Springsteen, a Three-Minute Song, a Life of Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

Issue 61 September 2014 - November 2014

Issue 66 Issue 61 September 2014 - November 2014 December 2015 In Our Backyard. Creative Shots Photo Club’s Annual Photo- graphic exhibition. January 2016 Kick off the new year by joining the brand new Sarina Commu- nity Choir - Sarina Sings! February 2016 You...Me...Us Get your tickets to Guy Sebastian’s re- gional tour from the MECC today. Drop in on Design / Slade Point Community Centre, 16 January Young people from 10 - 17 can be mentored by local identities Marie Mourtoulakis and Matthew Izard to create their own skate- board deck design. This is a FREE workshop so get in quick! Index Mackay Events 3 Mackay Workshops & Meetings 7 Art is in calendar of the arts is a quarterly Sarina & Surrounding Area 14 publication, produced by Mackay Regional Council. Pioneer Valley 15 To receive Art is in by post, contact the Arts Development Officer at Bowen Basin 17 Mackay Regional Council on 1300 622 529 Proserpine, Airlie Beach & Bowen 17 or email [email protected] Council has an on-going responsibility to provide Museums & Galleries 17 communication suitable to the needs of all residents. Anyone who wishes to receive council Markets 20 publications in an alternative preferred format, should phone 1300 622 529 or email [email protected] Contributions All contributions from Mackay region are welcome. Listings for arts and cultural activities and events are free. Quarter, half and full page advertising rates are available by contacting council’s Arts Development Officer. Submit your content to - http://www.mackay.qld.gov.au/nested_content/ web_forms/mackay_creative_ebulletin Closing date for next issue contributions is Thursday, 14 January 2016. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Building Cold War Warriors: Socialization of the Final Cold War Generation

BUILDING COLD WAR WARRIORS: SOCIALIZATION OF THE FINAL COLD WAR GENERATION Steven Robert Bellavia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Andrew M. Schocket, Advisor Karen B. Guzzo Graduate Faculty Representative Benjamin P. Greene Rebecca J. Mancuso © 2018 Steven Robert Bellavia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This dissertation examines the experiences of the final Cold War generation. I define this cohort as a subset of Generation X born between 1965 and 1971. The primary focus of this dissertation is to study the ways this cohort interacted with the three messages found embedded within the Cold War us vs. them binary. These messages included an emphasis on American exceptionalism, a manufactured and heightened fear of World War III, as well as the othering of the Soviet Union and its people. I begin the dissertation in the 1970s, - during the period of détente- where I examine the cohort’s experiences in elementary school. There they learned who was important within the American mythos and the rituals associated with being an American. This is followed by an examination of 1976’s bicentennial celebration, which focuses on not only the planning for the celebration but also specific events designed to fulfill the two prime directives of the celebration. As the 1980s came around not only did the Cold War change but also the cohort entered high school. Within this stage of this cohorts education, where I focus on the textbooks used by the cohort and the ways these textbooks reinforced notions of patriotism and being an American citizen. -

Strange Brew√ Fresh Insights on Rock Music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006

M i c h a e l W a d d a c o r ‘ s πStrange Brew Fresh insights on rock music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006 L o n g m a y y o u r u n ! A tribute to Neil Young: still burnin‘ at 60 œ part two Forty years ago, in 1966, Neil Young made his Living with War (2006) recording debut as a 20-year-old member of the seminal, West Coast folk-rock band, Buffalo Springfield, with the release of this band’s A damningly fine protest eponymous first album. After more than 35 solo album with good melodies studio albums, The Godfather of Grunge is still on fire, raging against the System, the neocons, Rating: ÆÆÆÆ war, corruption, propaganda, censorship and the demise of human decency. Produced by Neil Young and Niko Bolas (The Volume Dealers) with co-producer L A Johnson. In this second part of an in-depth tribute to the Featured musicians: Neil Young (vocals, guitar, Canadian-born singer-songwriter, Michael harmonica and piano), Rick Bosas (bass guitar), Waddacor reviews Neil Young’s new album, Chad Cromwell (drums) and Tommy Bray explores his guitar playing, re-evaluates the (trumpet) with a choir led by Darrell Brown. overlooked classic album from 1974, On the Beach, and briefly revisits the 1990 grunge Songs: After the Garden / Living with War / The classic, Ragged Glory. This edition also lists the Restless Consumer / Shock and Awe / Families / Neil Young discography, rates his top albums Flags of Freedom / Let’s Impeach the President / and highlights a few pieces of trivia about the Lookin’ for a Leader / Roger and Out / America artist, his associates and his interests. -

Fabric Mulch for Tree and Shrub Plantings, Kansas State University, August 2004

KANSAS Fabric Mulch for Tree FOREST SER VICE and Shrub Plantings KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY What is Fabric Mulch? though most last well beyond the caution in riparian areas that flood Fabric mulch (often referred to time necessary to establish tree and periodically. Flooding can lower as Weed Barrier, one of many brand shrub plantings. Excessive durabil- the effectiveness of the mulch by names) is used to reduce vegetative ity results from inordinate specifi- dislocation and soil deposition. competition in newly planted trees cations and from shade created by Fabric mulch inhibits root sprouting and shrubs. This is accomplished by trees and shrubs that prevents dete- of shrubs. Root sprouting increases applying fabric over the top of trees rioration. New products are being stem density, providing valuable and shrubs after planting, cutting a tested to address this issue. wildlife habitat. hole in the fabric, and pulling the trees and shrubs through the hole. It When Should Fabric Fabric Mulch is made of a black, woven, perme- Mulch be Used? Specifications able, polypropylene geotextile that Fabric mulch is appropriate to Fabric mulch is available in can withstand the trampling of deer help establish windbreaks, shel- a variety of sizes and specifica- and deterioration from sunlight. terbelts, living snowfences, and tions. It can be purchased in rolls Fabric mulches conserve soil mois- other small tree and shrub plant- that can be applied by machine, or ture by reducing evaporation. Fabric ings. Fabric should be used with in squares that can be applied by mulches eventually biodegrade, hand. Rolls may contain from 300 to 750 feet of fabric and range from 4 to 10 feet wide. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

C9268c Baylor.B

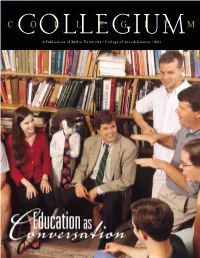

Driving North 1981 COLLEGIUM Let me have the grace to speak of this for I would mind what happens here. — Robert Duncan collegium The darkness was Protestant that year, but not A Publication of Baylor University • College of Arts & Sciences • 2001 with individual conscience, the hymn of the south, or the priesthood of the believer. Haunted, driving north, I watched the horizon gray over Oklahoma, the rim of fires drifting down from Manitoba. I stepped out hours later to the first cold of September, a season’s end. The magnolias were already old those last evenings, reflected in the watery light of summer rain. The air was dark with words. But this spring, a hymn heard through a distant window brought back the years before: The places where crepe myrtle blooms early and late, where old bells echo from a green Handel and Mendelssohn and all the music of Passover, where almost every lamppost has a name and shadows cross our days without erasing joy. Dr. Jane Hoogestraat (B.A., 1981) Poet and Associate Professor of English, Southwest Missouri State University College of Arts and Sciences PO Box 97344 Waco, TX 76798-7344 Change Service Requested A Letter from the Dean This issue of Collegium Studies sponsored a symposium on “Civil Society and the Search for focuses on the relationship Justice in Russia.” The symposium, held in February 2001, involved between professors and stu- research presentations from our faculty and students, as well as from dents. Every time I have heard prominent American and Russian scholars and journalists; the papers graduating seniors speak about currently are in press. -

Texas Review's Gordian Review

The Gordian Review Volume 2 2017 The Gordian Review Volume 2, 2017 Texas Review Press Huntsville, TX Copyright 2017 Texas Review Press, Sam Houston State University Department of English. ISSN 2474-6789. The Gordian Review volunteer staff: Editor in Chief: Julian Kindred Poetry Editor: Mike Hilbig Fiction Editor: Elizabeth Evans Nonfiction Editor: Timothy Bardin Cover Design: Julian Kindred All images were found, copyright-free, on Shutterstock.com. For those graduate students interesting in having their work published, please submit through The Gordian Review web- site (gordianreview.org) or via the Texas Review Press website (texasreviewpress.org). Only work by current or recently graduated graduate students (Masters or PhD level) will be considered for publication. If you have any questions, the staff can be contacted by email at [email protected]. Contents 15 “Nightsweats” Fiction by James Stewart III 1 “A Defiant Act” 16 “Counting Syllables” Poetry by Sherry Tippey Nonfiction by Cat Hubka 4 “Echocardiogram” 17 “Missed Connections” 5 “Ants Reappear Like Snowbirds” 6 “Bedtime Story” Poetry by Alex Wells Shapiro 6 “Simulacrum” 21 “Feralizing” 7 “Cat Nap” 21 “Plugging” 22 “Duratins” 23 “Opening” Nonfiction by Rebekah D. Jerabek 7 “Of Daughters” 23 “Desiccating” Poetry by Kirsten Shu-ying Chen Acknowledgements 14 “Astronimical dawn” 15 “Brainstem” Author Biographies A Defiant Act by James Stewart III father walks to the back of the family mini-van balancing four ice cream cones in his two hands. He’s holding them away from hisA body so they don’t drip onto his stained jeans in the midsummer heat. He somehow manages to open the back hatch of the van while balancing the treats. -

Daughter Album If You Leave M4a Download Download Verschillende Artiesten - British Invasion (2017) Album

daughter album if you leave m4a download Download Verschillende artiesten - British Invasion (2017) Album. 1. It's My Life 2. From the Underworld 3. Bring a Little Lovin' 4. Do Wah Diddy Diddy 5. The Walls Fell Down 6. Summer Nights 7. Tuesday Afternoon 8. A World Without Love 9. Downtown 10. This Strange Effect 11. Homburg 12. Eloise 13. Tin Soldier 14. Somebody Help Me 15. I Can't Control Myself 16. Turquoise 17. For Your Love 18. It's Five O'Clock 19. Mrs. Brown You've Got a Lovely Daughter 20. Rain On the Roof 21. Mama 22. Can I Get There By Candlelight 23. You Were On My Mind 24. Mellow Yellow 25. Wishin' and Hopin' 26. Albatross 27. Seasons In the Sun 28. My Mind's Eye 29. Do You Want To Know a Secret? 30. Pretty Flamingo 31. Come and Stay With Me 32. Reflections of My Life 33. Question 34. The Legend of Xanadu 35. Bend It 36. Fire Brigade 37. Callow La Vita 38. Goodbye My Love 39. I'm Alive 40. Keep On Running 41. The Hippy Hippy Shake 42. It's Not Unusual 43. Love Is All Around 44. Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood 45. The Days of Pearly Spencer 46. The Pied Piper 47. With a Girl Like You 48. Zabadak! 49. I Only Want To Be With You 50. Here It Comes Again 51. Don't Let the Sun Catch You Crying 52. Have I the Right 53. Darling Be Home Soon 54. Only One Woman 55. -

Download RISJ Annual Report 2016-2017

Annual Report 2016-2017 Contents Reuters Institute Annual Report 2016-2017 01 Foreword 02 Preface 04 The Year in Review 10 The Journalist Fellowship Programme 26 Research and Publication 46 Events 56 About us Opposite: A protester holds a national flag as a bank branch, housed in the magistracy of the Supreme Court of Justice, burns during a rally against Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro, in Caracas, Venezuela June 12, 2017. REUTERS/Carlos Garcia Rawlins Reuters Institute - Annual Report 2016-17 00 Foreword Preface Monique Villa Alan Rusbridger CEO - Thomson Reuters Foundation Chair of the Steering Committee ‘What is the Thomson Reuters It’s difficult not to feel a twinge And then there are the journalism Foundation doing to counter the We are navigating through of sympathy for anyone editing fellows who fly in from all quarters issue of fake news?’ I lost count uncharted waters. It is precisely at or otherwise running a media of the globe to spend months of the many times I got asked that times like these that we need an organisation these days. Someone in Oxford solving problems and question this year. My answer is institution able to guide the industry once memorably compared the thinking about diverse possibilities. simple: we fund one of the world’s with courage and competence. I know task to rebuilding a 747 in mid-flight. leading centres promoting excellence we are in good hands: Alan Rusbridger, the It’s very difficult to see where you’re These opportunities to talk, share, think, in journalism. Chair of the Steering Committee, is certainly the flying. -

Acoustic Sounds Catalog Update

WINTER 2013 You spoke … We listened For the last year, many of you have asked us numerous times for high-resolution audio downloads using Direct Stream Digital (DSD). Well, after countless hours of research and development, we’re thrilled to announce our new high-resolution service www.superhirez.com. Acoustic Sounds’ new music download service debuts with a selection of mainstream audiophile music using the most advanced audio technology available…DSD. It’s the same digital technology used to produce SACDs and to our ears, it most closely replicates the analog experience. They’re audio files for audiophiles. Of course, we’ll also offer audio downloads in other high-resolution PCM formats. We all like to listen to music. But when Acoustic Sounds’ customers speak, we really listen. Call The Professionals contact our experts for equipment and software guidance RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT RECOMMENDED SOFTWARE Windows & Mac Mac Only Chord Electronics Limited Mytek Chordette QuteHD Stereo 192-DSD-DAC Preamp Version Ultra-High Res DAC Mac Only Windows Only Teac Playback Designs UD-501 PCM & DSD USB DAC Music Playback System MPS-5 superhirez.com | acousticsounds.com | 800.716.3553 ACOUSTIC SOUNDS FEATURED STORIES 02 Super HiRez: The Story More big news! 04 Supre HiRez: Featured Digital Audio Thanks to such support from so many great customers, we’ve been able to use this space in our cata- 08 RCA Living Stereo from logs to regularly announce exciting developments. We’re growing – in size and scope – all possible Analogue Productions because of your business. I told you not too long ago about our move from 6,000 square feet to 18,000 10 A Tribute To Clark Williams square feet.