Feminists for Life's Appropriation of First-Wave Feminist Rhetoric And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hermaphrodite Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams

Philosophies of Sex Etching of Julia Ward Howe. By permission of The Boston Athenaeum hilosophies of Sex PCritical Essays on The Hermaphrodite EDITED BY RENÉE BERGLAND and GARY WILLIAMS THE OHIO State UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Philosophies of sex : critical essays on The hermaphrodite / Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1189-2 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-1189-5 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8142-9290-7 (cd-rom) 1. Howe, Julia Ward, 1819–1910. Hermaphrodite. I. Bergland, Renée L., 1963– II. Williams, Gary, 1947 May 6– PS2018.P47 2012 818'.409—dc23 2011053530 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Adobe Minion Pro and Scala Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction GARY Williams and RENÉE Bergland 1 Foreword Meeting the Hermaphrodite MARY H. Grant 15 Chapter One Indeterminate Sex and Text: The Manuscript Status of The Hermaphrodite KAREN SÁnchez-Eppler 23 Chapter Two From Self-Erasure to Self-Possession: The Development of Julia Ward Howe’s Feminist Consciousness Marianne Noble 47 Chapter Three “Rather Both Than Neither”: The Polarity of Gender in Howe’s Hermaphrodite Laura Saltz 72 Chapter Four “Never the Half of Another”: Figuring and Foreclosing Marriage in The Hermaphrodite BetsY Klimasmith 93 vi • Contents Chapter Five Howe’s Hermaphrodite and Alcott’s “Mephistopheles”: Unpublished Cross-Gender Thinking JOYCE W. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

The Radical Feminist Manifesto As Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, and Second Wave Resistance

Southern Journal of Communication ISSN: 1041-794X (Print) 1930-3203 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsjc20 The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance Kimber Charles Pearce To cite this article: Kimber Charles Pearce (1999) The radical feminist manifesto as generic appropriation: Gender, genre, and second wave resistance, Southern Journal of Communication, 64:4, 307-315, DOI: 10.1080/10417949909373145 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10417949909373145 Published online: 01 Apr 2009. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 578 View related articles Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsjc20 The Radical Feminist Manifesto as Generic Appropriation: Gender, Genre, And Second Wave Resistance Kimber Charles Pearce n June of 1968, self-styled feminist revolutionary Valerie Solanis discovered herself at the heart of a media spectacle after she shot pop artist Andy Warhol, whom she I accused of plagiarizing her ideas. While incarcerated for the attack, she penned the "S.C.U.M. Manifesto"—"The Society for Cutting Up Men." By doing so, Solanis appropriated the traditionally masculine manifesto genre, which had evolved from sov- ereign proclamations of the 1600s into a form of radical protest of the 1960s. Feminist appropriation of the manifesto genre can be traced as far back as the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention, at which suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin, and Mary Ann McClintock parodied the Declara- tion of Independence with their "Declaration of Sentiments" (Campbell, 1989). -

Katy Shannahan Edited

1 Katy Shannahan OUHJ 2013 Submission The Impact of Failed Lesbian Feminist Ideology and Rhetoric Lesbian feminism was a radical feminist separatist movement that developed during the early 1970s with the advent of the second wave of feminism. The politics of this movement called for feminist women to extract themselves from the oppressive system of male supremacy by means of severing all personal and economic relationships with men. Unlike other feminist separatist movements, the politics of lesbian feminism are unique in that their arguments for separatism are linked fundamentally to lesbian identification. Lesbian feminist theory intended to represent the most radical form of the idea that the personal is political by conceptualizing lesbianism as a political choice open to all women.1 At the heart of this solution was a fundamental critique of the institution of heterosexuality as a mechanism for maintaining masculine power. In choosing lesbianism, lesbian feminists asserted that a woman was able to both extricate herself entirely from the system of male supremacy and to fundamentally challenge the patriarchal organization of society.2 In this way they privileged lesbianism as the ultimate expression of feminist political identity because it served as a means of avoiding any personal collaboration with men, who were analyzed as solely male oppressors within the lesbian feminist framework. Political lesbianism as an organized movement within the larger history of mainstream feminism was somewhat short lived, although within its limited lifetime it did produce a large body of impassioned rhetoric to achieve a significant theoretical 1 Radicalesbians, “The Woman-Identified Woman,” (1971). 2 Charlotte Bunch, “Lesbians In Revolt,” The Furies (1972): 8. -

Sexual Controversies in the Women's and Lesbian/Gay Liberation Movements

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1985 Politics and pleasures : sexual controversies in the women's and lesbian/gay liberation movements. Lisa J. Orlando University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Orlando, Lisa J., "Politics and pleasures : sexual controversies in the women's and lesbian/gay liberation movements." (1985). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2489. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2489 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POLITICS AND PLEASURES: SEXUAL CONTROVERSIES IN THE WOMEN'S AND LESBIAN/GAY LIBERATION MOVEMENTS A Thesis Presented By LISA J. ORLANDO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1985 Political Science Department Politics and Pleasures: Sexual Controversies in the Uomen's and Lesbian/Gay Liberation Movements" A MASTERS THESIS by Lisa J. Orlando Approved by: Sheldon Goldman, Member Philosophy \ hi (UV .CVvAj June 21, 19S4 Dean Alfange, Jj' Graduate P ogram Department of Political Science Lisa J. Orlando © 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985 All Rights Reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following friends who, in long and often difficult discussion, helped me to work through the ideas presented in this thesis: John Levin, Sheila Walsh, Christine Di Stefano, Tom Keenan, Judy Butler, Adela Pinch, Gayle Rubin, Betsy Duren, Ellen Willis, Ellen Cantarow, and Pam Mitchell. -

A Feminist Conversation

#1 Feminist Reflections NOV. 2018 his essay is the outcome of a conversation between two radical African feminists, TPatricia McFadden and Patricia Twasiima, who unapologetically and with sheer pleasure, think, live and share feminist ideas and imaginaries. Both are part of the African Feminist Refection and Action Group.They live in eastern and southern Africa, respectively, and whilst A FEMINIST CONVERSATION: they are ‘separated’ by distance and age in very conventional ways, their ideas and passions for freedom and being able to live lives of dignity Situating our radical ideas and through their own truths as Black women on their continent, and beyond, are the ties that bind them inseparably as Contemporary African energies in the contemporary Feminists in the 21st century. The conversation they are engaged with and African context in ranges over several core challenges and tasks that have faced feminists ever since the emergence of a public radical women’s politics of resistance against patriarchy. But it also refects Patricia McFadden on new faces of patriarchy and oppression we are confronted with today and on how women`s Patricia Twasiima struggles to counter them can be strengthened. A FEMINIST CONVERSATION: Situating our radical ideas and energies in the contemporary African context women generated a nationalist discourse that Contextualizing the Conversation legitimized their case. Nationalists and fem- omen have resisted oppression and ex- inists collaborated to pursue their common clusion for as long as humans have lived goal -

Betty Friedan and Simone De Beauvoir

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 2 • Issue 1 • 2006 doi:10.32855/fcapital.200601.014 Betty Friedan and Simone de Beauvoir Charles Lemert Betty Friedan died February 4, 2006 on her eighty-fifth birthday. Her passing marks the ending of an era of feminist revolution she helped to spark. Some would say that in America she started it all by herself. Certainly, The Feminine Mystique in 1963 fueled the fire of a civil rights movement that was about to burn out after a decade of brilliant successes in the American South. The rights in question for Friedan were, of course, those of women— more exactly, as it turned out, mostly white women of the middle classes. Unlike other movement leaders of that day, Friedan was a founder and first president of an enduring, still effective, woman’s rights organization. NOW, (the National Organization for Women), came into being in 1966, but soon after was eclipsed by the then rapidly emerging radical movements. Many younger feminists found NOW’s emphasis on political and economic rights too tame for the radical spirit of the moment. The late 1960s were a time for the Weather Underground, the SCUM Manifesto, Black Power and the Black Panthers. By 1968 even SDS was overrun by the radicalizing wave across the spectrum of social movements. Yet, in time, Friedan’s political and intellectual interventions proved the more lasting. SDS and SNCC are today subjects of historical study by academic sociologists who never came close to having their skulls crushed by a madman. But NOW survives in the work of many thousands in every state of the American Union. -

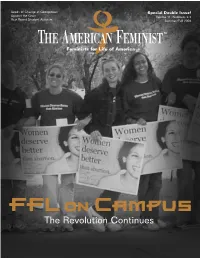

Summer-Fall 2004: FFL on Campus – the Revolution Continues

Seeds of Change at Georgetown Special Double Issue! Against the Grain Volume 11, Numbers 2-3 Year-Round Student Activism Summer/Fall 2004 Feminists for Life of America FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues ® “When a man steals to satisfy hunger, we may safely conclude that there is something wrong in society so when a woman destroys the life of her unborn child, it is an evidence that either by education or circumstances she has been greatly wronged.” Mattie Brinkerhoff, The Revolution, September 2, 1869 SUMMER - FALL 2004 CONTENTS ....... FFL on Campus The Revolution Continues 3 Revolution on Campus 28 The Feminist Case Against Abortion 2004 The history of FFL’s College Outreach Program Serrin Foster’s landmark speech updated 12 Seeds of Change at Georgetown 35 The Other Side How a fresh approach became an annual campus- Abortion advocates struggle to regain lost ground changing event 16 Year-Round Student Activism In Every Issue: A simple plan to transform your campus 38 Herstory 27 Voices of Women Who Mourn 20 Against the Grain 39 We Remember A day in the life of Serrin Foster The quarterly magazine of Feminists for Life of America Editor Cat Clark Editorial Board Nicole Callahan, Laura Ciampa, Elise Ehrhard, Valerie Meehan Schmalz, Maureen O’Connor, Molly Pannell Copy Editors Donna R. Foster, Linda Frommer, Melissa Hunter-Kilmer, Coleen MacKay Production Coordinator Cat Clark Creative Director Lisa Toscani Design/Layout Sally A. Winn Feminists for Life of America, 733 15th Street, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20005; 202-737-3352; www.feministsforlife.org. President Serrin M. -

Votes for Women! Celebrating New York’S Suffrage on November 6, 1917, New York State Passed the Referendum for Women’S Suffrage

New York State’s Women’s Suffrage History Votes for Women! Celebrating New York’s Suffrage On November 6, 1917, New York State passed the referendum for women’s suffrage. This victory was an important event for New York State and the nation. Suffrage in New York State signaled that the national passage of women’s suffrage would soon follow, and in August 1920, “Votes for Women” were constitutionally guaranteed. Although women began asserting their independence long before, the irst coordinated work for women’s suffrage began at the Seneca Falls convention in 1848. The convention served as a catalyst for debates and action. Women like Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage organized and rallied for support of women’s suffrage throughout upstate New York. Others, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer supported the effort through the use of their pens. Stanton wrote letters, speeches, and articles while Bloomer published the irst newspaper for women, The Lily, in 1849. These combined efforts culminated in the creation of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). By the dawn of the twentieth century, the political and social landscape was much different in New York State than ifty years before. The state experienced dramatic advances in industry and urban growth. Several large waves of immigrants settled throughout the state and now more and more women were working outside of the home. Reformers concerns shifted to labor issues, health care, and temperance. New reformers like Harriot Stanton Blatch and Carrie Chapman Catt used new tactics such as marches, meetings, and signed petitions to show that New Yorkers wanted suffrage. -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

Lesley College Current Special Collections and Archives

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Lesley College Current Special Collections and Archives 7-1973 Lesley College Current (July-August 1973) Lesley College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/lesley_current Recommended Citation Lesley College, "Lesley College Current (July-August 1973)" (1973). Lesley College Current. 11. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/lesley_current/11 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and Archives at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lesley College Current by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ···y-Augu.. ·n URRE NT LESLEY COLLEGE THE LESLEY/SUMMERTHING JAMBOREE- STORY PAGE 3 Feminists from 27 countries met at Lesley College from june 1 to june 4 for the first International Feminist Planning Conference, spon sored by the National Organization for Women. Betty Friedan, the nationally known feminist and author of Th e Feminine Mystique, outlined the theme of the conference in the following opening re marks. BETTY FRIEDAN This is a momentous day in the massive unfinished revolution of women of the world toward full equality, human dignity, individual freedom, our own identity in the family of man . In SPEAKS AT every continent, these past ten years women have begun mov ing with accelerating speed against the barriers that have kept LESLEY them from participation in the mainstream of their own society, breaking through the feminine mystique to assert their own personhood and to demand a voice in all the decisions that affect their lives and shape their future. Those decisions up until very recently have been made mainly, almost entirely, by men - in every country, not only the large decisions of war and peace and the government of cities- but even the control of wom en's own bodies, the decision to bear a child, the medical access to birth control and abortion. -

Recommend Reading List & Online Resources

Recommended Reading and Online Resources Related to American Women's Suffrage Compiled by Michelle Marchetti Coughlin, 2020 Mass Humanities Project Scholar, Discussion Series on Women's Suffrage, Falmouth Museums on the Green, 8/05/2020 Michelle Marchetti Coughlin is a historian of early American women and the author of One Colonial Woman's World: The Life and Writings of Mehetabel Chandler Coit and Penelope Winslow, Plymouth Colony First Lady: Re-Imagining a Life. She is currently at work on a book on the wives of the colonial governors ("The First First Ladies"). She serves on the board of the Abigail Adams Birthplace and as Museum Administrator of Boston's Gibson House Museum, and recently guest-curated Pilgrim Hall Museum's "pathFOUNDERS: Women of Plymouth" exhibit. She maintains a website at www.onecolonialwomansworld.com. READING LIST Most of these titles are available through the Cape Cod library system (CLAMS). Jean H. Baker: Sisters: The Lives of America's Suffragists (2005) Barbara F. Berenson: Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement: Revolutionary Reformers (2018) Cathleen D. Cahill: Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement (Nov. 2020) Tina Cassidy: Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait? Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote (2019) Ellen Carol DuBois, ed. The Elizabeth Cady Stanton—Susan B. Anthony Reader: Correspondence, Writings, Speeches (1992) Ellen Carol DuBois: Suffrage: Women's Long Battle for the Vote (2020) Carol Faulkner: Lucretia Mott's Heresy: Abolition and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (2011) Corinne T. Field: The Struggle for Equal Adulthood: Gender, Race, Age, and the Fight for Citizenship in Antebellum America (2014) Jessica D.