Elena A. Melʹnikova. Futhark 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viking-Age Runic Plates of the Runic Plates Have Been Conducted with a Stereomicroscope for This Purpose

The aim of this dissertation is to represent as clearly as possible the genre of Viking- Age runic plates by developing readings and interpretations of the inscriptions on the 46 metal plates with runes from the Viking Age known today. Several investigations SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH • • PERESWETOFF-MORATH SOFIA Viking-Age Runic Plates of the runic plates have been conducted with a stereomicroscope for this purpose. On the basis of the new readings thus established, new interpretations have been pro- posed for the most problematic sections of previously interpreted inscriptions. New interpretations are also offered for inscriptions on runic plates which have previously been considered non-lexical. As well as providing new readings and interpretations, this study has resulted in clarification of the relationship between the form and content of the inscriptions on the runic plates on the one hand and on their find circumstances and appearance on the other. An argued documentation of the readings can be found in an accompanying catalogue in Swedish which is published digitally and can be downloaded as a pdf file at: <http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-383584> Viking-Age Runic Plates Viking-Age Distribution: Sofia Pereswetoff-Morath eddy.se ab e-post: [email protected] ISSN 0065-0897 and Box 1310, 621 24 Visby. Telefon: 0498-25 39 00 ISSN 1100-1690 http://kgaa.bokorder.se ISBN 978-91-87403-33-0 1 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI 155 Runrön 21 Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 2 3 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI CLV Runrön 21 Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH Viking-Age Runic Plates Readings and Interpretations Translated from Swedish by Mindy MacLeod UPPSALA 2019 Kungl. -

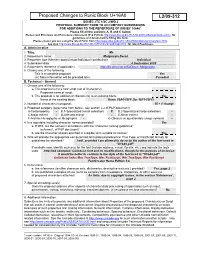

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4. -

THE NINE DOORS of MIDGARD a Curriculum of Rune-Work

,. , - " , , • • • • THE NINE DOORS OF MmGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work - • '. Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin·Drighten of the Rune-Gild THE NINE DOORS OF MIDGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin-Drighten of the Rune-Gild 1997 - Introduction This work is the first systematic introduction to Runelore available in many centuries. This age requires and allows some new approaches to be sure. We have changed over the centuries in question. But at the same time we are as traditional as possible. The Gild does not fear innovation - in fact we embrace it - but only after the tradition has been thoroughly examined for all it has to offer. Too often in the history of the runic revival various proponents have actually taken their preconceived notions about what the Runes should say- and then "runicized" them. We avoid this type of pseudo-innovation at all costs. Our over-all magical method is a simple one. The tradition posits an outer world (objective reality) and an inner-world (subjective reality). The work of the Runer is the exploration of both of these worlds for what they have to offer in the search for wisdom. In learning the Runes, the Runer synthesizes all the objective lore and tradition he can find on the Runes with his subjective experience. In this way he "makes the Runes his own." All the Runes and their overall system are then used as a sort of "meta-Ianguage" in meaningful communication between these objective and subjective realities. The Runer may wish to be active in this communication - to cause changes to occur in accordance with his will, or he may wish to learn from one of these realities some information which would normally be hidden from him. -

Elder Futhark Rune Poem and Some Notes RYKHART: ODINSXRAL

Elder Futhark Rune Poem and some notes RYKHART: ODINSXRAL Dedication Mysteries ancient, Allfather found Wrested from anguish, nine days fast bound Hung from the world tree, pierced by the spear Odin who seized them, make these staves clear 1 Unless otherwise specified, all text and artwork within ELDER FUTHARK RUNE POEM and some notes RYKHART: ODINSXRAL are copyright by the author and is not to be copied or reproduced in any medium or form without the express written permission of the author Reikhart Odinsthrall both Reikhart Odinsthrall and RYKHART: ODINSXRAL are also both copyright Dec 31, 2013 Elder Futhark Rune Poem by Reikhart Odinsthrall is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Based on a work at http://odinsthrall.co.uk/rune-poem.html. 2 F: Fehu : Cattle / Wealth Wealth is won and gold bestowed But honour's due to all men owed Gift the given and ware the lord For thy name's worth noised abroad U: Uruz : Aurochs / Wild-ox Wild ox-blood proud, sharp hornéd might On moorland harsh midst sprite and wight Unconquered will and fierce in form Through summer's sun and winter's storm X: Thurisaz : Thorn / Giant / Thor Thorn hedge bound the foe repelled A giant's anger by Mjolnir felled Thor protect us, fight for troth In anger true as Odin's wrath A: Ansuz : As / God / Odin In mead divine and written word In raven's call and whisper heard Wisdom seek and wise-way act In Mimir's well see Odin's pact R: Raidho : Journey / Carriage By horse and wheel to travel far Till journey's -

Pursuing West: the Viking Expeditions of North America

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2015 Pursuing West: The iV king Expeditions of North America Jody M. Bryant East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Jody M., "Pursuing West: The iV king Expeditions of North America" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2508. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2508 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pursuing West: The Viking Expeditions of North America _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _____________________ by Jody Melinda Bryant May 2015 _____________________ Dr. William Douglas Burgess, Jr., Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. John M. Rankin Keywords: Kensington Rune Stone, Runes, Vikings, Gotland ABSTRACT Pursuing West: The Viking Expeditions of North America by Jody Bryant The purpose to this thesis is to demonstrate the activity of the Viking presence, in North America. The research focuses on the use of stones, carved with runic inscriptions that have been discovered in Okla- homa, Maine, Rhode Island and Minnesota. The thesis discusses orthographic traits found in the in- scriptions and gives evidence that links their primary use to fourteenth century Gotland. -

Proposed Additions to the Runic Range, L2/09-312 2

Proposed additions to the Runic Range 16A0-16F0 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS 1 FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 10646TP PT Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from HTUhttp://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html UTH for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from HTUhttp://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.htmlUTH. See also HTUhttp://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html UTH for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Proposed additions to the Runic Range, L2/09-312 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: Oct. 29, 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): prof. dr hab. Jacek Fisiak, prof. dr hab. Marcin Krygier 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic Range 16A0-16F0 [Combining Diacritical Marks Supplement 1DC0-1DFF] 2. Number of characters in proposal: variable: 7 + (1) + 16/[12 + 1] see: 2. Justification (ii) & 4. Description 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary B.1-Specialized (small collection) B.2-Specialized (large collection) C-Major extinct X D-Attested extinct E-Minor extinct F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols 4. -

Two Personal Names in Recently Found Anglo-Saxon Runic Inscriptions: Sedgeford (Norfolk) and Elsted (West Sussex)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Online Research @ Cardiff Aufsatz Prof. John Hines Anglia 137/2 (2019) E-Mail: [email protected] Red. München John Hines* Two Personal Names in Recently Found Anglo-Saxon Runic Inscriptions: Sedgeford (Norfolk) and Elsted (West Sussex) Abstract: In 2017 two objects carrying runic inscriptions that are identifiable as personal names were found. Both date to the ninth century; both are dithematic (compound) names. The object, identified as a spoon or fork handle from Sedgeford in Norfolk, bears a familiar male name, Biarnferð. This contains a runic graph hitherto unseen, which may, despite the provenance of the find, be interpreted as a representation of the diphthong ia that developed in the Kentish dialect by the middle of the ninth century. There is in fact a historically known individual of this name who witnessed a series of Canterbury charters in the mid-ninth century. The other object, a strap-end from Elsted in West Sussex, carries what can be identified from its final element, -flǣd, as a female name, although the whole name cannot be read. What is legible cannot be identified with any previously recorded personal name. Evaluation of these finds emphasizes how Anglo-Saxon runic writing practice continued to adapt to changes in the language and the regularization of roman-script literacy in the ninth century. Finally, the role of literacy within a nexus of cultural relationship involving individuals and artefacts is also highlighted. *Corresponding author: John Hines, Cardiff University E-Mail: [email protected] 1 Two New Runic Finds Early in 2017, two objects came to light which are inscribed with short sequences of Anglo- Saxon runes that can be identified as individual personal names. -

Documentation of Runic Inscriptions

Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 24 Knirk, James E., 2021: Documentation of Runic Inscriptions. In: Reading Runes. Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium on Runes and Runic Inscriptions, Nyköping, Sweden, 2–6 September 2014. Ed. by MacLeod, Mindy, Marco Bianchi and Henrik Williams. Uppsala. (Runrön 24.) Pp. 15–42. DOI: 10.33063/diva-438865 © 2021 James E. Knirk (CC BY) Plenary lecture JAMES E. KNIRK Documentation of Runic Inscriptions Abstract Documentation and examination are the essence of runological fieldwork. As discussed here, the recording aspect concerns the inscriptions, particularly the runes, themselves. The documenta- tion of runic carvings is a multifaceted activity. It ranges from the production of reading proto- cols during the examination of inscriptions to the utilization of various techniques for registering what is found on the runic object: (a) visually, i.e. with drawings or photographs, (b) physically, e.g. with squeezes or casts, and (c) scientifically, such as by employment of microscopes, 3D scan- ning, or most recently Reflectance Transformation Imaging. The main requirement for all such documentation is objectivity. Keywords: Documentation, runic inscriptions, reading protocols, drawings, photography, squeezes, casts, stereo microscope, 3D scanning, Reflectance Transformation Imaging Introduction Discovery, documentation, and decipherment are the three broad aspects of the theme “Reading Runic Inscriptions”. The second of these, documentation – together with examination – comprises the core of runological fieldwork. Documentation also applies to the discovery of runic inscriptions. Their uncovering is recorded in find-histories, in most cases, at least nowadays, by archaeologists. The accounts provide information primarily about the runic object itself, and thus contain important material for, among other things, an evaluation of the context of the inscription and an appraisal of its state of completeness and preservation. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 23 June 2009 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: McKinnell, J. and Simek, R. and D¤uwel, K. (2004) 'Runes, magic and religion : a sourcebook.', Vienna: Fassbaender. Studia Medievalia Septentrionalia ; Bd. 10. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.fassbaender.com/index.php?dest=sms10dir=sms Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: The full-text of chapter 12 is available from DRO: McKinnell, J. and Simek, R. and D¤uwel, K. (2004) 'Gods and Mythological Beings in the Younger Futhark' in 'Runes, magic and religion : a sourcebook.', Vienna: Fassbaender, pp. 116-133. Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk 12. Gods and Mythological Beings in the Younger Futhark O. Heathen Gods O 1: Engstad whalebone pin (Nord-Trøndelag, Norway; probably 9th century;→; NIyR 537): )karþâs Garð-Áss (?) ‘Enclosure/Farmstead-god (?)’ This small inscription (2.8 cm long) is on two burnt fragments of a whalebone pin, possibly a weaving shuttle, from a female cremation at the Engstad burial site. -

The S-Rune in the Viking Age and After

JAN MEIJER The s-rune in the Viking age and after i. Introductory In the 16-rune (“normal”) futhark s occupies an exceptional place since it is the only rune that does not — normally — have a full-length mainstaff. This fact is occasionally mentioned by writers on runology but it does not seem to have been more thoroughly discussed. Quite recently Per Stille (1999, 21) drew attention to the exceptional form of the s-rune and suggested the awkwardness involved by the unusual shape of this rune when he says that the s may (my italics) be looked upon as consisting of three branches, the “övre, mellersta och undre” branch (ib., 22). Thompson (1975, 36) points out that s (and i) are the only runes that are not composed of a mainstaff and one or more branches. In the present article I shall first give the sources I used and some numerical data (section 2). After a brief discussion of the old futhark in connection with mainstaffs (3), I will try to give some indications that the lack of a full-length mainstaff may have worried some runog- raphers (4). After this I will briefly comment upon a possible link between the treatment of the s and certain individual runographers (5). A link between the treatment of s and regionality will also shortly be considered (6). The s in the short-branched futhark will get some attention; here I will naturally have to resort to the medieval futhark (7). Finally I will describe a possible relation between the s-type and the material of the inscription-bearer (8). -

Rundatanet Documentation Release 0.1

Rundatanet Documentation Release 0.1 Vadim Frolov Dec 06, 2020 Contents 1 Getting started 3 1.1 Rundata-net................................................3 1.2 Quick user guide.............................................5 2 Database description 11 2.1 Inscription identifier (signature)..................................... 11 2.2 Data in the database........................................... 13 3 Searching 21 3.1 Searching for inscriptions........................................ 21 4 Development and technical information 31 4.1 Development with Docker........................................ 31 4.2 Installation................................................ 31 5 Indices and tables 33 Python Module Index 35 Index 37 i ii Rundatanet Documentation, Release 0.1 Welcome to the version 0.1 of the documentation. Contents 1 Rundatanet Documentation, Release 0.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Getting started 1.1 Rundata-net Rundata-net is a web version of Scandinavian Runic-text Data Base1 (SRDB). It is written in Python/Django and uses JavaScript (jQuery) extensively. The original Rundata app is a desktop application with native support on Windows platform only. I first wrote a cross- platform version, Rundata-qt2, in C++/Qt, but then decided to give a web version a try. Although, to begin with, this was done merely as a proof of concept, Rundata-net now supersedes Rundata-qt. Rundata-net attempts to be a close clone of Rundata. This means that I haven’t tried to fix anything in the database itself. Rundata has a long history. Its functionality may seem limited at the beginning; however, it is still greater than that of Rundata-net. Rundata-net doesn’t support all the kinds of searches that Rundata does. Yet. There is a website running the latest version of Rundata-net. -

Learn to Write Like a Viking

Learn to write like a Viking Vikings didn't use the English alphabet like we do today. They used a system of runes in their writing. Like our alphabet each rune represented a sound when read aloud, but unlike our alphabet each rune had its own meaning Archaeologists call this alphabet Futhark after it’s first 6 letters. Learn about each different rune and have a go at the activity on the next page. Ring with runic inscription © The Trustees of the British Museum fé úr thurs óss reido kaun English: F English: U English: Th English: A English: R English: K, C, G Meaning: Wealth, Cattle or Meaning: Iron or rain Meaning: Giant Meaning: God or river Meaning: Riding Meaning: ulcer Sheep hagall naud isaz ar sol tyr English: H English: N English: I English: a, j English: S English: T, D Meaning: Hail Meaning: Need Meaning: Ice Meaning: Plenty Meaning: Sun Meaning: Spear Futhark in this version ends at yr However you may have noticed some English sounds are missing, notably E, O, P, W. This is because the Vikings mostly didn't use these sounds. How- ever an older version of Futhark does jarken mathr lögr Yr have these letter and I have listed English: B English: M English: L English: R, Y them on the next line. Meaning: Birch tree Meaning: Man Meaning: Sea Meaning: Yew Have a go at the activities on the next page! ehwaz odal peoth wynn English: E English: o English: P English: W, v Meaning: Horse Meaning: Estate Meaning: Fruit tree Meaning: Joy Activities Write your name Have a go at writing you name in runes in the box below.