Cremation: History and Prevalence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 18 October 2018 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Caswell, E. and Roberts, B.W. (2018) 'Reassessing community cemeteries : cremation burials in Britain during the Middle Bronze Age (c. 16001150 cal BC).', Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society., 84 . pp. 329-357. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2018.9 Publisher's copyright statement: c The Prehistoric Society 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, page 1 of 29 © The Prehistoric Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

The Incorporation of Human Cremation Ashes Into Objects and Tattoos in Contemporary British Practices

Ashes to Art, Dust to Diamonds: The incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos in contemporary British practices Samantha McCormick A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Sociology August 2015 Declaration I declare that the work in this thesis was carried out in accordance with the requirements of the University’s regulations and Code of Practice for Research Degree Programmes and all the material provided in this thesis are original and have not been published elsewhere. I declare that while registered as a candidate for the University’s research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SINGED ………………………………… i ii Abstract This thesis examines the incorporation of human cremated remains into objects and tattoos in a range of contemporary practices in British society. Referred to collectively in this study as ‘ashes creations’, the practices explored in this research include human cremation ashes irreversibly incorporated or transformed into: jewellery, glassware, diamonds, paintings, tattoos, vinyl records, photograph frames, pottery, and mosaics. This research critically analyses the commissioning, production, and the lived experience of the incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos from the perspective of two groups of people who participate in these practices: people who have commissioned an ashes creations incorporating the cremation ashes of a loved one and people who make or sell ashes creations. -

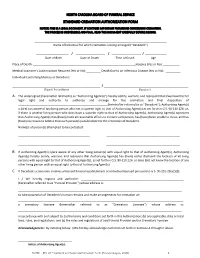

Standard Cremation Authorization Form

NORTH CAROLINA BOARD OF FUNERAL SERVICE STANDARD CREMATION AUTHORIZATION FORM NOTICE: THIS IS A LEGAL DOCUMENT. IT CONTAINS IMPORTANT PROVISIONS CONCERNING CREMATION. THE PROCESS IS IRREVERSIBLE AND FINAL. READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY BEFORE SIGNING. _________________________________________________________________________________ Name of Individual for which cremation is being arranged (“Decedent”) ____________________ / __________________ / __________________ / _____________ Date of Birth Date of Death Time of Death Age Place of Death: _______________________________________________________________Hospice (Yes or No): __________ Medical Examiner’s Authorization Required (Yes or No):_________ Death Due to an Infectious Disease (Yes or No): _________ Individual Confirming Identity of Decedent: ______________________________________________________ / ____________________________________________________ (Typed / Printed Name) (Signature) A. The undersigned (hereinafter referred to as "Authorizing Agent{s}”) hereby certify, warrant, and represent that I/we have the full legal right and authority to authorize and arrange for the cremation and final disposition of _______________________________________________________(hereinafter referred to as "Decedent"); Authorizing Agent(s) is (are) not aware of any living person who has a superior right to that of Authorizing Agent(s) as set forth in G.S. 90-210.124; or, if there is another living person who does have a superior right to that of Authorizing Agent(s), Authorizing Agent(s) represent that -

Architecture of Afterlife: Future Cemetery in Metropolis

ARCHITECTURE OF AFTERLIFE: FUTURE CEMETERY IN METROPOLIS A DARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARCHITECTURE MAY 2017 BY SHIYU SONG DArch Committee: Joyce Noe, Chairperson William Chapman Brian Takahashi Key Words: Conventional Cemetery, Contemporary Cemetery, Future Cemetery, High-technology Innovation Architecture of Afterlife: Future Cemetery in Metropolis Shiyu Song April 2017 We certify that we have read this Doctorate Project and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Architecture in the School of Architecture, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Doctorate Project Committee ___________________________________ Joyce Noe ___________________________________ William Chapman ___________________________________ Brian Takahashi Acknowledgments I dedicate this thesis to everyone in my life. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Professor Joyce Noe, for her support, guidance and insight throughout this doctoral project. Many thanks to my wonderful committee members William Chapman and Brian Takahashi for their precious and valuable guidance and support. Salute to my dear professor Spencer Leineweber who inspires me in spirit and work ethic. Thanks to all the professors for your teaching and encouragement imparted on me throughout my years of study. After all these years of study, finally, I understand why we need to study and how important education is. Overall, this dissertation is an emotional research product. As an idealist, I choose this topic as a lesson for myself to understand life through death. The more I delve into the notion of death, the better I appreciate life itself, and knowing every individual human being is a bless; everyday is a present is my best learning outcome. -

Introduction Archaeologies of Cremation Howard Williams, Jessica I

Introduction Archaeologies of Cremation Howard Williams, Jessica I. Cerezo-Román, and Anna Wessman Williams, H., Cerezo-Román, J.I., and Wessman, A. (eds) 2017. Introduction: Archaeologies of Cremation, in J.I. Cerezo-Román, A. Wessman and H. Williams (eds) Cremation and the Archaeology of Death, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–24 Then the warriors began to kindle the greatest of funeral fires on the hill; woodsmoke ascended, dark over the flame, the soaring fire mingled with weeping – the raging wind subsided – until it had broken the body, hot at the heart. Depressed in soul, they lamented their grief, mourned the liege lord. Likewise the Geatish woman lamented for Beowulf, with bound hair, sang a sorrowful song, said often that she greatly feared evil days for herself, many slaughters, fear of the foe, humiliation and captivity. Heaven swallowed the smoke. Beowulf 3143–3155 (Owen-Crocker 2000: 91, 93) INTRODUCTION Four dramatic funerals punctuate the tenth- or eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf; two involve the burning of the dead. While a Christian work to its core, the poem draws upon far older stories and at its very conclusion the poet provides a striking vision of an early medieval open-air cremation ceremony. Having died by the fire and poisonous bite of a dragon dwelling in a stone mound, the king of the Geats is cremated with treasures: helmets, swords, and coats of mail (Owen-Crocker 2000: 89). Before the raising of a burial mound upon a headland overlooking the sea, Beowulf ’s cremation is a focus of more than personal loss by mourners. -

The Hundred Syllable Vajrasattva Mantra

The Hundred Syllable Vajrasattva Mantra. Dharmacārī Jayarava1 The Sanskrit version of the one hundred syllable Vajrasattva mantra in the Puja Book of the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (the FWBO) follows the edited text produced by Dharmacārin and Sanskritist Sthiramati (aka Dr. Andrew Skilton) in his article: The Vajrasattva Mantra: Notes on a Corrected Sanskrit Text. Sthiramati‟s original brief was to provide diacritical marks so that the Sanskrit words were spelled correctly. However he went beyond the scope of merely providing proper diacritics to discuss problems with the structure and spelling of the mantra after consulting a number of printed books and manuscripts in a variety of scripts and languages. Since the edited version produced by Sthiramati was adopted some 19 years ago, the problems with the older version used before that are less relevant to members of the Western Buddhist Order (WBO) except in one case which I discuss below.2 In this article I will offer a summary of the salient points of Sthiramati‟s lexical and grammatical analysis, along with my own glosses of the Sanskrit. By this means, I hope to create an annotated translation that lays open the Sanskrit to anyone who is interested. Sthiramati‟s interpretation differs in some important respects from the traditional Tibetan one, but does so in ways that help to make sense of the Sanskrit - for instance in several cases he suggests breaking a sandhi 3 one letter along in order to create a straightforward Sanskrit sentence that was otherwise obscured. In the second part of the article I will address the problem of errors in transmission and how these might have come about in the case of this mantra. -

Murakami Haruki's Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By

Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society By © 2019 Jacob Clements B.A. University of Northern Iowa, 2013 Submitted to the graduate degree program in East Asian Language and Cultures and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert ___________________________ Dr. Margaret Childs ___________________________ Dr. Ayako Mizumura Date Defended: 19 April 2019 The thesis committee for Jacob Clements certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Murakami Haruki’s Short Fiction and the Japanese Consumer Society _________________________ Chair: Dr. Elaine Gerbert Date Approved: 16 May 2019 ii Abstract This thesis seeks to describe the Japanese novelist Murakami Haruki’s continuing critique of Japan’s modern consumer-oriented society in his fiction. The first chapter provides a brief history of Japan’s consumer-oriented society, beginning with the Meiji Restoration and continuing to the 21st Century. A literature review of critical works on Murakami’s fiction, especially those on themes of identity and consumerism, makes up the second chapter. Finally, the third chapter introduces three of Murakami Haruki’s short stories. These short stories, though taken from three different periods of Murakami’s career, can be taken together to show a legacy of critiquing Japan’s consumer-oriented society. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Maggie Childs and Dr. Ayako Mizumura, for their guidance and support throughout my Master's degree process. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Elaine Gerbert her guidance throughout my degree and through the creation of this thesis. -

King David's City at Khirbet Qeiyafa

King David’s City at Khirbet Qeiyafa: Results of the Second Radiocarbon Dating Project Garfinkel, Y., Streit, K., Ganor, S., & Reimer, P. (2015). King David’s City at Khirbet Qeiyafa: Results of the Second Radiocarbon Dating Project. Radiocarbon, 57(5), 881-890. https://doi.org/10.2458/azu_rc.57.17961 Published in: Radiocarbon Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © The Authors, 2015 This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:02. Oct. 2021 Radiocarbon, Vol 57, Nr 5, 2015, p 881–890 DOI: 10.2458/azu_rc.57.17961 © 2015 by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona KING DAVID’S CITY AT KHIRBET QEIYAFA: RESULTS OF THE SECOND RADIOCAR- BON DATING PROJECT Yosef Garfinkel1,2 • Katharina Streit1 • Saar Ganor3 • Paula J Reimer4 ABSTRACT. -

Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans

3 (2016) Miscellaneous 1: A-V Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans TRAVIS D. WEBSTER Center for Traditional Vedanta, USA © 2016 Ruhr-Universität Bochum Entangled Religions 3 (2016) ISSN 2363-6696 http://dx.doi.org/10.13154/er.v3.2016.A–V Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans Proto-Indo-European Roots of the Vedic Aryans TRAVIS D. WEBSTER Center for Traditional Vedanta ABSTRACT Recent archaeological evidence and the comparative method of Indo-European historical linguistics now make it possible to reconstruct the Aryan migrations into India, two separate diffusions of which merge with elements of Harappan religion in Asko Parpola’s The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization (NY: Oxford University Press, 2015). This review of Parpola’s work emphasizes the acculturation of Rigvedic and Atharvavedic traditions as represented in the depiction of Vedic rites and worship of Indra and the Aśvins (Nāsatya). After identifying archaeological cultures prior to the breakup of Proto-Indo-European linguistic unity and demarcating the two branches of the Proto-Aryan community, the role of the Vrātyas leads back to mutual encounters with the Iranian Dāsas. KEY WORDS Asko Parpola; Aryan migrations; Vedic religion; Hinduism Introduction Despite the triumph of the world-religions paradigm from the late nineteenth century onwards, the fact remains that Indologists require more precise taxonomic nomenclature to make sense of their data. Although the Vedas are widely portrayed as the ‘Hindu scriptures’ and are indeed upheld as the sole arbiter of scriptural authority among Brahmins, for instance, the Vedic hymns actually play a very minor role in contemporary Indian religion. -

Case of Almaqah Temple of Yeha (Ethiopia)

International Journal of Management Volume 11, Issue 10, October 2020, pp. 1528-1536. Article ID: IJM_11_10_139 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJM?Volume=11&Issue=10 Journal Impact Factor (2020): 10.1471 (Calculated by GISI) www.jifactor.com ISSN Print: 0976-6502 and ISSN Online: 0976-6510 DOI: 10.34218/IJM.11.10.2020.139 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed ANCIENT CULTURAL LINKAGE OF ETHIOPIA WITH INDIA: CASE OF ALMAQAH TEMPLE OF YEHA (ETHIOPIA) Dr. Alok Kumar Professor, Jain University, Bangalore, India ABSTRACT This paper is an attempt to highlight ancient cultural linkage of Ethiopia with India and strong resemblances of cultural and religious practices of present orthodox Christian of Ethiopia with Hindus of India. This study also describes the claim of delegation of Indian experts that Yeha temple has been a Hindu (Jain) temple. The study was conducted by personal visit and observation at the excavation site and its museum, discussion with German expert and local community. Findings are based on observation and findings of joint Indian-Ethiopian team from New Delhi and Experts from Mekelle University which visited to study archeologist sites. The previous studies indicated that origin of Yeha civilization was Southern Arabia. The German Archeologist linked it to Sabaean culture. They called the structure as Sabaean Temple. But, the visit of team of Indo-Ethiopian expert to the excavation site disputed their claim. They linked it to Indian temples and found evidence of strong resemblance of present cultural practices of orthodox Christian with Indian Hindus. The inscriptions found at Almaqah temple of Yeha is of Brahmi script. -

Religions of the World Series Hinduism 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

RELIGIONS OF THE WORLD SERIES HINDUISM 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cybelle T Shattuck | 9780132662550 | | | | | Religions of the World Series Hinduism 1st edition PDF Book Focusing particularly on the modern period, it provides a valuable introduction to contemporary Hindu beliefs and practices and looks at the ways in which this religion is meeting the challenges of the modern world. A bit to in-depth for us. Similarly, Telugu -speaking priests from the Tirupati region have been imported to serve at temples such as the historically important Ganesha temple, constructed in Queens, New York, in — Sikhism 0. Their character differs markedly according to region, class, and the time at which emigration occurred. Overviews and lists. Stands Alone in its Embrace of Religion". Major religious groups and denominations 1. Signed out You have successfully signed out and will be required to sign back in should you need to download more resources. Published by Routledge The early 19th-century Sira Puranam , a biography of the Prophet Muhammad , is an excellent example. Sign In We're sorry! Worldwide percentage of Adherents by Religion, [1]. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Many Hindus are ready to accept the ethical teachings of the Gospels , particularly the Sermon on the Mount whose influence on Gandhi is well known , but reject the theological superstructure. This book covers almost all major areas of academic research on religion and could prove to be an inspiration for serious research on Hinduism. Hinduism and Christianity Relations between Hinduism and Christianity have been shaped by unequal balances of political power and cultural influence.