About the Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saga Jacques Vabre/P.27-34

PAR JEAN WATIN-AUGOUARD (saga ars, de l’or en barre Mars, ou comment une simple pâte à base de lait, de sucre et d’orge recouverte d’une couche de caramel, le tout enrobé d’une fine couche de chocolat au lait est devenue la première barre chocolatée mondiale et l’un des premiers produits nomades dans l’univers de la confiserie. (la revue des marques - n°46 - avril 2004 - page 27 saga) Franck C. Mars ne reçu jamais le moindre soutien des banques et fit de l’autofinancement une règle d’or, condition de sa liberté de créer. Celle-ci est, aujourd’hui, au nombre des cinq principes du groupe . Franck C. Mars, 1883-1934 1929 - Franck Mars ouvre une usine ultramoderne à Chicago est une planète pour certains, le dieu de la guerre pour d’autres, une confiserie pour tous. Qui suis-je ?… Mars, bien sûr ! Au reste, Mars - la confiserie -, peut avoir les trois sens pour les mêmes C’ personnes ! La planète du plaisir au sein de laquelle trône le dieu Mars, célèbre barre chocolatée dégustée dix millions de fois par jour dans une centaine de pays. Mars, c’est d’abord le patronyme d’une famille aux commandes de la société du même nom depuis quatre générations, société - cas rare dans l’univers des multinationales -, non côtée en Bourse. Tri des œufs S’il revient à la deuxième génération d’inscrire la marque au firmament des réussites industrielles et commerciales exemplaires, et à la troisième de conquérir le monde, la première génération peut se glorifier d’être à l’origine d’une recette promise à un beau succès. -

Mars 2015 Brochure.Pdf

Welcome 2014 has been a bumper year and here at Mars® Ice Cream we are incredibly proud of our continued focus delivering more fantastic results. Over the past two years Mars® Ice Cream has grown an exceptional 18% and with our plans for the future we are certain to keep this success going! We strive to keep offering consumers the unique taste and experience of the Nations’ Favourite Chocolate Brands in Ice Cream; including Mars®, Snickers®, Maltesers®, Galaxy®, Bounty®, Twix® and M&M’s® and our 2015 initiatives are sure to do just that. We’re launching our 1 in 6 on pack promotion which will give consumers a chance to instantly win more of the delicious Ice Cream they love, driving increased penetration for our brands. We are dedicated to meeting the ever changing needs of consumers and so continue to build and reformulate our portfolio. In 2015 we’re launching an exciting new product on our biggest brand Galaxy®; an Ice Cream Bar designed to offer consumers a more permissible and affordable treat. We’re also bringing out new even tastier recipes for both Twix® and Bounty®. Our aim continues to be to offer you choice within your Ice Cream range; to enable you to service more consumers and to ensure you maximise your season with our continued support and service. We’re committed to Quality Ice Cream Introducing our Ice Cream team We’re the only confectionery company with our own Ice Cream factory. Our core recipes use real milk and cream. Our range is free from artificial additives, preservatives, flavours and colours. -

The History of Women in Jazz in Britain

The history of jazz in Britain has been scrutinised in notable publications including Parsonage (2005) The Evolution of Jazz in Britain, 1880-1935 , McKay (2005) Circular Breathing: The Cultural Politics of Jazz in Britain , Simons (2006) Black British Swing and Moore (forthcoming 2007) Inside British Jazz . This body of literature provides a useful basis for specific consideration of the role of women in British jazz. This area is almost completely unresearched but notable exceptions to this trend include Jen Wilson’s work (in her dissertation entitled Syncopated Ladies: British Jazzwomen 1880-1995 and their Influence on Popular Culture ) and George McKay’s chapter ‘From “Male Music” to Feminist Improvising’ in Circular Breathing . Therefore, this chapter will provide a necessarily selective overview of British women in jazz, and offer some limited exploration of the critical issues raised. It is hoped that this will provide a stimulus for more detailed research in the future. Any consideration of this topic must necessarily foreground Ivy Benson 1, who played a fundamental role in encouraging and inspiring female jazz musicians in Britain through her various ‘all-girl’ bands. Benson was born in Yorkshire in 1913 and learned the piano from the age of five. She was something of a child prodigy, performing on Children’s Hour for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) at the age of nine. She also appeared under the name of ‘Baby Benson’ at Working Men’s Clubs (private social clubs founded in the nineteenth century in industrial areas of Great Britain, particularly in the North, with the aim of providing recreation and education for working class men and their families). -

Non-Wood Forest Products from Conifers

Page 1 of 8 NON -WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS 12 Non-Wood Forest Products From Conifers FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-37 ISBN 92-5-104212-8 (c) FAO 1995 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABBREVIATIONS INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1 - AN OVERVIEW OF THE CONIFERS WHAT ARE CONIFERS? DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE USES CHAPTER 2 - CONIFERS IN HUMAN CULTURE FOLKLORE AND MYTHOLOGY RELIGION POLITICAL SYMBOLS ART CHAPTER 3 - WHOLE TREES LANDSCAPE AND ORNAMENTAL TREES Page 2 of 8 Historical aspects Benefits Species Uses Foliage effect Specimen and character trees Shelter, screening and backcloth plantings Hedges CHRISTMAS TREES Historical aspects Species Abies spp Picea spp Pinus spp Pseudotsuga menziesii Other species Production and trade BONSAI Historical aspects Bonsai as an art form Bonsai cultivation Species Current status TOPIARY CONIFERS AS HOUSE PLANTS CHAPTER 4 - FOLIAGE EVERGREEN BOUGHS Uses Species Harvesting, management and trade PINE NEEDLES Mulch Decorative baskets OTHER USES OF CONIFER FOLIAGE CHAPTER 5 - BARK AND ROOTS TRADITIONAL USES Inner bark as food Medicinal uses Natural dyes Other uses TAXOL Description and uses Harvesting methods Alternative -

Mars Wrigley Catalogue 2019

PRODUCT CATALOGUE MARS® Bar 53g MARS® Bar 2 Pak 72g Original Original Units Per Outer 48 Units Per Outer 24 REC RETAIL $1.95 REC RETAIL $2.29 NEW NEW MARS® Bar 53g MARS® Bar 2 Pak 72g Choc Loaded Choc Loaded Units Per Outer 24 Units Per Outer 24 REC RETAIL $1.95 REC RETAIL $2.29 SNICKERS® Bar 50g SNICKERS® Bar 2 Pack 72g Units Per Outer 48 Units Per Outer 24 REC RETAIL $1.95 REC RETAIL $2.29 NEW NEW SNICKERS® Bar 50g SNICKERS® Bar 2 Pack 72g Almond Almond Units Per Outer 24 Units Per Outer 24 REC RETAIL $1.95 REC RETAIL $2.29 BOUNTY® 56g BOUNTY® 3 Pak 84g Units Per Outer 24 Units Per Outer 21 REC RETAIL $1.95 REC RETAIL $2.29 Page 2 of 24 | Mars Wrigley Confectionery | Product Catalogue PRODUCT CATALOGUE MILKYWAY® Bar 25g MILKYWAY® 2 Pak 53g Units per outer 42 Units per outer 24 REC RETAIL 69¢ REC RETAIL $1.95 TWIX® Bar 50g TWIX® Xtra 2 Pak 72g Original Original Units Per Outer 20 Units per outer 20 REC RETAIL $1.95 REC RETAIL $2.29 A Little Bit of... A Little Bit of... MARS® Bars 18g SNICKERS® Bars 18g Units Per Outer 50 Units Per Outer 50 REC RETAIL 69¢ REC RETAIL 69¢ A Little Bit of... A Little Bit of... TWIX® Bars 14.5g MALTESERS® Bars 12g Units Per Outer 50 Units Per Outer 40 REC RETAIL 69¢ REC RETAIL 69¢ Mars Wrigley Confectionery | Product Catalogue | Page 3 of 24 MARS® 216g MARS® Giant 360g FUNSIZE Bars FUNSIZE Bars Giant Bag Units per outer 12 Units per outer 12 REC RETAIL $4.79 REC RETAIL $5.99 SNICKERS® 216g SNICKERS® 360g FUNSIZE Bars FUNSIZE Bars Giant Bag Units per outer 12 Units per outer 12 REC RETAIL $4.79 REC RETAIL $5.99 -

Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020

k Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020 For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk CONTENTS 5 USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS 5 EXPLANATION OF KASHRUT SYMBOLS 5 PROBLEMATIC E NUMBERS 6 BISCUITS 6 BREAD 7 CHOCOLATE & SWEET SPREADS 7 CONFECTIONERY 18 CRACKERS, RICE & CORN CAKES 18 CRISPS & SNACKS 20 DESSERTS 21 ENERGY & PROTEIN SNACKS 22 ENERGY DRINKS 23 FRUIT SNACKS 24 HOT CHOCOLATE & MALTED DRINKS 24 ICE CREAM CONES & WAFERS 25 ICE CREAMS, LOLLIES & SORBET 29 MILK SHAKES & MIXES 30 NUTS & SEEDS 31 PEANUT BUTTER & MARMITE 31 POPCORN 31 SNACK BARS 34 SOFT DRINKS 42 SUGAR FREE CONFECTIONERY 43 SYRUPS & TOPPINGS 43 YOGHURT DRINKS 44 YOGHURTS & DAIRY DESSERTS The information in this guide is only applicable to products made for the UK market. All details are correct at the time of going to press but are subject to change. For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk. Sign up for email alerts and updates on www.kosher.org.uk or join Facebook KLBD Kosher Direct. No assumptions should be made about the kosher status of products not listed, even if others in the range are approved or certified. It is preferable, whenever possible, to buy products made under Rabbinical supervision. WARNING: The designation ‘Parev’ does not guarantee that a product is suitable for those with dairy or lactose intolerance. WARNING: The ‘Nut Free’ symbol is displayed next to a product based on information from manufacturers. The KLBD takes no responsibility for this designation. You are advised to check the allergen information on each product. k GUESS WHAT'S IN YOUR FOOD k USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS Hi Noshers! PRODUCTS WHICH ARE KLBD CERTIFIED Even in these difficult times, and perhaps now more than ever, Like many kashrut authorities around the world, the KLBD uses the American we need our Nosh! kosher logo system. -

Boxing Edition

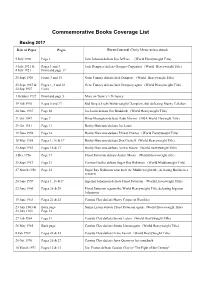

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25Th Dec, 2008

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25th DEc, 2008 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website My very best wishes to all my readers and thank you for the continued support you have given which I do appreciate a great deal. Name: Willie Pastrano Career Record: click Birth Name: Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano Nationality: US American Hometown: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Born: 1935-11-27 Died: 1997-12-06 Age at Death: 62 Stance: Orthodox Height: 6′ 0″ Trainers: Angelo Dundee & Whitey Esneault Manager: Whitey Esneault Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano was born in the Vieux Carrê district of New Orleans, Louisiana, on 27 November 1935. He had a hard upbringing, under the gaze of a strict father who threatened him with the belt if he caught him backing off from a confrontation. 'I used to run from fights,' he told American writer Peter Heller in 1970. 'And papa would see it from the steps. He'd take his belt, he'd say "All right, me or him?" and I'd go beat the kid: His father worked wherever and whenever he could, in shipyards and factories, sometimes as a welder, sometimes as a carpenter. 'I remember nine dollars a week paychecks,' the youngster recalled. 'Me, my mother, my step-brother, and my father and whatever hangers-on there were...there were always floaters in the family.' Pastrano was an overweight child but, like millions of youngsters at the time, he wanted to be a sports star like baseball's Babe Ruth. -

Sax Discrimination

%x Discrimination Number42 October 20, 1980 The last time I bent Current Con- whom [ spoke at the Congress could ten (s m readers’ collective ear to discuss understand why 1 wanted to do such an my love for the saxophone, I I said 1 had article. If 1 was at a scientific meeting never encountered a commercial record- and said [ was writing an article about ing by a woman saxophone player. A women scientists, there would be a high few readers wrote to me [o remedy this degree of interes[. [ would get a variety situation. A subsequent investigation of strong opinions on the subject of sex showed that there are relatively few discrimination in science. The lack of in- women sax players. However, we were terest on the part of the women sax- able to compile a brief list of recording~ ophone players indica[ed to me that made by women $axophonis[s. It ap- many in the world of music feel a musi- pears in Table 1. cian’s gender is irrelevant. Those women The paucity of’ women sax player~ 1spoke with at the WSC seemed to think raises the touchy question of sex dis- that if a woman had talent, she had no crimination. It is true that some of the problems in competing succe~sfully with greats of jazz are women. Ho}vever, ac- her male counterparts. But as we cording to some of the female saxi$ts we learned, not all women saxophonists feel spoke with, some forms of musical ex- this way. pression were considered “unladylike” One $tatement most women saxists for many years. -

Serving Professional Foodservice Kitchen Essentials & Impulse Snack Solutions Overview of Primeline’S Sales & Marketing Subsidiary of Primeline Group

SERVING PROFESSIONAL FOODSERVICE KITCHEN ESSENTIALS & IMPULSE SNACK SOLUTIONS OVERVIEW OF PRIMELINE’S SALES & MARKETING SUBSIDIARY OF PRIMELINE GROUP Logistics Express VNE Primeline Sales & Marketing is part of Primeline Group which is the largest independent Irish provider of logistics, sales and marketing services to home- SECTIONContents 1 – Primeline Sales & Marketing grown and international brands across the Irish and UK markets Based in Ashbourne Co. Meath and with over 30 years’ experience, we have developed SECTION 2 - Impulse Snacks long term relationships and work with some of the best retailers and foodservice operators on the island of Ireland. SECTION 3 - Beverages SECTION 4 - Ready Meal Solutions SECTION 5 – Kitchen Essentials: Foodservice Solutions for Kitchen Professionals SECTION 6 - Product Listings by Brand 1,000,000 Square feet of 25,000 4,500 200 hi-bay warehousing Deliveries Weekly Retailers Serviced Vehicles 1,000,000 30,000 1,000 Cases Delivered Product SKU’s Employees Weekly SECTION 1 | PRIMELINE SALES & MARKETING Welcome to the Primeline Foodservice Primeline Foodservice Guide Team & Awards At Primeline Foodservice exceptional customer Our Foodservice team have won service is at the heart of what we provide. We believe numerous industry awards for in delivering innovative and dynamic foodservice customer service and were very solutions that will grow our customers’ business. proud to have accepted “Overall Primeline represent some of the planet’s biggest and Supplier of The Year 2019” award home-grown consumer brands in Ireland and we from Compass Group Ireland. are delighted to be able to share our brand partner’s This was achieved by delivering foodservice selection with you today. -

AUGUST, 1940 TEN CENTS OFFICIAL STATE Vol

SMALL MOUTH BASS AUGUST, 1940 TEN CENTS OFFICIAL STATE Vol. 9—No. 8 PUBLICATION VNGLEIC AUGUST, 1940 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA PUBLISHED MONTHLY by the BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS PENNSYLVANIA BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS Publication Office: 540 Hamilton Street, Allentown. Penna. Executive and Editorial Offices: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Board of Fish Commis CHARLES A. FRENCH sioners, Harrisburg, Pa. Commissioner of Fisheries Ten cents a copy—50 cents a year MEMBERS OF BOARD • CHARLES A. FRENCH, Chairman Elwood City ALEX P. SWEIGART, Editor South Office Bldg., Harrisburg, Pa. MILTON L. PEEK Radnor HARRY E. WEBER NOTE Philipsburg Subscriptions to the PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER should be addressed to the Editor. Submit fee either by check or money order payable to the Common EDGAR W. NICHOLSON wealth of Pennsylvania. Stamps not acceptable. Philadelphia Individuals sending cash do so at their own risk. FRED McKEAN New Kensington PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER welcomes contribu tions and photos of catches from its readers. Proper H. R. STACKHOUSE credit will be given to contributors. Secretary to Board All contributions returned if accompanied by first class postage. Entered as second class matter at the Post Office C. R. BULLER of Allentown, Pa., under Act of March 3, 1879. Chief Fish Culturist, Bellefonte -tJKi IMPORTANT—The Editor should be notified immediately of change in subscriber's address Please give old and new addresses Permission to reprint will be granted provided proper credit notice is given S Vol. 9. No. 8 ANGLERA"VI^ W i»Cr 1%7. AUGUST 1940 EDITORIAL CONTROLLED BASS CULTURE NTENSE investigation and study of bass culture has been taking place in Pennsylvania in the past few years. -

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00

Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 Saturday 02 November 2013 11:00 International Autograph Auctions (IAA) Office address Foxhall Business Centre Foxhall Road NG7 6LH International Autograph Auctions (IAA) (Two Day Autograph Auction Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 tennis players of the 1970s TENNIS: An excellent collection including each Wimbledon Men's of 31 signed postcard Singles Champion of the decade. photographs by various tennis VG to EX All of the signatures players of the 1970s including were obtained in person by the Billie Jean King (Wimbledon vendor's brother who regularly Champion 1966, 1967, 1968, attended the Wimbledon 1972, 1973 & 1975), Ann Jones Championships during the 1970s. (Wimbledon Champion 1969), Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Evonne Goolagong (Wimbledon Champion 1971 & 1980), Chris Evert (Wimbledon Champion Lot: 2 1974, 1976 & 1981), Virginia TILDEN WILLIAM: (1893-1953) Wade (Wimbledon Champion American Tennis Player, 1977), John Newcombe Wimbledon Champion 1920, (Wimbledon Champion 1967, 1921 & 1930. A.L.S., Bill, one 1970 & 1971), Stan Smith page, slim 4to, Memphis, (Wimbledon Champion 1972), Tennessee, n.d. (11th June Jan Kodes (Wimbledon 1948?), to his protégé Arthur Champion 1973), Jimmy Connors Anderson ('Dearest Stinky'), on (Wimbledon Champion 1974 & the attractive printed stationery of 1982), Arthur Ashe (Wimbledon the Hotel Peabody. Tilden sends Champion 1975), Bjorn Borg his friend a cheque (no longer (Wimbledon Champion 1976, present) 'to cover your 1977, 1978, 1979 & 1980), reservation & ticket to Boston Francoise Durr (Wimbledon from Chicago' and provides Finalist 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, details of the hotel and where to 1973 & 1975), Olga Morozova meet in Boston, concluding (Wimbledon Finalist 1974), 'Crazy to see you'.