Getting to Know You: Profiles of Children's Authors Featured in "Language Arts" 1985-90

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Building Cold War Warriors: Socialization of the Final Cold War Generation

BUILDING COLD WAR WARRIORS: SOCIALIZATION OF THE FINAL COLD WAR GENERATION Steven Robert Bellavia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Andrew M. Schocket, Advisor Karen B. Guzzo Graduate Faculty Representative Benjamin P. Greene Rebecca J. Mancuso © 2018 Steven Robert Bellavia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This dissertation examines the experiences of the final Cold War generation. I define this cohort as a subset of Generation X born between 1965 and 1971. The primary focus of this dissertation is to study the ways this cohort interacted with the three messages found embedded within the Cold War us vs. them binary. These messages included an emphasis on American exceptionalism, a manufactured and heightened fear of World War III, as well as the othering of the Soviet Union and its people. I begin the dissertation in the 1970s, - during the period of détente- where I examine the cohort’s experiences in elementary school. There they learned who was important within the American mythos and the rituals associated with being an American. This is followed by an examination of 1976’s bicentennial celebration, which focuses on not only the planning for the celebration but also specific events designed to fulfill the two prime directives of the celebration. As the 1980s came around not only did the Cold War change but also the cohort entered high school. Within this stage of this cohorts education, where I focus on the textbooks used by the cohort and the ways these textbooks reinforced notions of patriotism and being an American citizen. -

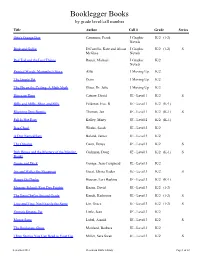

Booklegger Books by Grade Level/Call Number

Booklegger Books by grade level/call number Title Author Call # Grade Series Otto's Orange Day Cammuso, Frank J Graphic K/2 (1-2) Novels Bink and Gollie DiCamillo, Kate and Alison J Graphic K/2 (1-2) S McGhee Novels Red Ted and the Lost Things Rosen, Michael J Graphic K/2 Novels Painted Words: Marianthe's Story Aliki J Moving Up K/2 The Empty Pot Demi J Moving Up K/2 The Fly on the Ceiling: A Math Myth Glass, Dr. Julie J Moving Up K/2 Dinosaur Hunt Catrow, David JE - Level 1 K/2 S Billy and Milly, Short and Silly Feldman, Eve. B JE - Level 1 K/2 (K-1) Rhyming Dust Bunnie Thomas, Jan JE - Level 1 K/2 (K-1) S Fall Is Not Easy Kelley, Marty JE - Level 2 K/2 (K-1) Baa-Choo! Weeks, Sarah JE - Level 2 K/2 A Dog Named Sam Boland, Janice JE - Level 3 K/2 The Octopus Cazet, Denys JE - Level 3 K/2 S Dirk Bones and the Mystery of the Missing Cushman, Doug JE - Level 3 K/2 (K-1) S Books Goose and Duck George, Jean Craighead JE - Level 3 K/2 Iris and Walter the Sleepover Guest, Elissa Haden JE - Level 3 K/2 S Happy Go Ducky Houran, Lori Haskins JE - Level 3 K/2 (K-1) Monster School: First Day Frights Keane, David JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) The Best Chef in Second Grade Kenah, Katherine JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) S Ling and Ting: Not Exactly the Same Lin, Grace JE - Level 3 K/2 (1-2) S Emma's Strange Pet Little, Jean JE - Level 3 K/2 Mouse Soup Lobel, Arnold JE - Level 3 K/2 S The Bookstore Ghost Maitland, Barbara JE - Level 3 K/2 Three Stories You Can Read to Your Cat Miller, Sara Swan JE - Level 3 K/2 S September 2013 Pleasanton Public Library Page 1 of -

Internations.Org Seattle - Riga

InterNations.org Seattle - Riga SHORT STORIES & POESY E-BOOK EDITION 2020 FOREWORD Standing at the start of 2021, we look back at the past year and realize a year ago we were unknowingly perched atop a precipice. None of us knew that in the following weeks and months, life as we knew it—the world as we knew it—would change irrevocably. In many ways the destruction of our previous life is complete; and yet, a phoenix has risen from those ashes of our former existence. At the same time that global lockdowns built up walls to separate and “distance” us, InterNations broke down the walls of geography and brought us together in a new, online community. Our calendars, suddenly empty deserts devoid of commutes, office hours, and in-person socializing, instead offered us a new-found wealth of time, time we used to develop untapped talents and unexpected potentials. The microfiction works contained in this collection are the fruit of these creative explorations. Over the course of 2020 dozens of InterNations members set pen to paper, many for the first time ever, and crafted mini-works around given themes and key words. With limits on length ranging from 250-350 words, together we discovered that writing was something of which we are all capable. We particularly applaud those who bravely shared pieces composed in languages other than their mother tongue. We hope that you will all enjoy reading the stories and poems in this e-book, published exclusively for the authors themselves. And we encourage all the authors to continue nurturing their nascent literary talents as we very much look forward to seeing more of your work in 2021! Margie Banin & Claude G. -

Eurovista Special Issue All Texts

From the Editors This is the first new issue of EuroVista to be freely available online. As anticipated in earlier editorials, from now on whole issues and/or individual articles may be downloaded without charge from the EuroVista website (http://www.euro-vista.org/). This includes those back issues that before only were available on the website behind a paywall. We are grateful to the CEP, that has made this possible. The main reason for this change is to make the journal more easily accessible and therefore, we hope and expect, much more widely read. Do please tell all your friends and colleagues the good news! And what a start we have for this new formula! This issue has been compiled and edited by a member of our Editorial Board, Dr Beth Weaver, University of Strathclyde, Scotland. As she writes in her introduction, we believe this to be the first journal ever to devote an entire issue to contributions made by people who have desisted from offending, some of whom may indeed describe themselves as in a continuing process of desistance. People who have committed crimes have usually been treated as subjects of research and sometimes even as its objects, but their own voice has not often been easy to hear. This issue, by contrast, includes writings by people from a large number of countries who set out a diverse range of accounts of and reflections on their own experiences. About the only thing they all have in common is that they have been convicted of offences and are now or have been on a journey towards ways of living in which offending has no place. -

Pletf Television Pbograms

E/i; i, S CO PLETF TELEVISION PBOGRAMS lifton aferson Fair Lewn Garfield Haledon Hawthorne ...*.,,;•½ •,•,½ •.•;•,... :'.' Lodi ß :.;.,: ........ ... :.•. •...•, ß .-• Little Falls .. •.•;.. ½'. %.½ß .,•,:;• ....• ,-• :,:..::.., ...,.... ..... •.•.•.• ½•"• •, %'., . :•.:.:'"'.:..:, Mountain View :;:";,?;•-:? .... • , ,, ...: ß . :, ',]. .. .. .:. .., ..**.•:4%,.•,' , ..•;.:.•:•-•,.. *'•?;::,.• ;orth Haledon ,.•.% •.-.;•,•.,•,..-• Paterson r-ai½ m fon Lakes Park Sin ac fotowa ayne est Pterson LOVELIES OF SHADY LAKE ß ['GUST 17, 1955 VOL. XXX. No. 33 •-.••Little 'Falls .Parki-ng Meter Ordinance WHITE and SHAUGER, Inc. --CalledUnfa, r To MerchantsBy Stokes A GOODNA]•. TO • * ,' ,;ER iiiii LI•'I'LEFALLS --A parking meter ordinance ,s,cheduled _for for. • I firstunfairreading to merchants'Monda,y, byAugust Committeeman 18, was branded Dr. Jamesas Stokesharmful at andthe F URN IT U RE ....•'•'• Township Committee meeting this •veek. [.lying Room Bed Room Dining Room Stokes, a consis'ent opponent RUGS AHD CARPETS A SPECIALTY ..: :-• wasofthe registeringparking authority'his opposition saidheon leadSchumacher to a "seriousasserted problem'this, could that QUALITY and LOW PRICE ' the ordinancebecause he might only a total re.evaluationwould -- 39 Years Serving tile Public -- not be.present at the reading. correct. 435 STRAIGHT ST. MU. 4-71130 PATE•ON-,-N. J. The .new law wouldprovide a Whenthe problemwas refer- 240MARKi• ST. (ClWroll Pllaa Hotel Bldg.) MU4-79T• parking meter system for the red to Mayor Jacob De Young, he first time in the township's his- noted that the four companies in- tory.-The money collected would terviewed by' the committee for go to the parking authority to al- the revaluation said they could low them to buy land for off- not start earlier than next Jun.e. street parking and pay salaries Early in the session the com- of attendants. -

Xavier Sequeira Acknowledgments

Journey to Canada Xavier Sequeira Acknowledgments ’m fortunate to have experienced so many nice things, met Iso many nice and interesting people, visited and lived in so many nice and interesting places. I have attempted to capture some of those experiences in the following pages. There are so many more events and people that I fail to remember now but who have been part of the exciting life I’ve lived. Here are some of the events in my life with people I’ve met along the way, who for better or worse have made an impression on me. The following pages record the people, places and par- ties, that have made my life what it is. If we met, and your name is not here, just blame it on my memory. This is my life, in my own words. Chapter 1 t was a cool Sunday morning in April, 1946. My father, John ISequeira, had been in attendance at mass that Sunday. After the service wrapped up, Dad met up with the local Goan com- munity of Iringa. The community was relatively small: about ten families or so. Today he had some special news to share: earlier that day, in the very early hours of morning, l was born at the Iringa General Hospital! Some skeptical eyebrows met his announcement — and I don’t blame them. How were his friends supposed to believe that my dad had a son on what just happened to be April 1st or April Fool’s Day. April Fools pranks were taken pretty seriously at that time. -

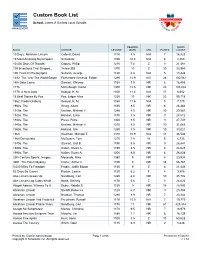

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: James A Garfield Local Schools MANAGEMENT READING WORD BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® LEVEL GRL POINTS COUNT 10 Days: Abraham Lincoln Colbert, David 1110 8.5 N/A 7 16,823 10 Most Amazing Skyscrapers Scholastic 1100 10.4 N/A 6 8,263 10,000 Days Of Thunder Caputo, Philip 1210 7.6 Z 8 21,491 100 Inventions That Shaped... Yenne, Bill 1370 10 Z 10 33,959 100 Years In Photographs Sullivan, George 1120 6.8 N/A 5 13,426 1492: The Year The World Began Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe 1280 12.9 N/A 24 100,581 14th Dalai Lama Stewart, Whitney 1130 7.9 NR 6 18,455 1776 McCullough, David 1300 12.5 NR 23 105,034 1776: A New Look Kostyal, K. M. 1100 11.4 N/A 17 6,652 18 Best Stories By Poe Poe, Edgar Allan 1220 10 NR 22 99,118 1862, Fredericksburg Kostyal, K. M. 1160 11.6 N/A 5 7,170 1900s, The Woog, Adam 1160 8.5 NR 8 26,484 1910s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1280 8.5 NR 10 29,561 1920s, The Hanson, Erica 1170 8.5 NR 9 28,812 1930s, The Press, Petra 1300 8.5 NR 9 27,749 1940s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1210 8.5 NR 10 31,665 1960s, The Holland, Gini 1260 8.5 NR 10 33,021 1968 Kaufman, Michael T. 1310 10.9 N/A 11 36,546 1968 Democratic McGowen, Tom 1270 7.8 W 5 6,733 1970s, The Stewart, Gail B. -

Lights! Camera! Gallop!

Lights! Camera! Gallop! The story of the horse in film By by Lesley Lodge Published by Cooper Johnson Limited Copyright Lesley Lodge © Lesley Lodge, 2012, all rights reserved Lesley Lodge has reserved her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. ISBN: 978-0-9573310-1-3 Cover photo: Running pairs Copyright Paul Homsy Photography Taken in Ruby Valley in northern Nevada, USA. Shadowfax – a horse ‘so clever and obedient he doesn’t have a bridle or a bit or reins or a saddle’ (Lord of the Rings trilogy) Ah, if only it was all that simple . Contents Chapter One: Introducing... horses in film Chapter Two: How the horse became a film star Chapter Three: The casting couch: which horse for which part? Chapter Four: The stars – and their glamour secrets Chapter Five: Born free: wild horses and the wild horse film Chapter Six: Living free: wild horse films around the world Chapter Seven: Comedy: horses that make you laugh Chapter Eight: Special effects: a little help for horses Chapter Nine: Tricks and stunts: how did he do that? Chapter Ten: When things go wrong: spotting fakes and mistakes Chapter Eleven: Not just a horse with no name: the Western Chapter Twelve: Test your knowledge now Quotes: From the sublime to the ridiculous Bibliography List of films mentioned in the book Useful websites: find film clips – and more – for free Acknowledgements Photo credits Glossary About the author Chapter One Introducing….horses in film The concept of a horse as a celebrity is easy enough to accept – because, after all, few celebrities become famous for actually doing much. -

Otis and the Tornado Great Books for Kids 2011 Every Kid’S Life Should Be Filled with Books — at Home, at School and Anywhere They Travel

featuring the #1 New York Times Bestselling LOREN LONG Otis and the Tornado Great Books for Kids 2011 EVERY KID’S LIFE SHOULD BE FILLED WITH BOOKS — AT HOME, AT SCHOOL AND ANYWHERE THEY TRAVEL. Kids take great pride in owning books, so giving them for holidays and special occasions is a wonderful idea. Great Books for Kids presents recent, high quality publications for kids of all ages — and their families. The Cuyahoga County Public Library staff recommend that you consider these titles for gift-giving throughout the year. Visit cuyahogalibrary.org for branch locations. The books and toys in this guide are also available to borrow from Cuyahoga County Public Library. Note: The prices listed for each selection are the publishers’ suggested prices and may vary in area stores. ©2011 Cuyahoga County Public Library Illustrations from Otis and the Tornado used with the permission of Philomel Books, an imprint of Penguin Group USA. ©2011 by Loren Long. featuringOTIS AND THE TORNADO by Loren Long Philomel Books / 9780399254772 / $17.99 Recorded Books Book & CD / 9781461835325 / $40.75 Otis the “putt puff puttedy chuff” tractor is back! While Otis attempts to befriend a grumpy bull, he must also protect the farm animals from an approaching tornado. NO SLeeP FOR THE SHeeP RRRALPH by Lois Ehlert LITTLE WHITE RABBIT by Kevin Henkes by Karen Beaumont / illustrated by Jackie Urbanovic Beach Lane Books / 9781442413054 / $17.99 Greenwillow Books / 9780062006424 / $16.99 Harcourt Children’s Books / 9780152049690 / $16.99 Recorded Books Book & CD / 9781461843665 / $40.75 Have fun hopping along with little white rabbit as he explores Sheep only wants to sleep but he keeps getting interrupted by Ralph, the dog, can talk! You and your little one will laugh his world and wonders what it would be like to be green as the other farm animals.. -

Springsteen, a Three-Minute Song, a Life of Learning

Springsteen, A Three-Minute Song, A Life of Learning by Jin Thindal M.Ed., University of Sheffield, 1992 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Curriculum Theory and Implementation Program Faculty of Education © Jin Thindal 2019 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2019 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Jin Thindal Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title: Springsteen, A Three-Minute Song, A Life of Learning Examining Committee: Chair: Lynn Fels Professor Celeste Snowber Senior Supervisor Professor Allan MacKinnon Supervisor Associate Professor Michael Ling Internal Examiner Senior Lecturer Walter Gershon External Examiner Associate Professor School of Teaching, Learning & Curriculum Studies Kent State University Date Defended/Approved: December 9, 2019 ii Abstract This dissertation is an autobiographical and educational rendering of Bruce Springsteen’s influence on my life. Unbeknownst to him, Bruce Springsteen became my first proper ‘professor.’ Nowhere near the confines of a regular classroom, he opened the door to a kind of education like nothing I ever got in my formal schooling. From the very first notes of the song “Born in the U.S.A.,” he seized me and took me down a path of alternative learning. In only four minutes and forty seconds, the song revealed how little I knew of the world, despite all of my years in education, being a teacher, and holding senior positions. Like many people, I had thought that education was gained from the school system. -

Zorro Visible Fictions

HOT Season for Young People 2011-2012 Teacher Guidebook Zorro Visible Fictions tson ber Ro las ug Do y b to ho P Season Sponsor A note from our Sponsor ~ Regions Bank ~ Jim Schmitz Executive Vice President Area Executive Middle Tennessee Area For over 125 years Regions has been proud to be a part of the Middle Tennessee community, growing and thriving as our area has. From the opening of our doors on September 1, 1883, we have committed to this community and our customers. One area that we are strongly committed to is the education of our students. We are proud to support TPAC’s Humanities Outreach in Tennessee Program. What an important sponsorship this is – reaching over 25,000 students and teachers – some students would never see a performing arts production with- out this program. Regions continues to reinforce its commitment to the communities it serves and in ad- dition to supporting programs such as HOT, we have close to 200 associates teaching financial literacy in classrooms this year. Season Sponsor Thank you, teachers, for giving your students this wonderful opportunity. They will certainly enjoy the experience. You are creating memories of a life- time, and Regions is proud to be able to help make this opportunity possible. Did you know that Krispy Kreme Doughnut Corporation helped groups across the nation raise more than $30 Million last year? Krispy Kreme’s Fundraising program is fast, easy, extremely profitable! But most importantly, it is FUN! For more information about how Krispy Kreme can help your group raise some dough, visit krispykreme.com or call a Neighborhood Shop near you! Contents Synopsis pages 2-3 The Author page 4 Historic Setting page 5 Comic Book Influence page 6 Exploration One page 7 Custom Crusader Exploration Two pages 8-9 A Horse, of Course Exploration Three page 10 The Play’s the Thing Exploration Four page 11 Destined for Greatness Exploration Five page 12 How Do You Find Bravery? TPAC Guidebook written and compiled by Lattie Brown with excerpts from the Zorro - Study Guide by Visible Fictions, as noted.