The Re-Framing of Historic Architecture and Urban Space in Contemporary Morocco (1990-Present)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Holy See

The Holy See APOSTOLIC JOURNEY OF HIS HOLINESS POPE FRANCIS TO MOROCCO 30-31 MARCH 2019 2 Live video transmission (Vatican Media) - Multimedia - Indications - Video message of His Holiness Pope Francis - Photo Gallery Saturday, 30 March 2019 ROME-RABAT Departure by air from Rome-Fiumicino Airport for Rabat 10.45 Greeting to journalists on the flight to Rabat 14.00 Arrival at Rabat-Salé International Airport Official Welcome 14:40 Welcome Ceremony on the Esplanade of the Hassan Tower Meeting with the Moroccan People, the Authorities, with Civil Society and with the 15:00 Diplomatic Corps on the Esplanade of the Hassan Tower 16:00 Visit to the Mausoleum of Mohammed V Courtesy Visit to King Mohammed VI in the Royal Palace Appeal by His Majesty King Mohammed VI and His Holiness Pope Francis regarding 16:25 Jerusalem / Al-Quds the Holy City and a place of encounter Visit to the Mohammed VI Institute for the Training of Imams, Morchidines and 17:10 Morchidates 18:10 Meeting with Migrants at the premises of diocesan Caritas of Rabat 3 Sunday, 31 March 2019 RABAT-ROME 9:30 Visit th the Centre Rural des Services Sociaux of Témara Meeting with Priests, Religious, Consecrated Persons and the Ecumenical Council of 10:35 Churches in the Cathedral of Rabat Angelus 12:00 Lunch with the Papal Entourage 14:45 Holy Mass - Prince Moulay Abdellah Stadium 17:00 Farewell Ceremony at Rabat-Salé International Airport Departure by air for Rome 17:15 Press Conference on the return flight from Rabat to Rome 21:30 Arrival at Rome-Ciampino International Airport Time zones Rome: + 1h UTC Rabat: + 1h UTC Bulletin of the Holy See Press Office, 9 February 2019 Bulletin of the Holy See Press Office, 26 February 2019 Bulletin of the Holy See Press Office, 25 March 2019 ©Copyright - Libreria Editrice Vaticana. -

Helena Chester the Discursive Construction of Freedom in The

The Discursive Construction of Freedom in the Watchtower Society Helena Chester Diploma of Teaching (Early Childhood): Riverina – Murray Institute of Higher Education Graduate Diploma of Education (Special Education): Victoria College. Master of Education (Honours): University of New England Thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Charles Darwin University, Darwin. October 2018 Certification I certify that the substance of this dissertation has not already been submitted for any degree and is not currently being submitted for any other degree or qualification. I certify that any help received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used, have been acknowledged in this thesis. Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 4 Dedication ............................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Abstract ..................................................................................................................... 6 Keywords .............................................................................................................................. 7 Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................................ 8 Chapter 1: The Discursive Construction of Freedom in the Watchtower Society ................... 9 The Freedom Claim in the Watchtower Society ............................................................. -

Marrakech Architecture Guide 2020

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Completed in 2008, the terminal extension of the Marrakech Menara Airport in Morocco—designed by Swiss Architects E2A Architecture— uses a gorgeous facade that has become a hallmark of the airport. Light filters into the space by arabesques made up of 24 rhombuses and three triangles. Clad in white aluminum panels and featuring Marrakesh Menara stylized Islamic ornamental designs, the structure gives the terminal Airport ***** Menara Airport E2A Architecture a brightness that changes according to the time of day. It’s also an ال دول ي ال م نارة excellent example of how a contemporary building can incorporate مراك ش مطار traditional cultural motifs. It features an exterior made of 24 concrete rhombuses with glass printed ancient Islamic ornamental motives. The roof is constructed by a steel structure that continues outward, forming a 24 m canopy providing shade. Inside, the rhombuses are covered in white aluminum. ***** Zone 1: Medina Open both to hotel guests and visitors, the Delano is the perfect place to get away from the hustle and bustle of the Medina, and escape to your very own oasis. With a rooftop restaurant serving ،Av. Echouhada et from lunch into the evening, it is the ideal spot to take in the ** The Pearl Marrakech Rue du Temple magnificent sights over the Red City and the Medina, as well as the شارع دو معبد imperial ramparts and Atlas mountains further afield. By night, the daybeds and circular pool provide the perfect setting to take in the multicolour hues of twilight, as dusk sets in. Facing the Atlas Mountains, this 5 star hotel is probably one of the top spots in the city that you shouldn’t miss. -

Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco

sustainability Article Tradition and Sustainability in Vernacular Architecture of Southeast Morocco Teresa Gil-Piqueras * and Pablo Rodríguez-Navarro Centro de Investigación en Arquitectura, Patrimonio y Gestión para el Desarrollo Sostenible–PEGASO, Universitat Politècnica de València, Cno. de Vera, s/n, 46022 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This article is presented after ten years of research on the earthen architecture of southeast- ern Morocco, more specifically that of the natural axis connecting the cities of Midelt and Er-Rachidia, located North and South of the Moroccan northern High Atlas. The typology studied is called ksar (ksour, pl.). Throughout various research projects, we have been able to explore this territory, documenting in field sheets the characteristics of a total of 30 ksour in the Outat valley, 20 in the mountain range and 53 in the Mdagra oasis. The objective of the present work is to analyze, through qualitative and quantitative data, the main characteristics of this vernacular architecture as a perfect example of an environmentally respectful habitat, obtaining concrete data on its traditional character and its sustainability. The methodology followed is based on case studies and, as a result, we have obtained a typological classification of the ksour of this region and their relationship with the territory, as well as the social, functional, defensive, productive, and building characteristics that define them. Knowing and puttin in value this vernacular heritage is the first step towards protecting it and to show our commitment to future generations. Keywords: ksar; vernacular architecture; rammed earth; Morocco; typologies; oasis; High Atlas; sustainable traditional architecture Citation: Gil-Piqueras, T.; Rodríguez-Navarro, P. -

FASTING and FEASTING in MOROCCO an Ethnographic Study of the Month of Ramadan

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/113158 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-06 and may be subject to change. FASTING AND FEASTING IN MOROCCO An ethnographic study of the month of Ramadan Marjo Buitelaar Fasting and Feasting in Morocco FASTING AND FEASTING IN MOROCCO An ethnographic study of the month of Ramadan. Een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Sociale Wetenschappen Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Katholiek Universiteit Nijmegen volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 28 mei 1991, des namiddags te I 30 uur precies door Maria Wilhelmina Buitelaar geboren op 4 oktober 1958 te Vlaardmgen Promotores: Prof. dr.AA Trouwborst Prof. dr. J.R.T.M. Peters Co-promotor: dr. H. G.G.M.Driessen Typography & Lay-out: André Jas, T.VA-producties Doetinchem Cover-illustration: painted detail of the minaret of the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakech. From: H. Terrasse & J. Hainaut Les Arts décoratifs au Maroc Casablanca: Afrique Orient 1988.Trouwborst For Leon Tíinyiar/ А Γ L A M ГІС OCH A M < Melilla СаааЫа El Jadi'Jä Map of Morocco TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowl edgements Note on the transcription Introduction 1 The argument Berkane and Marrakech Fieldwork Outline 1. Prescriptions on Fasting in Islamic law 11 The Koran on Fasting Fasting in the Hadith Interpretations by the Malikite School "The secrets of fasting" by al-Chazali 2. -

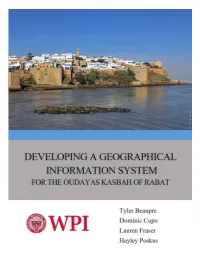

Developing a Geographical Information System for the Oudayas Kasbah of Rabat

Developing a Geographical Information System for the Oudayas Kasbah of Rabat An Interactive Qualifying Project (IQP) Proposal submitted to the faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelors of Science in cooperation with The Prefecture of Rabat Submitted by: Project Advisors: Tyler Beaupre Professor Ingrid Shockey Dominic Cupo Professor Gbetonmasse Somasse Lauren Fraser Hayley Poskus Submitted to: Mr. Hammadi Houra, Sponsor Liaison Submitted on October 12th, 2016 ABSTRACT An accurate map of a city is essential for supplementing tourist traffic and management by the local government. The city of Rabat was lacking such a map for the Kasbah of the Oudayas. With the assistance of the Prefecture of Rabat, we created a Geographical Information System (GIS) for that section of the medina using QGIS software. Within this GIS, we mapped the area, added historical landmarks and tourist attractions, and created a walking tour of the Oudayas Kasbah. This prototype remains expandable, allowing the prefecture to extend the system to all the city of Rabat. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction In 2012, the city of Rabat, Morocco was awarded the status of a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) world heritage site for integrating both Western Modernism and Arabo-Muslim history, creating a unique juxtaposition of cultures (UNESCO, 2016). The Kasbah of the Oudayas, a twelfth century fortress in the city, exemplifies this connection. A view of the Bab Oudaya is shown below in Figure 1. It is a popular tourist attraction and has assisted Rabat in bringing in an average of 500,000 tourists per year (World Bank, 2016). -

A Note from Sir Richard Branson

A NOTE FROM SIR RICHARD BRANSON “ In 1998, I went to Morocco with the goal of circumnavigating the globe in a hot air balloon. Whilst there, my parents found a beautiful Kasbah and dreamed of turning it into a wonderful Moroccan retreat. Sadly, I didn’t quite manage to realise my goal on that occasion, however I did purchase that magnificent Kasbah and now my parents’ dream has become a reality. I am pleased to welcome you to Kasbah Tamadot, (Tamadot meaning soft breeze in Berber), which is perhaps one of the most beautiful properties in the high Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I hope you enjoy this magical place; I’m sure you too will fall in love with it.” Sir Richard Branson 2- 5 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW 14 Babouches ACTIVITIES AT KASBAH Babysitting TAMADOT Cash and credit cards Stargazing Cigars Trekking in the Atlas Mountains Departure Asni Market Tours WELCOME TO KASBAH TAMADOT Do not disturb Cooking classes Fire evacuation routes Welcome to Kasbah Tamadot (pronounced: tam-a-dot)! Four legged friends We’re delighted you’ve come to stay with us. Games, DVDs and CDs This magical place is perfect for rest and relaxation; you can Kasbah Tamadot Gift Shop 1 5 do as much or as little as you like. Enjoy the fresh mountain air The Berber Boutique KASBAH KIDS as you wander around our beautiful gardens of specimen fruit Laundry and dry cleaning Activities for children trees and rambling rose bushes, or go on a trek through the Lost or found something? Medical assistance and pharmacy High Atlas Mountains...the choice is yours. -

QHN Spring 2020 Layout 1

WESTWARD HO! QHN FEATURES JOHN ABBOTT COLLEGE & MONTREAL’S WEST ISLAND $10 Quebec VOL 13, NO. 2 SPRING 2020 News “An Integral Part of the Community” John Abbot College celebrates seven decades Aviation, Arboretum, Islands and Canals Heritage Highlights along the West Island Shores Abbott’s Late Dean The Passing of a Memorable Mentor Quebec Editor’s desk 3 eritageNews H Vocation Spot Rod MacLeod EDITOR Who Are These Anglophones Anyway? 4 RODERICK MACLEOD An Address to the 10th Annual Arts, Matthew Farfan PRODUCTION Culture and Heritage Working Group DAN PINESE; MATTHEW FARFAN The West Island 5 PUBLISHER A Brief History Jim Hamilton QUEBEC ANGLOPHONE HERITAGE NETWORK John Abbott College 8 3355 COLLEGE 50 Years of Success Heather Darch SHERBROOKE, QUEBEC J1M 0B8 The Man from Argenteuil 11 PHONE The Life and Times of Sir John Abbott Jim Hamilton 1-877-964-0409 (819) 564-9595 A Symbol of Peace in 13 FAX (819) 564-6872 St. Anne de Bellevue Heather Darch CORRESPONDENCE [email protected] A Backyard Treasure 15 on the West Island Heather Darch WEBSITES QAHN.ORG QUEBECHERITAGEWEB.COM Boisbriand’s Legacy 16 100OBJECTS.QAHN.ORG A Brief History of Senneville Jim Hamilton PRESIDENT Angus Estate Heritage At Risk 17 GRANT MYERS Matthew Farfan EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MATTHEW FARFAN Taking Flight on the West Island 18 PROJECT DIRECTORS Heather Darch DWANE WILKIN HEATHER DARCH Muskrats and Ruins on Dowker Island 20 CHRISTINA ADAMKO Heather Darch GLENN PATTERSON BOOKKEEPER Over the River and through the Woods 21 MARION GREENLAY to the Morgan Arboretum We Go! Heather Darch Quebec Heritage News is published quarterly by QAHN with the support Tiny Island’s Big History 22 of the Department of Canadian Heritage. -

1 the Moroccan Colonial Archive and the Hidden History of Moroccan

1 The Moroccan Colonial Archive and the Hidden History of Moroccan Resistance Maghreb Review, 40:1 (2014), 108-121. By Edmund Burke III Although the period 1900-1912 was replete with numerous important social upheavals and insurrections, many of which directly threatened the French position in Morocco, none of them generated a contemporaneous French effort to discover what went wrong. Instead, the movements were coded as manifestations of supposedly traditional Moroccan anarchy and xenophobia and as such, devoid of political meaning. On the face of it, this finding is surprising. How could a French policy that billed itself as “scientific imperialism” fail to consider the socio-genesis of Moroccan protest and resistance? Despite its impressive achievements, the Moroccan colonial archive remains haunted by the inability of researchers to pierce the cloud of orientalist stereotypes that occluded their vision of Moroccan society as it actually was. For most historians, the period of Moroccan history between 1900 and 1912 is primarily known as “the Moroccan Question.” A Morocco-centered history of the Moroccan Question was impossible for Europeans to imagine. Moroccan history was of interest only insofar as it shed light on the diplomatic origins of World War I. European diplomats were the main actors in this drama, while Moroccans were pushed to the sidelines or reduced to vulgar stereotypes: the foolish and spendthrift sultan Abd al-Aziz and his fanatic and anarchic people. Such an approach has a degree of plausibility, since the “Moroccan Question” chronology does provide a convenient way of structuring events: the Anglo-French Accord (1904), the landing of the Kaiser at Tangier (1905), the Algeciras conference (1906), the landing of French troops at Casablanca (1907), the Agadir incident (1911) and the signing of the protectorate treaty (1912). -

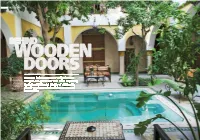

Morocco Hides Its Secrets Well; Who Can Riad in Marrakesh, Morocco

INTERIORS TexT KALPANA SUNDER A patio with a pool at the centre of a Morocco hides its secrets well; who can riad in Marrakesh, Morocco. A riad imagine the splendour of a riad? Slip away is known for the lush greenery that from the hustle and bustle of aggressive is intrinsic to its open-air courtyard, street vendors and step into a cocoon of making it an oasis of peace. tranquillity. Frank Waldecker/Look/Dinodia Frank 74•JetWings•December 2014 JetWings•December 2014•75 Interiors AM IN THE lovely rose-pink Moroccan Above: View from the of terracotta roofs and legions of satellite dishes. town of Marrakesh, on the fringes of the rooftop of a riad that The minaret of the Koutoubia Mosque, the tallest lets you see all the Sahara, and in true Moroccan spirit, I’m way to the medina building in the city, is silhouetted against a crimson staying at a riad. Riads are traditional (the old walled part) sky; in the distance, the evocative sound of the Moroccan homes with a central courtyard of Marrakesh. muezzin called the faithful to prayer. With arched garden; in fact, the word riad is derived Below: A traditional cloisters, pots of lush tangerine bougainvillea and fountain in the inner from the Arabic word for garden. They offer courtyard of a riad in tiled courtyards, this is indeed a visual feast. refuge from the clamour and sensory overload of Fez, Morocco’s third the streets, as well as protection from the intense largest city, brings WHAT LIES WITHIN a sense of coolness cold of the winter and fiery warmth of the summer. -

Cultural Morocco FAM

Cultural Morocco FAM CULTURAL MOROCCO Phone: +1-800-315-0755 | E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cultureholidays.com CULTURE HOLIDAYS Cultural Morocco FAM Tour Description Morocco is a gateway to Africa and a country of dizzying diversity. Here you'll find epic mountain ranges, ancient cities, sweeping deserts – and warm hospitality. Morocco is quickly becoming one of the world’s most sought-after tourist destinations. From Casablanca through Rabat and Tangier at the tip of the continent; from the infinite blue labyrinth streets of Chefchaouen, and down to Fez, and still further south to the ever-spreading dunes of Erg Chebbi in the Sahara Desert; over to Marrakech, and the laid-back coastal town of Essaouira, Morocco has an abundance of important natural and historical assets. Marrakech Known as the capital of Morocco under the reign of Youssef Ben Tachfine, this “Pearl of the South” known as Marrakesh, remains one of the top attractions of tourists . Fez in the north of Morocco is a crucial center of commerce and industry (textile mills, refineries, tanneries and soap), thus making crafts and textiles an important part of the city’s past and present economy. The city, whose old quarters are classified world heritage by UNESCO, is a religious and intellectual center as well as an architectural gem. Rabat is the capital of Morocco and is a symbol of continuity in Morocco. At the heart of the city, stands the Hassan Tower, the last vestige of an unfinished mosque. Casablanca Known as the international metropolis whose development is inseparable from the port activity, Casablanca is a major international business hub. -

The Grand Tour

MOROCCO THE GRAND TOUR APRIL 3-21, 2019 TOUR LEADER: SUE ROLLIN MOROCCO Overview THE GRAND TOUR Discover the best of Morocco on this 19-day tour, from its rich and diverse Tour dates: April 3-21, 2019 architectural heritage to its vibrant cultural traditions, stunning landscapes and unique gastronomy. Tour leader: Sue Rollin From Roman times we see the splendid ruins of Volubilis and the port of Lixus on the Atlantic coast, once famous for its salt and fish paste. After Tour Price: $9,820 per person, twin share the Romans came the Vandals and the Byzantines who ruled the region Single Supplement: $2,295 for sole use of until the Arab conquest brought Islam in the eighth century. The local double room Berber tribes converted to the new religion and a blend of Berber and Arab culture produced the characteristic art and architecture of Islamic Booking deposit: $500 per person Morocco, with its intricate stucco and wood carving and colourful zellij mosaic tilework. Recommended airline: Emirates We visit the old medina of Rabat and drive along the coast to Tangier, Maximum places: 20 overlooking the straits of Gibraltar, before going into the Rif Mountains and the charming medieval town of Chefchaouen. We explore Fes, renowned Itinerary: Rabat (2 nights), Tangier (2 nights), for its warren of market streets and exquisitely decorated medersas and Chefchaouen (1 night), Fes (3 nights), Ifrane (1 enjoy the scenery of the Middle Atlas, home to forests of Atlas cedar and night), Marrakesh (3 nights), Ouarzazate (2 Barbary apes. Marrakesh is famous for its palaces, gardens and fine nights), Taroudant (1 night), Essaouira (2 mausolea and there is plenty of time to lose ourselves in the labyrinthine nights), Casablanca (1 night) souks which run off the Jemaa el Fna, the city’s bustling main square.