1 in Defiance of a Stylistic Stereotype: British Crematoria, Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 18 October 2018 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Caswell, E. and Roberts, B.W. (2018) 'Reassessing community cemeteries : cremation burials in Britain during the Middle Bronze Age (c. 16001150 cal BC).', Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society., 84 . pp. 329-357. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2018.9 Publisher's copyright statement: c The Prehistoric Society 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, page 1 of 29 © The Prehistoric Society. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Your Guide to Hospice Care If You Have an Emergency, Call Us Anytime, Day Or Night

Your guide to hospice care If you have an emergency, call us anytime, day or night. Our nurses are here 24/7 to assist you. Call us anytime you need us. If you are in pain, not comfortable, feeling stressed or just need to be reassured, call us — that is why we are here. We will help coordinate your care and ensure you receive services promptly and specifically targeted to meeting your goals and keeping you comfortable. Please call us before visiting the emergency room, seeing a physician or scheduling a test or procedure to determine if it will be covered as part of your hospice care. All services related to the terminal illness or related conditions need to be preapproved by the hospice provider, otherwise the patient will be financially responsible for those services. 3 Open a door to renewed hope When most people think of hospice, the word “hope” rarely comes to mind. Novant Health Hospice is working to change that perception. By definition, hope is the feeling that what is desired is also possible, or that events will turn out for the best. In hospice, we hear our patients and families hope for a positive outcome related to whatever circumstances they are experiencing. To us, hope for our patients means helping them live life to its fullest — spending quality time surrounded by those they love. We focus on going beyond meeting needs to creating special moments in the lives of our patients and their loved ones. We also help prepare family and friends for the loss of a loved one and help them deal with their grief through compassion, counseling and bereavement support. -

Crematoria Emissions and Air Quality Impacts

MARCH 2020 FIELD INQUIRY: CREMATORIA EMISSIONS AND AIR QUALITY IMPACTS Prepared by: Juliette O’Keeffe National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health PRIMARY INQUIRY A municipality received an application from a funeral home risks to nearby communities. This field inquiry therefore to install a cremator within their facility. Objections were focusses on crematoria-related air pollution and human received from nearby residents who were concerned about health risks. potential exposure to harmful emissions. A public health unit was contacted to help answer the following questions: METHODS 1. Do crematoria emit harmful pollutants? A rapid literature search was undertaken for articles related 2. Is there evidence of health impacts due to exposure to to health and air quality issues and their association with crematoria emissions? combustion processes in crematoria. Articles were identified 3. What is standard practice for siting of crematorium in using EBSCOhost (Biomedical Reference Collection: proximity to residential areas? Comprehensive, CINAHL Complete, GreenFILE, MEDLINE 4. What steps can be taken to minimize crematoria with Full Text, Urban Studies Abstract) and Google Scholar. emissions to reduce exposure risks? Terms used in the search included variants and Boolean operator combinations of (cremat* OR “funeral home”) AND BACKGROUND (health OR illness OR irrita* OR annoy* OR emission OR “air In Canada, preference for cremation over burial has been quality”). Inclusion criteria were publication date (no date increasing since the 1950s. The Cremation Association of restriction), English language, and human subjects. Google North America (CANA) estimated that in 2016 approximately was used to access relevant public agency websites and 70% of human remains in Canada were cremated, and this grey literature including Canadian public health documents may rise to about 80% in 2020.1,2 The increased demand for concerning cremation facilities and examples of current cremation services can only be met by constructing new practices elsewhere. -

The Incorporation of Human Cremation Ashes Into Objects and Tattoos in Contemporary British Practices

Ashes to Art, Dust to Diamonds: The incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos in contemporary British practices Samantha McCormick A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Sociology August 2015 Declaration I declare that the work in this thesis was carried out in accordance with the requirements of the University’s regulations and Code of Practice for Research Degree Programmes and all the material provided in this thesis are original and have not been published elsewhere. I declare that while registered as a candidate for the University’s research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SINGED ………………………………… i ii Abstract This thesis examines the incorporation of human cremated remains into objects and tattoos in a range of contemporary practices in British society. Referred to collectively in this study as ‘ashes creations’, the practices explored in this research include human cremation ashes irreversibly incorporated or transformed into: jewellery, glassware, diamonds, paintings, tattoos, vinyl records, photograph frames, pottery, and mosaics. This research critically analyses the commissioning, production, and the lived experience of the incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos from the perspective of two groups of people who participate in these practices: people who have commissioned an ashes creations incorporating the cremation ashes of a loved one and people who make or sell ashes creations. -

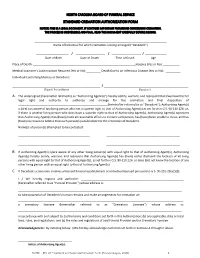

Standard Cremation Authorization Form

NORTH CAROLINA BOARD OF FUNERAL SERVICE STANDARD CREMATION AUTHORIZATION FORM NOTICE: THIS IS A LEGAL DOCUMENT. IT CONTAINS IMPORTANT PROVISIONS CONCERNING CREMATION. THE PROCESS IS IRREVERSIBLE AND FINAL. READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY BEFORE SIGNING. _________________________________________________________________________________ Name of Individual for which cremation is being arranged (“Decedent”) ____________________ / __________________ / __________________ / _____________ Date of Birth Date of Death Time of Death Age Place of Death: _______________________________________________________________Hospice (Yes or No): __________ Medical Examiner’s Authorization Required (Yes or No):_________ Death Due to an Infectious Disease (Yes or No): _________ Individual Confirming Identity of Decedent: ______________________________________________________ / ____________________________________________________ (Typed / Printed Name) (Signature) A. The undersigned (hereinafter referred to as "Authorizing Agent{s}”) hereby certify, warrant, and represent that I/we have the full legal right and authority to authorize and arrange for the cremation and final disposition of _______________________________________________________(hereinafter referred to as "Decedent"); Authorizing Agent(s) is (are) not aware of any living person who has a superior right to that of Authorizing Agent(s) as set forth in G.S. 90-210.124; or, if there is another living person who does have a superior right to that of Authorizing Agent(s), Authorizing Agent(s) represent that -

Architecture of Afterlife: Future Cemetery in Metropolis

ARCHITECTURE OF AFTERLIFE: FUTURE CEMETERY IN METROPOLIS A DARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARCHITECTURE MAY 2017 BY SHIYU SONG DArch Committee: Joyce Noe, Chairperson William Chapman Brian Takahashi Key Words: Conventional Cemetery, Contemporary Cemetery, Future Cemetery, High-technology Innovation Architecture of Afterlife: Future Cemetery in Metropolis Shiyu Song April 2017 We certify that we have read this Doctorate Project and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Architecture in the School of Architecture, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Doctorate Project Committee ___________________________________ Joyce Noe ___________________________________ William Chapman ___________________________________ Brian Takahashi Acknowledgments I dedicate this thesis to everyone in my life. I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Professor Joyce Noe, for her support, guidance and insight throughout this doctoral project. Many thanks to my wonderful committee members William Chapman and Brian Takahashi for their precious and valuable guidance and support. Salute to my dear professor Spencer Leineweber who inspires me in spirit and work ethic. Thanks to all the professors for your teaching and encouragement imparted on me throughout my years of study. After all these years of study, finally, I understand why we need to study and how important education is. Overall, this dissertation is an emotional research product. As an idealist, I choose this topic as a lesson for myself to understand life through death. The more I delve into the notion of death, the better I appreciate life itself, and knowing every individual human being is a bless; everyday is a present is my best learning outcome. -

Introduction Archaeologies of Cremation Howard Williams, Jessica I

Introduction Archaeologies of Cremation Howard Williams, Jessica I. Cerezo-Román, and Anna Wessman Williams, H., Cerezo-Román, J.I., and Wessman, A. (eds) 2017. Introduction: Archaeologies of Cremation, in J.I. Cerezo-Román, A. Wessman and H. Williams (eds) Cremation and the Archaeology of Death, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–24 Then the warriors began to kindle the greatest of funeral fires on the hill; woodsmoke ascended, dark over the flame, the soaring fire mingled with weeping – the raging wind subsided – until it had broken the body, hot at the heart. Depressed in soul, they lamented their grief, mourned the liege lord. Likewise the Geatish woman lamented for Beowulf, with bound hair, sang a sorrowful song, said often that she greatly feared evil days for herself, many slaughters, fear of the foe, humiliation and captivity. Heaven swallowed the smoke. Beowulf 3143–3155 (Owen-Crocker 2000: 91, 93) INTRODUCTION Four dramatic funerals punctuate the tenth- or eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf; two involve the burning of the dead. While a Christian work to its core, the poem draws upon far older stories and at its very conclusion the poet provides a striking vision of an early medieval open-air cremation ceremony. Having died by the fire and poisonous bite of a dragon dwelling in a stone mound, the king of the Geats is cremated with treasures: helmets, swords, and coats of mail (Owen-Crocker 2000: 89). Before the raising of a burial mound upon a headland overlooking the sea, Beowulf ’s cremation is a focus of more than personal loss by mourners. -

Roseates Newsletter No 46

Quarterly NEWSLETTER Human Remains Repatriation from/to CHINA www.roseates.com No 46, Fourth Quarter 2019 Doctor takes patients' photos for the final journey THE ROSEATES End-of-life snapshots NEWSLETTER Your guide to human remains repatriation The Roseates Newsletter aims to update our clients and contacts on various topics related to the death of foreigners in China and Chinese abroad. The target audience includes consulates, foreign funeral directors and insurance companies. We welcome our readers to provide questions, comments and insights. CONTENTS Yao Shuai has taken about 10,000 photos from over 400 Introduction: The Roseates patients and their families Newsletter, your guide to One Chinese doctor is doing a bit more for his patients than human remains repatriation just prescribing painkillers or drugs. As the day shift at his Feature: End-of-life hospital ends at 6 pm, Yao Shuai goes to his office, which has snapshots been converted into a simple photo studio. He takes pictures Q&A: Answers to all your of patients set to embark on their final journey, often with questions family members close at hand. But before he takes the Policies: Protesters oppose photos, he asks a question that may seem at first insensitive building a new crematorium in but in actual fact is of immense benefit: “Are you afraid of Wenlou death?” Yao, a resident doctor in the department of cardiology Hongkongers to be allowed to at Tongzhou district hospital of traditional Chinese medicine in choose treatment they want Nantong, Jiangsu province, believes this direct approach is to receive if they become more humane and truthful. -

Frederick Monthly Meeting End of Life Planning Booklet

Planning Resources For End of Life Care Frederick Monthly Meeting Religious Society of Friends Frederick Monthly Meeting End of Life Planning Booklet Dear Frederick Friends, this is a revised version of Maury River Friends Meeting document entitled, “Planning Ahead: A Gift for my Family: Meeting the Responsibilities or Planning the End of Life.” It is revised to make the text relevant to Frederick Monthly Meeting (FMM) of the Religious Society of Friends as an opportunity to address these issues in a comprehensive and friendly way. Credit must be given to the thoughtful members of Maury River Meeting in Lexington, VA for their very hard and excellent work. I hope that Frederick Friends will consider this document for use in our Meeting. My thanks to all who have participated in this process, Virginia Spencer, Clerk, Ministry and Counsel Committee, 2008. It begins with: Elizabeth Grey Vining’s prayer on reaching her seventieth birthday O God our father, spirit of the universe, I am old in years and in the sight of others, but I do not feel old within myself. I have hopes and purposes, things I wish to do before I die. A surging of life within me cries, “Not yet! Not yet!” more strongly than it did ten years ago, perhaps because the nearer approach of death arouses the defensive strength of the instinct to cling to life. Help me to loosen, fiber and fiber, the instinctive strings that bind me to the life I know. Infuse me with thy spirit so that it is thee I turn to, not the old ropes of habit and thought. -

Grave Goods, Hoards and Deposits ‘In Between’I

Spectrums of depositional practice in later prehistoric Britain and beyond: grave goods, hoards and deposits ‘in between’i Anwen Cooper, Duncan Garrow and Catriona Gibson Paper accepted for publication in Archaeological Dialogues 27(2), Dec 2020 Abstract This paper critically evaluates how archaeologists define ‘grave goods’ in relation to the full spectrum of depositional contexts available to people in the past, including hoards, rivers and other ‘special’ deposits. Developing the argument that variations in artefact deposition over time and space can only be understood if different ‘types’ of finds location are considered together holistically, we contend that it is also vital to look at the points where traditionally defined contexts of deposition become blurred into one another. In this paper, we investigate one particular such category – body-less object deposits at funerary sites – in later prehistoric Britain. This category of evidence has never previously been analysed collectively, let alone over the extended time period considered here. On the basis of a substantial body of evidence collected as part of a nationwide survey, we demonstrate that body-less object deposits were a significant component of funerary sites during later prehistory. Consequently, we go on to question whether human remains were actually always a necessary element of funerary deposits for prehistoric people, suggesting that the absence of human bone could be a positive attribute rather than simply a negative outcome of taphonomic processes. We also argue that modern, fixed depositional categories sometimes serve to mask a full understanding of the complex realities of past practice and ask whether it might be productive in some instances to move beyond interpretatively confining terms such as ‘grave’, ‘hoard’ and ‘cenotaph’. -

Pricing Information October 2020

Woking Funeral Service Pricing Information October 2020 www.wokingfunerals.co.uk Funeral Prices Typically, funeral costs will include six elements: 1) Our professional service fees We will meet with you and your family to discuss the funeral arrangements, as well as providing guidance and advice on all the practical and legal documentation required like registering the death. We will organise the service, funeral and the wake. That includes the crematorium, cemetery or church, reception venues as appropriate, liaising with your chosen minister or celebrant and any additional products and services required. Our Funeral Director and branch team are available to provide help and guidance at all times. 2) Transfer & Care of the deceased When bringing your loved one into our care, we provide a professional, trained team with a private ambulance or other suitable vehicle. We will tend to the preparation and care of the deceased, including dressing in a suitable gown or their own clothes. You will also have use of our chapel of rest for visiting your loved one if you wish. 3) Ceremonial Vehicle(s) and Staff for the day of the Funeral Provision of a modern motor hearse to convey the deceased to the place of service and then to the crematorium or cemetery and a chauffeured limousine for 6 passengers (if applicable). Providing a Funeral Director and all the necessary staff, dressed in the appropriate livery, to conduct the funeral. (Alternative ceremonial vehicle types may be available at an additional cost). Funeral Package Options Horse-Drawn Eco-Coffin Personalised Solid Wood Traditional Westminster English Willow Reflections Surrey Worcester solid wood coffin eco-coffin personalised solid wood coffin wood-veneer coffin (oak or mahogany) (personalised options) picture coffin (oak or mahogany) (oak or mahogany) Professional £1,730 £1,730 £1,730 £1,730 £1,730 Services Transfer & Care £550 £550 £550 £550 £550 of the Deceased Ceremonial Vehicles £2,045 £995 £995 £995 £995 & Staff including incl. -

Cremation-2016.Pdf

Cremation Cremation is the act of reducing a corpse to ashes by burning, generally in a crematorium furnace or crematory fire. In funerals, cremation can be an alternative funeral rite to the burial of a body in a grave. Modern Cremation Process The cremation occurs in a 'crematorium' which consists of one or more cremator furnaces or cremation 'retorts' for the ashes. A cremator is an industrial furnace capable of generating 870-980 °C (1600-1800 °F) to ensure disintegration of the corpse. A crematorium may be part of chapel or a funeral home, or part of an independent facility or a service offered by a cemetery. Modern cremator fuels include natural gas and propane. However, coal or coke was used until the early 1960s. Modern cremators have adjustable control systems that monitor the furnace during cremation. A cremation furnace is not designed to cremate more than one body at a time, which is illegal in many countries including the USA. The chamber where the body is placed is called the retort. It is lined with refractory brick that retain heat. The bricks are typically replaced every five years due to heat stress. © 2016 All Star Training, Inc. Page 1 Modern cremators are computer-controlled to ensure legal and safe use, e.g. the door cannot be opened until the cremator has reached operating temperature. The coffin is inserted (charged) into the retort as quickly as possible to avoid heat loss through the top- opening door. The coffin may be on a charger (motorized trolley) that can quickly insert the coffin, or one that can tilt and tip the coffin into the cremator.