A Runic Inscription from Baconsthorpe, Norfolk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beer Shop Beer Shop

1 3 10 11 13 14 West Norfolk C5 E3 C4 C3 Sandringham House C2 C3 VISIT BRITAIN’S BIGGEST BEER SHOP & What To Do 2016 Plus WINE AND SPIRIT WWAREHOUSEAREHOUSE Sandringham House, the Royal Family’s country retreat, ATTRACTIONS is perhaps the most famous stately home in Norfolk - and certainly one of the most beautiful. The Coffee Shop at Thaxters Garden Centre is PLACES TO VISIT Opens Easter 2016 Set in 60 acres of stunning gardens, with a fascinating renowned locally for its own home-made cakes museum of Royal vehicles and mementos, the principal and scones baked daily. Its menu ranges from the EVENTS ground floor apartments with their charming collections popular cooked breakfast to sandwiches, baguettes YOUYOU DON’TDON’T HAVEHAVE Visit King’s Lynn’s of porcelain, jade, furniture and family portraits are open throughout West Norfolk and our homemade specials of the day. During the stunning new to the public. Visitor Centre open every day all year. warmer months there is an attractive garden when TOTO TRAVELTRAVEL THETHE attraction, which Open daily 26 March- 30 October you can sit and enjoy lunch and coffee. EXCEPT Wednesday 27 July. tells the stories of the Take a stroll around the attractive Garden Centre. Adults £14.00, Seniors £12.50, Children £7.00 GLOBEGLOBE TOTO ENJOYENJOY seafarers, explorers, Family (2 adults + 3 children) £35.00 It sells everything the garden could need as well as merchants, mayors, www.sandringhamestate.co.uk a large range of giftware. WORLDWORLD BEERS.BEERS.BEERS. magistrates and If you are staying in self-catering accommodation 4 North Brink, Wisbech, PE13 1LW 12 or a caravan there is a well stocked grocery store Tel: 01945 583160 miscreants who have A5 www.elgoods-brewery.co.uk C4 on site that sells hot chickens from its rotisserie, It is just a short haul to shaped King’s Lynn, one of freshly baked bread, newspapers, lottery and England’s most important everything you could possibly need. -

Parish Share Report

PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS For period ended 30th September 2019 SUMMARY OF PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS BY DEANERIES Dean Amount % Deanery Share Received for 2019 % Deanery Share % No Outstanding 2018 2019 to period end 2018 Received for 2018 received £ £ £ £ £ Norwich Archdeaconry 06 Norwich East 23,500 4.41 557,186 354,184 63.57 532,380 322,654 60.61 04 Norwich North 47,317 9.36 508,577 333,671 65.61 505,697 335,854 66.41 05 Norwich South 28,950 7.21 409,212 267,621 65.40 401,270 276,984 69.03 Norfolk Archdeaconry 01 Blofield 37,303 11.04 327,284 212,276 64.86 338,033 227,711 67.36 11 Depwade 46,736 16.20 280,831 137,847 49.09 288,484 155,218 53.80 02 Great Yarmouth 44,786 9.37 467,972 283,804 60.65 478,063 278,114 58.18 13 Humbleyard 47,747 11.00 437,949 192,301 43.91 433,952 205,085 47.26 14 Loddon 62,404 19.34 335,571 165,520 49.32 322,731 174,229 53.99 15 Lothingland 21,237 3.90 562,194 381,997 67.95 545,102 401,890 73.73 16 Redenhall 55,930 17.17 339,813 183,032 53.86 325,740 187,989 57.71 09 St Benet 36,663 9.24 380,642 229,484 60.29 396,955 243,433 61.33 17 Thetford & Rockland 31,271 10.39 314,266 182,806 58.17 300,933 192,966 64.12 Lynn Archdeaconry 18 Breckland 45,799 11.97 397,811 233,505 58.70 382,462 239,714 62.68 20 Burnham & Walsingham 63,028 15.65 396,393 241,163 60.84 402,850 256,123 63.58 12 Dereham in Mitford 43,605 12.03 353,955 223,631 63.18 362,376 208,125 57.43 21 Heacham & Rising 24,243 6.74 377,375 245,242 64.99 359,790 242,156 67.30 22 Holt 28,275 8.55 327,646 207,089 63.21 330,766 214,952 64.99 23 Lynn 10,805 3.30 330,152 196,022 59.37 326,964 187,510 57.35 07 Repps 0 0.00 383,729 278,123 72.48 382,728 285,790 74.67 03 08 Ingworth & Sparham 27,983 6.66 425,260 239,965 56.43 420,215 258,960 61.63 727,583 9.28 7,913,818 4,789,282 60.52 7,837,491 4,895,456 62.46 01/10/2019 NORWICH DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE LTD DEANERY HISTORY REPORT MONTH September YEAR 2019 SUMMARY PARISH 2017 OUTST. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List Of

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List of 1471412 It 44 Norfolk Census 1851 Index 6115160 Norfolk Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It 1 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1811-1825 375230 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1825-1839 375231 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1839-1859 375232 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1715-1734 1596461 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1734-1749 1596462 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1770-1774 1596563 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1774-1781 1596564 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1790-1797 1596566 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1798-1803 1596567 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1812-1819 1596597 Norfolk Marriages Parish Registers 1539-1812 496683 It 2 Norfolk Probate Inventories Index 1674-1825 1471414 It 17-20 Norfolk Tax Assessments 1692-1806 1471412 It 30-43 Norfolk Wills V.101 1854-1857 167184 Norfolk Alburgh Parish Register Extracts 1538-1715 894712 It 5 Norfolk Alby Parish Records 1600-1812 1526778 It 15 Norfolk Aldeby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 6 Norfolk Alethorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Arminghall Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Ashby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 7 Norfolk Ashby Parish Register Extracts 1646 894712 It 5 Norfolk Ashwell-Thorpe Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Aslacton Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Baconsthorpe Parish Register Extracts 1676-1770 894712 It 6 Norfolk Bagthorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Bale Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Bale Parish Register Extracts 1538-1716 894712 It 6 Norfolk Barmer Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barney Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barton-Bendish Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It -

River Glaven State of the Environment Report

The River Glaven A State of the Environment Report ©Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative ©Evelyn Simak and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence Commons Licence © Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative ©Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence Commons Licence Produced by Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service Spring 2014 i Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service (NBIS) is a Local Record Centre holding information on species, GEODIVERSITY, habitats and protected sites for the county of Norfolk. For more information see our website: www.nbis.org.uk This report is available for download from the NBIS website www.nbis.org.uk Report written by Lizzy Oddy, March 2014. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank the following people for their help and input into this report: Mark Andrews (Environment Agency); Anj Beckham (Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service); Andrew Cannon (Natural Surroundings); Claire Humphries (Environment Agency); Tim Jacklin (Wild Trout Trust); Kelly Powell (Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service); Carl Sayer (University College London); Ian Shepherd (River Glaven Conservation Group); Mike Sutton-Croft (Norfolk Non-native Species Initiative); Jonah Tosney (Norfolk Rivers Trust) Cover Photos Clockwise from top left: Wiveton Bridge (©Evelyn Simak and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); Glandford Ford (©Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); River Glaven above Glandford (©Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); Swan at Glandford Ford (© Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence). ii CONTENTS Foreword – Gemma Clark, 9 Chalk Rivers Project Community Involvement Officer.….…………………… v Welcome ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Landscape History & GEODIVERSITY ………………………..…………………………………………………………………. -

North Norfolk District Council (Alby

DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT VOLUME I PARISH OF ALBY WITH THWAITE Footpath No. 1 (Middle Hill to Aldborough Mill). Starts from Middle Hill and runs north westwards to Aldborough Hill at parish boundary where it joins Footpath No. 12 of Aldborough. Footpath No. 2 (Alby Hill to All Saints' Church). Starts from Alby Hill and runs southwards to enter road opposite All Saints' Church. Footpath No. 3 (Dovehouse Lane to Footpath 13). Starts from Alby Hill and runs northwards, then turning eastwards, crosses Footpath No. 5 then again northwards, and continuing north-eastwards to field gate. Path continues from field gate in a south- easterly direction crossing the end Footpath No. 4 and U14440 continuing until it meets Footpath No.13 at TG 20567/34065. Footpath No. 4 (Park Farm to Sunday School). Starts from Park Farm and runs south westwards to Footpath No. 3 and U14440. Footpath No. 5 (Pack Lane). Starts from the C288 at TG 20237/33581 going in a northerly direction parallel and to the eastern boundary of the cemetery for a distance of approximately 11 metres to TG 20236/33589. Continuing in a westerly direction following the existing path for approximately 34 metres to TG 20201/33589 at the western boundary of the cemetery. Continuing in a generally northerly direction parallel to the western boundary of the cemetery for approximately 23 metres to the field boundary at TG 20206/33611. Continuing in a westerly direction parallel to and to the northern side of the field boundary for a distance of approximately 153 metres to exit onto the U440 road at TG 20054/33633. -

The Owners of Baconsthorpe Castle

The Owners of Baconsthorpe Castle John Heydon (died 1410 – 1480) Married Eleanor Lomax Was a lawyer and JP. Started construction of Baconsthorpe Castle in 1475. Sir Henry Heydon (died 1503) Married Anne Boleyn (the great aunt of Queen Anne Boleyn) Was a Lawyer and JP and accumulated great wealth and lands. Finished construction of Baconsthorpe Castle in 1486. Built Salthouse Church, finished in 1503. Sir John Heydon (1468 – 1550) Married Catherine Willoughby Attended King Henry VIII Sir Christopher Heydon I (1495 – 1541) Married Ann Heveningham. Died before his father. Sir Christopher Heydon II (1517 – 1579) Married 1. Lady Ann Drury (she is the Lady Ann Heydon in the brass in Baconsthorpe church). 2. Dame Temperance Carewe 3. Agnes Was a magistrate and MP. He is said to have entertained thirty head, or master shepherds of his own flocks at a Christmas dinner at Baconsthorpe. He is buried in the south aisle of Baconsthorpe church Sir William Heydon (1540 – 1594) Married Lady Anne Woodhouse. Was a JP. The alabaster Heydon memorial in Baconsthorpe church is for William and Anne. William had to sell land at Baconsthorpe to pay debts. Sir Christopher Heydon III (1561 – 1623) Married 1. Mirabel Kivet – buried in Saxlingham church 2. Ann Dodge – buried in Baconsthorpe church Was a scholar Christopher openly rebelled against Elizabeth I in 1600 and was arrested, imprisoned and had all his houses, goods and chattel’s seized. He was released from prison in 1602 and fined £2000.00 which resulted in his financial collapse. Christopher is buried in Baconsthorpe Church. Sir William Heydon II (died 1627) Died in battle at the invasion of the Isle of Rhe in France. -

The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia and the Origins and Distribution of Common Fields*

The Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia and the origins and distribution of common fields* by Susan Oosthuizen Abstract: This paper aims to explore the hypothesis that the agricultural layouts and organisation that had de- veloped into common fields by the high middle ages may have had their origins in the ‘long’ eighth century, between about 670 and 840 AD. It begins by reiterating the distinction between medieval open and common fields, and the problems that inhibit current explanations for their period of origin and distribution. The distribution of common fields is reviewed and the coincidence with the kingdom of Mercia noted. Evidence pointing towards an earlier date for the origin of fields is reviewed. Current views of Mercia in the ‘long’ eighth century are discussed and it is shown that the kingdom had both the cultural and economic vitality to implement far-reaching landscape organisation. The proposition that early forms of these field systems may have originated in the ‘long’ eighth century is considered, and the paper concludes with suggestions for further research. Open and common fields (a specialised form of open field) endured in the English landscape for over a thousand years and their physical remains still survive in many places. A great deal is known and understood about their distribution and physical appearance, about their man- agement from their peak in the thirteenth century through the changes of the later medieval and early modern periods, and about how and when they disappeared. Their origins, however, present a continuing problem partly, at least, because of the difficulties in extrapolating in- formation about such beginnings from documentary sources and upstanding earthworks that record – or fossilise – mature or even late field systems. -

Viking-Age Runic Plates of the Runic Plates Have Been Conducted with a Stereomicroscope for This Purpose

The aim of this dissertation is to represent as clearly as possible the genre of Viking- Age runic plates by developing readings and interpretations of the inscriptions on the 46 metal plates with runes from the Viking Age known today. Several investigations SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH • • PERESWETOFF-MORATH SOFIA Viking-Age Runic Plates of the runic plates have been conducted with a stereomicroscope for this purpose. On the basis of the new readings thus established, new interpretations have been pro- posed for the most problematic sections of previously interpreted inscriptions. New interpretations are also offered for inscriptions on runic plates which have previously been considered non-lexical. As well as providing new readings and interpretations, this study has resulted in clarification of the relationship between the form and content of the inscriptions on the runic plates on the one hand and on their find circumstances and appearance on the other. An argued documentation of the readings can be found in an accompanying catalogue in Swedish which is published digitally and can be downloaded as a pdf file at: <http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-383584> Viking-Age Runic Plates Viking-Age Distribution: Sofia Pereswetoff-Morath eddy.se ab e-post: [email protected] ISSN 0065-0897 and Box 1310, 621 24 Visby. Telefon: 0498-25 39 00 ISSN 1100-1690 http://kgaa.bokorder.se ISBN 978-91-87403-33-0 1 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI 155 Runrön 21 Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 2 3 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI CLV Runrön 21 Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH Viking-Age Runic Plates Readings and Interpretations Translated from Swedish by Mindy MacLeod UPPSALA 2019 Kungl. -

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

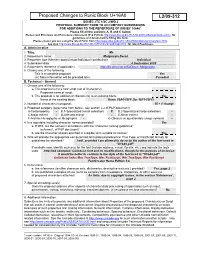

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4. -

THE NINE DOORS of MIDGARD a Curriculum of Rune-Work

,. , - " , , • • • • THE NINE DOORS OF MmGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work - • '. Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin·Drighten of the Rune-Gild THE NINE DOORS OF MIDGARD A Curriculum of Rune-Work Second Revised Edition EDRED Yrmin-Drighten of the Rune-Gild 1997 - Introduction This work is the first systematic introduction to Runelore available in many centuries. This age requires and allows some new approaches to be sure. We have changed over the centuries in question. But at the same time we are as traditional as possible. The Gild does not fear innovation - in fact we embrace it - but only after the tradition has been thoroughly examined for all it has to offer. Too often in the history of the runic revival various proponents have actually taken their preconceived notions about what the Runes should say- and then "runicized" them. We avoid this type of pseudo-innovation at all costs. Our over-all magical method is a simple one. The tradition posits an outer world (objective reality) and an inner-world (subjective reality). The work of the Runer is the exploration of both of these worlds for what they have to offer in the search for wisdom. In learning the Runes, the Runer synthesizes all the objective lore and tradition he can find on the Runes with his subjective experience. In this way he "makes the Runes his own." All the Runes and their overall system are then used as a sort of "meta-Ianguage" in meaningful communication between these objective and subjective realities. The Runer may wish to be active in this communication - to cause changes to occur in accordance with his will, or he may wish to learn from one of these realities some information which would normally be hidden from him. -

The Coinage of Southern England, 796-840

THE COINAGE OF SOUTHERN ENGLAND, 796-840 C. E. BLUNT, C. S. S. LYON, and B. H. I. H. STEWART INTRODUCTORY WE think it desirable to explain how this paper came to be written under our joint names. For some years we have independently been aware of the shortcomings of the accepted chronology and classification of the coinage of the southern kingdoms in the age of the decline of the power of Mercia following the death of Offa. One of us, too, has been unhappy at the doubt which has been cast on the authenticity of certain coins in the Mercian series. Research in both these fields led us to write papers, read before the Society in successive years,1 that not only overlapped to an appreciable extent but which happily showed a very broad measure of agreement on the interpretation of the surviving material. We therefore felt that a single definitive publication, resulting from the integra- tion of our separate researches, would be more valuable than two distinct papers, and this we now offer. Brooke classified the ninth-century coinage according to the kingdom from which a named ruler derived his primary authority. While this may be a satisfactory basis for the coinages of the kings of Kent and of East Anglia, whose mints were, of necessity, located within their own immediate territories, it is quite unsuitable for the issues of the kings of Mercia, who were at times in a position to employ these same mints to strike the bulk of their own coinage. This is also true to a lesser extent, at a later stage, of the coins of the kings of Wessex.