Time Measurement in Tibet: a Critical Introduction to the Works on Kālacakra Astronomy by Dieter Schuh, *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER of the Dowsing Society of Victoria Inc

NEWSLETTER of the Dowsing Society of Victoria Inc. No. 54 April 2009 PO Box 2635, Mount Waverley, Victoria, 3149 Web address: www.dsv.org.au Registration: A0035189A DSV philosophy: Through awakening consciousness, we are empowered with knowledge and skills to unconditionally serve others. NEXT MEETING I believe compassion and strengthened Sunday, 26th April, 2009 community ties are two things we can look forward to with the new emerging energies. PRESIDENT’S REPORT Please continue to send healing to the Earth as a whole. We have relied on her for so much, After a very hot, dry summer and a truly without considering the consequences. I’m sure horrible February, the arrival of autumn is very that transmuting negative energies, using welcome. Some have attributed the bushfires, environmentally-friendly products, recycling, and the strong winds and earth tremors in Victoria - projecting positive thoughts all help. plus the floods and hurricane in Queensland - to the Earth’s cleansing. I’m pleased to report that our visit to Hanging Rock was successful, with 30 people attending One positive outcome from the fires has been on 29th March – the most we’ve ever had for a the compassion extended. In spite of all the DSV field trip. It was a good dowsing experience. people and animals that perished and the hundreds who lost homes and businesses, a For our next meeting, our AGM, Dennis Toop strong sense of community has developed. from South Australia will speak to us about his experiences with property dowsing and There’s also been overwhelming generosity transmuting negative energies. -

The Art of Non-Violence Winning China Over to Tibet’S Story

The Art of Non-violence Winning China Over to Tibet’s Story Thubten Samphel The Tibet Policy Institute 2017 The Art of Non-violence Winning China Over to Tibet’s Story Thubten Samphel The Tibet Policy Institute 2017 Published by: Tibetan Policy Centre CTA, Gangchen Kyishong, Dharamshala -176215 Distt. Kangra HP INDIA First Edition : 2107 No. of Copies : 200 Printed at Narthang Press, Central Tibetan Administration Gangchen Kyishong, Dharamshala, HP, INDIA Foreword I am happy that the Tibet Policy Institute has come out with The Art of Non-violence: Winning China Over to Tibet’s Story. The Tibetan outreach to our Chinese brothers and sisters is an important effort on the part of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the Central Ti- betan Administration (CTA) to persuade the Chinese public that the Tibetan people’s non-violent struggle is neither anti-China nor anti-Chinese people. This protracted struggle is waged against the wrong policies the Chinese Communist Party implements in Tibet. As a part of this effort to explain the nature of the Tibetan people’s struggle to the broader Chinese masses, CTA instituted many years ago a China Desk at the Department of Information and Interna- tional Relations (DIIR). The China Desk maintains a web site in the Chinese language, www.xizang-zhiye.org, to educate the Chinese public on the deteriorating conditions in Tibet, the just aspirations of the Tibetan people and a reasonable solution to the vexed issue of Tibet. The solution to this protracted issue is the Middle Way Approach which does not seek independence for Tibet but for all the Tibetan people to enjoy genuine autonomy as enshrined in the constitution of the People’s Republic of China. -

CALENDRICAL CALCULATIONS the Ultimate Edition an Invaluable

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05762-3 — Calendrical Calculations 4th Edition Frontmatter More Information CALENDRICAL CALCULATIONS The Ultimate Edition An invaluable resource for working programmers, as well as a fount of useful algorithmic tools for computer scientists, astronomers, and other calendar enthu- siasts, the Ultimate Edition updates and expands the previous edition to achieve more accurate results and present new calendar variants. The book now includes algorithmic descriptions of nearly forty calendars: the Gregorian, ISO, Icelandic, Egyptian, Armenian, Julian, Coptic, Ethiopic, Akan, Islamic (arithmetic and astro- nomical forms), Saudi Arabian, Persian (arithmetic and astronomical), Bahá’í (arithmetic and astronomical), French Revolutionary (arithmetic and astronomical), Babylonian, Hebrew (arithmetic and astronomical), Samaritan, Mayan (long count, haab, and tzolkin), Aztec (xihuitl and tonalpohualli), Balinese Pawukon, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Hindu (old arithmetic and medieval astronomical, both solar and lunisolar), and Tibetan Phug-lugs. It also includes information on major holidays and on different methods of keeping time. The necessary astronom- ical functions have been rewritten to produce more accurate results and to include calculations of moonrise and moonset. The authors frame the calendars of the world in a completely algorithmic form, allowing easy conversion among these calendars and the determination of secular and religious holidays. Lisp code for all the algorithms is available in machine- readable form. Edward M. Reingold is Professor of Computer Science at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Nachum Dershowitz is Professor of Computational Logic and Chair of Computer Science at Tel Aviv University. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05762-3 — Calendrical Calculations 4th Edition Frontmatter More Information About the Authors Edward M. -

A Short Biography of Four Tibetan Lamas and Their Activities in Sikkim

BULLETIN OF TIBETOLOGY 49 A SHORT BIOGRAPHY OF FOUR TIBETAN LAMAS AND THEIR ACTIVITIES IN SIKKIM TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA Namgyal Institute of Tibetology Summarised English translation by Saul Mullard and Tsewang Paljor Translators’ note It is hoped that this summarised translation of Lama Tsultsem’s biography will shed some light on the lives and activities of some of the Tibetan lamas who resided or continue to reside in Sikkim. This summary is not a direct translation of the original but rather an interpretation aimed at providing the student, who cannot read Tibetan, with an insight into the lives of a few inspirational lamas who dedicated themselves to various activities of the Dharma both in Sikkim and around the world. For the benefit of the reader, we have been compelled to present this work in a clear and straightforward manner; thus we have excluded many literary techniques and expressions which are commonly found in Tibetan but do not translate easily into the English language. We apologize for this and hope the reader will understand that this is not an ‘academic’ translation, but rather a ‘representation’ of the Tibetan original which is to be published at a later date. It should be noted that some of the footnotes in this piece have been added by the translators in order to clarify certain issues and aspects of the text and are not always a rendition of the footnotes in the original text 1. As this English summary will be mainly read by those who are unfamiliar with the Tibetan language, we have refrained from using transliteration systems (Wylie) for the spelling of personal names, except in translated footnotes that refer to recent works in Tibetan and in the bibliography. -

Shambhala Office of Practice and Education

Shambhala Office of Practice and Education TO: All Shambhala International Calendar Planners RE: Earth Mouse Year (2008-2009) and Earth Ox Year (2009-2010) Calendars DATE: 4 January 2007 This year the Shambhala Office of Practice and Education is assuming responsibility for providing you with all the necessary information from the Tibetan calendar for the coming year – in this case the years of the Earth Mouse and the Earth Ox. We are utilizing the work of Edward Henning from the U.K. On his website at www.kalacakra.org you will find a large archive of complete Tibetan calendars for the years 1450-2049. The standard Tibetan calendar that our community has always followed is known as that of the Phukpa tradition, and this particular archive is to be found at www.kalacakra.org/calendar/tiblist.htm. We believe that you will find it easy to compile all the necessary dates directly from this website, and thus your ability to plan many years into the future will now be possible. Below are all the specific dates for feasts, Jambhala, Sadhana of Mahamudra, and Werma Sadhana practice. In accordance with the Tibetan lunar calendar, we practice the feast for Padmakara, Chakrasamvaya on the 10th day and Vajrayogini on the 25th day; Jambhala sadhana is practiced on the 8th and 28th days; Sadhana of Mahamudra is practiced on the full (15th) and new (30th) moon days; and the Werma Sadhana is practiced on the protector days (9th, 19th, 29th). Milarepa Day is the 14th day of the 1st month. Centres may schedule this celebration on the nearest weekend. -

Pacifying the Date of Cutting Hair

From the Sutra Chapter of Bodhisattva’s Hair Pacifying the Date of Cutting Hair Lama Zopa Rinpoche recently translated this text giving the results of cutting one’s hair on various days (and it applies to ordained people and lay people alike). The days mentioned come from the Tibetan calendar; therefore, check a Tibetan calendar such as the Liberation Prison Project calendar to find the best date to cut your hair. 1st of the month – one will 13th– it is good for all living have a short life beings 2nd of the month – one will 14th– one will become wealthy have many diseases 15th– it is auspicious 3rd – wealth will come 16th– one will have thirst 4th– one will have good 17th– the color of your flesh 27th– one’s virtue will increase complexion of one’s body will turn blue 28th– fighting and quarrelling 5th– one’s possessions will 18th– one will receive will happen increase possessions 29th– one’s life/spirit 6th– one will be sued (court 19th– one will meet good potential will wander case) people (people who will help 30th– one will meet with 7th– one’s complexion will you) persons who have died and disappear (body color will 20th– one will have hunger have been reborn as spirits in disappear) and thirst human form. 8th– one will have long life 21st– one will have diseases 9th– one will meet youthful 22nd–one will find food and Colophon: people (boyfriend, girlfriend) water Translated by Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Crestone Colorado, June 2008. Scribed by Ven. Holly 10th– one will have great 23rd–good will come, things Ansett. -

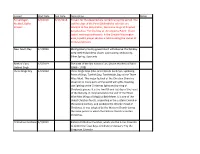

Subject Start Date End Date Description Notes Farvardegan, 8/8/2018 8/17/2018 Prayers for the Departed Are Recited During the Period

Subject Start Date End Date Description Notes Farvardegan, 8/8/2018 8/17/2018 Prayers for the departed are recited during the period. The Muktad, Gatha last five days of the Parsi (Shahnshahi) calendar are Prayers devoted to five Holy Gathas, the divine songs of Prophet Zarathushtra. The final day of the period is Pateti - (from ‘patet’ meaning confession). In the Greater Washington area, a public prayer service is held invoking the names of deceased persons. New Year's Day 1/1/2019 Montgomery County government will observe this holiday. Area: Bethesda/Chevy Chase, East County, MidCounty, Silver Spring, Upcounty Birth of Guru 1/5/2019 The birth of the last human Guru (divine teacher) of Sikhs Gobind Singh (1666 - 1708) Three Kings Day 1/6/2019 Three Kings Days (also called Dia de los Reyes, Epiphany, Feast of Kings, Twelfth Day, Twelfthtide, Day of the Three Wise Men). This major festival of the Christian Church is observed in many parts of the world with gifts, feasting, last lighting of the Christmas lights and burning of Christmas greens. It is the Twelfth and last day of the Feast of the Nativity. It commemorates the visit of the Three Wise Men (Kings of Magi) to Bethlehem. It is one of the oldest Christian feasts, originating in the Eastern Church in the second century, and predates the Western feast of Christmas. It was adopted by the Western Church during the same period in which the Eastern Church accepted Christmas. Orthodox Christmas 1/7/2019 Eastern Orthodox Churches, which use the Julian Calendar to determine feast days, celebrate on January 7 by the Gregorian Calendar. -

The Bahá'í Calendar

16 The Bahá’í Calendar In the not far distant future it will be necessary that all peoples in the world agree on a common calendar. It seems, therefore, fitting that the new age of unity should have a new calendar free from the objections and associations which make each of the older calendars unacceptable to large sections of the world’s population, and it is difficult to see how any other arrangement could exceed in simplicity and convenience that proposed by the Báb. John Ebenezer Esslemont: Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era: An Introduction to the Bahá’í Faith (1923)1 16.1 Structure The Bahá’í (or Bad¯ı‘) calendar begins its years on the day of the vernal equinox. If the actual time of the equinox in Tehran occurs after sunset, then the year begins a day later [3]. This astronomical version of the Bahá’í calendar [4] is described in Section 16.3. Until recently, practice in the West had been to begin years on March 21 of the Gregorian calendar, regardless. This arithmetical version is described in Section 16.2. The calendar, based on cycles of 19, was established by the Bab¯ (1819−1850), the martyred forerunner of Baha’u’ll¯ ah,¯ founder of the Bahá’í faith. As in the Hebrew and Islamic calendars, days are from sunset to sunset. Unlike those calendars, years are solar; they are composed of 19 months of 19 days each with an additional period of 4 or 5 days after the eighteenth month. Until recently, leap years in the Western version of the calendar followed the same pattern as in the Gregorian calendar. -

Buddhist Pilgrimage and the Ritual Ecology of Sacred Sites in the Indo-Gangetic Region

religions Article Buddhist Pilgrimage and the Ritual Ecology of Sacred Sites in the Indo-Gangetic Region David Geary 1 and Kiran Shinde 2,* 1 Department of Community, Culture and Global Studies, University of British Columbia, Kelowna, BC V1V 1V7, Canada; [email protected] 2 Department of Social Enquiry, School of Humanities, La Trobe University, Melbourne 3083, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In contemporary India and Nepal, Buddhist pilgrimage spaces constitute a ritual ecology. Not only is pilgrimage a form of ritual practice that is central to placemaking and the construction of a Buddhist sacred geography, but the actions of religious adherents at sacred centers also involve a rich and diverse set of ritual observances and performances. Drawing on ethnographic research, this paper examines how the material and corporeal aspects of Buddhist ritual contribute to the distinctive religious sense of place that reinforce the memory of the Buddha’s life and the historical ties to the Indian subcontinent. It is found that at most Buddhist sites, pilgrim groups mostly travel with their own monks, nuns, and guides from their respective countries who facilitate devotion and reside in the monasteries and guest houses affiliated with their national community. Despite the differences across national, cultural–linguistic, and sectarian lines, the ritual practices associated with pilgrimage speak to certain patterns of religious motivation and behavior that contribute to a sense of shared identity that plays an important role in how Buddhists imagine themselves as part of a translocal religion in a globalizing age. Citation: Geary, David, and Kiran Keywords: Buddhist pilgrimage; ritual ecology; Buddhism; Bodhgaya; Buddhist heritage Shinde. -

Tibetan Calendar 2019-2020 ས་ཕག་ལོའི་༢༡༤༦།

Tibetan Calendar 2019-2020 ས་ཕག་ལོའི་༢༡༤༦། Year of Earth Pig, Losar 2146 It is an animal who by nature is calmed and relaxed. He is happier when he is at home surrounded by his family. It is a person who organizes, plans and always has a plan to complete any tasks. He loves peace and tries to keep it where he goes. Références: Ea- W. Earth - Wind: The meeting of the earth and the wind is an unfavourable combination, because of this unfavourable combination one's food and materials will run out. Sorrows such as being robbed and so forth will occur and one will not accomplish one's own aims. Ea-F, Earth - Fire: The meeting of earth and fire is a combination which burns, this combination of burning will generate suffering. People will go to war, destroy enemies, do violent actions, have disputes and it will bring all sorts of sufferings to the opponents. Ea-Wa, Earth - Water: The meeting of earth and water connects us to health. this connection makes one become very happy. It is positive for hosting a party, promoting ourselves to a better position, dressing up, putting on ornaments and enjoying sports. Ea-Ea, Earth - Earth: When two earths meet, it will bring real accomplishment. When there is a real attainment, all one has in mind will be accomplished. When this combination is the case, making statues, construction plans, buying land, increasing actions, actions of stability such as having a spouse and so forth will be positive. F-Wa, Fire - Water: The meeting of fire and water is a combination for death, the combination of death takes away one's own life-force. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 40 3rd International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2016) A Brief Discussion on Formation of Zangmi Tancheng Art Jianxun Yuan Hezuo National Normal Advanced School Hezuo, Gansu, China 747000 Abstract—In this paper, the author analyzed the formation of However, the introduction of Tantrism to Tibet had Tantric history of Tibetan Buddhism and other cultural elements encountered a problem of the relation with BonPo culture in Zangmitancheng art. It points out that Zangmitancheng art is which had a long history at the beginning. Tantrism chose to one kind of brand-new art which it on basis of Yinmitancheng attach itself to BonPo with a tolerant attitude, and reached it and it incorporating BonPo culture and Han culture. tentacles into the hearts of believers to strive for understanding and sympathy. For example, when constructing Jokhang Keywords—Zangmi; Tancheng; BonPo; art Temple, 卍 (Gyung Drung) was painted on the four doors of the temple to entertain BonPo believers, and check (one of I. INTRODUCTION BonPo patterns) was painted to entertain civilians." But such In Zangmi art, Tancheng is regarded as the most sacred, tolerance and attachment destined the weak personality of mysterious and characteristic representative of religious art, for Buddhism and the inheritance of BonPo spirit from the the practicing monks, it is the communication to "visualize" beginning [2]. the gods, and practitioners can reach the Spiritual World and Up to the 8th century, after a fight between Buddhism and communicate with gods through Tancheng. For the general BonPo which presented as religious dispute but was political believers, it is a sacred object to worship the god and Buddha. -

The Mirror 44 April-May 1998

THE MIRROR Newspaper of the International Dzogchen Community April/May 1998-Issue No. 44 A.S.I.A. Projects in Tibet by Giorgio Minuzzo Reclining Buddha at Wat Po Thailand Teachings of Chögyal Namkhai Norbu by Martin Perenchio .A-t 5:30 AM on February 3rd, embodied in their years of practice. three of Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche's About forty people attended the students met him and his wife Rosa three sessions, and as usual, they Tibetan children at the Bangkok airport after the two were an internationally diverse lot. had just flown in from Australia. The following day, February Two days later, Rinpoche and Rosa 15th, Rinpoche, Rosa, Fabio, and were relaxing in a beachside resort three local students flew to Burma T The village of Dzam Thog situated in East Tibet, is on Koh Samet, an island off the for a brief tour of the Burmese mon A he A.S.I.A. project called 'Program for the Develop more than a thousand kilometers south of Damche southeast coast of Thailand. There uments in Rangoon, Mandalay. and ment of the Health and Educational Conditions of the (three or four days of travel). Dzam Thog village, which they were joined by a small circle of the multifaceted architectural jew Village of Dzam Thog' is a project jointly financed with lends its name to the project, is situated on the right bank followers and well-wishers for days els of Pagan. The following week, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MAE) which of the Yantze River (Blue River) which is called Dri Chu of swimming, sunbathing, and Rinpoche and his party flew to Sin started in the spring of 1996.