The Birth of Swedish Ice Hockey : Antwerp 1920

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sports-Related Eye Injuries: Floorball Endangers the Eyes of Young Players

Scand J Med Sci Sports 2007: 17: 556–563 Copyright & 2006 The Authors Printed in Singapore . All rights reserved Journal compilation & 2006 Blackwell Munksgaard DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00607.x Sports-related eye injuries: floorball endangers the eyes of young players T. Leivo, I. Puusaari, T. Ma¨kitie Helsinki University Central Hospital, Ophthalmology Clinic, HUS, Finland Corresponding author: T. Leivo, MD, PhD, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Ophthalmology Clinic, PL 220, 00029 HUS, Finland. Tel: 1358 9 4711, E-mail: tiina.leivo@pp.fimnet.fi Accepted for publication 19 September 2006 The objectives of this study were to determine the distribu- CI 228–415) floorball eye injuries occur annually. The tion of different sports-related eye injuries and to identify mean age of floorball patients was 22 years. The most injury types to enable recommendations to be made about common finding (55%) in sports injury patients was hy- the use of protective eyewear. The study population phema. Clinically severe eye injuries during this period comprises all 565 eye trauma patients examined at the accounted for one-fourth of all cases. During the study Ophthalmology Emergency Clinic of the Helsinki Univer- period, no eye injury was found in an organized junior ice sity Central Hospital over a 6-month period. Data were hockey, where facial protection is mandatory. Floorball is collected from patient histories and questionnaires. In estimated to belong to the highest risk group in sports, and addition, three severe floorball eye injury cases are pre- thus, the use of protective eyewear is strongly recommended. sented. Of the 565 eye traumas, 94 (17%) were sports We conclude that national floorball federations should make related. -

Floorball As a New Sport

Rositsa Bliznakova Floorball as a New Sport Case Study: Bulgaria as a Floorball Destination from Insider’s Point of View University of Jyväskylä Department of Sport Sciences Social Sciences of Sport Master’s Thesis Spring 2011 2 UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ Department of Sport Sciences/Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences Master’s Degree Programme in Sport Science and Management BLIZNAKOVA, ROSITSA Floorball as a New Sport Case Study: Bulgaria as a Floorball Destination from Insider’s Point of View Master’s Thesis, 95 pages (Appendices 3 pages) Social Sciences of Sport Spring 2011 ABSTRACT Floorball is a relatively new but quickly growing sport. Together with its development and spreading its importance grows as well. However previously conducted research on floorball from its managerial point of view is rare, especially on an international scale. The present investigation makes an attempt to fill this gap in a holistic manner. It explores the research problem of finding the potentials of floorball as a sustainably successful sport – worldwide and in the case country, Bulgaria. For this purpose the study utilizes the tasks of collecting and systematizing existing relevant data, binding floorball to theoretical frameworks of contemporary science and observing its development level and current issues globally and locally. The research uses a qualitative, ethnographic approach to obtain its goals, and includes participant observation, unstructured and semi-structured interviews. Data is analysed through a combination of qualitative analysis tools – thematic analysis, discourse analysis, content analysis, visual data analysis, etc. The primary data has been gathered in Finland, as well as in Bulgaria and consists of observation of key events and interaction with key informants. -

SPORT and VIOLENCE a Critical Examination of Sport

SPORT AND VIOLENCE A Critical Examination of Sport 2nd Edition Thomas J. Orr • Lynn M. Jamieson SPORT AND VIOLENCE A Critical Examination of Sport 2nd Edition Thomas J. Orr Lynn M. Jamieson © 2020 Sagamore-Venture All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. Publishers: Joseph J. Bannon/Peter Bannon Sales and Marketing Manager: Misti Gilles Director of Development and Production: Susan M. Davis Graphic Designer: Marissa Willison Production Coordinator: Amy S. Dagit Technology Manager: Mark Atkinson ISBN print edition: 978-1-57167-979-6 ISBN etext: 978-1-57167-980-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020939042 Printed in the United States. 1807 N. Federal Dr. Urbana, IL 61801 www.sagamorepublishing.com Dedication “To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme. No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, though many there be that have tried it.” Herman Melville, my ancestor and author of the classic novel Moby Dick, has passed this advice forward to myself and the world in this quote. The dynamics of the sports environment have proven to be a very worthy topic and have provided a rich amount of material that investigates the actions, thoughts, and behaviors of people as they navigate their way through a social environment that we have come to know as sport. By avoiding the study of fleas, I have instead had to navigate the deep blue waters of research into finding the causes, roots, and solutions to a social problem that has become figuratively as large as the mythical Moby Dick that my great-great uncle was in search of. -

International Guidelines for Sports in Sweden

International guidelines for sports in Sweden International guidelines The Swedish Sports Confederation (RF) has been mandated to work with matters of common concern for the sports movement, both nationally and internationally (in accordance with Chapter 2 of RF’s Statutes). The task of the Swedish Sports Confederation in its international work is to represent the Swedish sports movement at an international level to create favourable conditions for sport in Sweden, and also to stimulate and in various ways support special sports federations (SF) in their international activities. This also means assisting through making its competence available with the aim of developing the sport internationally. The Swedish sports movement will exercise powerful international influence through coordination. These Guidelines are based on a belief in the sports movement as an international meeting place and bridge-builder between people. This is founded on the independence and impartiality of the sports movement. The sports movement has no party political or religious affiliations and can, in many cases, aid increased openness throughout the world. We have also observed at the same time that political leaders may sometimes exploit major sports competitions with ulterior motives. The position of the sports movement is that it should be possible for athletes to have whatever nationality, religion or political views they wish yet still participate on equal terms. It is then that sport’s potential as a meeting place is greatest. These International Guidelines set out fundamental standpoints for the international action of the Swedish sports movement. This requires each SF to apply the Guidelines in their international exchanges and participation. -

Iihf Official Inline Rule Book

IIHF OFFICIAL INLINE RULE BOOK 2015–2018 No part of this publication may be reproduced in the English language or translated and reproduced in any other language or transmitted in any form or by any means electronically or mechanically including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing from the International Ice Hockey Federation. July 2015 © International Ice Hockey Federation IIHF OFFICIAL INLINE RULE BOOK 2015–2018 RULE BOOK 11 RULE 1001 THE INTERNATIONAL ICE HOCKEY FEDERATION (IIHF) AS GOVERNING BODY OF INLINE HOCKEY 12 SECTION 1 – TERMINOLOGY 13 SECTION 2 – COMPETITION STANDARDS 15 RULE 1002 PLAYER ELIGIBILITY / AGE 15 RULE 1003 REFEREES 15 RULE 1004 PROPER AUTHORITIES AND DISCIPLINE 15 SECTION 3 – THE FLOOR / PLAYING AREA 16 RULE 1005 FLOOR / FIT TO PLAY 16 RULE 1006 PLAYERS’ BENCHES 16 RULE 1007 PENALTY BOXES 18 RULE 1008 OBJECTS ON THE FLOOR 18 RULE 1009 STANDARD DIMENSIONS OF FLOOR 18 RULE 1010 BOARDS ENCLOSING PLAYING AREA 18 RULE 1011 PROTECTIVE GLASS 19 RULE 1012 DOORS 20 RULE 1013 FLOOR MARKINGS / ZONES 20 RULE 1014 FLOOR MARKINGS/FACEOFF CIRCLES AND SPOTS 21 RULE 1015 FLOOR MARKINGS/HASH MARKS 22 RULE 1016 FLOOR MARKINGS / CREASES 22 RULE 1017 GOAL NET 23 SECTION 4 – TEAMS AND PLAYERS 24 RULE 1018 TEAM COMPOSITION 24 RULE 1019 FORFEIT GAMES 24 RULE 1020 INELIGIBLE PLAYER IN A GAME 24 RULE 1021 PLAYERS DRESSED 25 RULE 1022 TEAM PERSONNEL 25 RULE 1023 TEAM OFFICIALS AND TECHNOLOGY 26 RULE 1024 PLAYERS ON THE FLOOR DURING GAME ACTION 26 RULE 1025 CAPTAIN -

Sport As a Context for Integration: Newly Arrived Immigrant Children in Sweden Drawing Sporting Experiences

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 18; October 2013 Sport as a Context for Integration: Newly Arrived Immigrant Children in Sweden Drawing Sporting Experiences Associate Professor Krister Hertting, PhD Luleå University of Technology Department of Arts, Communication and Education SE-971 87 Luleå Inger Karlefors, PhD Luleå University of Technology Department of Arts, Communication and Education SE-971 87 Luleå Abstract Sport is a global phenomenon, which can make sport an important arena for integration into new societies. However, sport is also an expression of national culture and identities. The aim of this study is to explore images and experiences that newly-arrived immigrant children in Sweden have about sport in their country of origin, and challenges that can arise in processes of integration through sport. We asked 20 newly arrived children aged 10 to 13 to make drawings about sporting experiences from their countries of origin. Three themes emerged: sport as feeling joy, where activities were performed with friends during leisure time; sport as acting formally, where activities were carried out in clubs; and sport as a spectator, where children were non-participants. We emphasise that development of sport should be two-way processes, where cultural learning should be mutual processes. Immigrant children’s experiences should be foregrounded when utilising and developing sports programmes. Keywords: sports for all, immigrant children, qualitative methods, phenomenology 1. Introduction Like many other countries, Sweden has become a multicultural society during the last few decades. Two million out of a population of nine million have immigrant backgrounds that represent more than 200 different cultures. -

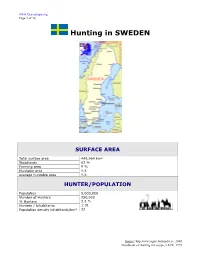

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

OHSAA Handbook for Match Type)

2021-22 Handbook for Member Schools Grades 7 to 12 CONTENTS About the OHSAA ...............................................................................................................................................................................4 Who to Contact at the OHSAA ...........................................................................................................................................................5 OHSAA Board of Directors .................................................................................................................................................................6 OHSAA Staff .......................................................................................................................................................................................7 OHSAA Board of Directors, Staff and District Athletic Boards Listing .............................................................................................8 OHSAA Association Districts ...........................................................................................................................................................10 OHSAA Affiliated Associations ........................................................................................................................................................11 Coaches Associations’ Proposals Timelines ......................................................................................................................................11 2021-22 OHSAA Ready Reference -

SITTING VOLLEYBALL NATIONAL TEAMS 2020-2021 ATHLETE SELECTION PROCEDURES (Men and Women)

SITTING VOLLEYBALL NATIONAL TEAMS 2020-2021 ATHLETE SELECTION PROCEDURES (Men and Women) ELIGIBILITY FOR SITTING VOLLEYBALL NATIONAL TEAM In order to be eligible for selection to a National Team, all athletes must have a valid Canadian Passport as validation of Canadian Citizenship. Athletes must have a physical impairment that meets the classification standards for sitting volleyball as established by World ParaVolley (WPV). WPV is the international governing body for sitting volleyball. Athletes must meet the minimum eligibility requirements to participate in the Paralympic Games as set by the IPC, including having a confirmed classification status and be in good standing with WPV. Athletes must attend the Selection Camp* in order to be considered for selection to the National Team. An athlete who cannot attend the Selection Camp due to injury may be recommended for selection if he/she had previously been involved in the National Team. The athlete must receive the approval of the coaching staff and have written proof of medical reason for exclusion from the selection camp. Athletes must submit application for approval with medical note to the Para HP Manager or the High Performance Director - Sitting Volleyball prior to the Selection Camp. If an athlete’s injury does not prevent travel, it is expected that the athlete still attends selection camp and participates team off-court sessions. *With current COVID-19 restrictions, athletes will attend selection camp once it is safe to do so, all evaluations will be based on previous performance at camps and competitions SELECTION CRITERIA – NATIONAL TEAM MEMBER Athletes will be selected to a National Team program and rated within Volleyball Canada’s Gold Medal Profile (GMP) for Sitting Volleyball. -

Should Video Gaming Be a School Sport? Video Gaming Has Pro Teams, Star Players, and Millions of Fans

DEBATE IT! We Write It, You Decide Should Video Gaming Be a School Sport? Video gaming has pro teams, star players, and millions of fans. But should it be considered a sport, like basketball or track? JANUARY 6, 2020 By Anna Starecheski & Kathy Wilmore Illustration by James Yamasaki Excitement builds as a huge crowd waits for the tournament to begin. The bleachers are filled with friends and family wearing school colors and holding signs. When the teams enter and take their places, the crowd goes wild, stomping their feet and shouting out the names of their favorite players. But this isn’t a varsity football or basketball game—and the players aren’t on a field or a court. They’re teams of students sitting in front of computer monitors, clicking mice and tapping away at keyboards. At a growing number of schools around the country, video gaming has become a varsity team sport. From 2018 to 2019, the number of schools participating in the High School Esports League grew from about 200 to more than 1,200. Video game competitions, known as esports (for electronic sports), are even bigger on the world stage. Nearly 100 million people around the globe watched the 2018 League of Legends World Championship finals. That’s about the same number of people as watched the 2018 Super Bowl. As esports have become more popular, some people are pushing for gaming to be considered a school sport. After all, they say, games like Fortnite, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, and NBA 2K20 require skills and focus and can be intensely competitive. -

Box Lacrosse RULES

Madlax League and Tournament Box Lacrosse RULES Madlax Box Lax Classic Tournament - Specific Rules & Details: Box Lacrosse Rules – General Box Lacrosse penalties are announced by the official on the floor by raising his arm. Offensive team will have possession of the ball until the defensive team gains control of the ball. The Official will then stop play and escort player to the penalty box or award possession of the ball to offensive team. Box Lax Penalty Types: 1. Technical fouls (in the crease, loose ball push, interference, over & back, etc.) change ball possession. 2. Minor fouls (holding, high stick, hit from behind with possession, charging, minor slashing, etc.) -- 2:00 penalty (releasable). 3. Major fouls (severe slashing, unsportsmanlike conduct, BOARDING) -- 4:00 penalty (un-releasable). 4. Major misconduct (fighting, etc.) -- 10:00 penalty (un-releasable) and ejection. Mouthpieces are REQUIRED and Rib Pads & Hard Arm Pads are STRONGLY ENCOURAGED Clearing and Off-Sides You have 10 seconds to clear midline. Once the offensive team clears midline there is NO returning back behind the midline with ball. This rule is just like basketball. If the offensive team loses the ball in the defensive zone it is live until that team touches the ball. Defensive players can play that ball. Face-Offs All players who are NOT facing off stand behind the restraining line. The ball is live after whistle. Shot Clock We play a 30 second Shot Clock. In Dulles Sportsplex there are no shot clocks so referees use a 30 second timer with an audible buzzer. It works very well. -

3D BOX LACROSSE RULES

3d BOX LACROSSE RULES 3d BOX RULES INDEX BOX 3d.01 Playing Surface 3d.1 Goals / Nets 3d.2 Goal Creases 3d.3 Division of Floor 3d.4 Face-Off Spots 3d.5 Timer / Scorer Areas GAME TIMING 3d.6 Length of Game 3d.7 Intervals between quarters 3d.8 Game clock operations 3d.9 Officials’ Timeouts THE OFFICIALS 3d.10 Referees 3d.11 Timekeepers 3d.12 Scorers TEAMS 3d.13 Players on Floor 3d.14 Players in Uniform 3d.15 Captain of the Team 3d.16 Coaches EQUIPMENT 3d.17 The Ball 3d.18 Lacrosse Stick 3d.19 Goalie Stick Dimensions 3d.20 Lacrosse Stick Construction 3d.21 Protective Equipment / Pads 3d.22 Equipment Safety 3d.23 Goaltender Equipment PENALTY DEFINITIONS 3d.24 Tech. Penalties / Change of Possession 3d.25 Minor Penalties 3d.26 Major Penalties 3d.27 Misconduct Penalties 3d.28 Game Misconduct Penalty 3d.29 Match Penalty 3d.30 Penalty Shot FLOW OF THE GAME 3d.31 Facing at Center 3d.32 Positioning of all Players at Face-off 3d.33 Facing at other Face-off Spots 3d.34 10-Second count 3d.35 Back-Court Definition 3d.36 30-Second Shot Rule 3d.37 Out of Bounds 3d.38 Ball Caught in Stick or Equipment 3d.39 Ball out of Sight 3d.40 Ball Striking a Referee 3d.41 Goal Scored Definition 3d.42 No Goal 3d.43 Substitution 3d.44 Criteria for Delayed Penalty Stoppage INFRACTIONS 3d.45 Possession / Technical Infractions 3d.46 Offensive Screens / Picks / Blocks 3d.47 Handling the Ball 3d.48 Butt-Ending 3d.49 High-Sticking 3d.50 Illegal Cross-Checking 3d.51 Spearing 3d.52 Throwing the Stick 3d.53 Slashing 3d.54 Goal-Crease Violations 3d.55 Goalkeeper Privileges 3d.56