Pollen Use by Osmia Lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in Highbush Blueberry Fields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diet Breadth Affects Bacterial Identity but Not Diversity in the Pollen

insects Article Diet Breadth Affects Bacterial Identity but Not Diversity in the Pollen Provisions of Closely Related Polylectic and Oligolectic Bees Jason A. Rothman 1,2 , Diana L. Cox-Foster 3,* , Corey Andrikopoulos 3,4 and Quinn S. McFrederick 2,* 1 Department of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, 900 University Avenue, Riverside, CA 92521, USA 3 USDA-ARS Pollinating Insect-Biology, Management, and Systematics Research, Logan, UT 84322, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Biology, Utah State University, UMC5310, Logan, UT 84322, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.L.C.-F.); [email protected] (Q.S.M.) Received: 28 July 2020; Accepted: 17 September 2020; Published: 20 September 2020 Simple Summary: Solitary bees are important pollinators in managed and wild ecosystems. Across the bee phylogeny, bees may forage on a single species of plant, few plant species, or a broad diversity of plants. During foraging, these bees are often exposed to microbes, and in turn, may inoculate the brood cell and pollen provision of their offspring with these microbes. It is becoming evident that pollen-associated microbes are important to bee health, but it is not known how diet breadth impacts bees’ exposure to microbes. In this study, we collected pollen provisions from the bees Osmia lignaria and Osmia ribifloris at four different sites, then characterized the bacterial populations within the pollen provisions with 16S rRNA gene sequencing. We found that diet breadth did not have large effects on the bacteria found in the pollen provisions. -

The Oligolectic Bee Osmia Brevis Sonicates Penstemon Flowers for Pollen: a Newly Documented Behavior for the Megachilidae

Apidologie (2014) 45:678--684 Original article © INRA, Dffi and Springer-Verlag France, 2014 DOl: 10.10071s13592-014-0286-1 This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. The oligolectic bee Osmia brevis sonicates Penstemon flowers for pollen: a newly documented behavior for the Megachilidae James H. CANE USDA-ARS Pollinating Insect Research Unit, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5310, USA Received 7 December 2013 -Revised 21 February 2014- Accepted 2 April2014 Abstract - Flowers with poricidally dehiscent anthers are typically nectarless but are avidly visited and often solely pollinated by bees that sonicate the flowers to harvest pollen. Sonication results from shivering the thoracic flight muscles. Honey bees (Apis) and the 4,000+ species of Megachilidae are enigmatic in their seeming inability to sonicate flowers. The oligolectic megachilid bee Osmia brevis was found audibly sonicating two of its beardtongue pollen hosts, Penstemon radicosus and P. cyananthus. The bees' high-pitched sonication sequences are readily distinguishable from flight sounds in audiospectrograms, as well as sounds that result from anther rasping. Instead, floral sonication by 0. brevis resembles the familiar sounds of bumblebees buzzing, in this case while visiting P. strictus flowers. Apiformes I Megachilidae I buzz pollination I Penstemon I noral sonication I pollen foraging I porose anthers 1. INTRODUCTION blebees, are known to sonicate these poricidal anthers, as well as cones of introrse anthers, to The anthers of many species of flowering enhance their acquisition of pollen (Buchmann plants do not freely shed their pollen, but rather 1985; Buchmann 1983; De Luca and Vallejo dehisce pollen through terminal pores, slits, or Marin 2013). -

Floral Guilds of Bees in Sagebrush Steppe: Comparing Bee Usage Of

ABSTRACT: Healthy plant communities of the American sagebrush steppe consist of mostly wind-polli- • nated shrubs and grasses interspersed with a diverse mix of mostly spring-blooming, herbaceous perennial wildflowers. Native, nonsocial bees are their common floral visitors, but their floral associations and abundances are poorly known. Extrapolating from the few available pollination studies, bees are the primary pollinators needed for seed production. Bees, therefore, will underpin the success of ambitious seeding efforts to restore native forbs to impoverished sagebrush steppe communities following vast Floral Guilds of wildfires. This study quantitatively characterized the floral guilds of 17 prevalent wildflower species of the Great Basin that are, or could be, available for restoration seed mixes. More than 3800 bees repre- senting >170 species were sampled from >35,000 plants. Species of Osmia, Andrena, Bombus, Eucera, Bees in Sagebrush Halictus, and Lasioglossum bees prevailed. The most thoroughly collected floral guilds, at Balsamorhiza sagittata and Astragalus filipes, comprised 76 and 85 native bee species, respectively. Pollen-specialists Steppe: Comparing dominated guilds at Lomatium dissectum, Penstemon speciosus, and several congenerics. In contrast, the two native wildflowers used most often in sagebrush steppe seeding mixes—Achillea millefolium and Linum lewisii—attracted the fewest bees, most of them unimportant in the other floral guilds. Suc- Bee Usage of cessfully seeding more of the other wildflowers studied here would greatly improve degraded sagebrush Wildflowers steppe for its diverse native bee communities. Index terms: Apoidea, Asteraceae, Great Basin, oligolecty, restoration Available for Postfire INTRODUCTION twice a decade (Whisenant 1990). Massive Restoration wildfires are burning record acreages of the The American sagebrush steppe grows American West; two fires in 2007 together across the basins and foothills over much burned >500,000 ha of shrub-steppe and 1,3 James H. -

Sources and Frequency of Brood Loss in Solitary Bees

Apidologie Original Article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France SAS, part of Springer Nature, 2019 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-019-00663-2 Sources and frequency of brood loss in solitary bees 1 2 Robert L. MINCKLEY , Bryan N. DANFORTH 1Department of Biology, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY 14620, USA 2Department of Entomology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA Received4February2019– Revised 17 April 2019 – Accepted 4 June 2019 Abstract – We surveyed the literature for reports of parasites, predators, and other associates of the brood found in the nests of solitary bees. Studies were included in this survey if they reported the contents of all the bee brood cells that they examined. The natural enemies of solitary bees represented in the studies included here were taxonomically diverse. Although a few studies report high loss of solitary bee brood to a species-rich set of natural enemies, most studies report losses of less than 20% to few natural enemies. Brood parasitic bees are the greatest source of mortality for immatures of pollen-collecting solitary bees followed by meloid beetles (Meloidae), beeflies (Bombyliidae), and clerid beetles (Cleridae). Most groups, however, are reported from only a few host species and attack a low proportion of brood cells. Mortality due to unknown causes is also common. The suite of natural enemies that attack ground- and cavity-nesting solitary bees is very different. The cavity-nesting species have higher reported mortality due to unknown causes perhaps related to how nests are manipulated and handled by researchers. brood parasite / predator / cavity-nesting bees / ground-nesting bees / meta-analysis 1. -

Conservation and Management of NORTH AMERICAN MASON BEES

Conservation and Management of NORTH AMERICAN MASON BEES Bruce E. Young Dale F. Schweitzer Nicole A. Sears Margaret F. Ormes Arlington, VA www.natureserve.org September 2015 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). This report was produced in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Citation: Young, B. E., D. F. Schweitzer, N. A. Sears, and M. F. Ormes. 2015. Conservation and Management of North American Mason Bees. 21 pp. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. © NatureServe 2015 Cover photos: Osmia sp. / Rollin Coville Bee block / Matthew Shepherd, The Xerces Society Osmia coloradensis / Rollin Coville NatureServe 4600 N. Fairfax Dr., 7th Floor Arlington, VA 22203 703-908-1800 www.natureserve.org EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document provides a brief overview of the diversity, natural history, conservation status, and management of North American mason bees. Mason bees are stingless, solitary bees. They are well known for being efficient pollinators, making them increasingly important components of our ecosystems in light of ongoing declines of honey bees and native pollinators. Although some species remain abundant and widespread, 27% of the 139 native species in North America are at risk, including 14 that have not been recorded for several decades. Threats to mason bees include habitat loss and degradation, diseases, pesticides, climate change, and their intrinsic vulnerability to declines caused by a low reproductive rate and, in many species, small range sizes. Management and conservation recommendations center on protecting suitable nesting habitat where bees spend most of the year, as well as spring foraging habitat. Major recommendations are: • Protect nesting habitat, including dead sticks and wood, and rocky and sandy areas. -

(Megachilidae; Osmia) As Fruit Tree Pollinators Claudio Sedivy, Silvia Dorn

Towards a sustainable management of bees of the subgenus Osmia (Megachilidae; Osmia) as fruit tree pollinators Claudio Sedivy, Silvia Dorn To cite this version: Claudio Sedivy, Silvia Dorn. Towards a sustainable management of bees of the subgenus Osmia (Megachilidae; Osmia) as fruit tree pollinators. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2013, 45 (1), pp.88-105. 10.1007/s13592-013-0231-8. hal-01234708 HAL Id: hal-01234708 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01234708 Submitted on 27 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie (2014) 45:88–105 Review article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2013 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-013-0231-8 Towards a sustainable management of bees of the subgenus Osmia (Megachilidae; Osmia) as fruit tree pollinators Claudio SEDIVY, Silvia DORN ETH Zurich, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Applied Entomology, Schmelzbergstrasse 9/LFO, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland Received 31 January 2013 – Revised 14 June 2013 – Accepted 18 July 2013 Abstract – The limited pollination efficiency of honeybees (Apidae; Apis) for certain crop plants and, more recently, their global decline fostered commercial development of further bee species to complement crop pollination in agricultural systems. -

An Inventory of Native Bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes)

An Inventory of Native Bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes) in the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming BY David J. Drons A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Major in Plant Science South Dakota State University 2012 ii An Inventory of Native Bees (Hymenoptera: Apiformes) in the Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming This thesis is approved as a credible and independent investigation by a candidate for the Master of Plant Science degree and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this thesis does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. __________________________________ Dr. Paul J. Johnson Thesis Advisor Date __________________________________ Dr. Doug Malo Assistant Plant Date Science Department Head iii Acknowledgements I (the author) would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Paul J. Johnson and my committee members Dr. Carter Johnson and Dr. Alyssa Gallant for their guidance. I would also like to thank the South Dakota Game Fish and Parks department for funding this important project through the State Wildlife Grants program (grant #T2-6-R-1, Study #2447), and Custer State Park assisting with housing during the field seasons. A special thank you to taxonomists who helped with bee identifications: Dr. Terry Griswold, Jonathan Koch, and others from the USDA Logan bee lab; Karen Witherhill of the Sivelletta lab at the University of New Mexico; Dr. Laurence Packer, Shelia Dumesh, and Nicholai de Silva from York University; Rita Velez from South Dakota State University, and Jelle Devalez a visiting scientist at the US Geological Survey. -

Simultaneous Percussion by the Larvae of a Stem-Nesting Solitary

JHR 81: 143–164 (2021) doi: 10.3897/jhr.81.61067 RESEARCH ARTICLE https://jhr.pensoft.net Simultaneous percussion by the larvae of a stem- nesting solitary bee – a collaborative defence strategy against parasitoid wasps? Andreas Müller1, Martin K. Obrist2 1 ETH Zurich, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Biocommunication and Entomology, Schmelzbergstrasse 9/ LFO, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland 2 Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, Biodiversity and Conservation Biol- ogy, 8903 Birmensdorf, Switzerland Corresponding author: Andreas Müller ([email protected]) Academic editor: Michael Ohl | Received 23 November 2020 | Accepted 7 February 2021 | Published 25 February 2021 http://zoobank.org/D10742E1-E988-40C1-ADF6-7F8EC24D6FC4 Citation: Müller A, Obrist MK (2021) Simultaneous percussion by the larvae of a stem-nesting solitary bee – a collaborative defence strategy against parasitoid wasps? Journal of Hymenoptera Research 81: 143–164. https://doi. org/10.3897/jhr.81.61067 Abstract Disturbance sounds to deter antagonists are widespread among insects but have never been recorded for the larvae of bees. Here, we report on the production of disturbance sounds by the postdefecating larva (“prepupa”) of the Palaearctic osmiine bee Hoplitis (Alcidamea) tridentata, which constructs linear series of brood cells in excavated burrows in pithy plant stems. Upon disturbance, the prepupa produces two types of sounds, one of which can be heard up to a distance of 2–3 m (“stroking sounds”), whereas the other is scarcely audible by bare ear (“tapping sounds”). To produce the stroking sounds, the prepupa rapidly pulls a horseshoe-shaped callosity around the anus one to five times in quick succession over the cocoon wall before it starts to produce tapping sounds by knocking a triangularly shaped callosity on the clypeus against the cocoon wall in long uninterrupted series of one to four knocks per second. -

Osmia Lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) Produce Larger and Heavier 4 Blueberries Than Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) 5

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.28.176396; this version posted June 29, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 2 Short Communication 3 Osmia lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) produce larger and heavier 4 blueberries than honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) 5 6 Christine Cairns Fortuin, Kamal JK Gandhi 7 8 D.B. Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, 180 E Green Street, University 9 of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 10 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.28.176396; this version posted June 29, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 11 12 Abstract 13 Fruit set, berry size, and berry weight were assessed for pollination by the solitary bee 14 Osmia lignaria (Say) in caged rabbiteye blueberries (Vaccinium ashei Reade, Ericales : 15 Ericaceae), and compared to that of uncaged rabbiteye blueberries which were 16 pollinated largely by honey bees (Apis mellifera L). O. linaria produced berries that 17 were 1.6mm larger in diameter and 0.45g heavier than uncaged blueberries. Fruit set 18 was 40% higher in uncaged blueberries. This suggests that Osmia bees can produce 19 larger and heavier berry fruit, but O. -

The Biology and External Morphology of Bees

3?00( The Biology and External Morphology of Bees With a Synopsis of the Genera of Northwestern America Agricultural Experiment Station v" Oregon State University V Corvallis Northwestern America as interpreted for laxonomic synopses. AUTHORS: W. P. Stephen is a professor of entomology at Oregon State University, Corval- lis; and G. E. Bohart and P. F. Torchio are United States Department of Agriculture entomolo- gists stationed at Utah State University, Logan. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The research on which this bulletin is based was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grants Nos. 3835 and 3657. Since this publication is largely a review and synthesis of published information, the authors are indebted primarily to a host of sci- entists who have recorded their observations of bees. In most cases, they are credited with specific observations and interpretations. However, information deemed to be common knowledge is pre- sented without reference as to source. For a number of items of unpublished information, the generosity of several co-workers is ac- knowledged. They include Jerome G. Rozen, Jr., Charles Osgood, Glenn Hackwell, Elbert Jay- cox, Siavosh Tirgari, and Gordon Hobbs. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Leland Chandler and Dr. Jerome G. Rozen, Jr., for reviewing the manuscript and for many helpful suggestions. Most of the drawings were prepared by Mrs. Thelwyn Koontz. The sources of many of the fig- ures are given at the end of the Literature Cited section on page 130. The cover drawing is by Virginia Taylor. The Biology and External Morphology of Bees ^ Published by the Agricultural Experiment Station and printed by the Department of Printing, Ore- gon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, 1969. -

Minnesota State Records for Osmia Georgica, Megachile Inimica, And

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 53 Numbers 3 & 4 - Fall/Winter 2020 Numbers 3 & Article 6 4 - Fall/Winter 2020 December 2020 Minnesota State Records for Osmia georgica, Megachile inimica, and Megachile frugalis (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae), Including a New Nest Description for Megachile frugalis Compared with Other Species in the Subgenus Sayapis Colleen D. Satyshur Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, University of Minnesota, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, Saint Paul, MN 55108, USA, [email protected] Thea A. Evans Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, University of Minnesota, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, Saint Paul, MN 55108, USA, [email protected] Britt M. Forsberg versity of Minnesota Extension, University of Minnesota, 135 Skok Hall, 2003 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA, [email protected] Robert B. Blair Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology, University of Minnesota, 135 Skok Hall, 2003 FUpperollow Bufor this andd Cir additionalcle, St. Paul, works MN at:55108, https:/ USA/scholar, [email protected]/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Satyshur, Colleen D.; Evans, Thea A.; Forsberg, Britt M.; and Blair, Robert B. 2020. "Minnesota State Records for Osmia georgica, Megachile inimica, and Megachile frugalis (Hymenoptera, Megachilidae), Including a New Nest Description for Megachile frugalis Compared with Other Species in the Subgenus Sayapis," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 53 (2) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol53/iss2/6 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. -

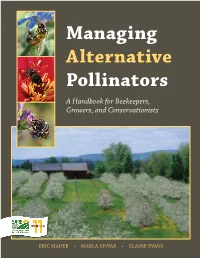

Managing-Alternative-Pollinators.Pdf

Managing Alternative Pollinators A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists ERIC MADER • MARLA SPIVAK • ELAINE EVANS Fair Use of this PDF file of Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, NRAES-186 By Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans Co-published by SARE and NRAES, February 2010 You can print copies of the PDF pages for personal use. If a complete copy is needed, we encourage you to purchase a copy as described below. Pages can be printed and copied for educational use. The book, authors, SARE, and NRAES should be acknowledged. Here is a sample acknowledgment: ----From Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists, SARE Handbook 11, by Eric Mader, Marla Spivak, and Elaine Evans, and co- published by SARE and NRAES.---- No use of the PDF should diminish the marketability of the printed version. If you have questions about fair use of this PDF, contact NRAES. Purchasing the Book You can purchase printed copies on NRAES secure web site, www.nraes.org, or by calling (607) 255-7654. The book can also be purchased from SARE, visit www.sare.org. The list price is $28.00 plus shipping and handling. Quantity discounts are available. SARE and NRAES discount schedules differ. NRAES PO Box 4557 Ithaca, NY 14852-4557 Phone: (607) 255-7654 Fax: (607) 254-8770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nraes.org SARE 1122 Patapsco Building University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-6715 (301) 405-8020 (301) 405-7711 – Fax www.sare.org More information on SARE and NRAES is included at the end of this PDF.