Disinformation in Democracies: Strengthening Digital Resilience in Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entre Os Dias 1º. E 7 De Junho De 2020, Foram Observados 17.191 Posts Nas 719 Páginas De Nossa Amostra, Que Geraram 10.230.467 Compartilhamentos

Semana 99 – De 1° a 7 de junho de 2020 Entre os dias 1º. e 7 de junho de 2020, foram observados 17.191 posts nas 719 páginas de nossa amostra, que geraram 10.230.467 compartilhamentos. Os principais recursos utilizados nos posts foram fotos (39%), links (37%), vídeos (23%) e texto (1%). A extrema direita segue protagonizando o debate político no Facebook, instrumentalizando a plataforma para defender o presidente Jair Bolsonaro (sem partido) e atacar todos aqueles que considera opositores do governo. Essa categoria cresce e se diversifica a cada dia, abrangendo setores e políticos que vão da esquerda à própria extrema direita. Somam-se aos alvos costumeiros (a imprensa, o PT, Lula, Dilma, o STF, Cuba e Venezuela), os governadores e prefeitos que adotaram a quarentena pelo país - sobretudo João Dória (PSDB-SP) e Wilson Witzel (PSC-RJ) -, a deputada Joice Hasselmann (PSL-SP), os/as gays, as feministas e os militantes do movimento antifascista. Nuvem de palavras Contudo, novos atores têm pautado as discussões e o discurso foi progressivamente radicalizado, inclu- sive com o uso mais frequentes de palavras de baixo calão. Destaca-se a atuação da deputada Carla Zambelli (PSL-SP), que responde por 12 dos 20 posts mais compartilhados do período e acumulou mais de 700 mil comparti- lhamentos durante a semana. O post mais compartilhado da semana (114.276) é um vídeo no qual o deputado federal André Janones (AVANTE-MG) apoia o veto de Jair Bolsonaro ao repasse de R$8 bilhões aos estados e municípios, afirmando que essas esferas não necessitam do dinheiro pois não sabem administrar seus recursos e desviam verbas desti- nadas ao combate da Covid-19. -

Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence Of

Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Elections are essential elements of democratic systems. Unfortunately, abuse and manipulation (including voter intimidation, vote buying or ballot stuffing) can distort these processes. However, little attention has been paid to an intrinsic part of this threat: the conditions and opportunities for criminal interference in the electoral process. Most worrying, few scholars have examined the underlying conditions that make elections vulnerable to organized criminal involvement. This report addresses these gaps in knowledge by analysing the vulnerabilities of electoral processes to illicit interference (above all by organized crime). It suggests how national and international authorities might better protect these crucial and coveted elements of the democratic process. Case studies from Georgia, Mali and Mexico illustrate these challenges and provide insights into potential ways to prevent and mitigate the effects of organized crime on elections. International IDEA Clingendael Institute ISBN 978-91-7671-069-2 Strömsborg P.O. Box 93080 SE-103 34 Stockholm 2509 AB The Hague Sweden The Netherlands T +46 8 698 37 00 T +31 70 324 53 84 F +46 8 20 24 22 F +31 70 328 20 02 9 789176 710692 > [email protected] [email protected] www.idea.int www.clingendael.nl ISBN: 978-91-7671-069-2 Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Series editor: Catalina Uribe Burcher Lead authors: Ivan Briscoe and Diana Goff © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance © 2016 Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael Institute) International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int Clingendael Institute P.O. -

Central America Economic Reactivation in a COVID-19 World: FINDING SUSTAINABLE OPPORTUNITIES in UNCERTAIN TIMES

Atlantic Council ADRIENNE ARSHT LATIN AMERICA CENTER Central America Economic Reactivation in a COVID-19 World: FINDING SUSTAINABLE OPPORTUNITIES IN UNCERTAIN TIMES By: María Eugenia Brizuela de Ávila, Laura Chinchilla Miranda, María Fernanda Bozmoski, and Domingo Sadurní Contributing authors: Enrique Bolaños and Salvador Paiz The Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center broadens understanding of regional transformations through high-impact work that shapes the conversation among policymakers, the business community, and civil society. The Center focuses on Latin America’s strategic role in a global context with a priority on pressing political, economic, and social issues that will define the trajectory of the region now and in the years ahead. Select lines of programming include: Venezuela’s crisis; Mexico-US and global ties; China in Latin America; Colombia’s future; a changing Brazil; Central America’s trajectory; Caribbean development; commercial patterns shifts; energy resources; and disinformation. Jason Marczak serves as Center Director. For more information, please visit www.AtlanticCouncil.org. This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. © 2020 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or -

The Week in Review on the ECONOMIC FRONT GDP: the Brazilian Statistics Agency (IBGE) Announced That GDP Growth for the Second Quarter Totaled 1.5%

POLICY MONITOR August 26 – 30 , 2013 The Week in Review ON THE ECONOMIC FRONT GDP: The Brazilian Statistics Agency (IBGE) announced that GDP growth for the second quarter totaled 1.5%. This year, GDP grew by 2.1%. Interest Rate: The Monetary Policy Committee (COPOM) of the Central Bank unanimously decided to raise interest rates by 0.5% to 9%--the fourth increase in a row. The Committee will hold two more meetings this year. Market analysts expect interest rates to rise by at least one more point to 10%. Strikes: Numerous groups of workers are under negotiations with the government for salary adjustments. Among those are regulatory agencies, national transportation department (DNIT), and livestock inspectors. DNIT workers have been on strike since June and livestock inspectors begun their strike on Thursday. On Friday, union workers will hold demonstrations throughout the country. Tourism: A study conducted by the Ministry of Tourism showed that the greatest cause of discontent for tourists coming to Brazil was high prices. The second most important reason was telecommunication services. Airport infrastructure, safety, and public transportation did not bother tourists as much and were ranked below both issues. Credit Protection: The Agency for Credit Protection Services (SPC Brasil) announced that the largest defaulting groups are in the middle class (Brazilian Class C). Forty-seven percent of all defaults are within Class C, 34% in Class B, and 13% in Class D. Forty-six percent of respondents claim to have been added to the list of default due to credit card payment delays and 40% due to bank loans. -

Covid-19 and the Brazilian 2020 Municipal Elections

Covid-19 and the Brazilian 2020 Municipal Elections Case Study, 19 February 2021 Gabriela Tarouco © 2021 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/>. International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm Sweden Telephone: +46 8 698 37 00 Email: [email protected] Website: <https://www.idea.int> Editor: Andrew Robertson This case study is part of a collaborative project between the Electoral Management Network <http:// www.electoralmanagement.com> and International IDEA, edited by Toby S. James (University of East Anglia), Alistair Clark (Newcastle University) and Erik Asplund (International IDEA). Created with Booktype: <https://www.booktype.pro> International IDEA Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... -

Chapter 2. Public Security in Central America Laura Chinchilla Miranda

Chapter 2. Public Security in Central America Laura Chinchilla Miranda This chapter analyzes the problem of public security in Central America—Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica—from 1980 to 2000. It begins by presenting the changes in the sub-region’s security agenda, characterized by the discontinuance of the “national security” notion and the adoption of the concept of “public security” or “citizen security.” Both concepts have significant implications for the definition of threats, the types of responses that threats trigger, and the institutional players that intervene. The chapter goes on to describe the Central American security problem, characterized by increasing crime rates—especially for violent crimes—and an intensification of the population’s feeling of insecurity. Next, it analyzes the institutional responses to crime and violence that the countries of the region have coordinated. During the past two decades, Central America encouraged a dynamic process of strengthening civilian police forces and establishing a criminal justice administration that would be more consistent with the democratic context and new social requirements. These internal reform processes have been matched by region-wide efforts seeking to improve the level of coordination among law-enforcement authorities in combating organized crime. However, the chapter points out that such efforts have not generated the anticipated public response, and this has resulted in dangerous trends toward a return to repressive reactions that threaten the still nascent democratic processes of the region. 1 The final section presents some alternative concepts that are gaining acceptance in the region’s public security agendas, such as community security and democratic security. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Revista de Investigações Constitucionais ISSN: 2359-5639 Universidade Federal do Paraná KATZ, ANDREA SCOSERIA Making Brazil work? Brazilian coalitional presidentialism at 30 and its post-Lava Jato prospects Revista de Investigações Constitucionais, vol. 5, no. 3, 2018, September-December, pp. 77-102 Universidade Federal do Paraná DOI: https://doi.org/10.5380/rinc.v5i3.60965 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=534063442006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Licenciado sob uma Licença Creative Commons Licensed under Creative Commons Revista de Investigações Constitucionais ISSN 2359-5639 DOI: 10.5380/rinc.v5i3.60965 Making Brazil work? Brazilian coalitional presidentialism at 30 and its post-Lava Jato prospects Fazendo o Brasil funcionar? O presidencialismo de coalizão brasileiro aos seus 30 anos e suas perspectivas pós-Lava Jato ANDREA SCOSERIA KATZI, * I Yale University (United States of America) [email protected] Recebido/Received: 12.08.2018 / August 12th, 2018 Aprovado/Approved: 03.09.2018 / September 03rd, 2018 Abstract Resumo This article analyzes the topic of Brazilian coalition pres- O artigo analisa a questão do presidencialismo de coalizão identialism. It offers the reader a close look at coalitional nos países da América Latina em geral e no Brasil em parti- presidentialism in each of Brazil’s governments since the cular. Oferece ao leitor um olhar mais atento ao presiden- democratization of the country to the present day, pre- cialismo de coalizão em todos os governos brasileiros desde senting the complex relations between the Legislative a democratização do país até os dias atuais, apresentando Branch and the Executive Branch at these different mo- as complexas relações entre o Poder Legislativo e o Poder ments in Brazil’s political history. -

International Court of Justice

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE DISPUTE CONCERNING CERTAIN ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT BY NICARAGUA IN THE BORDER AREA (COSTA RICA V. NICARAGUA) COUNTER - MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF NICARAGUA VOLUME III (ANNEXES FROM 27 TO 111) 06 August 2012 LIST OF ANNEXES VOLUME III Annex Page No. LAWS, DECREES, ADMINISTRATIVE RESOLUTIONS AND REGULATIONS 27 Excerpts of the Political Constitution of the Republic of Nicaragua. 1 28 Nicaraguan Decree No. 45-94, 28 October 1994. 5 29 Nicaraguan Law No. 217, 6 June 1996. 13 30 Excerpt of “Dictamen Juridico 351, (C-351-2006), Mauricio Castro 39 Lizano, Deputy Attorney General (Procurador Adjunto)”, 31 August 2006 (1). Excerpt of “Northern Channels (Tortuguero)” (2). 31 Nicaraguan Decree No. 01-2007, Regulation of Protected Areas in 47 Nicaragua, 8 January 2007. 32 Nicaraguan Law No. 647, 3 April 2008. 71 33 MARENA Administrative Resolution No. 038-2008, 22 December 77 2008. 34 Ministry for the Environment and Natural Resources (MARENA) 89 Administrative Resolution No. 038-2008-A1, 30 October 2009. 35 Official Daily Gazette No. 46, Decree No. 36440-MP,Year CXXXIII. 95 La Uruca, San José, Costa Rica, 7 March 2011 (1). By-laws and regulations, Presidency of the Republic, National Commission on Risk Prevention and Attention to Emergencies, Decision No. 0362-2011, Specific By-Laws regarding purchasing and contracts procedures under exception mechanisms regime by virtue of the Declaration of a State of Emergency by virtue of Decree No. 36440, 21 September 2011 (2). iii MILITARY DOCUMENTS 36 Order n° 005 from the Chief of the South Military Detachment for 107 compliance of order from the Chief of staff regarding the implementation of special measures based on provisional measures of protection ordered by the International Court of Justice and maintenance of the anti-drug trafficking plan, rural, security plan and presidential Decree 79/2009 at the San Juan de Nicaragua directorate, 9 March 2011. -

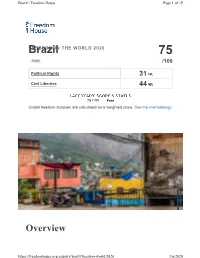

Freedom in the World Report 2020

Brazil | Freedom House Page 1 of 19 BrazilFREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 75 FREE /100 Political Rights 31 Civil Liberties 44 75 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview https://freedomhouse.org/country/brazil/freedom-world/2020 3/6/2020 Brazil | Freedom House Page 2 of 19 Brazil is a democracy that holds competitive elections, and the political arena is characterized by vibrant public debate. However, independent journalists and civil society activists risk harassment and violent attack, and the government has struggled to address high rates of violent crime and disproportionate violence against and economic exclusion of minorities. Corruption is endemic at top levels, contributing to widespread disillusionment with traditional political parties. Societal discrimination and violence against LGBT+ people remains a serious problem. Key Developments in 2019 • In June, revelations emerged that Justice Minister Sérgio Moro, when he had served as a judge, colluded with federal prosecutors by offered advice on how to handle the corruption case against former president Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, who was convicted of those charges in 2017. The Supreme Court later ruled that defendants could only be imprisoned after all appeals to higher courts had been exhausted, paving the way for Lula’s release from detention in November. • The legislature’s approval of a major pension reform in the fall marked a victory for Brazil’s far-right president, Jair Bolsonaro, who was inaugurated in January after winning the 2018 election. It also signaled a return to the business of governing, following a period in which the executive and legislative branches were preoccupied with major corruption scandals and an impeachment process. -

President Laura Chinchilla Begins Term with Commitment to Safer, Greener, More Prosperous Costa Rica George Rodriguez

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiCen Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 5-13-2010 President Laura Chinchilla Begins Term With Commitment To Safer, Greener, More Prosperous Costa Rica George Rodriguez Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen Recommended Citation Rodriguez, George. "President Laura Chinchilla Begins Term With Commitment To Safer, Greener, More Prosperous Costa Rica." (2010). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen/9788 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiCen by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 50577 ISSN: 1089-1560 President Laura Chinchilla Begins Term With Commitment To Safer, Greener, More Prosperous Costa Rica by George Rodriguez Category/Department: Costa Rica Published: 2010-05-13 "Sí, juro" (Yes, I swear). With those words Laura Chinchilla became the first woman to be sworn into office as president of Costa Rica (NotiCen, February 11, 2010). Minutes later, as this Central American nation's head of state, Chinchilla addressed her fellow Costa Ricans, committing herself to work, among other major goals, for what she successively described as a safer, greener, more prosperous country, one where fruitful, honest dialogue is the name of the game and where no one is entitled to believe they monopolize the truth. Parque Metropolitano La Sabana, on the capital city's west end and one of the town's two major parks, was the site chosen for the event to allow as many people as possible to attend, along with the nine presidents and delegations sent by some 30 governments. -

Baixar Baixar

Exilium Revista de Estudos da Contemporaneidade Créditos institucionais Profa. Dra. Soraya Soubhi Smaili Reitora Prof. Dr. Nelson Sass Vice-Reitor Profa. Dra. Lia Rita Azeredo Bittencourt Pró-Reitora de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa Profa. Dra. Karen Spadari Ferreira Pró-Reitora Adjunta de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa Cátedra Edward Saïd de Estudos Contemporâneos Coordenadora: Olgária Chain Féres Matos Vice-Coordenadora: Cynthia Andersen Sarti Inserção Institucional e composição A Cátedra Edward Saïd está vinculada à Pró-Reitoria de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa da Unifesp Exilium: Revista de Estudos da Contemporaneidade – Periodicidade semestral Editora chefe: Olgária Chain Féres Matos Editora executiva: Maria das Graças de Souza Editores associados: Christiane Damien, Cynthia Andersen Sarti, Javier Amadeo, Jens Baungarten, Leandra Yunis, Thomaz Kawauche Conselho científico: Anselm Jappe (Accademia di Belle Arti di Sassari/Itália), Claudine Haroche (CNRS/França), Edgardo Bechara (Cátedra Edward W. Saïd/Argentina), Edward Alam (Universidade de Notre Dame/Líbano), Francisco Miraglia (USP), Giacomo Marramao (Universidade de Roma III/Itália), Gustavo Lins Ribeiro (UAM-Iztapalapa/México e UnB), Heloisa M. Starling (UFMG), Horacio González (Universidade de Buenos Aires/Argentina), Mamede Mustafa Jarouche (USP), Massimo Canevacci (Universidade de Roma/Itália), Miguel Chaia (PUC-SP), Patrícia Birman (UFRJ), Regina Novaes (UFRJ), Soledad Bianchi (Universidade do Chile/Chile), Maria Teresa Ricci (Université de Tours/França), Youssef Rahme (Universidade de Notre -

Challenges and Opportunities for the Implementation of E-Voting In

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations BEL Bharat Electronics Limited BU Ballot Unit CU Control Unit CVR Continuous Voter Registration ECES European Centre for Electoral Support ECIL Electronics Corporation of India ECI Electoral Commission of India ECN Electoral Commission of Namibia ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States ECONEC Electoral Commission of West African States EMB Electoral Management Bodies e-KTP electronic resident identification card EU-SDGN European Union Support for Democratic Governance in Nigeria EVM Electronic Voting Machine DRE Direct Recording Electronic Voting Machine ICTs Information and Communication Technologies INEC Independent National Electoral Commission KPU Komisi Pemilihan Umum (General Election Commission of Indonesia) PST Public Security Test PSU Public Sector Undertaking PVC Permanent Voter Card REC Resident Electoral Commissioner SADC Southern African Development Community SCR Smart Card Readers SEC Superior Electoral Court SIDALIH Voter Data Information System Technical Guidance TEC Technical Expert Committee VPN Virtual Private Network (VRKs) Voter Registration Kits VVPAT Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 12 1.1 Aim and Objectives .........................................................................................................