The Politics of Voter Fraud by Lorraine C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capital Area Transportation Authority Board of Directors Meeting

CAPITAL AREA TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2018 4:00 P.M. - CATA ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE BUILDING AGENDA I. CALL TO ORDER II. PUBLIC COMMENTS & CORRESPONDENCE TO THE BOARD III. CHAIR'S COMMENTS • Nominating Committee • Strategic Planning Committee • Policy Committee IV. CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER'S REPORT V. ACTION ITEMS - PROPOSED CONSENT AGENDA A. APPROVAL OF MINUTES OF AUGUST 15, 2018, BOARD MEETING B. APPROVAL OF TREASURER'S REPORT FOR AUGUST 2018 1. Interim Income Statement 2. Cash Summary 3. Investments 4. Fifth Third Investment Account Reconciliation e. LEGAL COUNSEL RECOMMENDATION PROPOSED MOTION: That the CATA Board of Directors approve the following law firms to represent CATA during FY 2018-2019: Bleakley, Cypher, Parent, Warren & Quinn, P.e.; George Brookover, P.e.; Dickinson Wright, P.L.L.e.; Murphy & Spagnuolo, P.e.; and Miller Johnson Attorneys. D. CATA BOARD MEETING SCHEDULE FOR FY 2018-2019 PROPOSED MOTION: That the proposed CATA Board Meeting Schedule for FY 2018-2019 be adopted as presented. E. FINANCIAL AUTHORITY RESOLUTION PROPOSED MOTION: That the CATA Board of Directors adopts the Resolution set forth below: Page 1 of 3 RESOLUTION OF BOARD OF DIRECTORS WHEREAS, it is necessary for the Capital Area Transportation Authority, a public transportation authority established under 1963 PA 55 ("CATA"), to utilize banking and investment services for the operation of its business. NOW THEREFORE, be it resolved that: 1. CATA's Chief Executive Officer is hereby authorized to execute agreements with Fifth Third Bank and other financial institutions as the Chief Executive Officer deems necessary to provide banking and investment services for an indefinite period, effective on and after September 19, 2018; 2. -

Local Election Act;

1 AN ACT 2 RELATING TO ELECTIONS; ENACTING THE LOCAL ELECTION ACT; 3 PROVIDING FOR A SINGLE ELECTION DAY AND UNIFORM PROCESSES FOR 4 CERTAIN LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS; PROVIDING THAT CERTAIN 5 BALLOT MEASURE ELECTIONS THAT ARE HELD AT TIMES OTHER THAN 6 WITH REGULAR LOCAL ELECTIONS ONLY BE CONDUCTED BY MAILED 7 BALLOT; REQUIRING SPECIAL STATEWIDE BALLOT QUESTION ELECTIONS 8 TO BE CONDUCTED BY MAILED BALLOT; PROHIBITING ADVISORY 9 QUESTIONS ON THE BALLOT; UPDATING CIRCUMSTANCES CAUSING A 10 VACANCY IN LOCAL OFFICE; NAMING CHAPTER 1, ARTICLE 24 NMSA 11 1978 THE "SPECIAL ELECTION ACT"; CHANGING THE LIMITS ON SOIL 12 AND WATER CONSERVATION LEVIES; REPEALING THE SCHOOL ELECTION 13 LAW, THE MAIL BALLOT ELECTION ACT, THE MUNICIPAL ELECTION 14 CODE AND OTHER PROVISIONS OF LAW IN CONFLICT WITH THE LOCAL 15 ELECTION ACT; MAKING CONFORMING AMENDMENTS TO OTHER SECTIONS 16 OF LAW; MAKING AN APPROPRIATION. 17 18 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO: 19 SECTION 1. Section 1-1-19 NMSA 1978 (being Laws 1969, 20 Chapter 240, Section 19, as amended) is amended to read: 21 "1-1-19. ELECTIONS COVERED BY CODE.-- 22 A. The Election Code applies to the following: 23 (1) general elections; 24 (2) primary elections; 25 (3) special elections; HLELC/HB 98 Page 1 1 (4) elections to fill vacancies in the 2 office of United States representative; 3 (5) local elections included in the Local 4 Election Act; and 5 (6) recall elections of county officers, 6 school board members or applicable municipal officers. 7 B. -

Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence Of

Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Elections are essential elements of democratic systems. Unfortunately, abuse and manipulation (including voter intimidation, vote buying or ballot stuffing) can distort these processes. However, little attention has been paid to an intrinsic part of this threat: the conditions and opportunities for criminal interference in the electoral process. Most worrying, few scholars have examined the underlying conditions that make elections vulnerable to organized criminal involvement. This report addresses these gaps in knowledge by analysing the vulnerabilities of electoral processes to illicit interference (above all by organized crime). It suggests how national and international authorities might better protect these crucial and coveted elements of the democratic process. Case studies from Georgia, Mali and Mexico illustrate these challenges and provide insights into potential ways to prevent and mitigate the effects of organized crime on elections. International IDEA Clingendael Institute ISBN 978-91-7671-069-2 Strömsborg P.O. Box 93080 SE-103 34 Stockholm 2509 AB The Hague Sweden The Netherlands T +46 8 698 37 00 T +31 70 324 53 84 F +46 8 20 24 22 F +31 70 328 20 02 9 789176 710692 > [email protected] [email protected] www.idea.int www.clingendael.nl ISBN: 978-91-7671-069-2 Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Series editor: Catalina Uribe Burcher Lead authors: Ivan Briscoe and Diana Goff © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance © 2016 Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael Institute) International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int Clingendael Institute P.O. -

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations May 21, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45733 SUMMARY R45733 Combating Corruption in Latin America May 21, 2019 Corruption of public officials in Latin America continues to be a prominent political concern. In the past few years, 11 presidents and former presidents in Latin America have been forced from June S. Beittel, office, jailed, or are under investigation for corruption. As in previous years, Transparency Coordinator International’s Corruption Perceptions Index covering 2018 found that the majority of Analyst in Latin American respondents in several Latin American nations believed that corruption was increasing. Several Affairs analysts have suggested that heightened awareness of corruption in Latin America may be due to several possible factors: the growing use of social media to reveal violations and mobilize Peter J. Meyer citizens, greater media and investor scrutiny, or, in some cases, judicial and legislative Specialist in Latin investigations. Moreover, as expectations for good government tend to rise with greater American Affairs affluence, the expanding middle class in Latin America has sought more integrity from its politicians. U.S. congressional interest in addressing corruption comes at a time of this heightened rejection of corruption in public office across several Latin American and Caribbean Clare Ribando Seelke countries. Specialist in Latin American Affairs Whether or not the perception that corruption is increasing is accurate, it is nevertheless fueling civil society efforts to combat corrupt behavior and demand greater accountability. Voter Maureen Taft-Morales discontent and outright indignation has focused on bribery and the economic consequences of Specialist in Latin official corruption, diminished public services, and the link of public corruption to organized American Affairs crime and criminal impunity. -

The Truth About Voter Fraud 7 Clerical Or Typographical Errors 7 Bad “Matching” 8 Jumping to Conclusions 9 Voter Mistakes 11 VI

Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A sin- gular institution—part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group—the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S VOTING RIGHTS AND ELECTIONS PROJECT The Voting Rights and Elections Project works to expand the franchise, to make it as simple as possible for every eligible American to vote, and to ensure that every vote cast is accurately recorded and counted. The Center’s staff provides top-flight legal and policy assistance on a broad range of election administration issues, including voter registration systems, voting technology, voter identification, statewide voter registration list maintenance, and provisional ballots. © 2007. This paper is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-No Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org). It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is credited, a link to the Center’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The paper may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Center’s permission. -

Disinformation in Democracies: Strengthening Digital Resilience in Latin America

Atlantic Council ADRIENNE ARSHT LATIN AMERICA CENTER Disinformation in Democracies: Strengthening Digital Resilience in Latin America The Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center broadens understanding of regional transformations through high-impact work that shapes the conversation among policymakers, the business community, and civil society. The Center focuses on Latin America’s strategic role in a global context with a priority on pressing political, economic, and social issues that will define the trajectory of the region now and in the years ahead. Select lines of programming include: Venezuela’s crisis; Mexico-US and global ties; China in Latin America; Colombia’s future; a changing Brazil; Central America’s trajectory; combatting disinformation; shifting trade patterns; and leveraging energy resources. Jason Marczak serves as Center Director. The Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) is at the forefront of open-source reporting and tracking events related to security, democracy, technology, and where each intersect as they occur. A new model of expertise adapted for impact and real-world results, coupled with efforts to build a global community of #DigitalSherlocks and teach public skills to identify and expose attempts to pollute the information space, DFRLab has operationalized the study of disinformation to forge digital resilience as humans are more connected than at any point in history. For more information, please visit www.AtlanticCouncil.org. This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. -

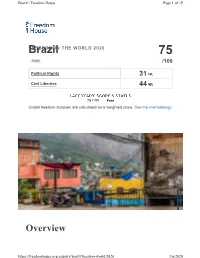

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

2021 Regular Local Election Candidate Guide Here

2021 Regular Local Election Candidate Guide Version 2.0 – Published August 4, 2021 2021 Candidate Information Guide Revision History Version Updates Editor Date 1.1 Updates to list of Alexis Levy 5.25.2021 municipalities participating in RLE 2.0 Updates to list of Lauren Hutchison, Lee Ann 8.4.2021 Municipalities Lopez, Charles Romero participating in RLE; minor text, spelling and grammar updates 2 About This Guide This publication, prepared by the Office of the New Mexico Secretary of State, Bureau of Elections, serves as an easy-to-use reference for candidates seeking office in the 2021 Regular Local Election, and for anyone interested in the election process in New Mexico. Please note, this guide is intended merely as a reference, not as a legal authority. This guide does not supersede federal or state laws or rules, and it does not have the force of law. Please always consult the local government’s specific governing statute, charter, or ordinance for the specific requirements to hold elected office. Copies of the New Mexico Election Code and other applicable laws are available in the 2021 Election Handbook of the State of New Mexico, published on our website www.sos.state.nm.us. If you have any questions about this guide’s information or if you have questions regarding elections that are not provided for in this guide, please feel free to call the Bureau of Elections at 1 -800-477-3632 or (505) 827-3600, or email [email protected]. 3 Table of Contents 2021 Candidate Information Guide ............................................................................................................. 2 Revision History ........................................................................................................................................ -

Candidate's Guide to Local Elections in B.C

CANDIDATE’S GUIDE TO LOCAL ELECTIONS IN B.C. 2018 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: Candidate’s Guide to Local Elections in B.C. Available also on the internet. Running title: Local elections candidate’s guide. Previously published: Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, 2018 ISBN 0-7726-5431-X 1. Local elections - British Columbia. 2. Election law - British Columbia. 3. Campaign funds - Law and legislation - British Columbia. 4. Political campaigns - Law and legislation - British Columbia. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Municipal Affairs. II. Title: Local election candidate’s guide KEB478.5.E43C36 2005 324.711’07 C2005-960198-1 KF4483.E4C36 2005 Table of Contents Key Contacts iii Conflict of Interest and Other Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing iii Ethical Standards 11 Elections BC iii Disclosure of Conflict 11 Ministry of Education iii Inside Influence 12 Enquiry BC iv Outside Influence 12 Municipal and Regional Accepting Gifts 12 District Information iv Disclosure of Contracts 12 Use of Insider Information 12 Other Resources v Voting for an Illegal Expenditure 12 BC Laws v Consequences 12 Elections Legislation v Confidentiality 12 Educational Materials v Elected Officials and Local Disclaimer vi Government Staff 14 New Elections Legislation – Shared Roles Qualifications 15 and Responsibilities 1 Who May Run for Office 15 Local Government Employees 15 Introduction 3 Local Government Contractors 15 Local Elections Generally 5 B.C. Public Service Employees 15 Voting Opportunities -

Corruption Perceptions Index 2020

CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2020 Transparency International is a global movement with one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. With more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we are leading the fight against corruption to turn this vision into reality. #cpi2020 www.transparency.org/cpi Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of January 2021. Nevertheless, Transparency International cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. ISBN: 978-3-96076-157-0 2021 Transparency International. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-ND 4.0 DE. Quotation permitted. Please contact Transparency International – [email protected] – regarding derivatives requests. CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX 2020 2-3 12-13 20-21 Map and results Americas Sub-Saharan Africa Peru Malawi 4-5 Honduras Zambia Executive summary Recommendations 14-15 22-23 Asia Pacific Western Europe and TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE European Union 6-7 Vanuatu Myanmar Malta Global highlights Poland 8-10 16-17 Eastern Europe & 24 COVID-19 and Central Asia Methodology corruption Serbia Health expenditure Belarus Democratic backsliding 25 Endnotes 11 18-19 Middle East & North Regional highlights Africa Lebanon Morocco TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL 180 COUNTRIES. 180 SCORES. HOW DOES YOUR COUNTRY MEASURE UP? -

Indiana Referenda and Primary Election Materials

:::: DISCLAIMER :::: The following document was uploaded by ballotpedia.org staff with the written permission of the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research for non-commercial use only. It is not intended for redistribution. For information on rights and usage of this file, please contact: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 www.icpsr.umich.edu For general information on rights and usage of Ballotpedia content, please contact: [email protected] ICPSR Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research Referenda and Primary Election Materials Part 12: Referenda Elections for Indiana Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research ICPSR 0006 This document was previously available in paper format only. It was converted to Portable Document Format (PDF), with no manual editing, on the date below as part of ICPSR's electronic document conversion project. The document may not be completely searchable. No additional updating of this collection has been performed (pagination, missing pages, etc.). June 2002 ICPSR Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research Referenda and Primary Election Materials Part 12: Referenda Elections for Indiana Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research ICPSR 0006 REFERENDAAND PRIMARY ELECTION MATERIALS (ICPSR 0006) Principal Investigator Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research P.O. Box 1248 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 BIBLIOGRAPHIC CITATION Publications based on ICPSR data collections should acknowledge those sources by means of bibliographic citations. To ensure that such source attributions are captured for social science bibliographic utilities, citations must appear in footnotes or in the reference section of publications. -

Turning the Tide on Dirty Money Why the World’S Democracies Need a Global Kleptocracy Initiative

GETTY IMAGES Turning the Tide on Dirty Money Why the World’s Democracies Need a Global Kleptocracy Initiative By Trevor Sutton and Ben Judah February 2021 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Contents 1 Preface 3 Introduction and summary 6 How dirty money went global and why efforts to stop it have failed 10 Why illicit finance and kleptocracy are a threat to global democracy and should be a foreign policy priority 13 The case for optimism: Why democracies have a structural advantage against kleptocracy 18 How to harden democratic defenses against kleptocracy: Key principles and areas for improvement 21 Recommendations 28 Conclusion 29 Corruption and kleptocracy: Key definitions and concepts 31 About the authors and acknowledgments 32 Endnotes Preface Transparency and honest government are the lifeblood of democracy. Trust in democratic institutions depends on the integrity of public servants, who are expected to put the common good before their own interests and faithfully observe the law. When officials violate that duty, democracy is at risk. No country is immune to corruption. As representatives of three important democratic societies—the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom—we recognize that corruption is an affront to our shared values, one that threatens the resiliency and cohesion of democratic governments around the globe and undermines the relationship between the state and its citizens. For that reason, we welcome the central recommendation of this report that the world’s democracies should work together to increase transparency in the global economy and limit the pernicious influence of corruption, kleptocracy, and illicit finance on democratic institutions.