Early Germanic Literature and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT Savannah Dehart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF

ABSTRACT Savannah DeHart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF NORTHERN PAGAN RELIGIOSITY IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES. (Under the direction of Michael J. Enright) Department of History, May 2012. This thesis investigates the religiosity of some Germanic peoples of the Migration period (approximately AD 300-800) and seeks to overcome some difficulties in the related source material. The written sources which describe pagan elements of this period - such as Tacitus’ Germania, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards - are problematic because they were composed by Roman or Christian authors whose primary goals were not to preserve the traditions of pagans. Literary sources of the High Middle Ages (approximately AD 1000-1400) - such as The Poetic Edda, Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda , and Icelandic Family Sagas - can only offer a clearer picture of Old Norse religiosity alone. The problem is that the beliefs described by these late sources cannot accurately reflect religious conditions of the Early Middle Ages. Too much time has elapsed and too many changes have occurred. If literary sources are unavailing, however, archaeology can offer a way out of the dilemma. Rightly interpreted, archaeological evidence can be used in conjunction with literary sources to demonstrate considerable continuity in precisely this area of religiosity. Some of the most relevant material objects (often overlooked by scholars) are bracteates. These coin-like amulets are stamped with designs that appear to reflect motifs from Old Norse myths, yet their find contexts, including the inhumation graves of women and hoards, demonstrate that they were used during the Migration period of half a millennium earlier. -

Hunnic Warfare in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries C.E.: Archery and the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire

HUNNIC WARFARE IN THE FOURTH AND FIFTH CENTURIES C.E.: ARCHERY AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE WESTERN ROMAN EMPIRE A Thesis Submitted to the Committee of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Laura E. Fyfe 2016 Anthropology M.A. Graduate Program January 2017 ABSTRACT Hunnic Warfare in the Fourth and Fifth Centuries C.E.: Archery and the Collapse of the Western Roman Empire Laura E. Fyfe The Huns are one of the most misunderstood and mythologized barbarian invaders encountered by the Roman Empire. They were described by their contemporaries as savage nomadic warriors with superior archery skills, and it is this image that has been written into the history of the fall of the Western Roman Empire and influenced studies of Late Antiquity through countless generations of scholarship. This study examines evidence of Hunnic archery, questions the acceptance and significance of the “Hunnic archer” image, and situates Hunnic archery within the context of the fall of the Western Roman Empire. To achieve a more accurate picture of the importance of archery in Hunnic warfare and society, this study undertakes a mortuary analysis of burial sites associated with the Huns in Europe, a tactical and logistical study of mounted archery and Late Roman and Hunnic military engagements, and an analysis of the primary and secondary literature. Keywords: Archer, Archery, Army, Arrow, Barbarian, Bow, Burial Assemblages, Byzantine, Collapse, Composite Bow, Frontier, Hun, Logistics, Migration Period, Roman, Roman Empire, Tactics, Weapons Graves ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. -

Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and Natural History

Proceedingsof the SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND NATURAL HISTORY 4 °4vv.es`Egi vI V°BkIAS VOLUME XXV, PART 1 (published 1950) PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY W. E. HARRISON & SONS, LTD., THE ANCIENT HOUSE, IPSWI611. The costof publishing this paper has beenpartially defrayedby a Grant from the Council for British Archeology. THE SUTTON HOO SHIP-BURIAL Recenttheoriesand somecommentsongeneralinterpretation By R. L. S. BRUCE-MITFORD, SEC. S.A. INTRODUCTION The Sutton Hoo ship-burial was discovered more than ten years ago. During these years especially since the end of the war in Europe has made it possible to continue the treatment and study of the finds and proceed with comparative research, its deep significance for general and art history, Old English literature and European archmology has become more and more evident. Yet much uncertainty prevails on general issues. Many questions cannot receive their final answer until the remaining mounds of the grave-field have been excavated. Others can be answered, or at any rate clarified, now. The purpose of this article is to clarify the broad position of the burial in English history and archmology. For example, it has been said that ' practically the whole of the Sutton Hoo ship-treasure is an importation from the Uppland province of Sweden. The great bulk of the work was produced in Sweden itself.' 1 Another writer claims that the Sutton Hoo ship- burial is the grave of a Swedish chief or king.' Clearly we must establish whether it is part of English archxology, or of Swedish, before we can start to draw from it the implications that we are impatient to draw. -

University of London Deviant Burials in Viking-Age

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA Ruth Lydia Taylor M. Phil, Institute of Archaeology, University College London UMI Number: U602472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602472 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT DEVIANT BURIALS IN VIKING-AGE SCANDINAVIA The thesis brings together information yielded from archaeology and other sources to provide an overall picture of the types of burial practices encountered during the Viking-Age in Scandinavia. From this, an attempt is made to establish deviancy. Comparative evidence, such as literary, runic, legal and folkloric evidence will be used critically to shed perspective on burial practices and the artefacts found within the graves. The thesis will mostly cover burials from the Viking Age (late 8th century to the mid- 11th century), but where the comparative evidence dates from other periods, its validity is discussed accordingly. Two types of deviant burial emerged: the criminal and the victim. A third type, which shows distinctive irregularity yet lacks deviancy, is the healer/witch burial. -

Sniðmát Meistaraverkefnis HÍ

MA ritgerð Norræn trú Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell Október 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell 60 einingar Félags– og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Október, 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA-gráðu í Norrænni trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Caroline Elizabeth Oxley, 2019 Prentun: Háskólaprent Reykjavík, Ísland, 2019 Caroline Oxley MA in Old Nordic Religion: Thesis Kennitala: 181291-3899 Október 2019 Abstract Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum: Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view This thesis is a study of animal shape-shifting in Old Norse culture, considering, among other things, the related concepts of hamr, hugr, and the fylgjur (and variations on these concepts) as well as how shape-shifters appear to be associated with the wild, exile, immorality, and violence. Whether human, deities, or some other type of species, the shape-shifter can be categorized as an ambiguous and fluid figure who breaks down many typical societal borderlines including those relating to gender, biology, animal/ human, and sexual orientation. As a whole, this research project seeks to better understand the background, nature, and identity of these figures, in part by approaching the subject psychoanalytically, more specifically within the framework established by the Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, as part of his theory of archetypes. -

5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721

Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) P. Faltstrom, Ed. Request for Comments: 5892 Cisco Category: Standards Track August 2010 ISSN: 2070-1721 The Unicode Code Points and Internationalized Domain Names for Applications (IDNA) Abstract This document specifies rules for deciding whether a code point, considered in isolation or in context, is a candidate for inclusion in an Internationalized Domain Name (IDN). It is part of the specification of Internationalizing Domain Names in Applications 2008 (IDNA2008). Status of This Memo This is an Internet Standards Track document. This document is a product of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It represents the consensus of the IETF community. It has received public review and has been approved for publication by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG). Further information on Internet Standards is available in Section 2 of RFC 5741. Information about the current status of this document, any errata, and how to provide feedback on it may be obtained at http://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc5892. Copyright Notice Copyright (c) 2010 IETF Trust and the persons identified as the document authors. All rights reserved. This document is subject to BCP 78 and the IETF Trust's Legal Provisions Relating to IETF Documents (http://trustee.ietf.org/license-info) in effect on the date of publication of this document. Please review these documents carefully, as they describe your rights and restrictions with respect to this document. Code Components extracted from this document must include Simplified BSD License text as described in Section 4.e of the Trust Legal Provisions and are provided without warranty as described in the Simplified BSD License. -

Nancy L. Wicker and Henrik Williams. Futhark 3

Futhark International Journal of Runic Studies Main editors James E. Knirk and Henrik Williams Assistant editor Marco Bianchi Vol. 3 · 2012 © Contributing authors 2013 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ All articles are available free of charge at http://www.futhark-journal.com A printed version of the issue can be ordered through http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-194111 Editorial advisory board: Michael P. Barnes (University College London), Klaus Düwel (University of Göttingen), Lena Peterson (Uppsala University), Marie Stoklund (National Museum, Copenhagen) Typeset with Linux Libertine by Marco Bianchi University of Oslo Uppsala University ISSN 1892-0950 Bracteates and Runes Review article by Nancy L. Wicker and Henrik Williams Die Goldbrakteaten der Völkerwanderungszeit — Auswertung und Neufunde. Eds. Wilhelm Heizmann and Morten Axboe. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 40. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2011. 1024 pp., 102 plates. ISBN 978-3-11-022411-5, e-ISBN 978-3-11-022411-2, ISSN 1866-7678. 199.95 €, $280. From the Migration Period we now have more than a thousand stamped gold pendants known as bracteates. They have fascinated scholars since the late seventeenth century and continue to do so today. Although bracteates are fundamental sources for the art history of the period, and important archae- o logical artifacts, for runologists their inscriptions have played a minor role in comparison with other older-futhark texts. It is to be hoped that this will now change, however. -

Context Analysis and Bracteate Inscriptions in Light of Alternative Iconographic Interpretations

Context analysis and bracteate inscriptions in light of alternative iconographic interpretations Nancy L. Wicker Although nearly 1000 Scandinavian Migration Period (fifth- and sixth-century) gold pendants called bracteates have been discovered in Scandinavia and throughout northern and central Europe, only about twenty percent of these objects have inscriptions. The writing is mostly in the elder futhark but also in corrupted Latin copied from inscriptions on Late Roman coins and medallions, which are presumably the models for bracteate imagery. Relatively few of the 170 bracteates with runic inscriptions—which are known from only 110 different dies (Düwel 2008: 46)—are semantically meaningful. While the research of the late Karl Hauck has dominated bracteate scholarship for the past forty years, his theory of bracteate iconography is not the only possible interpretation of this imagery that may illuminate our understanding of the inscriptions. In this paper, I will high- light other interpretations of bracteates, not as definitive answers to the meaning of bracteates but instead to emphasize the tenuous nature of all such theories. I also propose the use of what Michaela Helmbrecht (2008) has termed ‗context analysis‘ to focus on the various contexts in which bracteates have been discovered in order to shed additional light upon their meaning. Before presenting alternate explanations, I will review basic information about bracteates and their inscriptions, and I will summarize the basic tenets of Hauck‘s thesis. Bracteate classification and iconography From the earliest research on bracteates, scholars including C. J. Thomsen (1855), Oscar Montelius (1869), and Bernhard Salin (1895) focused on organizing these artifacts by classi- fying them into types according to details of images depicted in the central stamped field of decoration. -

MUFI Character Recommendation V. 3.0: Alphabetical Order

MUFI character recommendation Characters in the official Unicode Standard and in the Private Use Area for Medieval texts written in the Latin alphabet ⁋ ※ ð ƿ ᵹ ᴆ ※ ¶ ※ Part 1: Alphabetical order ※ Version 3.0 (5 July 2009) ※ Compliant with the Unicode Standard version 5.1 ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ※ Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (MUFI) ※ www.mufi.info ISBN 978-82-8088-402-2 ※ Characters on shaded background belong to the Private Use Area. Please read the introduction p. 11 carefully before using any of these characters. MUFI character recommendation ※ Part 1: alphabetical order version 3.0 p. 2 / 165 Editor Odd Einar Haugen, University of Bergen, Norway. Background Version 1.0 of the MUFI recommendation was published electronically and in hard copy on 8 December 2003. It was the result of an almost two-year-long electronic discussion within the Medieval Unicode Font Initiative (http://www.mufi.info), which was established in July 2001 at the International Medi- eval Congress in Leeds. Version 1.0 contained a total of 828 characters, of which 473 characters were selected from various charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 355 were located in the Private Use Area. Version 1.0 of the recommendation is compliant with the Unicode Standard version 4.0. Version 2.0 is a major update, published electronically on 22 December 2006. It contains a few corrections of misprints in version 1.0 and 516 additional char- acters (of which 123 are from charts in the official part of the Unicode Standard and 393 are additions to the Private Use Area). -

Viking-Age Runic Plates of the Runic Plates Have Been Conducted with a Stereomicroscope for This Purpose

The aim of this dissertation is to represent as clearly as possible the genre of Viking- Age runic plates by developing readings and interpretations of the inscriptions on the 46 metal plates with runes from the Viking Age known today. Several investigations SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH • • PERESWETOFF-MORATH SOFIA Viking-Age Runic Plates of the runic plates have been conducted with a stereomicroscope for this purpose. On the basis of the new readings thus established, new interpretations have been pro- posed for the most problematic sections of previously interpreted inscriptions. New interpretations are also offered for inscriptions on runic plates which have previously been considered non-lexical. As well as providing new readings and interpretations, this study has resulted in clarification of the relationship between the form and content of the inscriptions on the runic plates on the one hand and on their find circumstances and appearance on the other. An argued documentation of the readings can be found in an accompanying catalogue in Swedish which is published digitally and can be downloaded as a pdf file at: <http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-383584> Viking-Age Runic Plates Viking-Age Distribution: Sofia Pereswetoff-Morath eddy.se ab e-post: [email protected] ISSN 0065-0897 and Box 1310, 621 24 Visby. Telefon: 0498-25 39 00 ISSN 1100-1690 http://kgaa.bokorder.se ISBN 978-91-87403-33-0 1 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI 155 Runrön 21 Runrön Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet 2 3 ACTA ACADEMIAE REGIAE GUSTAVI ADOLPHI CLV Runrön 21 Runologiska bidrag utgivna av Institutionen för nordiska språk vid Uppsala universitet SOFIA PERESWETOFF-MORATH Viking-Age Runic Plates Readings and Interpretations Translated from Swedish by Mindy MacLeod UPPSALA 2019 Kungl. -

Anglo-Saxon Runes

Runes Each rune can mean something in divination (fortune telling) but they also act as a phonetic alphabet. This means that they can sound out words. When writing your name or whatever in runes, don’t pay attention to the letters we use, but rather the sounds we use to make up the words. Then finds the runes with the closest sounds and put them together. Anglo- Swedo- Roman Germanic Danish Saxon Norwegian A ansuz ac ar or god oak-tree (?) AE aesch ash-tree A/O or B berkanan bercon or birch-twig (?) C cen torch D dagaz day E ehwaz horse EA ear earth, grave(?) F fehu feoh fe fe money, cattle, money, money, money, wealth property property property gyfu / G gebo geofu gift gift (?) G gar spear H hagalaz hail hagol (?) I isa is iss ice ice ice Ï The sound of this character was something ihwaz / close to, but not exactly eihwaz like I or IE. yew-tree J jera year, fruitful part of the year K kenaz calc torch, flame (?) (?) K name unknown L laguz / laukaz water / fertility M mannaz man N naudiz need, necessity, nou (?) extremity ing NG ingwaz the god the god "Ing" "Ing" O othala- hereditary land, oethil possession OE P perth-(?) peorth meaning unclear (?) R raidho reth (?) riding, carriage S sowilo sun or sol (?) or sun tiwaz / teiwaz T the god Tiw (whose name survives in Tyr "Tuesday") TH thurisaz thorn thurs giant, monster (?) thorn giant, monster U uruz ur wild ox (?) wild ox W wunjo joy X Y yr bow (?) Z agiz(?) meaning unclear Now write your name: _________________________________________________________________ Rune table borrowed from: www.cratchit.org/dleigh/alpha/runes/runes.htm . -

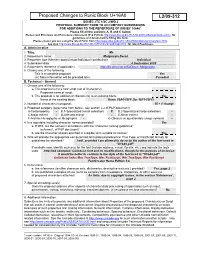

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4.