Bandrúnir in Icelandic Sagas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Uniform Was the Old Norse Religion?

II. Old Norse Myth and Society HOW UNIFORM WAS THE OLD NORSE RELIGION? Stefan Brink ne often gets the impression from handbooks on Old Norse culture and religion that the pagan religion that was supposed to have been in Oexistence all over pre-Christian Scandinavia and Iceland was rather homogeneous. Due to the lack of written sources, it becomes difficult to say whether the ‘religion’ — or rather mythology, eschatology, and cult practice, which medieval sources refer to as forn siðr (‘ancient custom’) — changed over time. For obvious reasons, it is very difficult to identify a ‘pure’ Old Norse religion, uncorroded by Christianity since Scandinavia did not exist in a cultural vacuum.1 What we read in the handbooks is based almost entirely on Snorri Sturluson’s representation and interpretation in his Edda of the pre-Christian religion of Iceland, together with the ambiguous mythical and eschatological world we find represented in the Poetic Edda and in the filtered form Saxo Grammaticus presents in his Gesta Danorum. This stance is more or less presented without reflection in early scholarship, but the bias of the foundation is more readily acknowledged in more recent works.2 In the textual sources we find a considerable pantheon of gods and goddesses — Þórr, Óðinn, Freyr, Baldr, Loki, Njo3rðr, Týr, Heimdallr, Ullr, Bragi, Freyja, Frigg, Gefjon, Iðunn, et cetera — and euhemerized stories of how the gods acted and were characterized as individuals and as a collective. Since the sources are Old Icelandic (Saxo’s work appears to have been built on the same sources) one might assume that this religious world was purely Old 1 See the discussion in Gro Steinsland, Norrøn religion: Myter, riter, samfunn (Oslo: Pax, 2005). -

THOR and the GIANT's BRIDE by Riti Kroesen

THOR AND THE GIANT'S BRIDE by Riti Kroesen - Leiden When the first Scandinavian settlers arrived in Iceland, there was one god, whom they loved and worshipped above all others: Thor. The testimony of the Islendinga Spgur is abundantly clear on this point. Though we cannöt deal extensively with it here, these texts are amply supported by other evidence, both direct and indirect, Icelandic as weIl as non-Icelandic. It seems that in the beginning Thor was revered more than the other gods in at least large parts of Scandinavia.1 On the other hand, we have the stories of the two Eddas2, in which Thor generally plays a subordinate part and even cuts a sorry figure; sometimes he seems to be present only as a source of fun for both gods and men due to his silliness and lack of brains. His rashness is apt to cause hirn continual trouble, and his enormous appetite makes everybody shudder. But true - he is still the best fighter of all the gods - and he is the most htmest of them all, one might like to add. In the Eddas, Odin is the most important and in some in- stances the omnipotent god, the father and king of all gods and men. The explanation of this, which has often been given before, is that Odin must have pushed Thor to the background, at least in court-circles. Odin, the old god of war and death, was the protector of both the Danish and Norwegian kings - the latter from the southern part of Norway and like their Danish colleagues 1. -

Viking-Age Runic Plates of the Runic Plates Have Been Conducted with a Stereomicroscope for This Purpose

The aim of this dissertation is to represent as clearly as possible the genre of Viking- Age runic plates by developing readings and interpretations of the inscriptions on the 46 metal plates with runes from the Viking Age known today. Several investigations SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH • • PERESWETOFF-MORATH SOFIA Viking-Age Runic Plates of the runic plates have been conducted with a stereomicroscope for this purpose. On the basis of the new readings thus established, new interpretations have been pro- posed for the most problematic sections of previously interpreted inscriptions. New interpretations are also offered for inscriptions on runic plates which have previously been considered non-lexical. As well as providing new readings and interpretations, this study has resulted in clarification of the relationship between the form and content of the inscriptions on the runic plates on the one hand and on their find circumstances and appearance on the other. An argued documentation of the readings can be found in an accompanying catalogue in Swedish which is published digitally and can be downloaded as a pdf file at: <http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-383584> Viking-Age Runic Plates Viking-Age Distribution: Sofia Pereswetoff-Morath eddy.se ab e-post: [email protected] ISSN 0065-0897 and Box 1310, 621 24 Visby. Telefon: 0498-25 39 00 ISSN 1100-1690 http://kgaa.bokorder.se ISBN 978-91-87403-33-0 1 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI 155 Runrön 21 Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 2 3 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI CLV Runrön 21 Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH Viking-Age Runic Plates Readings and Interpretations Translated from Swedish by Mindy MacLeod UPPSALA 2019 Kungl. -

Economy, Magic and the Politics of Religious Change in Pre-Modern

1 Economy, magic and the politics of religious change in pre-modern Scandinavia Hugh Atkinson Department of Scandinavian Studies University College London Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 28th May 2020 I, Hugh Atkinson, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that these sources have been acknowledged in the thesis. 2 Abstract This dissertation undertook to investigate the social and religious dynamic at play in processes of religious conversion within two cultures, the Sámi and the Scandinavian (Norse). More specifically, it examined some particular forces bearing upon this process, forces originating from within the cultures in question, working, it is argued, to dispute, disrupt and thereby counteract the pressures placed upon these indigenous communities by the missionary campaigns each was subjected to. The two spheres of dispute or ambivalence towards the abandonment of indigenous religion and the adoption of the religion of the colonial institution (the Church) which were examined were: economic activity perceived as unsustainable without the 'safety net' of having recourse to appeal to supernatural powers to intervene when the economic affairs of the community suffered crisis; and the inheritance of ancestral tradition. Within the indigenous religious tradition of the Sámi communities selected as comparanda for the purposes of the study, ancestral tradition was embodied, articulated and transmitted by particular supernatural entities, personal guardian spirits. Intervention in economic affairs fell within the remit of these spirits, along with others, which may be characterized as guardian spirits of localities, and guardian spirits of particular groups of game animals (such as wild reindeer, fish). -

Performance and Norse Poetry: the Hydromel of Praise and the Effluvia of Scorn the Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lecture for 2001

Oral Tradition, 16/1 (2001): 168-202 Performance and Norse Poetry: The Hydromel of Praise and the Effluvia of Scorn The Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lecture for 2001 Stephen A. Mitchell Performance Studies and the Possibilities for Interpretation How should we moderns “read” a medieval text?1 Thanks to the work of many scholars, not least the pioneering studies of Milman Parry and Albert Lord, we are today able to understand the nature and implications of a preserved medieval work’s background as an oral text much better than did the early and brilliant (but narrowly gauged) generations that included such giants within Old Norse as Jacob Grimm, Konrad von Maurer, Theodor Möbius, Rudolf Keyser, and N. M. Petersen.2 Given these advances in our understanding of orality, performance, and the ethnography of speaking, how do we decode the social, religious, and literary worlds of northern 1 By “read” I mean here the full range of decocting techniques employed by modern scholarship, including but not limited to those associated with traditional philology and folkloristics, as well as such emergent approaches as those collectively known as “cultural studies.” This essay was delivered as the 2001 Albert Lord/Milman Parry Memorial Lecture under the sponsorship of the Center for Studies in Oral Tradition at the University of Missouri. For their encouragement, sage comments, and helpful criticism, I warmly thank John Foley, Joseph Harris, Gregory Nagy, and John Zemke. 2 Already as Parry was in the early stages of his research project in the Balkans, he envisioned its implications for the older works of northern Europe: “My purpose in undertaking the study of this poetry was as follows. -

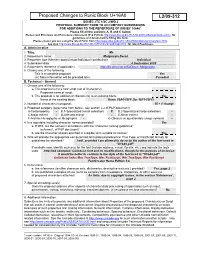

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4. -

The Prose Edda: Tales from Norse Mythology, , University of California Press, 2001, 0520234774, 9780520234772, 131 Pages

The Prose Edda: Tales from Norse Mythology, , University of California Press, 2001, 0520234774, 9780520234772, 131 pages. Prose Edda is a work without predecessor or parallel. Snorri Sturluson feared that the traditional techniques of Norse poetics, the pagan kennings, and the allusions to mythology would be forgotten with the introduction of new verse forms from Europe. Prose Edda was designed as a handbook for poets to compose in the style of the skalds of the Viking ages. It is an exposition of the rule of poetic diction with many examples, applications, and retellings of myths and legends. The present selection includes the whole of Gylfaginning (The deluding of Gylfi)--a guide to mythology that forms one of the great storybooks of the Middle Ages--and the longer heroic tales and legends of SkГЎldskaparmГЎl (Poetic diction). Snorri Sturluson was a master storyteller, and this translation in modern idiom of the inimitable tales of the gods and heroes of the Scandinavian peoples brings them to life again.. DOWNLOAD HERE Thunder of the Gods , Dorothy Hosford, 1957, , . The Poetic Edda The Mythological Poems, Henry Adams Bellows, 2004, Fiction, 251 pages. The vibrant Old Norse poems in this 13th-century collection known as the 'Lays of the Gods' recapture the ancient oral traditions of the Norsemen. These mythological poems .... The Prose Or Younger Edda Commonly Ascribed to Snorri Sturluson, Snorri Sturluson, 1842, Literary Criticism, 115 pages. Njal's Saga , , 1997, Fiction, 416 pages. Njal's Saga is the finest of the Icelandic sagas, and one of the world's greatest prose works. Written c.1280, about events a couple of centuries earlier, it is divided into ... -

THE NINE DOORS of MIDGARD a Curriculum of Rune-Work

,. , - " , , • • • • THE NINE DOORS OF MmGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work - • '. Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin·Drighten of the Rune-Gild THE NINE DOORS OF MIDGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin-Drighten of the Rune-Gild 1997 - Introduction This work is the first systematic introduction to Runelore available in many centuries. This age requires and allows some new approaches to be sure. We have changed over the centuries in question. But at the same time we are as traditional as possible. The Gild does not fear innovation - in fact we embrace it - but only after the tradition has been thoroughly examined for all it has to offer. Too often in the history of the runic revival various proponents have actually taken their preconceived notions about what the Runes should say- and then "runicized" them. We avoid this type of pseudo-innovation at all costs. Our over-all magical method is a simple one. The tradition posits an outer world (objective reality) and an inner-world (subjective reality). The work of the Runer is the exploration of both of these worlds for what they have to offer in the search for wisdom. In learning the Runes, the Runer synthesizes all the objective lore and tradition he can find on the Runes with his subjective experience. In this way he "makes the Runes his own." All the Runes and their overall system are then used as a sort of "meta-Ianguage" in meaningful communication between these objective and subjective realities. The Runer may wish to be active in this communication - to cause changes to occur in accordance with his will, or he may wish to learn from one of these realities some information which would normally be hidden from him. -

Elder Futhark Rune Poem and Some Notes RYKHART: ODINSXRAL

Elder Futhark Rune Poem and some notes RYKHART: ODINSXRAL Dedication Mysteries ancient, Allfather found Wrested from anguish, nine days fast bound Hung from the world tree, pierced by the spear Odin who seized them, make these staves clear 1 Unless otherwise specified, all text and artwork within ELDER FUTHARK RUNE POEM and some notes RYKHART: ODINSXRAL are copyright by the author and is not to be copied or reproduced in any medium or form without the express written permission of the author Reikhart Odinsthrall both Reikhart Odinsthrall and RYKHART: ODINSXRAL are also both copyright Dec 31, 2013 Elder Futhark Rune Poem by Reikhart Odinsthrall is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Based on a work at http://odinsthrall.co.uk/rune-poem.html. 2 F: Fehu : Cattle / Wealth Wealth is won and gold bestowed But honour's due to all men owed Gift the given and ware the lord For thy name's worth noised abroad U: Uruz : Aurochs / Wild-ox Wild ox-blood proud, sharp hornéd might On moorland harsh midst sprite and wight Unconquered will and fierce in form Through summer's sun and winter's storm X: Thurisaz : Thorn / Giant / Thor Thorn hedge bound the foe repelled A giant's anger by Mjolnir felled Thor protect us, fight for troth In anger true as Odin's wrath A: Ansuz : As / God / Odin In mead divine and written word In raven's call and whisper heard Wisdom seek and wise-way act In Mimir's well see Odin's pact R: Raidho : Journey / Carriage By horse and wheel to travel far Till journey's -

The Correspondence of Just Qvigstad, 1.0 and 2.0 – the Ongoing Story of a Digital Edition

The correspondence of Just Qvigstad, 1.0 and 2.0 – the ongoing story of a digital edition UiT Digital Humanities Conference Tromsø, 30 November – 1 December 2017 Øyvind Eide, University of Cologne, Germany Per P. Aspaas & Philipp Conzett, UiT The Arctic University of Norway Outline • Just Qvigstad • Qvigstad’s correspondence 1.0 – Documentation Project in the 1990s • Qvigstad’s correspondence 2.0 – digital edition(s) project • The role of university libraries in digital edition/humanities projects Just Knud Qvigstad Born 4th of April 1853 in Lyngseidet, near Tromsø Died 15th of March 1957 in Tromsø Norwegian philologist, linguist, ethnographer, historian and cultural historian Headmaster at Tromsø Teacher Training College (= one of UiTs “predecessors”) Expert on Sami language and culture (“lappologist”) (Photo: Wikimedia Commons – S. Blom (ed.): Extensive correspondence with other experts Den Kongelige Norske St. Olavs Orden, A. M. on Sami Hanches Forlag, 1934) The Documentation Project “From Drawer to Screen” Nationwide digitisation project aiming at transferring the various university collections from paper to computers Started in 1991 at the University of Oslo. Bergen, Trondheim and Tromsø joined in 1992 Range of disciplines: archaeology, ethnography, history, lexicography, folklore studies, literature, medieval studies, place names, coins/numismatics Qvigstad’s correspondence 1.0 Qvigstad to Magnus Olsen 1909-1956 (65 letters). National Library of Norway. Qvigstad to K. B. Wiklund 1891-1936 (96 letters). Uppsala University Library. Qvigstad til Emil N. Setälä 1887-1935 (96 letters). National Archives of Finland, prof. Setälä’s private archive. http://www.dokpro.uio.no/perl/historie/ qvigstadtxt.cgi?hand=Ja&id=setele066&fr http://www.dokpro.uio.no/qvigstad/setele-faks/set004.jpg ames=Nei Qvigstad’s correspondence 1.0 20 years have passed .. -

Reading Cult and Mythology in Society and Landscape: the Toponymic Evidence

Reading Cult and Mythology in Society and Landscape: The Toponymic Evidence Stefan Brink Across all cultures, myths have been used to explain phenomena and events beyond people’s comprehension. Our focus in research on Scandinavian mythology has, to a large extent, been to describe, uncover, and critically assess these myths, examining the characteristics and acts not only of gods and goddesses, but also of the minor deities found in the poems, sagas, Snorra Edda, and Saxo. All this research is and has been conducted to fathom, as far as possible, the cosmology, the cosmogony, and eschatology—in short, the mythology—of pagan Scandinavia. An early branch of scholarship focused on extracting knowledge of this kind from later collections of folklore. This approach was heavily criticized and placed in the poison cabinet for decades, but seems to have come back into fashion, brought once again into the light by younger scholars who are possibly unaware of the total dismissal of the approach in the 1920s and 30s. Another productive area of the research has been the examination of the cults and rituals among pre-Christian Scandinavians as described and indicated by written sources, iconography, archaeology, and toponymy. When preparing for this paper I planned to do two things: First, to paint, with broad strokes, the toponymic research history of the study of sacral and cultic place names. The goal here is to provide a broad picture of the current state of research in this field, hopefully revealing how toponymists work and think today. Second, I aimed to look at the myths not descriptively—retelling and analyzing the stories in the written sources—but rather instrumentally. -

Pursuing West: the Viking Expeditions of North America

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2015 Pursuing West: The iV king Expeditions of North America Jody M. Bryant East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Jody M., "Pursuing West: The iV king Expeditions of North America" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2508. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2508 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pursuing West: The Viking Expeditions of North America _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History _____________________ by Jody Melinda Bryant May 2015 _____________________ Dr. William Douglas Burgess, Jr., Chair Dr. Henry J. Antkiewicz Dr. John M. Rankin Keywords: Kensington Rune Stone, Runes, Vikings, Gotland ABSTRACT Pursuing West: The Viking Expeditions of North America by Jody Bryant The purpose to this thesis is to demonstrate the activity of the Viking presence, in North America. The research focuses on the use of stones, carved with runic inscriptions that have been discovered in Okla- homa, Maine, Rhode Island and Minnesota. The thesis discusses orthographic traits found in the in- scriptions and gives evidence that links their primary use to fourteenth century Gotland.