Cockroach Oyster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History and Decline of Ostrea Lurida in Willapa Bay, Washington Author(S): Brady Blake and Philine S

The History and Decline of Ostrea Lurida in Willapa Bay, Washington Author(s): Brady Blake and Philine S. E. Zu Ermgassen Source: Journal of Shellfish Research, 34(2):273-280. Published By: National Shellfisheries Association DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2983/035.034.0208 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2983/035.034.0208 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 34, No. 2, 273–280, 2015. THE HISTORY AND DECLINE OF OSTREA LURIDA IN WILLAPA BAY, WASHINGTON BRADY BLAKE1 AND PHILINE S. E. ZU ERMGASSEN2* 1Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife, 375 Hudson Street, Port Townsend, WA 98368; 2Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, United Kingdom ABSTRACT With an annual production of 1500 metric tons of shucked oysters, Willapa Bay, WA currently produces more oysters than any other estuary in the United States. -

Louisiana Oyster Landings, 2000-2014

Updated November 23, 2016 LouisianaFishery OysterManagement Plan Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Office of Fisheries Authors: Patrick Banks, Steve Beck, Katie Chapiesky, and Jack Isaacs Editor/Point of Contact: Katie Chapiesky, kchapiesky@ wlf.la.gov 1 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 INTRODUCTION 8 Definition of Management Unit 8 Management Authority and Process 8 Management Goals and Objectives 8 DESCRIPTION OF THE STOCK 9 Biological Profile 9 Physical Description 9 Distribution 9 Habitat 10 Reproduction 10 Age and Growth 10 Predator-Prey Relationships 10 Stock Status and Assessment Methods 11 Stock Unit Definition 11 Current Stock Assessment 11 Reference Points 12 Harvest Control Rules 12 Oyster Monitoring and Assessment Methods 13 Stock Resilience 15 DESCRIPTION OF THE FISHERY 17 Data Collection and Analyses 17 Commercial Fishery 18 Volume and Value of Landings 18 Landings by Season 20 Landings by Gear Type 20 Landings by Vessel Length 23 Landings by Area 24 Seed Harvest 25 Commercial Oystermen 27 2 Fishing Effort 27 Seafood Dealers 30 Fresh Products Licenseholders 31 Oyster Processors 31 Oyster Imports 33 Recreational Fishery 36 Economic Conditions 37 Interactions with Other Fisheries or User Groups 37 ECOSYSTEM CONSIDERATIONS AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS 38 Ecosystem Considerations 38 Habitat 38 Bycatch and Discards 40 Lost or Abandoned Fishing Gear 40 Environmental Factors 41 Hydrological Conditions 41 Invasive Species 41 Predation 41 Competition from Other Species 42 Diseases and Parasites -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Field Identification Guide to the Living Marine Resources In

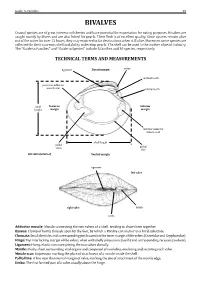

Guide to Families 29 BIVALVES Coastal species are of great interest to fisheries and have potential for exportation for eating purposes. Bivalves are caught mainly by divers and are also fished for pearls. Their flesh is of excellent quality. Since oysters remain alive out of the water for over 12 hours, they may exported to far destinations when still alive. Moreover, some species are collected for their nacreous shell and ability to develop pearls. The shell can be used in the mother of pearl industry. The “Guide to Families’’ andTECHNICAL ‘‘Guide to Species’’ TERMS include 5AND families MEASUREMENTS and 10 species, respectively. ligament Dorsal margin umbo posterior adductor cardinal tooth muscle scar lateral tooth Posterior Anterior margin margin shell height anterior adductor muscle scar pallial sinus pallial shell length line left valve (interior) Ventral margin ligament left valve right valve lunule umbo Adductor muscle: Byssus: Chomata: Muscle connecting the two valves of a shell, tending to draw them together. Hinge: Clump of horny threads spun by the foot, by which a Bivalve can anchor to a hard substrate. Ligament: Small denticles and corresponding pits located on the inner margin of the valves (Ostreidae and Gryphaeidae). Mantle: Top interlocking margin of the valves, often with shelly projections (teeth) and corresponding recesses (sockets). Muscle scar: Horny, elastic structure joining the two valves dorsally. Pallial line: Fleshy sheet surrounding vital organs and composed of two lobes, one lining and secreting each valve. Umbo: Impression marking the place of attachment of a muscle inside the shell. A line near the internal margin of valve, marking the site of attachment of the mantle edge. -

Shellfish Reefs at Risk

SHELLFISH REEFS AT RISK A Global Analysis of Problems and Solutions Michael W. Beck, Robert D. Brumbaugh, Laura Airoldi, Alvar Carranza, Loren D. Coen, Christine Crawford, Omar Defeo, Graham J. Edgar, Boze Hancock, Matthew Kay, Hunter Lenihan, Mark W. Luckenbach, Caitlyn L. Toropova, Guofan Zhang CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Methods .................................................................................................................................... 10 Results ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Condition of Oyster Reefs Globally Across Bays and Ecoregions ............ 14 Regional Summaries of the Condition of Shellfish Reefs ............................ 15 Overview of Threats and Causes of Decline ................................................................ 28 Recommendations for Conservation, Restoration and Management ................ 30 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................ 36 References ............................................................................................................................. -

Santa Fe New Mexican, 04-27-1901 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 4-27-1901 Santa Fe New Mexican, 04-27-1901 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe New Mexican, 04-27-1901." (1901). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/1024 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SANTA FE NEW MEXICAN NO. 58 VOL. 38 SANTA FE, N. M., SATURDAY, APRIL 27, 1901. AN IMPORTANT ARREST. BRYAN'S FDTORE. ON FRIENDLY NOT THE OUR RELATIONS Rambler William Wilson Accused of the It is Discussed at Length By the Editor of FOOTING AGAIN Furnishing SHERIFF'S FAOLT CUBA Used WITH the Omaha Bee. Revolver and Ammunition New York, April 27. Edward Rose-wate- r, at the Penitentiary. editor of the Omaha. Bee, Is quo- For-- William alias MeGinty, has Sheriff Salome Garcia of Called Austria and Mexico Decide to , Wilson, Clayton, The Cuban Commission Upon ted iby the Times as saying last night: been arrested at Albuquerque upon a n, Answers An an pin-to- Each Other About the McFle Union County, President McKinley Today to "William Jennings Bryan, my give bench warrant Issued by Judge will Itae the candidate for governor ' Maximilian Affair, on the charge of having furnished the Important Question, Bid Him Farewell. -

Early Ontogeny of Jurassic Bakevelliids and Their Bearing on Bivalve Evolution

Early ontogeny of Jurassic bakevelliids and their bearing on bivalve evolution NIKOLAUS MALCHUS Malchus, N. 2004. Early ontogeny of Jurassic bakevelliids and their bearing on bivalve evolution. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 49 (1): 85–110. Larval and earliest postlarval shells of Jurassic Bakevelliidae are described for the first time and some complementary data are given concerning larval shells of oysters and pinnids. Two new larval shell characters, a posterodorsal outlet and shell septum are described. The outlet is homologous to the posterodorsal notch of oysters and posterodorsal ridge of arcoids. It probably reflects the presence of the soft anatomical character post−anal tuft, which, among Pteriomorphia, was only known from oysters. A shell septum was so far only known from Cassianellidae, Lithiotidae, and the bakevelliid Kobayashites. A review of early ontogenetic shell characters strongly suggests a basal dichotomy within the Pterio− morphia separating taxa with opisthogyrate larval shells, such as most (or all?) Praecardioida, Pinnoida, Pterioida (Bakevelliidae, Cassianellidae, all living Pterioidea), and Ostreoida from all other groups. The Pinnidae appear to be closely related to the Pterioida, and the Bakevelliidae belong to the stem line of the Cassianellidae, Lithiotidae, Pterioidea, and Ostreoidea. The latter two superfamilies comprise a well constrained clade. These interpretations are con− sistent with recent phylogenetic hypotheses based on palaeontological and genetic (18S and 28S mtDNA) data. A more detailed phylogeny is hampered by the fact that many larval shell characters are rather ancient plesiomorphies. Key words: Bivalvia, Pteriomorphia, Bakevelliidae, larval shell, ontogeny, phylogeny. Nikolaus Malchus [[email protected]], Departamento de Geologia/Unitat Paleontologia, Universitat Autòno− ma Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès), Spain. -

Olympia Oyster (Ostrea Lurida)

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea lurida in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2011 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2011. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea lurida in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 56 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 30 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Gillespie, G.E. 2000. COSEWIC status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-30 pp. Production note: COSEWIC acknowledges Graham E. Gillespie for writing the provisional status report on the Olympia Oyster, Ostrea lurida, prepared under contract with Environment Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The contractor’s involvement with the writing of the status report ended with the acceptance of the provisional report. Any modifications to the status report during the subsequent preparation of the 6-month interim and 2-month interim status reports were overseen by Robert Forsyth and Dr. Gerald Mackie, COSEWIC Molluscs Specialist Subcommittee Co-Chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’huître plate du Pacifique (Ostrea lurida) au Canada. -

Maryland's Lower Choptank River Cultural Resource Inventory

Maryland’s Lower Choptank River Cultural Resource Inventory by Ralph E. Eshelman and Carl W. Scheffel, Jr. “So long as the tides shall ebb and flow in Choptank River.” From Philemon Downes will, Hillsboro, circa 1796 U.S. Geological Survey Quadrangle 7.5 Minute Topographic maps covering the Lower Choptank River (below Caroline County) include: Cambridge (1988), Church Creek (1982), East New Market (1988), Oxford (1988), Preston (1988), Sharp Island (1974R), Tilghman (1988), and Trappe (1988). Introduction The Choptank River is Maryland’s longest river of the Eastern Shore. The Choptank River was ranked as one of four Category One rivers (rivers and related corridors which possess a composite resource value with greater than State signific ance) by the Maryland Rivers Study Wild and Scenic Rivers Program in 1985. It has been stated that “no river in the Chesapeake region has done more to shape the character and society of the Eastern Shore than the Choptank.” It has been called “the noblest watercourse on the Eastern Shore.” Name origin: “Chaptanck” is probably a composition of Algonquian words meaning “it flows back strongly,” referring to the river’s tidal changes1 Geological Change and Flooded Valleys The Choptank River is the largest tributary of the Chesapeake Bay on the eastern shore and is therefore part of the largest estuary in North America. This Bay and all its tributaries were once non-tidal fresh water rivers and streams during the last ice age (15,000 years ago) when sea level was over 300 feet below present. As climate warmed and glaciers melted northward sea level rose, and the Choptank valley and Susquehanna valley became flooded. -

A History of Oysters in Maine (1600S-1970S) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected]

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Darling Marine Center Historical Documents Darling Marine Center Historical Collections 3-2019 A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) Randy Lackovic University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Lackovic, Randy, "A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s)" (2019). Darling Marine Center Historical Documents. 22. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/dmc_documents/22 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Darling Marine Center Historical Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A History of Oysters in Maine (1600s-1970s) This is a history of oyster abundance in Maine, and the subsequent decline of oyster abundance. It is a history of oystering, oyster fisheries, and oyster commerce in Maine. It is a history of the transplanting of oysters to Maine, and experiments with oysters in Maine, and of oyster culture in Maine. This history takes place from the 1600s to the 1970s. 17th Century {}{}{}{} In early days, oysters were to be found in lavish abundance along all the Atlantic coast, though Ingersoll says it was at least a small number of oysters on the Gulf of Maine coast.86, 87 Champlain wrote that in 1604, "All the harbors, bays, and coasts from Chouacoet (Saco) are filled with every variety of fish. -

Materials for a Rejang-Indonesian-English Dictionary

PACIFIC LING U1STICS Series D - No. 58 MATERIALS FOR A REJANG - INDONESIAN - ENGLISH DICTIONARY collected by M.A. Jaspan With a fragmentary sketch of the . Rejang language by W. Aichele, and a preface and additional annotations by P. Voorhoeve (MATERIALS IN LANGUAGES OF INDONESIA, No. 27) W.A.L. Stokhof, Series Editor Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Jaspan, M.A. editor. Materials for a Rejang-Indonesian-English dictionary. D-58, x + 172 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1984. DOI:10.15144/PL-D58.cover ©1984 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A - Occasional Papers SERIES B - Monographs SERIES C - Books SERIES D - Special Publications EDITOR: S.A. Wurm ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W. Bender K.A. McElhanon University of Hawaii University of Texas David Bradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii A. Capell P. MUhlhiiusler University of Sydney Linacre College, Oxford Michael G. Clyne G.N. O'Grady Monash University University of Victoria, B.C. S.H. Elbert A.K. Pawley University of Hawaii University of Auckland K.J. Franklin K.L. Pike University of Michigan; Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W. Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W. Grace Malcolm Ross University of Hawaii University of Papua New Guinea M.A.K. -

Living in Korea

A Guide for International Scientists at the Institute for Basic Science Living in Korea A Guide for International Scientists at the Institute for Basic Science Contents ⅠOverview Chapter 1: IBS 1. The Institute for Basic Science 12 2. Centers and Affiliated Organizations 13 2.1 HQ Centers 13 2.1.1 Pioneer Research Centers 13 2.2 Campus Centers 13 2.3 Extramural Centers 13 2.4 Rare Isotope Science Project 13 2.5 National Institute for Mathematical Sciences 13 2.6 Location of IBS Centers 14 3. Career Path 15 4. Recruitment Procedure 16 Chapter 2: Visas and Immigration 1. Overview of Immigration 18 2. Visa Types 18 3. Applying for a Visa Outside of Korea 22 4. Alien Registration Card 23 5. Immigration Offices 27 5.1 Immigration Locations 27 Chapter 3: Korean Language 1. Historical Perspective 28 2. Hangul 28 2.1 Plain Consonants 29 2.2 Tense Consonants 30 2.3 Aspirated Consonants 30 2.4 Simple Vowels 30 2.5 Plus Y Vowels 30 2.6 Vowel Combinations 31 3. Romanizations 31 3.1 Vowels 32 3.2 Consonants 32 3.2.1 Special Phonetic Changes 33 3.3 Name Standards 34 4. Hanja 34 5. Konglish 35 6. Korean Language Classes 38 6.1 University Programs 38 6.2 Korean Immigration and Integration Program 39 6.3 Self-study 39 7. Certification 40 ⅡLiving in Korea Chapter 1: Housing 1. Measurement Standards 44 2. Types of Accommodations 45 2.1 Apartments/Flats 45 2.2 Officetels 46 2.3 Villas 46 2.4 Studio Apartments 46 2.5 Dormitories 47 2.6 Rooftop Room 47 3.