Texas Review's Gordian Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCENE ONE (An Empty Stage. There Is a Podium and a Projector Screen

SCENE ONE (An empty stage. There is a podium and a projector screen emblazoned with the logo “WELLSTONE PROJECT.” A spotlight comes up on STEPHEN, who stands at the podium, dressed in formal attire. He carries a drink in his hand.) STEPHEN Thank you all for being here tonight – for your support – for honoring my brother’s life and legacy. (as HE speaks, the screen behind him flashes a portrait of Paul Wellstone) It would mean the world to them – Paul, and Sheila (the screen flashes a photo of Paul and Sheila together) – to see you all here tonight. (he sips his drink liberally and shakes himself out) I just want to apologize in advance – I never had my brother’s knack for public speaking. (HE chuckles nervously) But I always said… I always said my brother had a way of bringing people together… Sometimes in ways we might not expect. But – (the screen flashes a photo of a beach in Maryland) One way or another, it all leads back… to this. (without looking backward, the screen raises out of view, and the set changes to the beach seen in the photo, complete with a sunbathing SHEILA, reclining on a beach chair, reading a book) The beaches our parents took us to as kids… I haven’t set foot here in years, but I can still see it all like it was yesterday. (HE mimes to various parts of the set) The stand where they used to sell popsicles on hot days. (another) And over there, see? That’s where I built the biggest sandcastle you’d ever seen… Until Paul stepped in it. -

Thad Jones Discography Copy

Thad Jones Discography Compiled by David Demsey 2012-15 Recordings released during Thad Jones’ lifetime, as performer, bandleader, composer/arranger; subsequent CD releases are listed where applicable. Each entry lists Thad Jones compositions/arrangements contained on that recording. Album titles preceded by (•) are contained in the Thad Jones Archive collection. I. As a Leader or Co-Leader Big Band Leader or Co-Leader (chronological): • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Live at the Vanguard (rec. 1/7 [sic], 3/21/66) [live recording donated by George Klabin] Contains: All My Yesterdays (2 versions), Backbone, Big Dipper (2 versions), Mean What You Say, Morning Reverend, Little Pixie, Willow Weep for Me (Brookmeyer), Once Around, Polka Dots and Moonbeams (small group), Low Down, Lover Man, Don’t Ever Leave Me, A-That’s Freedom • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, On Tour (rec. varsious dates and locations in Europe) Discs 1-7, 10-11 [see Special Recordings section below] On iTunes. • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, In the Netherlands (rec. 1974) [unreleased live recording donated by John Mosca] • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Presenting the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra (rec. 5/4-5-6/66) Solid State UAL18003 Contains: Balanced Scales = Justice, Don’t Ever Leave Me, Mean What You Say, Once Around, Three and One • Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Opening Night (rec. 1[sic]/7/66, incorrect date; released 1990s) Alan Grant / BMG Ct. # 74321519392 Contains: Big Dipper, Polka Dots and Moonbeams (small group), Once Around, All My Yesterdays, Morning Reverend, Low Down, Lover Man, Mean What You Say, Don’t Ever Leave Me, Willow Weep for Me (arr. -

Cultural Times

The MultiCultural Center’s Cultural Times Spring Semester 2003 Humboldt State University The MultiCultural Center’s Staff Paris Adkins Lindsey Allen Kerry Bailey Rebecca Breksa Ivonne Castillo Wendy Y Castillon Paula Cedillo Chris Cook Marie Kristina Cox Hoang Dinh Solana Foo Enika K.Franco Elizabeth Jimenez Antonette (Toni) I. Jones Daeng Khoupradit, Alexis Lewis Hazel E.Lodevico Adriana Lopez Thanh Luong Nicholas I Mathis Brandon McQuien Juan Mendez Aunjelique Meraz Daniela Molina Rishi Nakra Nam Nguyen Tyler Paik-Nicely Miacah Pugh, Alex V Robinson Denia Sanabria Marcee Stamps Reginald Thomas II Isaac Too Pata Vang, Massey Verletta John Volk, Janine Wolfe, Precious Yamaguchi Editor’s Note Sometimes the most challenging experiences we face turn out to be the most rewarding. It is the struggle that we are encountered when we take action to overcome the adversities in life, the internal conflict of our own abilities to accomplish our goals and all that we learn about ourselves along the way that create personal as well as social achievements. Sometimes we can be accomplishing more than we even know, by doing things such as participating in activism or causes we believe in, vol- unteering, going to school to educate ourselves or even actions that are often very important but easily overlooked like being a good parent, a generous friend or being a loving partner, that all help build identity, self-worth and help the people around us. The ways we can improve the lives of others and ourselves is endless. With every goal that is accomplished, a new goal lies not far ahead and here at the MultiCultural Center, we have experienced a semester full of achievements made by students that have brought cultural unity and education within our campus as we are constantly seeking ways to make improvements while still having fun at the same time! The events created by students, faculty and members of the community for Black History Month, Q- Fest, Celebración Latina and the MultiCultural Center’s annual Diversity Conference are shown throughout the newsletter. -

Pilot Testing of a Transition Tool for Rural Palliative Patients and Their Family Caregivers

PILOT TESTING OF A TRANSITION TOOL FOR RURAL PALLIATIVE CARE PATIENTS AND THEIR FAMILY CAREGIVERS A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Nursing In the College of Nursing University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Lori Jean Cooper Copyright Lori Jean Cooper, March 2012. All Rights Reserved PERMISSION TO USE This thesis is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Nursing from the University of Saskatchewan. I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department, the Dean of the College of Nursing. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean of the College of Nursing University of Saskatchewan 107 Wiggins Road Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5E5 Canada i ABSTRACT There is a consensus in the literature that end of life care in rural areas is suboptimal. -

C9268c Baylor.B

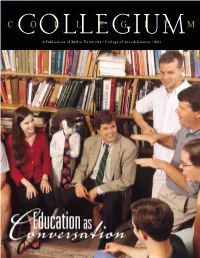

Driving North 1981 COLLEGIUM Let me have the grace to speak of this for I would mind what happens here. — Robert Duncan collegium The darkness was Protestant that year, but not A Publication of Baylor University • College of Arts & Sciences • 2001 with individual conscience, the hymn of the south, or the priesthood of the believer. Haunted, driving north, I watched the horizon gray over Oklahoma, the rim of fires drifting down from Manitoba. I stepped out hours later to the first cold of September, a season’s end. The magnolias were already old those last evenings, reflected in the watery light of summer rain. The air was dark with words. But this spring, a hymn heard through a distant window brought back the years before: The places where crepe myrtle blooms early and late, where old bells echo from a green Handel and Mendelssohn and all the music of Passover, where almost every lamppost has a name and shadows cross our days without erasing joy. Dr. Jane Hoogestraat (B.A., 1981) Poet and Associate Professor of English, Southwest Missouri State University College of Arts and Sciences PO Box 97344 Waco, TX 76798-7344 Change Service Requested A Letter from the Dean This issue of Collegium Studies sponsored a symposium on “Civil Society and the Search for focuses on the relationship Justice in Russia.” The symposium, held in February 2001, involved between professors and stu- research presentations from our faculty and students, as well as from dents. Every time I have heard prominent American and Russian scholars and journalists; the papers graduating seniors speak about currently are in press. -

BOY S GOLD Mver’S Windsong M If for RCA Distribim

Lion, joe f AND REYNOLDS/ BOY S GOLD mver’s Windsong M if For RCA Distribim ARM Rack Jobbe Confab cercise In Commi i cation ista Celebrates 'st Year ith Convention, Concert tal’s Private Stc ijoys 1st Birthd , usexpo Makes I : TED NUGENFS HIGH WIRED ACT. Ted Nugent . Some claim he invented high energy. Audiences across the country agree he does it best. With his music, his songs and his very plugged-in guitar, Ted Nugent’s new album, en- titled “Ted Nugent,” raises the threshold of high energy rock and roll. Ted Nugent. High high volume, high quality. 0n Epic Records and Tapes. High Energy, Zapping Cross-Country On Tour September 18 St. Louis, Missouri; September 19 Chicago, Illinois; September 20 Columbus, Ohio; September 23 Pitts, Penn- sylvania; September 26 Charleston, West Virginia; September 27 Norfolk, Virginia; October 1 Johnson City, Tennessee; Octo- ber 2 Knoxville, Tennessee; October 4 Greensboro, North Carolina; October 5 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; October 8 Louisville, x ‘ Kentucky; October 11 Providence, Rhode Island; October 14 Jonesboro, Arkansas; October 15 Joplin, Missouri; October 17 Lincoln, Nebraska; October 18 Kansas City, Missouri; October 21 Wichita, Kansas; October 24 Tulsa, Oklahoma -j 1 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC-RECORD WEEKLY C4SHBCX VOLUME XXXVII —NUMBER 20 — October 4. 1975 \ |GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW cashbox editorial Executive Vice President Editorial DAVID BUDGE Editor In Chief The Superbullets IAN DOVE East Coast Editorial Director Right now there are a lot of superbullets in the Cash Box Top 1 00 — sure evidence that the summer months are over and the record industry is gearing New York itself for the profitable dash towards the Christmas season. -

Congressional Record-House. 1581

·- 1893. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. 1581 The reading of the bill was resumed at line 6, on page 84. Branch, at Marion, Ind., page 93, line 6, after the word " con . , The next amendmentof the Committee on Appropriations was, struction," to insert "and repairs;" so as to read: under the head of" National Home· for Disabled Volunteer Sol For construction and repairs, includin~ the same objects spo.:J ified under diers," in the appropriation for the Central Branch, at Dayton, this head tor the Central Branch, IS:20,264.55. Ohio, page 85, line 7, to reduce the appropriationfor subsistence The amendment was agreed to. from $319,610 to $317,000. The next amendment was, on page 93, line 16, to change the The amendment was agreed to. total of the appropriations for the Marion Branch, at Marion, The next amendment was, on page 85, line 14, under the head Ind., from $2,353,163.89 to $2,360,663-89. of "National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers." to reduce The amendment was agreed to. the expenditure for clothing at the Central Branch; at Dayton, The next amendment was, on page 93, under the head of ' ' State Ohio, from $76,800 to $74,000. or Territo rial homes,'' line 22, after the word " eigh ty-eig :) t," to The amendment was agreed to. strike out "each;" so as to read: The next amendment was, on page 86, line 17, after the words For continuing aid to State or Territorial homes for the support o! dis 11 For construction " to insert " and repairs," and in line 22, bs abled volunteer soldiers in conformity with the act approved August Z7, fore the word'; cents," to strike out "sixty-five thousand one 1888, $575,000. -

Still Competition : the Listeners Guide to Cheap Trick Kindle

STILL COMPETITION : THE LISTENERS GUIDE TO CHEAP TRICK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Professor of Psychology Robert Lawson | 282 pages | 20 Nov 2017 | Friesenpress | 9781525512261 | English | none Still Competition : The Listeners Guide to Cheap Trick PDF Book Nice book of different licks alot of what Rick uses in his music. Refresh and try again. View Product. The Joe Budden Network. Questlove Supreme. A must read for hardcore Cheap Trick fans and even for the casual fan or, especially any new, first-time fans. About this product Product Information Guitar Educational. Although, the author doesn't pull any punches about some of CT's failings in the mid thru late '80s. Short and sweet, about 25 minutes per. Fresh new killer format for a rock book - I learned a ton about Cheap Trick from this book. Barstool Sports. Pepper Live. Surrender Outtake Carlton Duff. Highly recommend this publication. Return to Book Page. Apparently the co. Obviously, the song makes the story sound like it's about a young woman. Rush: The Illustrated History 4. Lawson, but the Cheap Trick fan community, too. June 9 Ken can I buy you a beer?! Since the s, Cheap Trick has entertained countless audiences across the world with their unique brand of rock 'n' roll, featuring the eccentric stylings of guitarist Rick Nielsen. Mind you, I understand personal opinions will vary tremendously when it comes to music. December 8, Format: Paperback This book is a must buy! Still Competition : The Listeners Guide to Cheap Trick Writer Cheeeek that out dude. Warner Bros. Add Comment. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. -

February 26, 2013 - Uvm, Burlington, Vt Uvm.Edu/~Watertwr - Thewatertower.Tumblr.Com

volume 13 - issue 6 - tuesday, february 26, 2013 - uvm, burlington, vt uvm.edu/~watertwr - thewatertower.tumblr.com by benberrick UVM, we need to have a talk. I know things have been hard lately; with the transfer of presidential power, budget cuts, and communication breakdowns all over the place, it’s been nothing short of crazy out here. I understand that you need to relieve stress and chill out, but I just can’t condone the method that you have cho- sen. Just because everyone else is doing it, doesn’t make it okay, UVM, and no matter what kind of peer pressure is there, I expect better from you. So we need to talk about this. No, I’m not talking about all the mas- turbation—honestly, that’s healthy and in the future I’ll knock before I come in. We need to talk about the Harlem Shake. I know why you did it. Heck, there have been times when I’ve wanted to do it myself. Aft er exploding two weeks ago, the Harlem Shake went from something that only a few weirdo skateboarders did, to a by kerrymartin meme of epidemic proportions. Sure, the Keeping up with national politics, for as a tough contest between two intelli- Davis Center; it’s a point that seems obvi- fi rst couple times it was funny, clever even. all the work it takes, bears bitter fruit. I’m gent, qualifi ed, engaged, and open-minded ous, but is oft en overlooked. But within 48 hours, as with most memes, the kind of guy who attacks political apa- women. -

AAHP 499A Rafe Johnson Interviewed by Ryan Thompson on June 26, 2017 3Hours and 1 Minutes | 93 Pages

Joel Buchanan Archive of African American History: http://ufdc.ufl.edu/ohfb Samuel Proctor Oral History Program College of Liberal Arts and Sciences Program Director: Dr. Paul Ortiz 241 Pugh Hall PO Box 115215 Gainesville, FL 32611 (352) 392-7168 https://oral.history.ufl.edu AAHP 499A Rafe Johnson Interviewed by Ryan Thompson on June 26, 2017 3hours and 1 minutes | 93 pages Abstract: In this interview Rafe Johnson gives and account of growing up in Jonesville, Florida with his grandparents. He talks about his encounter with the Ku Klux Klan as a young child with his grandparents. Once his grandparents died he went on to live with his mother in Gainesville, Florida and went to school with to A.Quinn Jones Elementary School and Lincoln High School. At an early age he became involve in the numbers system which is also known as cubing. He also shares his experiences of growing up as a black man within the city of Gainesville. At the age of nineteen, Johnson joins the United States Navy and recalls his experiences within the military system. Once out of the military, Johnson settles again in Gainesville, Florida. Keywords: [Gainesville, Florida; Jonesville, Florida; United States Navy; A. Quinn Jones; Lincoln High School] AAHP 499A Interviewer: Ryan Thompson Interviewee: Rafe Johnson Date: June 26th, 2017 T: Today is Friday, June 26th, 2017. My name is Ryan Thompson from the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida. I’m here at the home of Rafe Johnson in East Gainesville. If you could just say and spell your name please. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

C'est La Grève!

La francophonie nous tient à coeur ! 1976-2006 Spectacle de patinage Vol. 30 No 51 Hearst On ~ Le mercredi 8 mars 2006 1,25$ + T.P.S. artistique de Hearst HA27 À L’INTÉRIEUR Pensée Pensée Un retour dans le temps...........HA2 Pensée Bisson craint la vente de Pensée forêts...........HA03 Les Élans Pensée mènent..........HA26Pensée Pensée PenséePensée Donnez un tout petit peu de pouvoir à un homme et déjà tend à se développer en lui la tentation d'en abuser. Le Carnaval Missinaïbi a de nouveau attiré des milliers de personnes. Encore une fois, les festivités se sont étalées sur une dizaine de jours alors que jeunes et moins jeunes ont profité de la belle température pour s’amuser. La petite Daphné Lacroix et sa grand- maman, Renée Rancourt, ont pris plaisir à glisser sur la neige samedi dernier. Photo disponible au journal Le Nord/CP Ionesco Fortier Valu Mart vendu Un nouveau magasin d’alimentation à Hearst HEARST (FB) – On doit débuter mentation en 1967, comme étudi- Hearst Corner Store qu’il a tion remontait aux années ’30. cette année la construction d’un ant de 13 ans, dans le magasin de revendu en 1990 pour l’achat de M. Fortier indique qu’il a l’in- nouveau magasin d’alimentation son frère, Claude’s Corner Store. Claude’s Valu Mart. tention de demeurer à Hearst. Il 6 à Hearst, suite à la vente de Quand son frère a ouvert La vente de Fortier Valu Mart prend une année sabbatique avant MERCREDI Fortier Valu Mart à National Claude’s Red & White en 1972, il signifie la fin de l’implication de de réorienter sa carrière.