King's Rune Stones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handbook for International Programs at the Danish School of Media and Journalism, Copenhagen Campus

October 14 Handbook for International Programs at the Danish School of Media and Journalism, Copenhagen Campus 1 WELCOME TO DANISH SCHOOL OF MEDIA AND JOURNALISM 4 THE INDUSTRY SEAL OF APPROVAL 4 OTHER ACTIVITIES 4 THE COURSES 4 ATTENDANCE AND GRADING 4 ATTENDANCE IS MANDATORY 4 GRADING 4 COMPARATIVE TABLE OF GRADING SYSTEMS 5 AT DMJX 5 COMPUTERS AND E-MAIL 5 PHOTOCOPIERS 6 LIBRARY 6 CLASS ROOMS 6 DANISH LANGUAGE COURSE 6 TEACH YOURSELF DANISH - ONLINE 6 THINGS TO DO BEFORE ARRIVAL IN DENMARK 6 GRANTS AND SCHOLARSHIPS 6 INSURANCE 7 ACCOMMODATION IN COPENHAGEN 7 OFFICIAL PAPERS 8 RESIDENCE PERMIT 8 EMBASSIES 8 CIVIL PERSONAL REGISTRATION NUMBER 8 HOW TO APPLY FOR A CPR NUMBER 8 CHANGE OF ADDRESS 8 PRACTICALITIES 9 MOBILE PHONES 9 BANKS AND CREDIT CARDS 9 SENDING PARCELS TO DENMARK 9 TRANSPORT IN DENMARK 9 BUDGET & FINANCES 9 TAXATION 10 OTHER INFORMATION 10 PACKING YOUR SUITCASE 10 OTHER USEFUL THINGS: 10 JOB VACANCIES 11 2 NICE TO KNOW 11 FACTS ABOUT DENMARK 11 FRIENDS AND FAMILY DROPPING IN? 15 USEFUL LINKS FOR INFORMATION ABOUT DENMARK & COPENHAGEN 15 WEATHER 15 3 Welcome to Danish School of Media and Journalism A warm welcome to the Danish School of Media and Journalism (DMJX) and a new environment that hopefully will give you both professional and social challenges over the next semester. Our goal is to give you the best basis for both a professional and a social development. The industry seal of approval All programmes are very vocational and built on tasks which closely reflect the real world. -

The-Vikings-Teachers-Information-Pack.Pdf

Teacher’s Information Pack produced by the Learning and Visitor Services Department, Tatton Park, Knutsford, WA16 6QN. www.tattonpark.org.uk Page 1 of 26 Contents Page(s) The Age of the Vikings 3 - 5 Famous Vikings (including Ivarr the Boneless) 6 - 7 Viking Costume 8 Viking Ships 9 Viking Gods 10 - 12 Viking Food 13 - 14 Useful books and websites 15 Appendix 1 – Ivarr the Boneless Lesson Plan 16 - 17 Appendix 2 – Viking Runes 18 Appendix 3 – Colouring Sheets 19 - 20 Appendix 4 – Wordsearch 21 Page 2 of 26 Page 3 of 26 The Age of the Vikings From the eighth to the eleventh centuries, Scandinavians, mostly Danes and Norwegians, figure prominently in the history of Western Europe as raiders, conquerors, and colonists. They plundered extensively in the British Isles and France and even attacked as far south as Spain, Portugal and North Africa. In the ninth century they gained control of Orkney, Shetland and most of the Hebrides, conquered a large part of England and established bases on the Irish coast from which they launched attacks within Ireland and across the Irish Sea. Men and women from west Scandinavia emigrated to settle, not only in the parts of the British Isles that were then under Scandinavian control, but also in the Faeroes and Iceland, which had previously been uninhabited. In the last years of the tenth century they also began to colonize Greenland, and explored North America, but without establishing a permanent settlement there. The Scandinavian assault on Western Europe culminated in the early eleventh century with the Danish conquest of the English kingdom, an achievement that other Scandinavian kings attempted to repeat later in the century, but without success. -

W Orld Heritage in Denmark and Greenland

Midway between the mounds are the two runic The church between the two mounds is built of calcareous In Denmark, the Heritage Agency of Denmark is responsible stones. The larger stone bears what is probably the tufa (travertine) around 1080-1100. A tower was added for submitting new proposals for inclusion on the World Heritage List. A special committee under UNESCO decides most significant inscription in the history of Denmark: in the 15th century. This church was preceded by three whether to include the proposed candidates on the list. World Heritage in Denmark and Greenland World The Jelling Monuments ‘King Harald bade this monument to be made in wooden churches. The first wooden church was 14 x 30 Being nominated for inclusion on the World Heritage memory of Gorm his father and Thyra his mother, metres somewhat bigger than the present one. It was List does not in itself imply any new form of protection, but it does provide additional recognition and status. that Harald who won for himself all Denmark and presumably built by Harald Bluetooth. It is believed that Norway and made the Danes Christian’. The message his father, King Gorm, was moved from the north mound A worldwide presentation of the cultural and natural is carved on three sides of the large stone. On one and buried in a chambered tomb in the exact place where heritage of mankind is given on UNESCO’s website at www.unesco.org. The world heritage of Greenland is of the sides there is also a carved image of Christ. The the nave and the chancel adjoin. -

Wars Between the Danes and Germans, for the Possession Of

DD 491 •S68 K7 Copy 1 WARS BETWKEX THE DANES AND GERMANS. »OR TllR POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. BV t>K()F. ADOLPHUS L. KOEPPEN FROM THE "AMERICAN REVIEW" FOR NOVEMBER, U48. — ; WAKS BETWEEN THE DANES AND GERMANS, ^^^^ ' Ay o FOR THE POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. > XV / PART FIRST. li>t^^/ On feint d'ignorer que le Slesvig est une ancienne partie integTante de la Monarchie Danoise dont I'union indissoluble avec la couronne de Danemarc est consacree par les garanties solennelles des grandes Puissances de I'Eui'ope, et ou la langue et la nationalite Danoises existent depuis les temps les et entier, J)lus recules. On voudrait se cacher a soi-meme au monde qu'une grande partie de la popu- ation du Slesvig reste attacliee, avec une fidelite incbranlable, aux liens fondamentaux unissant le pays avec le Danemarc, et que cette population a constamment proteste de la maniere la plus ener- gique centre une incorporation dans la confederation Germanique, incorporation qu'on pretend medier moyennant une armee de ciuquante mille hommes ! Semi-official article. The political question with regard to the ic nation blind to the evidences of history, relations of the duchies of Schleswig and faith, and justice. Holstein to the kingdom of Denmark,which The Dano-Germanic contest is still at the present time has excited so great a going on : Denmark cannot yield ; she has movement in the North, and called the already lost so much that she cannot submit Scandinavian nations to arms in self-defence to any more losses for the future. The issue against Germanic aggression, is not one of a of this contest is of vital importance to her recent date. -

The Royal Roots of Clan Fleming Trace Fleeman © Astral Scribes™ 2013

The Royal Roots of Clan Fleming Trace Fleeman © Astral Scribes™ 2013. All rights reserved. The history of Clan Fleming is a long one. The clan was formed by Baldwin, a man from Flanders (conspicuously the French region of such), after he received a multiplicity of land grants from David I, in Lanarkshire. Baldwin himself was born to Knut de Flanders, who, according to Saxo Grammaticus in his work Gesta Danorum, was born to Folke the Fat, "the most powerful man in Sweden". Knut was bore by Ingrid Knutsdotter, the wife of Folke, who herself was the spawn of the Danish sovereign Canute IV, the patron saint of Denmark, making Ingrid herself princess of Denmark. Canute IV, who only ruled on the Danish throne for 6 years, was born to Sweyn II of Denmark & an unidentified concubine. Sweyn was born to Ulf, a jarl of Denmark and Viking chieftain. Canute's grandfather, Ulf Thorgilsson, was son of Thorgil Styrbjörnsson Sprakling, himself son of Styrbjörn the Strong. Thorgil was son of Olof (II) Björnsson, a semi-legendary Swedish king, who according to Hervarar saga and the Styrbjarnar þáttr Svíakappa ruled together with his brother Eric the Victorious. Other notable relatives of Sweyn are Sweyn Forkbeard, his grandfather, son of King Harald Bluetooth of Denmark, who ruled Denmark and England, as well as parts of Norway. Harald Bluetooth, king of Denmark and Norway, was born to Gorm the Old. Gorm was born to Harthacnut. Adam of Bremen, a German raconteur, makes Harthacnut son of an otherwise unfamiliar king Sweyn, while the chronicle Ragnarssona þáttr makes him son of the semi-mythic viking tribal chief Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye, himself one of the sons of the mythicy Ragnar Lodbrok. -

Pagan to Christian

FROM ODIN TO CHRIST Pagan to Christian o the Vikings living and travel- ling in a Europe that was almost entirely Christian, con- version did not come äs a single explosive event. If we think of the earlier Situation in England, where Christianity obliterated virtually all recorded knowledge of pagan thought and practice, the way in which some Norsemen remained coolly balanced between two re- ligions, examining the merits of both, and in some cases trying to get the protective benefits of both, is a fascinating study. It is presum- ably one of the results of this detachment, that even after conversion there is still this willingness among the converted to re- member and write about paganism rather than discarding it simply äs error, idolatry and devil-worship. The transition period between paganism and Christianity leaves traces in carving, literature and metalwork. Whether Vikings first started to wear a Thor's hammer round their necks because Christians wore pendant crosses and crucifixes, or whether the tradi- tion is independent of Christian influence, cannot now be determined. But certainly there was enough of a market for both for one enterprising smith to leave behind him in Denmark a single soapstone mould for the production of both cross and hammer amu- lets. Most of the surviving pendants are clearly identifiable äs either hammer or cross, but there are examples where the design of the one seems to have influenced the other, even one example where we are not sure which it was meant to be. Whether the canny Viking who wore it intended the ambiguity is not certain. -

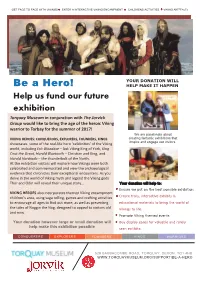

Be a Hero! Donation Form

GET FACE TO FACE WITH VIKINGS ENTER A INTERACTIVE VIKING ENCAMPMENT CHILDRENS ACTIVITIES VIKING ARTEFACTS YOUR DONATION WILL Be a Hero! HELP MAKE IT HAPPEN Help us fund our future exhibition Torquay Museum in conjunction with The Jorvick Group would like to bring the age of the heroic Viking warrior to Torbay for the summer of 2017! We are passionate about VIKING HEROES: CONQUERORS, EXPLORERS, FOUNDERS, KINGS creating fantastic exhibitions that showcases some of the real-life hero ‘celebrities’ of the Viking inspire and engage our visitors. world, including Eric Bloodaxe – last Viking King of York, King Cnut the Great, Harald Bluetooth – Christian and King, and Harald Hardrada – the thunderbolt of the North. At the exhibition visitors will explore how Vikings were both celebrated and commemorated and view the archaeological evidence that chronicles their exceptional encounters. As you delve in the world of Viking myth and legend the Viking gods Thor and Odin will reveal their unique story… Your donation will help to: Ensure we put on the best possible exhibition VIKING HEROES also incorporates themed Viking encampment Create trails, interactive exhibits & children’s area, using saga telling, games and crafting activities to encourage all ages to find out more, as well as presenting educational materials to bring the world of the tales of Noggin the Nog, designed to appeal to visitors old Vikings to life. and new. Promote Viking themed events Your donation however large or small donation will Buy display cases for valuable and rarely help make this exhibition possible seen exhibits. CONQUERERS EXPLORERS FOUNDERS KINGS WARRIORS 529 BABBACOMBE ROAD, TORQUAY, DEVON. -

Ars Betweek the Danes and Germ for We: Possession of Schles/Wig

WARS B ETWEEN THE DAN ES AND G ERMAN S IN F LE FOR TH E POSSESS O O SCH SWIG . IR T P ART F S . ’ On feint d ignorer que le Slesvig est une ancienne partie intégrante de la M onarchi e Danoise dont ’ l union indi ssoluble avec la couronne de D anemarc est consacrée par les garanties solennelles de s ’ an es Pui ssance s de l Eur o e et oh la an e et la ationali anoises e i s e de ui sl es em s l gr d p , l gu n té D x t nt p t p es ‘ - mem e et au m on e en ie u une n us ecu s. On ou r ai se cache asc i a e artie de l l r lé v d t r d t r, q gr d p a popu I ' l ‘ pa i on du esvi es e a tach e a ec un e fide hte mébranlable aux iens on amen a nissan le t Sl g r t t é , v , l f d t ux u t a s a ec le D anemarc e t ue ce e o ul ation a cons amme o es de l a mani ére la us éner p y v , q tt p p t nt pr t té pl ’ i ue con r e une inco o a io ans la confederation G e mani ue inco o a io on en m g q t rp r t n d r q , rp r t n qu prét d édi er n ommes — emi - ci al article moyenna t une armée de cinquante mill e h l S qfi . -

Rune Carvers and Sponsor Families on Bornholm

DANISH JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY 2019, VOL 8, 1-21 1 Rune Carvers and Sponsor Families on Bornholm Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt1 and Lisbeth M. Imer2 1 (Corresponding author) Swedish National Heritage Board, PO Box 1114, 621 22 Visby, Sweden ([email protected]) ORCID: 0000-0001-8364-59-52 2 Nationalmuseet, Frederiksholms Kanal 12, 1220 København K, Denmark ([email protected]) ORCID: 0000-0003-4895-1916 ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The runestones on Bornholm have for a long time aroused discussion due to their singular Received 09 April 2019; character and dating as compared to most runestones in other parts of Denmark. In this Accepted 12 Sep- paper, the relations between sponsors and rune carvers have been investigated through tember 2019 analysis of the carving technique by means of the first 3D-scanning and multivariate statisti- KEYWORDS cal analysis ever carried out on the Danish runestone material. The results indicate that the Runestone; Bornholm; carvers were attached to the sponsor families and that the carvers were probably members 3D-scanning; Rune of those families. During the fieldwork, a fragment of a previously unknown runestone was carver; Sponsor; documented in the church of St. Knud. Carving technique Introduction identity. A completely different source of evidence will be used here, namely the carving technique, When the runestones of Bornholm were raised, which will be studied by 3D-scanning and multi- the practice of erecting runestones had already de- variate statistical methods, following a method de- creased dramatically in other Danish areas, where veloped at the Archaeological Research Laboratory, the number of runestones had fallen to the same lev- Stockholm University (Kitzler Åhfeldt 2002) and el as before around 965, when the king claimed to further refined in various research projects (e.g. -

Schulte M. the Scandinavian Dotted Runes

UDC 811.113.4 Michael Schulte Universitetet i Agder, Norge THE SCANDINAVIAN DOTTED RUNES For citation: Schulte M. The Scandinavian dotted runes. Scandinavian Philology, 2019, vol. 17, issue 2, pp. 264–283. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu21.2019.205 The present piece deals with the early history of the Scandinavian dotted runes. The medieval rune-row or fuþork was an extension of the younger 16-symbol fuþark that gradually emerged at the end of the Viking Age. The whole inventory of dotted runes was largely complete in the early 13th century. The focus rests on the Scandina- vian runic inscriptions from the late Viking Age and the early Middle Ages, viz. the period prior to AD 1200. Of particular interest are the earliest possible examples of dotted runes from Denmark and Norway, and the particular dotted runes that were in use. Not only are the Danish and Norwegian coins included in this discussion, the paper also reassesses the famous Oddernes stone and its possible reference to Saint Olaf in the younger Oddernes inscription (N 210), which places it rather safely in the second quarter of the 11th century. The paper highlights aspects of absolute and rela- tive chronology, in particular the fact that the earliest examples of Scandinavian dot- ted runes are possibly as early as AD 970/980. Also, the fact that dotted runes — in contradistinction to the older and younger fuþark — never constituted a normative and complete system of runic writing is duly stressed. In this context, the author also warns against overstraining the evidence of dotted versus undotted runes for dating medieval runic inscriptions since the danger of circular reasoning looms large. -

Family Group Sheet for Cnut the Great

Family Group Sheet for Cnut the Great Husband: Cnut the Great Birth: Bet. 985 AD–995 AD in Denmark Death: 12 Nov 1035 in England (Shaftesbury, Dorset) Burial: Old Minster, Winchester. Bones now in Winchester Cathedral Father: King Sweyn I Forkbeard Mother: Wife: Emma of Normandy Birth: 985 AD Death: 06 Mar 1052 in Winchester, Hampshire Father: Richard I Duke of Normandy Mother: Gunnor de Crepon Children: 1 Name: Gunhilda of Denmark F Birth: 1020 Death: 18 Jul 1038 Spouse: Henry III 2 Name: Knud III Hardeknud M Birth: 1020 in England Death: 08 Jun 1042 in England Burial: Winchester Cathedral, Winchester, England Notes Cnut the Great Cnut the Great From Wikipedia, (Redirected from Canute the Great) Cnut the Great King of all the English, and of Denmark, of the Norwegians, and part of the Swedes King of Denmark Reign1018-1035 PredecessorHarald II SuccessorHarthacnut King of all England Reign1016-1035 PredecessorEdmund Ironside SuccessorHarold Harefoot King of Norway Reign1028-1035 PredecessorOlaf Haraldsson SuccessorMagnus Olafsson SpouseÆlfgifu of Northampton Emma of Normandy Issue Sweyn Knutsson Harold Harefoot Harthacnut Gunhilda of Denmark FatherSweyn Forkbeard MotherSigrid the Haughty also known as Gunnhilda Bornc. 985 - c. 995 Denmark Died12 November 1035 England (Shaftesbury, Dorset) BurialOld Minster, Winchester. Bones now in Winchester Cathedral Cnut the Great, also known as Canute or Knut (Old Norse: Knútr inn ríki[1] (c. 985 or 995 - 12 November 1035) was a Viking king of England and Denmark, Norway, and parts of Sweden, whose successes as a statesman, politically and militarily, prove him to be one of the greatest figures of medieval Europe and yet at the end of the historically foggy Dark Ages, with an era of chivalry and romance on the horizon in feudal Europe and the events of 1066 in England, these were largely 'lost to history'. -

Runestone Images and Visual Communication

RUNESTONE IMAGES AND VISUAL COMMUNICATION IN VIKING AGE SCANDINAVIA MARJOLEIN STERN, MA Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy JULY 2013 Abstract The aim of this thesis is the visual analysis of the corpus of Viking Age Scandinavian memorial stones that are decorated with figural images. The thesis presents an overview of the different kinds of images and their interpretations. The analysis of the visual relationships between the images, ornamentation, crosses, and runic inscriptions identifies some tendencies in the visual hierarchy between these different design elements. The contents of the inscriptions on runestones with images are also analysed in relation to the type of image and compared to runestone inscriptions in general. The main outcome of this analysis is that there is a correlation between the occurrence of optional elements in the inscription and figural images in the decoration, but that only rarely is a particular type of image connected to specific inscription elements. In this thesis the carved memorial stones are considered as multimodal media in a communicative context. As such, visual communication theories and parallels in commemoration practices (especially burial customs and commemorative praise poetry) are employed in the second part of the thesis to reconstruct the cognitive and social contexts of the images on the monuments and how they create and display identities in the Viking Age visual communication. Acknowledgements Many people have supported and inspired me throughout my PhD. I am very grateful to my supervisors Judith Jesch and Christina Lee, who have been incredibly generous with their time, advice, and bananas.