Sport As a Context for Integration: Newly Arrived Immigrant Children in Sweden Drawing Sporting Experiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPORT and VIOLENCE a Critical Examination of Sport

SPORT AND VIOLENCE A Critical Examination of Sport 2nd Edition Thomas J. Orr • Lynn M. Jamieson SPORT AND VIOLENCE A Critical Examination of Sport 2nd Edition Thomas J. Orr Lynn M. Jamieson © 2020 Sagamore-Venture All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. Publishers: Joseph J. Bannon/Peter Bannon Sales and Marketing Manager: Misti Gilles Director of Development and Production: Susan M. Davis Graphic Designer: Marissa Willison Production Coordinator: Amy S. Dagit Technology Manager: Mark Atkinson ISBN print edition: 978-1-57167-979-6 ISBN etext: 978-1-57167-980-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020939042 Printed in the United States. 1807 N. Federal Dr. Urbana, IL 61801 www.sagamorepublishing.com Dedication “To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme. No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, though many there be that have tried it.” Herman Melville, my ancestor and author of the classic novel Moby Dick, has passed this advice forward to myself and the world in this quote. The dynamics of the sports environment have proven to be a very worthy topic and have provided a rich amount of material that investigates the actions, thoughts, and behaviors of people as they navigate their way through a social environment that we have come to know as sport. By avoiding the study of fleas, I have instead had to navigate the deep blue waters of research into finding the causes, roots, and solutions to a social problem that has become figuratively as large as the mythical Moby Dick that my great-great uncle was in search of. -

International Guidelines for Sports in Sweden

International guidelines for sports in Sweden International guidelines The Swedish Sports Confederation (RF) has been mandated to work with matters of common concern for the sports movement, both nationally and internationally (in accordance with Chapter 2 of RF’s Statutes). The task of the Swedish Sports Confederation in its international work is to represent the Swedish sports movement at an international level to create favourable conditions for sport in Sweden, and also to stimulate and in various ways support special sports federations (SF) in their international activities. This also means assisting through making its competence available with the aim of developing the sport internationally. The Swedish sports movement will exercise powerful international influence through coordination. These Guidelines are based on a belief in the sports movement as an international meeting place and bridge-builder between people. This is founded on the independence and impartiality of the sports movement. The sports movement has no party political or religious affiliations and can, in many cases, aid increased openness throughout the world. We have also observed at the same time that political leaders may sometimes exploit major sports competitions with ulterior motives. The position of the sports movement is that it should be possible for athletes to have whatever nationality, religion or political views they wish yet still participate on equal terms. It is then that sport’s potential as a meeting place is greatest. These International Guidelines set out fundamental standpoints for the international action of the Swedish sports movement. This requires each SF to apply the Guidelines in their international exchanges and participation. -

Sport As a Context for Integration: Newly Arrived Immigrant Children in Sweden Drawing Sporting Experiences

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 18; October 2013 Sport as a Context for Integration: Newly Arrived Immigrant Children in Sweden Drawing Sporting Experiences Associate Professor Krister Hertting, PhD Luleå University of Technology Department of Arts, Communication and Education SE-971 87 Luleå Inger Karlefors, PhD Luleå University of Technology Department of Arts, Communication and Education SE-971 87 Luleå Abstract Sport is a global phenomenon, which can make sport an important arena for integration into new societies. However, sport is also an expression of national culture and identities. The aim of this study is to explore images and experiences that newly-arrived immigrant children in Sweden have about sport in their country of origin, and challenges that can arise in processes of integration through sport. We asked 20 newly arrived children aged 10 to 13 to make drawings about sporting experiences from their countries of origin. Three themes emerged: sport as feeling joy, where activities were performed with friends during leisure time; sport as acting formally, where activities were carried out in clubs; and sport as a spectator, where children were non-participants. We emphasise that development of sport should be two-way processes, where cultural learning should be mutual processes. Immigrant children’s experiences should be foregrounded when utilising and developing sports programmes. Keywords: sports for all, immigrant children, qualitative methods, phenomenology 1. Introduction Like many other countries, Sweden has become a multicultural society during the last few decades. Two million out of a population of nine million have immigrant backgrounds that represent more than 200 different cultures. -

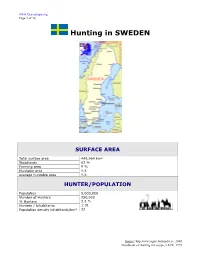

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

CSR in Swedish Football

CSR in Swedish football A multiple case study of four clubs in Allsvenskan By: Lina Nilsson 2018-10-09 Supervisors: Marcus Box, Lars Vigerland and Erik Borg Södertörn University | School of Social Sciences Master Thesis 30 Credits Business Administration | Spring term 2018 ABSTRACT The question of companies’ social responsibility taking, called Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), has been widely debated in research since the 1900s. However, the research connecting CSR to sport was not started until the beginning of the 2000s, meaning that there are still many gaps in sport research that has to be filled. One such gap is research on CSR in a Swedish football context. Accordingly, the purpose of the study was firstly to examine how and why Swedish football clubs – organised as non-profit associations or sports corporations – work with CSR, and secondly whether or not there was a difference in the CSR work of the two organisational forms. A multiple case study of four clubs in Allsvenskan was carried out, examining the CSR work – meaning the CSR concept and activities, the motives for engaging in CSR and the role of the stakeholders – in detail. In addition, the CSR actions of all clubs of Allsvenskan were briefly investigated. The findings of the study showed that the four clubs of the multiple case study had focused their CSR concepts in different directions and performed different activities. As a consequence, they had developed different competences and competitive advantages. Furthermore, the findings suggested that the motives for engaging in CSR were a social agenda, pressure from stakeholders and financial motives. -

The Birth of Swedish Ice Hockey : Antwerp 1920

The Birth of Swedish Ice Hockey : Antwerp 1920 Hansen, Kenth Published in: Citius, altius, fortius : the ISOH journal 1996 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hansen, K. (1996). The Birth of Swedish Ice Hockey : Antwerp 1920. Citius, altius, fortius : the ISOH journal, 4(2), 5-27. http://library.la84.org/SportsLibrary/JOH/JOHv4n2/JOHv4n2c.pdf Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 THE BIRTH OF SWEDISH ICE HOCKEY - ANTWERP 1920 by Kenth Hansen Introduction The purpose of this paper is to describe how the Swedes began playing ice hockey and to document the first Olympic ice hockey tournament in Antwerp in 1920, since both events happened at the same time. -

Kingdom of Sweden

Johan Maltesson A Visitor´s Factbook on the KINGDOM OF SWEDEN © Johan Maltesson Johan Maltesson A Visitor’s Factbook to the Kingdom of Sweden Helsingborg, Sweden 2017 Preface This little publication is a condensed facts guide to Sweden, foremost intended for visitors to Sweden, as well as for persons who are merely interested in learning more about this fascinating, multifacetted and sadly all too unknown country. This book’s main focus is thus on things that might interest a visitor. Included are: Basic facts about Sweden Society and politics Culture, sports and religion Languages Science and education Media Transportation Nature and geography, including an extensive taxonomic list of Swedish terrestrial vertebrate animals An overview of Sweden’s history Lists of Swedish monarchs, prime ministers and persons of interest The most common Swedish given names and surnames A small dictionary of common words and phrases, including a small pronounciation guide Brief individual overviews of all of the 21 administrative counties of Sweden … and more... Wishing You a pleasant journey! Some notes... National and county population numbers are as of December 31 2016. Political parties and government are as of April 2017. New elections are to be held in September 2018. City population number are as of December 31 2015, and denotes contiguous urban areas – without regard to administra- tive division. Sports teams listed are those participating in the highest league of their respective sport – for soccer as of the 2017 season and for ice hockey and handball as of the 2016-2017 season. The ”most common names” listed are as of December 31 2016. -

SWEDEN of Feeling, Awareness of Strength of Doom, Absence of Sentimentality, Principle, Avoidance of the Visitor

© Lonely Planet Publications 1116 Sweden HIGHLIGHTS Stockholm Touring the waterways, exploring top-notch museums and wandering the cobblestoned backstreets of Gamla Stan ( p1123 ) Göteborg Explore cutting-edge style and the secrets of the underground in Sweden’s ‘second city’ ( p1140 ) Ice Hotel Enjoying a frosty beverage and a frozen bed at this ultracool jewel in the far north ( p1145 ) Malmö Getting as close to the continent as possible without leaving the country in this multicultural city ( p1136 ) Off-the-beaten track Doing a bicycle loop around the island of Gotland, the best budget SWEDEN SWEDEN destination in Sweden ( p1135 ) FAST FACTS Area 449,964 sq km Budget Skr700 to Skr1000 per day Capital Stockholm Country code %46 Famous for Vikings, Volvos, blondes, ABBA, meatballs, Ikea Languages Swedish plus five official minority languages Money Swedish krona (Skr); A$1 = Skr5.95; C$1 = Skr6.75; €1 = Skr10.70; ¥100 = Skr8.40; NZ$1 = Skr4.66; Population 9.02 million UK£1 = Skr12.06; US$1 = Skr7.96 Visas not needed for most visitors for stays Phrases hej (hello), hej då (goodbye), ja of up to three months (yes), nej (no), tack (thanks) TRAVEL HINTS Eat out at lunchtime, buy your alcohol duty-free, and take advantage of Sweden’s excellent hostels and friendliness towards free camping. ROAMING SWEDEN Soak up Stockholm style, dig into Uppsala, Göteborg and Malmö, and explore some islands – big (Gotland) or small (Stockholm archipelago). At first glance, Sweden might not seem like a terribly outlandish place. But the more time you spend here, the stranger and more wonderfully foreign it becomes. -

Sport and Discrimination in Europe

SPORTS POLICY AND PRACTICE SERIES This work presents the main contributions and considerations of young European research Sport anddiscriminationinEurope workers and journalists on the question of discrimination in sport. Taking a multidisciplinary approach to the social sciences, the authors show how the media and those working in media can act as a relay, through their coverage of sports, for initiatives on the fi ght against discrimination. They also illustrate in detail not only the reality of discrimination in sport and the controversy surrounding this issue in the member states of the Council of Europe, but also the strength of research incipient in this fi eld. The Enlarged Partial Agreement on Sport (EPAS) hopes to contribute in this way to the development of European research on education through sport involving researchers from different countries in order to better understand the phenomenon of discrimination. William Gasparini is a professor at the University of Strasbourg where he directs a research laboratory specialising in social sciences in sport. He is the author of numerous works on sport in France and in Europe and is a member of the scientifi c and technical committee of the Agency for Education through Sport (APELS). Clotilde Talleu obtained her PhD in social sciences of sport from the University of Strasbourg. Foreword: interview with Lilian Thuram. The Enlarged Partial Agreement on Sport (EPAS) is an agreement between a number of Council of Europe member states (33 as of 1 March 2010) which have decided to co-operate in the fi eld of sports policy. As an “enlarged” agreement, the EPAS is open to non-member states. -

Government Support, Youth Sport and the Social Gradient in Sweden

Sport on (un)Even Terms? Government Support, Youth Sport and the Social Gradient in Sweden Norberg, Johan1 and Åkesson, Joakim2 1: Malmö university, Sweden; 2: Linnæus University, Sweden [email protected] Aim The aim of this paper is to analyse to what extent government subsidies for youth sports activities in Sweden is designed to counter socio-economic challenges. First, we study the occurrence of a social gradient in Swedish youth sport – i.e. a link between social position and sport participation among adolescents – by a multivariate regression analysis in which youth sport activity levels in local clubs are examined in relation to socio-demographic data in the municipalities in which the clubs operate. Secondly, we analyse the findings in relation to the structure and impact of the Swedish governments subsidies for youth sports activities. We argue that subsidies based on levels of activities promote than counteract socioeconomic differences in youth sports. Theoretical Background and Literature Review In Sweden, state support to sport is – above all – welfare policy. The overarching aim of the government’s support to organized sports is to promote public health, physical activity and recreation, especially among adolescents (Berggard & Norberg, 2010; Norberg 2018). However, despite an ambition to provide “sports for all” and to facilitate for underprivileged groups to participate in sports, actual research about social stratification in Swedish children's and youth sports is limited. Blomdahl et al have studied youth leisure habits and living conditions in a selection of Swedish municipalities and shown that children and young people with high social position participate in club sports more than youngsters in low socio- economic groups (Blomdahl, Elofsson, Åkesson & Lengheden, 2014). -

ED084249.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 084 249 SP 007 485 TITLE Sport for All. Five Countries Report. INSTITUTION Council for Cultural Cooperation, Strasbourg (France) . PUB DATE 70 NOTE 135p. AVAILABLE FROM Manhattan Publishing Company, 225 Lafayette Street, New York 12, NY($3.00) EDRS PRICE EF-$0.65 HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Athletic Activities; *Athletics; *Foreign Countries; *National Programs; Physical Activities; Physiology; *Sociocultural Patterns; Teacher Education; Womens Athletics IDENTIFIERS Sport for All ABSTRACT This document is a compendium of reports from five countries on their "Sport for All" programs. The five countries are the Federal Republic of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdor.. It.is stated that the basic idea of "Sport for All" is of a sociocultural nature: it regards sport and its functions as an integral part of permanent education. All of the reports place emphasis on medico-biological motives, sociological. motives (the question of the use of leisure time), and educational motives (the place of sport in our civilization as a whole). Topics covered in the five reports are various methodologies of each country's program, the attitude of women towards sport, the training of instructors, the general public response, and the future needs of the "Sport for All" program. (Related document is SP 007.501.) (JA) IJ(;,.)`)IIIINI1U {el I t)yr. It ,,,A1BY MICRO FIcHE ONLY N WI' COL4 1)1 C.1 OF Ili l-K0ANI, out ,,,N1 /:, ON', OPt PT. ,.{Ot 1$i ilf)t.):10,1,11 ()It t)I;( t t Pt, Otlk!(nON Do I 'ODI 1111 t P. -

CSR, Glocalisation and Football

Malmö University Faculty of Education and Society Department of Sport Science Bachelor Degree Thesis 15 credits CSR, Glocalisation and Football A comparison between American and Swedish football CSR, Glokalisering och Fotboll En jämförelse mellan amerikansk och svensk fotboll ST 2015 Tim N. Rosell 910117 Sport science program 180hp Examiner: Torbjörn Andersson Sport Management Supervisors: Bo Carlsson and 2015-06-23 Gun Normark 2 Preface Growing up in segregated areas I discovered that sport is more than physical activity, it is a second language, enabling multicultural societies to converge. It is with this back- ground the CSR concept in sport appeals, how sport can give and ultimately be given something in return. Hopefully, this thesis will serve as organisational moderator for how CSR could be implemented and used in professional football clubs and leagues. Conclusively, I would like to thank my supervisors, Bo Carlsson and Gun Normark for providing me with guidance and expertise throughout the process. I would also like to thank my respondents, Mr. David Tenney and Filip Lundberg, for enabling an insight in the world of professional football organisations. Pleasant reading! _________________ Tim N. Rosell Malmö 2015-06-23 3 Abstract Keywords: Globalisation, Americanisation, Europeanisation, Glocalisa- tion and CSR Author: Tim Nathanael Rosell Supervisors: Bo Carlsson and Gun Normark Title: CSR, Glocalisation and Football - A comparison between American and Swedish football Problem: In the restricted Swedish Sports model, clubs in Sweden aims attract sponsors, create revenue and gain an advantage over their competitors. The problem is finding an economic governance method compatible with the internal legislative system. Purpose: The purpose is to illuminate globalisation processes in foot- ball and investigate the concept of CSR in the context of Se- attle Sounders and Djurgården IF.