templand, Thornhill, in Dumfriesshire and moved to Comely Page 1 Bank, Edinburgh, their first home, on the same day. It follows that any sojourn by Carlyle in Juniper Green must have been in the late 1820s. The earliest mention of this tradition so far found is in ‘Old and New Edinburgh’ by James Grant Vol. III Chapter XXXVIII p. 323 where it states: “Near Woodhall in the parish of Colinton, is the little modern village of Juniper Green, chiefly celebrated as being the temporary residence of Thomas Carlyle some time after his marriage at Comely Bank, Stockbridge where, as he tells us in his “Reminiscences” (edited by Mr Froude), “his first experience in the difficult task of housekeeping began”. -

A Message from Our Interim Moderator

www.kiltarlityandkirkhill.org.uk Kiltarlity and Wardlaw Churches A MESSAGE FROM OUR INTERIM MODERATOR Dear Friends, There is a moving story about a man called Charnet who was a political prisoner in France in the days of Napoleon. He was thrown into prison simply because he had accidentally, by a remark, offended the emperor Napoleon. Cast into a dungeon cell, presumably left to die, as the days and weeks and months passed by, Charnet became embittered at his fate. Slowly but surely he began to lose his faith in God. And one day, in a moment of rebellious anger, he scratched on the wall of his cell, "All things come by chance," which reflected the injustice that had come his way by chance. He sat in the darkness of that cell growing more bitter by the day. There was one spot in the cell where a single ray of sunlight came every day and remained for a little while. And one morning, to his absolute amazement, he noticed that in the hard, earthen floor of that cell a tiny, green blade was breaking through. It was something living, struggling up toward that shaft of sunlight. It was his only living companion, and his heart went out in joy toward it. He nurtured it with his tiny ration of water, cultivated it, and encouraged its growth. That green blade became his friend. It became his teacher in a sense, and finally it burst through until one day there bloomed from the little plant a beautiful, purple and white flower. Once again Charnet found himself thinking thoughts about God. -

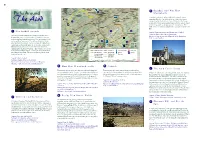

C:\MYDOCU~1\ACCESS~2\Aird\New Aird Inside.Pmd

Wester To Inverness Lovat Kirkhill 6 Kirkhill and Wardlaw Wardlaw 6 Paths Around Beauly Mausoleum Ferry Brae Bogroy A roadside path to the village of Kirkhill and to the burial To Lentran Beauly ground used by the Clan Fraser of Lovat. Robert the Bruce’s The Aird 7 Inchmore chamberlain was Sir Alexander Fraser. His brother, Sir Simon A862 acquired the Bisset Lands around Beauly when he won the hand ! of its heiress, and these lands became the family home. The walk can be extended by following the cycle route as far as Ferry Brae. 1 Newtonhill circuits 1 2 ! Cabrich Approx 5 kms round trip to the Mausoleum (3.1 miles) Moniack Newtonhill Castle Parking at Bogroy Inn or at the Mausoleum This varied circular walk on quiet country roads provides a A833 A Bus service from Inverness and Dingwall to the Bogroy Inn flavour of what the Aird has to offer; agricultural landscape, 5 To Easy - sensible footwear natural woodland, plantations of Scots Pine and mature beech To Kiltarlity Kirkton and magnificent panoramas. The route provides links to the 4 3 Muir other paths in the network. It offers views to the Fannich and Belladrum Mám Mòr To the Affric ranges to the north and west, views to the east down the 8 Reelig Great Moray Firth and some of the best views to Ben Wyvis. The THE AIRD A Glen Glen Way climb from Reelig Glen is worth the effort with the descent via Newtonhill and Drumchardine, a former weaving community A Phoineas Newtonhill Circuit The Cabrich Tourist Information A Access point providing an easy finish. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plans

Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plans 1 2 Contents Page 2 Chairman’s Introduction Page 3 Arthuret Community Plan Introduction Page 4 Kirkandrews-on-Esk Plan Introduction Page 5 Arthuret Parish background and History Page 7 Brief outline of Kirkandrews on Esk Parish and History Page 9 Arthuret Parish Process Page 12 Kirkandrews on Esk Parish Process Page 18 The Action Plan 3 Chairman’s Introduction Welcome to the Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan – a joint Community Action Plan for the parishes of Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk. The aim is to encourage local people to become involved in ensuring that what matters to them – their ideas and priorities – are identified and can be acted upon. The Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan is based upon finding out what you value in your community. Then, based upon the process of consultation, debate and dialogue, producing an Action Plan to achieve the aspirations of local people for the community you live and work in. The consultation process took several forms including open days, questionnaires, workshops, focus group meetings, even a business speed dating event. The process was interesting, lively and passionate, but extremely important and valuable in determining the vision that you have for your community. The information gathered was then collated and produced in the following Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan. The Action Plan aims to show a balanced view point by addressing the issues that you want to be resolved and celebrating the successes we have achieved. It contains a range of priorities from those which are aspirational to those that can be delivered with a few practical steps which will improve life in our community. -

Inverness Local Plan Public Local Inquiry Report- Volume 3

TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (SCOTLAND) ACT 1997 REPORT OF PUBLIC LOCAL INQUIRY INTO OBJECTIONS TO THE INVERNESS LOCAL PLAN VOLUME 3 THE HINTERLAND AND THE RURAL DEVELOPMENT AREA Reporter: Janet M McNair MA(Hons) MPhil MRTPI File reference: IQD/2/270/7 Dates of the Inquiry: 14 April 2004 to 20 July 2004 CONTENTS VOLUME 3 Abbreviations The A96 Corridor Chapter 24 Land north and east of Balloch 24.1 Land between Balloch and Balmachree 24.2 Land at Lower Cullernie Farm Chapter 25 Inverness Airport and Dalcross Industrial Estate 25.1 Inverness Airport Economic Development Initiative 25.2 Airport Safeguarding 25.3 Extension to Dalcross Industrial Estate Chapter 26 Former fabrication yard at Ardersier Chapter 27 Morayhill Chapter 28 Lochside The Hinterland Chapter 29 Housing in the Countryside in the Hinterland 29.1 Background and context 29.2 objections to the local plan’s approach to individual and dispersed houses in the countryside in the Hinterland Objections relating to locations listed in Policy 6:1 29.3 Upper Myrtlefield 29.4 Cabrich 29.5 Easter Clunes 29.6 Culburnie 29.7 Ardendrain 29.8 Balnafoich 29.9 Daviot East 29.10 Leanach 29.11 Lentran House 29.12 Nairnside 29.13 Scaniport Objections relating to locations not listed in Policy 6.1 29.14 Blackpark Farm 29.15 Beauly Barnyards 29.16 Achmony, Balchraggan, Balmacaan, Bunloit, Drumbuie and Strone Chapter 30 Objections Regarding Settlement Expansion Rate in the Hinterland Chapter 31 Local centres in the Hinterland 31.1 Beauly 31.2 Drumnadrochit Chapter 32 Key Villages in the Hinterland -

Kirkandrews on Esk: Introduction1

Victoria County History of Cumbria Project: Work in Progress Interim Draft [Note: This is an incomplete, interim draft and should not be cited without first consulting the VCH Cumbria project: for contact details, see http://www.cumbriacountyhistory.org.uk/] Parish/township: KIRKANDREWS ON ESK Author: Fay V. Winkworth Date of draft: January 2013 KIRKANDREWS ON ESK: INTRODUCTION1 1. Description and location Kirkandrews on Esk is a large rural, sparsely populated parish in the north west of Cumbria bordering on Scotland. It extends nearly 10 miles in a north-east direction from the Solway Firth, with an average breadth of 3 miles. It comprised 10,891 acres (4,407 ha) in 1864 2 and 11,124 acres (4,502 ha) in 1938. 3 Originally part of the barony of Liddel, its history is closely linked with the neighbouring parish of Arthuret. The nearest town is Longtown (just across the River Esk in Arthuret parish). Kirkandrews on Esk, named after the church of St. Andrews 4, lies about 11 miles north of Carlisle. This parish is separated from Scotland by the rivers Sark and Liddel as well as the Scotsdike, a mound of earth erected in 1552 to divide the English Debatable lands from the Scottish. It is bounded on the south and east by Arthuret and Rockcliffe parishes and on the north east by Nicholforest, formerly a chapelry within Kirkandrews which became a separate ecclesiastical parish in 1744. The border with Arthuret is marked by the River Esk and the Carwinley burn. 1 The author thanks the following for their assistance during the preparation of this article: Ian Winkworth, Richard Brockington, William Bundred, Chairman of Kirkandrews Parish Council, Gillian Massiah, publicity officer Kirkandrews on Esk church, Ivor Gray and local residents of Kirkandrews on Esk, David Grisenthwaite for his detailed information on buses in this parish; David Bowcock, Tom Robson and the staff of Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle; Stephen White at Carlisle Central Library.