Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King's Rune Stones

29 Minoru Ozawa King’s Rune Stones A Catalogue with Some Remarks Minoru OZAWA For those who are interested in Danish history the Jelling dynasty from the second half of the 10th century to 1042 has had a special meaning. The successive 6 kings, i.e. Gorm the Old (–958), Harald Bluetooth (–987), Swein Forkbeard (–1014), Harald (–1018), Canute the Great (–1035), and Hardecnut (–1042), transformed a small Danish kingdom into one of the most influential states in Northern Europe in the 11th century.1 After Gorm and Harald made steadier the foundation of the kingdom the following kings expanded their stage of activty westward to gain booty with their army. In 1013 Swein conquered England to take the crown into his hand and, after his sudden death, his son Canute reconquered the kingdom to be the king of England in 1018 and king of Norway later in 1028. At the time the Jelling dynasty reigned over three kingdoms which surrounded the North Sea.2 While it is important to reevaluate the rule of the Jelling dynasty from the viewpoint of European political history, we should remember another important activity by the Danes: raising rune stones in memory of the dead. According to Sawyer’s catalogue, the corpus consisting of 200 rune stones is left to the present days as stones themselves or drawings in early modern age in the territory of medieval 1 Concerning the basic information of the Jelling dynasty, see Thorkild Ramskou, Normannertiden 600–1060. København 1962, pp. 415–; Aksel E. Christensen, Vikingetidens Danmark paa oldhistorisk baggrund. -

University of London Deviant Burials in Viking-Age

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA Ruth Lydia Taylor M. Phil, Institute of Archaeology, University College London UMI Number: U602472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602472 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA The thesis brings together information yielded from archaeology and other sources to provide an overall picture of the types of burial practices encountered during the Viking-Age in Scandinavia. From this, an attempt is made to establish deviancy. Comparative evidence, such as literary, runic, legal and folkloric evidence will be used critically to shed perspective on burial practices and the artefacts found within the graves. The thesis will mostly cover burials from the Viking Age (late 8th century to the mid- 11th century), but where the comparative evidence dates from other periods, its validity is discussed accordingly. Two types of deviant burial emerged: the criminal and the victim. A third type, which shows distinctive irregularity yet lacks deviancy, is the healer/witch burial. -

W Orld Heritage in Denmark and Greenland

Midway between the mounds are the two runic The church between the two mounds is built of calcareous In Denmark, the Heritage Agency of Denmark is responsible stones. The larger stone bears what is probably the tufa (travertine) around 1080-1100. A tower was added for submitting new proposals for inclusion on the World Heritage List. A special committee under UNESCO decides most significant inscription in the history of Denmark: in the 15th century. This church was preceded by three whether to include the proposed candidates on the list. World Heritage in Denmark and Greenland World The Jelling Monuments ‘King Harald bade this monument to be made in wooden churches. The first wooden church was 14 x 30 Being nominated for inclusion on the World Heritage memory of Gorm his father and Thyra his mother, metres somewhat bigger than the present one. It was List does not in itself imply any new form of protection, but it does provide additional recognition and status. that Harald who won for himself all Denmark and presumably built by Harald Bluetooth. It is believed that Norway and made the Danes Christian’. The message his father, King Gorm, was moved from the north mound A worldwide presentation of the cultural and natural is carved on three sides of the large stone. On one and buried in a chambered tomb in the exact place where heritage of mankind is given on UNESCO’s website at www.unesco.org. The world heritage of Greenland is of the sides there is also a carved image of Christ. The the nave and the chancel adjoin. -

Sniðmát Meistaraverkefnis HÍ

MA ritgerð Norræn trú Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell Október 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell 60 einingar Félags– og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Október, 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA-gráðu í Norrænni trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Caroline Elizabeth Oxley, 2019 Prentun: Háskólaprent Reykjavík, Ísland, 2019 Caroline Oxley MA in Old Nordic Religion: Thesis Kennitala: 181291-3899 Október 2019 Abstract Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum: Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view This thesis is a study of animal shape-shifting in Old Norse culture, considering, among other things, the related concepts of hamr, hugr, and the fylgjur (and variations on these concepts) as well as how shape-shifters appear to be associated with the wild, exile, immorality, and violence. Whether human, deities, or some other type of species, the shape-shifter can be categorized as an ambiguous and fluid figure who breaks down many typical societal borderlines including those relating to gender, biology, animal/ human, and sexual orientation. As a whole, this research project seeks to better understand the background, nature, and identity of these figures, in part by approaching the subject psychoanalytically, more specifically within the framework established by the Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, as part of his theory of archetypes. -

Context Analysis and Bracteate Inscriptions in Light of Alternative Iconographic Interpretations

Context analysis and bracteate inscriptions in light of alternative iconographic interpretations Nancy L. Wicker Although nearly 1000 Scandinavian Migration Period (fifth- and sixth-century) gold pendants called bracteates have been discovered in Scandinavia and throughout northern and central Europe, only about twenty percent of these objects have inscriptions. The writing is mostly in the elder futhark but also in corrupted Latin copied from inscriptions on Late Roman coins and medallions, which are presumably the models for bracteate imagery. Relatively few of the 170 bracteates with runic inscriptions—which are known from only 110 different dies (Düwel 2008: 46)—are semantically meaningful. While the research of the late Karl Hauck has dominated bracteate scholarship for the past forty years, his theory of bracteate iconography is not the only possible interpretation of this imagery that may illuminate our understanding of the inscriptions. In this paper, I will high- light other interpretations of bracteates, not as definitive answers to the meaning of bracteates but instead to emphasize the tenuous nature of all such theories. I also propose the use of what Michaela Helmbrecht (2008) has termed ‗context analysis‘ to focus on the various contexts in which bracteates have been discovered in order to shed additional light upon their meaning. Before presenting alternate explanations, I will review basic information about bracteates and their inscriptions, and I will summarize the basic tenets of Hauck‘s thesis. Bracteate classification and iconography From the earliest research on bracteates, scholars including C. J. Thomsen (1855), Oscar Montelius (1869), and Bernhard Salin (1895) focused on organizing these artifacts by classi- fying them into types according to details of images depicted in the central stamped field of decoration. -

Viking-Age Runic Plates of the Runic Plates Have Been Conducted with a Stereomicroscope for This Purpose

The aim of this dissertation is to represent as clearly as possible the genre of Viking- Age runic plates by developing readings and interpretations of the inscriptions on the 46 metal plates with runes from the Viking Age known today. Several investigations SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH • • PERESWETOFF-MORATH SOFIA Viking-Age Runic Plates of the runic plates have been conducted with a stereomicroscope for this purpose. On the basis of the new readings thus established, new interpretations have been pro- posed for the most problematic sections of previously interpreted inscriptions. New interpretations are also offered for inscriptions on runic plates which have previously been considered non-lexical. As well as providing new readings and interpretations, this study has resulted in clarification of the relationship between the form and content of the inscriptions on the runic plates on the one hand and on their find circumstances and appearance on the other. An argued documentation of the readings can be found in an accompanying catalogue in Swedish which is published digitally and can be downloaded as a pdf file at: <http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-383584> Viking-Age Runic Plates Viking-Age Distribution: Sofia Pereswetoff-Morath eddy.se ab e-post: [email protected] ISSN 0065-0897 and Box 1310, 621 24 Visby. Telefon: 0498-25 39 00 ISSN 1100-1690 http://kgaa.bokorder.se ISBN 978-91-87403-33-0 1 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI 155 Runrön 21 Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 2 3 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI CLV Runrön 21 Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH Viking-Age Runic Plates Readings and Interpretations Translated from Swedish by Mindy MacLeod UPPSALA 2019 Kungl. -

Copyright by Collin Laine Brown 2018

Copyright by Collin Laine Brown 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Collin Laine Brown Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: CONVERSION, HERESY, AND WITCHCRAFT: THEOLOGICAL NARRATIVES IN SCANDINAVIAN MISSIONARY WRITINGS Committee: Marc Pierce, Supervisor Peter Hess Martha Newman Troy Storfjell Sandra Straubhaar CONVERSION, HERESY, AND WITCHCRAFT: THEOLOGICAL NARRATIVES IN SCANDINAVIAN MISSIONARY WRITINGS by Collin Laine Brown Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2018 Dedication Soli Deo gloria. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge my wife Robin. She especially helped me through the research and writing process, and kept me sane through the stress of having to spend so much time away from her while in graduate school. I wish that my late father Doug could be here, and I know that he would be thrilled to see me receive my PhD. It was his love of history that helped set me on the path I find myself today. My academic family has also been amazing during my time in graduate school. Good friends were always there to keep me motivated and stimulate my research. The professors involved in my project are also much deserving of my thanks: Marc Pierce, my advisor, as well as Sandra Straubhaar, Peter Hess, Martha Newman, and Troy Storfjell. I am grateful for their help and support, and for the opportunity to embark on this very interdisciplinary and very fulfilling project. -

The Rok Inscription, Line 20

The Rok Inscription, Line 20 Joseph Harris h a r v a r d u n i v e r s i t y In memory of Frederic Amory The only severely damaged line on the Rok Stone is the one numbered 20 in the now standard treatment of Elias Wessen.1 According to Wessen and most subsequent interpreters, line 20 was to be read after his 19 and before his 2 1-2 8 ; in two of my articles on Rok I have followed and defended this order (though ultimately calling for a reversal of 27-28), but I did not attempt in those articles to comment extensively on the damaged line.2 The present small-scale study in memory of a large-minded friend essays a reconstruction and inter pretation of line 20, building on the conclusions and utilizing the conventions of those two articles, as well, of course, as on those of my predecessors.3 As previous scholars have noted, an understanding 1. Elias Wessen, Runstenen vid Roks kyrka, Kungl. vitterhets historie och antikvitets akademiens handlingar, filologisk-filosofiska serien 5 (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1958). Line 26, side D, suffered the total loss of its first rune (coordinates cipher), but completion of the word there is non-controversial. 2 . See Joseph Harris, “Myth and Meaning in the Rok Inscription,” Viking and Medi eval Scandinavia 2 (2006): 45-109 (line 20 is discussed chiefly pp. 51-52), and “ The Rok Stone through Anglo-Saxon Eyes,” in The Anglo-Saxons and the North, ed. Matti Kilpio et al. (Tempe, AZ: ACMRS, 2009), 11-45. -

Runestone Images and Visual Communication

RUNESTONE IMAGES AND VISUAL COMMUNICATION IN VIKING AGE SCANDINAVIA MARJOLEIN STERN, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy JULY 2013 Abstract The aim of this thesis is the visual analysis of the corpus of Viking Age Scandinavian memorial stones that are decorated with figural images. The thesis presents an overview of the different kinds of images and their interpretations. The analysis of the visual relationships between the images, ornamentation, crosses, and runic inscriptions identifies some tendencies in the visual hierarchy between these different design elements. The contents of the inscriptions on runestones with images are also analysed in relation to the type of image and compared to runestone inscriptions in general. The main outcome of this analysis is that there is a correlation between the occurrence of optional elements in the inscription and figural images in the decoration, but that only rarely is a particular type of image connected to specific inscription elements. In this thesis the carved memorial stones are considered as multimodal media in a communicative context. As such, visual communication theories and parallels in commemoration practices (especially burial customs and commemorative praise poetry) are employed in the second part of the thesis to reconstruct the cognitive and social contexts of the images on the monuments and how they create and display identities in the Viking Age visual communication. Acknowledgements Many people have supported and inspired me throughout my PhD. I am very grateful to my supervisors Judith Jesch and Christina Lee, who have been incredibly generous with their time, advice, and bananas. -

The Tourist's Book of Runestones

The tourist’s book of runestones c:\documenti\runstenar\runresa\italyUSA\010106 1 c:\documenti\runstenar\runresa\italyUSA\010106 2 CONTENTS Sweden Italy The USA Runmaster Eriksgata References c:\documenti\runstenar\runresa\italyUSA\010106 3 SWEDEN c:\documenti\runstenar\runresa\italyUSA\010106 4 SOME NAMES Ålstorp Stentoften Getinge Fallo Vestra Strö Runamo Kareby Eksjö Stora Harrie Björkeporp Velanda Nömme Östra Gårdstånga Skällenäs Månstadskulle Björkö Holmby Karlevi Störa Västölet Brahe k:a Hällestad Resmo Södra Kedum Kumlaby Skårby Björn Flisa Ryda Brahe sk:a Dagstorp Seby Levene Ödeshög Örja Sandby Sparlösa Häggestad Holmby Gårdby Slädene Heda Bösarp Bjärby Håle Rök Allhelgona Lerkaka Särestad Kvarntorp Lundagård Bogby Kållands-Åsaka Svanshal Gårdstånga 2 Bägby Skalunda Haddestad Valleberga Köping Råda Kumla Skivarp Tings Flisa Källby-Hallar Gärdlösa Norra Nöbbelöv Transjö Husaby Karleby Gårdstånga 3 Sandsjö Sunnevad Harstad Valkärra Ingelige Hög Leksberg Väderstad Hjärup Nöbbele Karleby Ekeby Vismarlöv Enet Stora Ek Strålsnäs Fosia Sjöbylund Frölunda Grönlund Fuglie Växsjö Mellongarden Sörby Fuglie Hög Aringsås Norra Lundby Högby Bösarp Ivla Dagsnäs Västra Skrukeby Jordberga Bolmaryd Norra Vånga Axstad Tulltorp Rörbro Postgården Bjälbo Östra Bräkentorp Härlingstorp Appuna Vämmenhög Replösa Ballstorp Hov Sjörup Tuna Larvs Hed Vadstena Västra Nöbbelöv Ryssby Bitterna Vestra Stenby Solberga Skaftarp Skånum Kälvesten Orsjö Runstensholm Vårkumla Vinnerstad Rydsgård Nävelsjö Olsbro Fornåsa Skårby Vetlanda Bröstig Örevad Bjärnäs Bäckseda -

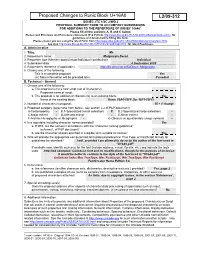

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4. -

THE NINE DOORS of MIDGARD a Curriculum of Rune-Work

,. , - " , , • • • • THE NINE DOORS OF MmGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work - • '. Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin·Drighten of the Rune-Gild THE NINE DOORS OF MIDGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin-Drighten of the Rune-Gild 1997 - Introduction This work is the first systematic introduction to Runelore available in many centuries. This age requires and allows some new approaches to be sure. We have changed over the centuries in question. But at the same time we are as traditional as possible. The Gild does not fear innovation - in fact we embrace it - but only after the tradition has been thoroughly examined for all it has to offer. Too often in the history of the runic revival various proponents have actually taken their preconceived notions about what the Runes should say- and then "runicized" them. We avoid this type of pseudo-innovation at all costs. Our over-all magical method is a simple one. The tradition posits an outer world (objective reality) and an inner-world (subjective reality). The work of the Runer is the exploration of both of these worlds for what they have to offer in the search for wisdom. In learning the Runes, the Runer synthesizes all the objective lore and tradition he can find on the Runes with his subjective experience. In this way he "makes the Runes his own." All the Runes and their overall system are then used as a sort of "meta-Ianguage" in meaningful communication between these objective and subjective realities. The Runer may wish to be active in this communication - to cause changes to occur in accordance with his will, or he may wish to learn from one of these realities some information which would normally be hidden from him.