Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diet Breadth Affects Bacterial Identity but Not Diversity in the Pollen

insects Article Diet Breadth Affects Bacterial Identity but Not Diversity in the Pollen Provisions of Closely Related Polylectic and Oligolectic Bees Jason A. Rothman 1,2 , Diana L. Cox-Foster 3,* , Corey Andrikopoulos 3,4 and Quinn S. McFrederick 2,* 1 Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, 900 University Avenue, Riverside, CA 92521, USA 3 USDA-ARS Pollinating Insect-Biology, Management, and Systematics Research, Logan, UT 84322, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Biology, Utah State University, UMC5310, Logan, UT 84322, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.L.C.-F.); [email protected] (Q.S.M.) Received: 28 July 2020; Accepted: 17 September 2020; Published: 20 September 2020 Simple Summary: Solitary bees are important pollinators in managed and wild ecosystems. Across the bee phylogeny, bees may forage on a single species of plant, few plant species, or a broad diversity of plants. During foraging, these bees are often exposed to microbes, and in turn, may inoculate the brood cell and pollen provision of their offspring with these microbes. It is becoming evident that pollen-associated microbes are important to bee health, but it is not known how diet breadth impacts bees’ exposure to microbes. In this study, we collected pollen provisions from the bees Osmia lignaria and Osmia ribifloris at four different sites, then characterized the bacterial populations within the pollen provisions with 16S rRNA gene sequencing. We found that diet breadth did not have large effects on the bacteria found in the pollen provisions. -

The Oligolectic Bee Osmia Brevis Sonicates Penstemon Flowers for Pollen: a Newly Documented Behavior for the Megachilidae

Apidologie (2014) 45:678--684 Original article © INRA, Dffi and Springer-Verlag France, 2014 DOl: 10.10071s13592-014-0286-1 This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. The oligolectic bee Osmia brevis sonicates Penstemon flowers for pollen: a newly documented behavior for the Megachilidae James H. CANE USDA-ARS Pollinating Insect Research Unit, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5310, USA Received 7 December 2013 -Revised 21 February 2014- Accepted 2 April2014 Abstract - Flowers with poricidally dehiscent anthers are typically nectarless but are avidly visited and often solely pollinated by bees that sonicate the flowers to harvest pollen. Sonication results from shivering the thoracic flight muscles. Honey bees (Apis) and the 4,000+ species of Megachilidae are enigmatic in their seeming inability to sonicate flowers. The oligolectic megachilid bee Osmia brevis was found audibly sonicating two of its beardtongue pollen hosts, Penstemon radicosus and P. cyananthus. The bees' high-pitched sonication sequences are readily distinguishable from flight sounds in audiospectrograms, as well as sounds that result from anther rasping. Instead, floral sonication by 0. brevis resembles the familiar sounds of bumblebees buzzing, in this case while visiting P. strictus flowers. Apiformes I Megachilidae I buzz pollination I Penstemon I noral sonication I pollen foraging I porose anthers 1. INTRODUCTION blebees, are known to sonicate these poricidal anthers, as well as cones of introrse anthers, to The anthers of many species of flowering enhance their acquisition of pollen (Buchmann plants do not freely shed their pollen, but rather 1985; Buchmann 1983; De Luca and Vallejo dehisce pollen through terminal pores, slits, or Marin 2013). -

Conservation and Management of NORTH AMERICAN MASON BEES

Conservation and Management of NORTH AMERICAN MASON BEES Bruce E. Young Dale F. Schweitzer Nicole A. Sears Margaret F. Ormes Arlington, VA www.natureserve.org September 2015 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). This report was produced in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Citation: Young, B. E., D. F. Schweitzer, N. A. Sears, and M. F. Ormes. 2015. Conservation and Management of North American Mason Bees. 21 pp. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. © NatureServe 2015 Cover photos: Osmia sp. / Rollin Coville Bee block / Matthew Shepherd, The Xerces Society Osmia coloradensis / Rollin Coville NatureServe 4600 N. Fairfax Dr., 7th Floor Arlington, VA 22203 703-908-1800 www.natureserve.org EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document provides a brief overview of the diversity, natural history, conservation status, and management of North American mason bees. Mason bees are stingless, solitary bees. They are well known for being efficient pollinators, making them increasingly important components of our ecosystems in light of ongoing declines of honey bees and native pollinators. Although some species remain abundant and widespread, 27% of the 139 native species in North America are at risk, including 14 that have not been recorded for several decades. Threats to mason bees include habitat loss and degradation, diseases, pesticides, climate change, and their intrinsic vulnerability to declines caused by a low reproductive rate and, in many species, small range sizes. Management and conservation recommendations center on protecting suitable nesting habitat where bees spend most of the year, as well as spring foraging habitat. Major recommendations are: • Protect nesting habitat, including dead sticks and wood, and rocky and sandy areas. -

(Megachilidae; Osmia) As Fruit Tree Pollinators Claudio Sedivy, Silvia Dorn

Towards a sustainable management of bees of the subgenus Osmia (Megachilidae; Osmia) as fruit tree pollinators Claudio Sedivy, Silvia Dorn To cite this version: Claudio Sedivy, Silvia Dorn. Towards a sustainable management of bees of the subgenus Osmia (Megachilidae; Osmia) as fruit tree pollinators. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2013, 45 (1), pp.88-105. 10.1007/s13592-013-0231-8. hal-01234708 HAL Id: hal-01234708 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01234708 Submitted on 27 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie (2014) 45:88–105 Review article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2013 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-013-0231-8 Towards a sustainable management of bees of the subgenus Osmia (Megachilidae; Osmia) as fruit tree pollinators Claudio SEDIVY, Silvia DORN ETH Zurich, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Applied Entomology, Schmelzbergstrasse 9/LFO, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland Received 31 January 2013 – Revised 14 June 2013 – Accepted 18 July 2013 Abstract – The limited pollination efficiency of honeybees (Apidae; Apis) for certain crop plants and, more recently, their global decline fostered commercial development of further bee species to complement crop pollination in agricultural systems. -

Simultaneous Percussion by the Larvae of a Stem-Nesting Solitary

JHR 81: 143–164 (2021) doi: 10.3897/jhr.81.61067 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://jhr.pensoft.net Simultaneous percussion by the larvae of a stem- nesting solitary bee – a collaborative defence strategy against parasitoid wasps? Andreas Müller1, Martin K. Obrist2 1 ETH Zurich, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Biocommunication and Entomology, Schmelzbergstrasse 9/ LFO, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland 2 Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, Biodiversity and Conservation Biol- ogy, 8903 Birmensdorf, Switzerland Corresponding author: Andreas Müller ([email protected]) Academic editor: Michael Ohl | Received 23 November 2020 | Accepted 7 February 2021 | Published 25 February 2021 http://zoobank.org/D10742E1-E988-40C1-ADF6-7F8EC24D6FC4 Citation: Müller A, Obrist MK (2021) Simultaneous percussion by the larvae of a stem-nesting solitary bee – a collaborative defence strategy against parasitoid wasps? Journal of Hymenoptera Research 81: 143–164. https://doi. org/10.3897/jhr.81.61067 Abstract Disturbance sounds to deter antagonists are widespread among insects but have never been recorded for the larvae of bees. Here, we report on the production of disturbance sounds by the postdefecating larva (“prepupa”) of the Palaearctic osmiine bee Hoplitis (Alcidamea) tridentata, which constructs linear series of brood cells in excavated burrows in pithy plant stems. Upon disturbance, the prepupa produces two types of sounds, one of which can be heard up to a distance of 2–3 m (“stroking sounds”), whereas the other is scarcely audible by bare ear (“tapping sounds”). To produce the stroking sounds, the prepupa rapidly pulls a horseshoe-shaped callosity around the anus one to five times in quick succession over the cocoon wall before it starts to produce tapping sounds by knocking a triangularly shaped callosity on the clypeus against the cocoon wall in long uninterrupted series of one to four knocks per second. -

Osmia Lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) Produce Larger and Heavier 4 Blueberries Than Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) 5

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.28.176396; this version posted June 29, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 2 Short Communication 3 Osmia lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) produce larger and heavier 4 blueberries than honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) 5 6 Christine Cairns Fortuin, Kamal JK Gandhi 7 8 D.B. Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, 180 E Green Street, University 9 of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 10 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.28.176396; this version posted June 29, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 11 12 Abstract 13 Fruit set, berry size, and berry weight were assessed for pollination by the solitary bee 14 Osmia lignaria (Say) in caged rabbiteye blueberries (Vaccinium ashei Reade, Ericales : 15 Ericaceae), and compared to that of uncaged rabbiteye blueberries which were 16 pollinated largely by honey bees (Apis mellifera L). O. linaria produced berries that 17 were 1.6mm larger in diameter and 0.45g heavier than uncaged blueberries. Fruit set 18 was 40% higher in uncaged blueberries. This suggests that Osmia bees can produce 19 larger and heavier berry fruit, but O. -

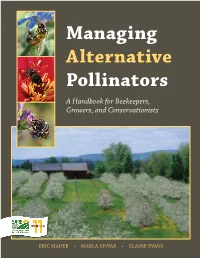

Managing-Alternative-Pollinators.Pdf

Managing Alternative Pollinators A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists ERIC MADER • MARLA SPIVAK • ELAINE EVANS Fair Use of this PDF file of Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, NRAES-186 By Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans Co-published by SARE and NRAES, February 2010 You can print copies of the PDF pages for personal use. If a complete copy is needed, we encourage you to purchase a copy as described below. Pages can be printed and copied for educational use. The book, authors, SARE, and NRAES should be acknowledged. Here is a sample acknowledgment: ----From Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, by Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans, and co- published by SARE and NRAES.---- No use of the PDF should diminish the marketability of the printed version. If you have questions about fair use of this PDF, contact NRAES. Purchasing the Book You can purchase printed copies on NRAES secure web site, www.nraes.org, or by calling (607) 255-7654. The book can also be purchased from SARE, visit www.sare.org. The list price is $28.00 plus shipping and handling. Quantity discounts are available. SARE and NRAES discount schedules differ. NRAES PO Box 4557 Ithaca, NY 14852-4557 Phone: (607) 255-7654 Fax: (607) 254-8770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nraes.org SARE 1122 Patapsco Building University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-6715 (301) 405-8020 (301) 405-7711 – Fax www.sare.org More information on SARE and NRAES is included at the end of this PDF. -

Towards Sustainable Crop Pollination Services Measures at Field, Farm and Landscape Scales

EXTENSION OF KNOWLEDGE BASE ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT CAPACITY BUILDING MAINSTREAMING TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE CROP POLLINATION SERVICES MEASURES AT FIELD, FARM AND LANDSCAPE SCALES POLLINATION SERVICES FOR SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE POLLINATION SERVICES FOR SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE CROP POLLINATION SERVICES MEASURES AT FIELD, FARM AND LANDSCAPE SCALES B. Gemmill-Herren, N. Azzu, A. Bicksler, and A. Guidotti [eds.] FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS ROME, 2020 Required citation: FAO. 2020. Towards sustainable crop pollination services – Measures at field, farm and landscape scales. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/ca8965en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-132578-0 © FAO, 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. -

Phylogenetic Systematics and the Evolution of Nesting

PHYLOGENETIC SYSTEMATICS AND THE EVOLUTION OF NESTING BEHAVIOR, HOST-PLANT PREFERENCE, AND CLEPTOPARASITISM IN THE BEE FAMILY MEGACHILIDAE (HYMENOPTERA, APOIDEA) A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jessica Randi Litman January 2012 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © 2012 Jessica Randi Litman ! PHYLOGENETIC SYSTEMATICS AND THE EVOLUTION OF NESTING BEHAVIOR, HOST-PLANT PREFERENCE, AND CLEPTOPARASITISM IN THE BEE FAMILY MEGACHILIDAE (HYMENOPTERA, APOIDEA) Jessica Randi Litman, Ph.D. Cornell University 2012 Members of the bee family Megachilidae exhibit fascinating behavior related to nesting, floral preference, and cleptoparasitic strategy. In order to explore the evolution of these behaviors, I assembled a large, multi-locus molecular data set for the bee family Megachilidae and used maximum likelihood-, Bayesian-, and maximum parsimony-based analytical methods to trace the evolutionary history of the family. I present the first molecular-based phylogenetic hypotheses of relationships within Megachilidae and use biogeographic analyses, ancestral state reconstructions, and divergence dating and diversification rate analyses to date the antiquity of Megachilidae and to explore patterns of diversification, nesting behavior and floral preferences in the family. I find that two ancient lineages of megachilid bees exhibit behavior and biology which reflect those of the earliest bees: they are solitary, restricted to deserts, build unlined -

Pollen Use by Osmia Lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in Highbush Blueberry Fields

Copyedited by: OUP Annals of the Entomological Society of America, XX(X), 2018, 1–6 doi: 10.1093/aesa/say028 Research Research Pollen Use by Osmia lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in Highbush Blueberry Fields Mario S. Pinilla-Gallego1,2,4 and Rufus Isaacs1,3 1Department of Entomology, Michigan State University, 578 Wilson Road, East Lansing, MI 48824, 2Applied Ecology Department, North Carolina State University, Campus Box 7617, 100 Brooks Avenue, Raleigh, NC 27607-7150, 3Ecology, Evolutionary Biology, and Behavior Program, Michigan State University, 103 Giltner Hall, 293 Farm Lane, East Lansing, MI 48824, 4Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Subject Editor: Allen Szalanski Received 8 May 2018; Editorial decision 14 July 2018 Abstract The blue orchard bee, Osmia lignaria (Say) (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae), is an alternative managed pollinator of rosaceous tree-crops, and potentially could be used for blueberry (Ericaceae) pollination. However, the floral preferences of this species for other types of flowers could prevent them from visiting blueberry flowers when alternative forage is available. To evaluate O. lignaria suitability for pollination of commercial blueberries in Michigan, we identified the main pollen sources in scopal loads and brood provisions, and determined the contribution of blueberry pollen to pollen collected by females nesting inside or at the border of a large blueberry field. Across two bloom seasons, we found that blueberry pollen was not the most abundant pollen type in either the scopal loads (≈6%) or the brood provisions (13–20%). Black cherry (Prunus serotina, Rosaceae), white clover (Trifolium repens, Fabaceae), and red clover (Trifolium pratese, Fabaceae) were the most abundant pollen types in the brood provisions. -

Biodiversity, Community Dynamics, and Novel Foraging Behaviors of a Rich Native Bee Fauna Across Habitats at Pinnacles National Park, California

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2016 Biodiversity, Community Dynamics, and Novel Foraging Behaviors of a Rich Native Bee Fauna Across Habitats at Pinnacles National Park, California Joan M. Meiners Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Meiners, Joan M., "Biodiversity, Community Dynamics, and Novel Foraging Behaviors of a Rich Native Bee Fauna Across Habitats at Pinnacles National Park, California" (2016). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4877. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4877 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BIODIVERSITY, COMMUNITY DYNAMICS, AND NOVEL FORAGING BEHAVIORS OF A RICH NATIVE BEE FAUNA ACROSS HABITATS AT PINNACLES NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA by Joan M. Meiners A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Ecology Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Dr. Edward W. Evans Dr. Terry L. Griswold Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Dr.Eugene W. Schupp Dr. Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2016 ii Copyright © Joan M. Meiners 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT BIODIVERSITY, COMMUNITY DYNAMICS, AND NOVEL FORAGING BEHAVIORS OF A RICH NATIVE BEE FAUNA ACROSS HABITATS AT PINNACLES NATIONAL PARK, CALIFORNIA by Joan M. -

The Status of the Red Mason Bee in the Orchards of Ankara and Çankırı Provinces, Turkey1

Türk. entomol. derg., 2020, 44 (2): 249-258 ISSN 1010-6960 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16970/entoted.651043 E-ISSN 2536-491X Original article (Orijinal araştırma) The status of the red mason bee in the orchards of Ankara and Çankırı Provinces, Turkey1 Kırmızı duvarcı arısının Ankara ve Çankırı (Türkiye) illerinin meyve bahçelerindeki durumu Yasemin GÜLER2* Abstract Research on the red mason bee, Osmia bicornis (L., 1758) (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae), which is an important pollinator particularly for stone fruits, in Turkey is limited to the last decade. After the first report in sweet cherry orchards of Afyonkarahisar, this study aimed to determine the presence and the density of the red mason bee and to collect data on its nesting biology between 2014 and 2016 in the mixed orchards of Ankara and Çankırı Provinces. Although the red mason bee was detected in almost all orchards sampled using the Malaise trap, the nesting activity was recorded in only four orchards in 2014 and 2015. Reeds with an inner diameter of 6-9 mm and a length of 15-25 cm were used as the artificial trap-nests. It was determined that the percentage of the nesting success varies between 6 and 48%. The cocoons that originated from the nests were placed in the incubator to stimulate diapause. Then, the temperature of the incubator was gradually increased to complete the life cycle of the species with starting the bud stage of stone fruits in early spring. Consequently, the emergence rates of the adults from the 135 cocoons collected in 2014 were 36 to 95%.