CSR in Swedish Football

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentation SGAF Engelska Lucie Le Gall

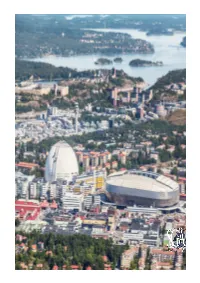

SGA Fastigheter Mats Viker SGA FASTIGHETER ° Owned by the City of Stockholm ° Ericsson Globe, Hovet, Annexet och Tele2 Arena ° SkyView and Tolv Stockholm ° 17 employes Tele2 Arena 2013 Capacity 30-45 000 visitors. Retractable roof Venue of the year 2014 Green Building Council ”Gold” Ericsson Globe (1989) Capacity 13 850 -16 500 visitors The largest spherical building in the world Maybe the most iconic building in the northern Europe https://youtu.be/vVfq-KKkis4 Hovet https://youtu.be/OCQWys1xmiQ 1955 Capacity 8-9 000 visitors. Annexet (1989) 1989 Originally part of the Ericsson Globe (warm up) Capacity - 3 500 visitors Sky View (2010) 2010 Tourist attraction Two gondolas 16 visitors each Capacity 150.000 visitors/year/år Tolv Stockholm (2013) 2013 12 000 m2 entertainment, bars, restaurant, night club 1,2 million visitors 2016 Quality Hotel Globe 527 rooms Private investment Shopping mall 60 shops 10 restaurants and bars Private investment Offices 80 000 Sq m offices Private investment ACCESS 1,5 million people within 1 hour 6 underground stations within 1 km 2 city tram stations, Globen and Gullmarsplan 40-50 buslines to the southern suburbs at Gullmarsplan Close to E4/E20 2500 indoor parking and 2500 outdoor 1000 places for bicycles LARGEST EVENT AREA IN SCANDINAVIA 2014-03-06 Sida 14 LARGEST EVENT AREA IN SCANDINAVIA 100 80 60 78 77 64 1 AREA 40 52 20 4 ARENAS 0 Ericsson Hovet Annexet Tele2 Globe Arena 1 TOURIST ATTRACTION 300 EVENTS/YEAR 52 69 Concert 2 000 000 VISITORS/YEAR Family 24 Home team 23 4 TEAMS Other sport Business -

Analys Av Allsvenskans Ekonomi 1997

Analys av Damallsvenska klubbarnas ekonomi 2010 Svenska Fotbollförbundet Jessica Palm Innehåll Sammanfattning ....................................................................................................................... 3 Inledning ................................................................................................................................... 5 Damallsvenska klubbarnas resultat ....................................................................................... 5 Damallsvenska klubbarnas intäkter ....................................................................................... 7 Damallsvenska klubbars kostnader ........................................................................................ 9 Damallsvenska klubbarnas egna kapital och soliditet ........................................................ 12 Elitlicensens regler i korthet .................................................................................................. 13 Samband mellan klubbarnas kostnader och tabellposition ............................................... 14 Sida 2 (14) Analys av Damallsvenska klubbarnas ekonomi 2010 Sammanfattning Under 2010 har de Damallsvenska klubbarna minskat sina kostnader med 8 %, även intäkterna har minskat med 3 %. Klubbarna i Damallsvenskan redovisade år 2010 sammantaget ett underskott uppgående till -2 672 tkr (2009: -6 338 tkr), vilket var en klar förbättring jämfört med året innan. Man kan konstatera att minskade kostnader samt en mindre intäktsminskning har lett till bättre ekonomiskt -

Djurgården Stockholm – Idrott Och Samhällsnytta I Förening

Djurgården Stockholm – Idrott och samhällsnytta i förening © 2013 Djurgården Fotboll • Filip Lundberg [email protected] • fi[email protected] Grafisk Form: Formination AB • Tryck: Wallén Grafiska Förord PROJEKTANSVARIG FILIP LUNDBERG Fil. mag. statsvetenskap Filinfo Den här sammanställningen är efterfrågad av Djurgården Fotboll i syfte att påvisa de stora sociala och ekonomiska mervärden som för- eningen genom sin verksamhet bidrar med i Stockholm. Vid ett seminarium nyligen, om hur man bäst kan utveckla svensk fotboll, sade även Svensk Elitfotbolls generalsekreterare Mats En- quist att man inte ska fokusera alltför mycket på att vinna, utan att istället fokusera på att sätta sig i en position där man kan vinna. Det finns inga genvägar. Applicerat på det här projektet handlar det allt- så inte om att säga att det är si eller så utan att skapa sig en position där man blir lyssnad på, och erkänd som den positiva samhällskraft man faktiskt är. Först då kan svensk fotbolls hela potential uppnås. Steg för steg. Den här sammanställningen är lika mycket en inventering av vad som redan görs, som en fingervisning om vad som kan uppnås till- sammans med idrottens aktörer, i samverkan med offentlig och pri- vat sektor. De intervjuade har olika bakgrund inom statsvetenskap, historia, näringsliv, ekonomi och integration/ungdom samt med ett gemen- samt intresse för idrottens relation till respektive ämnesområde. Även personer ”närmare” verksamheten har inbegripits för att täcka in fler perspektiv. Tack till alla som ställt upp och diskuterat de här frågorna. Extra stort tack till Björn Anders Larsson från Idrottsekonomiskt centrum i Lund som förutom intervjun också bidragit med avsnittet ”Opti- mering av värdeskapande” samt bilagan ”Idrottens sociala och civila kapital”, för den som vill veta lite mer. -

420 Serien B

Checklist 420 serien Multisport 1958 1 Sven Davidson AIK, Tennis 2 Emil Zatopek Tjeckoslovakien, Friidrott 3 Erik Uddebom Bromma IF, Friidrott 4 Knut Fredriksson IK Favör, Friidrott 5 Chris Chataway England, Fridrott 6 Sven-Ove Svensson Hälsingborgs IF, Fotboll 7 Sven Eliasson Waggeryds IK, Fotboll 8 Åke Johansson IFK Norrköping, Fotboll 9 Axel Grönberg BK Athen, Brottning 10 Curt Cahlman Sandvikens IF, Fotboll 11 Karl-Alfred Jakobsson GAIS, Fotboll 12 Nils Håkansson Halmstads BK, Fotboll 13 Sven "Tumba" Johansson Djurgårdens IF, Ishockey 14 Ragnar Lundberg IFK Södertälje, Friidrott 15 Sixten Jernberg Lima IF, Skidor 16 Audun Boysen Norge, Friidrott 17 Karl-Gösta Johnson IF Göta, Friidrott 18 Gunnar Nielsen Danmark, Friidrott 19 Lennart Larsson SK Järven Skidor 20 Per-Olof Östrand Hofors AIF, Simning 21 Lennart Nilsson Waggeryds IK, Fotboll 22 Holger Hansson IFK Göteborg, Fotboll 23 Inge Blomberg IFK Malmö, Fotboll 24 Rolf Gottfridsson IFK Göteborg, Friidrott 25 Evert Nyberg Örgryte IS, Friidrott 26 Lars Hindmar Malmö AI, Friidrott 27 Sandor Rozsnyoi Ungern, Friidrott 28 Sigge Ericsson IF Castor, Skridsko 29 Ingemar Johansson Göteborg, Boxning 30 Sonja Edström Luleå SK, Skidor 31 Karin Larsson SK Ran, Simning 32 Sten Ericksson IF Elfsborg, Friidrott 33 Bertil Karlsson Hälsingborgs IF, Fotboll 34 Carl-Eric Stockenberg IFK Borås, Handboll 35 John Landy Australien, Friidrott 36 Per-Arne Berglund IF Start, Friidrott 37 Vladimir Kutz Sovjet, Friidrott 38 Birger Asplund IF Castor, Friidrott 39 Gösta Brännström Skellefteå AIK, Friidrott 40 Sune -

Jay-Z and Beyoncé Join Forces for Otr Ii Tour

JAY-Z AND BEYONCÉ JOIN FORCES FOR OTR II TOUR – Stadium Tour Kicks Off in UK & Europe on June 6; North American Leg Starts July 25th – – Citi, TIDAL, and Beyhive Pre-sales Begin March 14th – – Tickets On Sale to General Public Starting March 19th at LiveNation.com – LOS ANGELES, CA (Monday, March 12, 2018) – JAY-Z AND BEYONCÉ are joining forces for the newly announced OTR II stadium tour. Kicking off Wednesday, June 6th in Cardiff, UK, the international outing will stop in 15 cities across the UK and Europe and 21 cities in North America. The full itinerary can be found below. The tour is presented by Live Nation Global Touring in association with Parkwood Entertainment and Roc Nation. Tickets will go on sale to the general public starting Monday, March 19th at LiveNation.com and all usual outlets. On-sale dates and times vary (full on-sale schedule provided below). Citi is the official credit card for the OTR II stadium tour and as such, Citi cardmembers can take advantage of a special pre-sale opportunity for show dates in the United States, Europe and the UK. For performances going on sale on Monday, March 19th in the US and Europe, Citi cardmembers may purchase tickets beginning Wednesday March 14th at noon through Saturday, March 17th at 5pm (Citi pre-sale in Paris ends Friday, March 16th at 6pm). For concerts in the United Kingdom, Sweden and Poland, Citi cardmembers may access tickets starting Monday, March 19th at noon through Thursday, March 22nd at 5pm prior to the general on-sale on Friday, March 23rd. -

Aktiebolag Inom Svensk Elitfotboll

Aktiebolag inom svensk elitfotboll Jyri Backman Idrottsvetenskap, Malmö högskola Publicerad på Internet, www.idrottsforum.org/articles/backman/backman090408.html (ISSN 1652–7224), 2009–04–08 Copyright © Jyri Backman 2009. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. Idrott och pengar – det har hänt mycket sedan nyss bortgångne Arne Andersson till- sammans med Gunder Hägg och andra i mitten av 40-talet stängdes av på livstid för brott mot amatörreglerna, det vill säga för att ha tagit emot pengar för sin idrottsliga verksamhet. Sedan dess, och framför allt sedan den televiserade sporten slog igenom på 70-talet, har en nästan ofattbar utveckling ägt rum när det gäller sportens kommersi- alisering. Här kan man tala om symbios – från början fakultativ men nu närmast obligat; för många företag är sporten det främsta annonsutrymmet, och många idrotter skulle i grunden förändras utan kapitaltillförseln i form av sponsors- och reklampengar. Kring denna ömsesidigt fördelaktiga relation har en hel serviceindustri växt upp; forumet mot- tar dagligen två separata nyhetsbrev från London, som informerar om olika aspekter av de praktiska applikationerna kring sport och pengar. Företagen bakom gör avancerade analyser som till hutlösa priser säljs till hugade blivande sponsorer. Också i Sverige finns ett par sådana serviceföretag. Numera handlar många nyheter om sponsring som frusit fast i kristiden, eller om sponsorer som ertappats som ekonomiska brottslingar. -

Sportification and Transforming of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’S Football, 1966-1999

Equalize it!: Sportification and Transforming of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966-1999 Downloaded from: https://research.chalmers.se, 2021-09-30 11:41 UTC Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Svensson, D., Oppenheim, F. (2018) Equalize it!: Sportification and Transforming of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966-1999 The International journal of the history of sport, 35(6): 575-590 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2018.1543273 N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. research.chalmers.se offers the possibility of retrieving research publications produced at Chalmers University of Technology. It covers all kind of research output: articles, dissertations, conference papers, reports etc. since 2004. research.chalmers.se is administrated and maintained by Chalmers Library (article starts on next page) The International Journal of the History of Sport ISSN: 0952-3367 (Print) 1743-9035 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fhsp20 Equalize It!: ‘Sportification’ and the Transformation of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966–1999 Daniel Svensson & Florence Oppenheim To cite this article: Daniel Svensson & Florence Oppenheim (2019): Equalize It!: ‘Sportification’ and the Transformation of Gender Boundaries in Emerging Swedish Women’s Football, 1966–1999, The International Journal of the History of Sport, DOI: 10.1080/09523367.2018.1543273 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2018.1543273 -

20 Football Clubs to Participate in the Second Season of Eallsvenskan

20 Football Clubs To Participate in The Second Season of eAllsvenskan eAllsvenskan is a part of EA SPORTS FIFA 20 Global Series Total Prize Pool for Season 2 Exceeds $41,000 STOCKHOLM — DreamHack, the premier gaming lifestyle festival, and Svensk Elitfotboll (SEF) announced today the second season of eAllsvenskan, the largest professional FIFA competition in Sweden. The new season is set to start on March 10 and will feature an increased number of participating teams, a new format, and increased possibilities to watch the games. Reigning eAllsvenskan champions Malmö FF will defend their title against 19 additional football clubs with the new additions including Degerfors IF, IF Elfsborg, Kalmar FF, IFK Norrköping, Norrby IF, IK Sirius, Trelleborgs FF, Västerås SK, and Östers IF. The newcomers are joined by returning teams AIK, Djurgårdens IF, AFC Eskilstuna, Hammarby IF, Helsingsborgs IF, BK Häcken, J-Södra, Malmö FF, GIF Sundsvall, Örgryte IS, and Örebro SK. Participating teams will consist of at least two professional FIFA players that will try to secure the title during the season finals set to take place during the second weekend of May. “The first edition of eAllsvenskan did set a new standard for what competitive FIFA could be in Sweden,” said Niclas Jansson, Head of Digital at Svensk Elitfollboll. “It feels great that we’re back, following some tinkering, with a new and improved season.” “The FIFA esports scene continue to grow every year and eAllsvenskan is definitely the championship for football club teams in Sweden. The second season will feature 20 clubs and it is broadcasted on several platforms where gamers have a presence,” said Marcus Lindmark, co-CEO at DreamHack. -

Säsongen 2020

SÄSONGEN 2020 Unicoach – Säsongen 2020 1 INNEHÅLLSFÖRTECKNING Unicoach och Certifieringen 2020 � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 3 SUPERETTAN 2020 � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �71 Unicoach 2020 – � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 4 AFC Eskilstuna � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 72 Akropolis IF � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 74 Tabeller och resultat 2020 � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 5 Dalkurd FF � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 75 Certifieringen 2020 � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 Degerfors IF � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 76 Certifierare � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 GAIS � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 78 Certifieringens syfte � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 6 GIF Sundsvall � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �80 Verksamhetsområden � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 7 Halmstads BK � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 82 Nya deltagande klubbar � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 8 IK Brage � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �84 Grundkrav för deltagande � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 8 Jönköpings Södra IF � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 86 -

Inbjudan Till Teckning Av Aktier I AIK Fotboll AB (Publ)

Inbjudan till teckning av aktier i AIK Fotboll AB (publ) Nyemission 2011 Erbjudandet i sammandrag Handlingar införlivade genom Företrädesrätt hänvisning Fem (5) befintliga aktier av serie A ger rätt att teckna Detta prospekt består av, utöver föreliggande doku åtta (8) nya aktier av serie A. Fem (5) befintliga aktier av ment, följande handlingar som härmed införlivas i serie B ger rätt att teckna åtta (8) nya aktier av serie B prospektet genom hänvisning: Teckningsrätter – Delårsrapport för januari–september 2010. Del För varje aktie av serie A som innehas på avstämnings årsrapporten har översiktligt granskats av Bolagets dagen erhålls åtta (8) teckningsrätter av serie A och revisor. för varje aktie av serie B som innehas på avstämnings dagen erhålls åtta (8) teckningsrätter av serie B. Fem – Bolagets årsredovisningar avseende räkenskapsåren (5) teckningsrätter av serie A berättigar till teckning av 2007, 2008 och 2009. Årsredovisningarna har en (1) ny aktie av serie A och fem (5) teckningsrätter reviderats av Bolagets revisor. Hänvisningen avser av serie B berättigar till teckning av en (1) ny aktie av endast historisk finansiell information inklusive serie B förvaltningsberättelser, noter och revisionsberättel ser på sid 13–30 i årsredovisningen för 2007, sid Teckningskurs 17–38 i årsredovisningen för 2008 samt sid 25–43 1,50 SEK per aktie i årsredovisningen för 2009. Emissionsbelopp: Prospektet samt ovanstående handlingar kommer Cirka 20,2 MSEK under prospektets giltighetstid att finnas tillgängliga på AIK:s hemsida (www.aikfotboll.se). Avstämningsdag 17 januari 2011. Sista dag för handel i AIK:s Baktie Definitioner med rätt att delta i nyemissionen är den 12 januari Med “AIK” eller “Bolaget” avses i detta prospekt AIK 2011 Fotboll AB (publ), org nr 5565201190, eller beroen de på sammanhang, den koncern i vilken AIK Fotboll Teckning genom betalning AB (publ) är moderbolag. -

Scandinavian Women's Football Goes Global – a Cross-National Study Of

Scandinavian women’s football goes global – A cross-national study of sport labour migration as challenge and opportunity for Nordic civil society Project relevance Women‟s football stands out as an important subject for sports studies as well as social sciences for various reasons. First of all women‟s football is an important social phenomenon that has seen steady growth in all Nordic countries.1 Historically, the Scandinavian countries have been pioneers for women‟s football, and today Scandinavia forms a centre for women‟s football globally.2 During the last decades an increasing number of female players from various countries have migrated to Scandinavian football clubs. Secondly the novel development of immigration into Scandinavian women‟s football is an intriguing example of the ways in which processes of globalization, professionalization and commercialization provide new challenges and opportunities for the Nordic civil society model of sports. According to this model sports are organised in local clubs, driven by volunteers, and built on ideals such as contributing to social cohesion in society.3 The question is now whether this civil society model is simply disappearing, or there are interesting lessons to be drawn from the ways in which local football clubs enter the global market, combine voluntarism and professionalism, idealism and commercialism and integrate new groups in the clubs? Thirdly, even if migrant players stay only temporarily in Scandinavian women‟s football clubs, their stay can create new challenges with regard to their integration into Nordic civil society. For participants, fans and politicians alike, sport appears to have an important role to play in the success or failure of the integration of migrant groups.4 Unsuccessful integration of foreign players can lead to xenophobic feelings, where the „foreigner‟ is seen as an intruder that pollutes the close social cohesion on a sports team or in a club. -

Allsvensk Bandy Missa Inte Ale-Surte Bk’S I Ale Arena Hemmamatcher! Lördag 26 December Kl 13.15 Ale-Surte Bk Vs

2009 | vecka 52 | nummer 46 | alekuriren SPORT 27 BANDY Allsvenska södra Ale-Surte – Gais 4-3 (3-1) Mål Ale-Surte: Johan Malmqvist 2, Matthias Andersson och Joakim Ale-Surte nya serieledare Strömbäck 1 vardera. Matchens kurrar: Alexander Wetterberg 3, FRILLESÅS. Ale-Surte för sig, men Frillesås kämpa- Joakim Strömbäck 2, Johan Malm- är ny serieledare i all- de tappert. Den hemvändande qvist 1. svenskans södergrupp. skyttekungen, Lasse Karls- Lördagens triumf son, var dock på målgörar- Frillesås – Ale-Surte 2-5 (1-2) borta mot Frillesås humör och noterades för fyra Mål Ale-Surte: Lasse Karlsson 4, skickade laget i topp. fullträffar. Kalle Ahlgren. Matchens kurrar: Lasse Karlsson 3, På Annandag jul – Vi gör en stabil insats och väntar Gripen och nu ser vi verkligen att defensi- ven sitter. Får vi fart på Lasses Ale-Surte 8 10 12 arrangören vädrar fullt Boltic 8 17 11 hus. och Grahns målskytte blir vi svårslagna, menar Urban Gripen 8 7 11 Från Trollhättan väntas minst Aheinen. Gais 8 11 10 sex bussar med bandyfrälsta Gripen på Annandag jul blir Motala 8 7 10 entusiaster. Det kan bli lapp en klassiker. Det skiljer bara en Stjärnan 7 0 7 på luckan och Ale-Surte har poäng mellan lagen och mat- Jönköping 8 -12 7 därför ordnat förköp. chen kan bli avgörande för se- Otterbäcken 7 -2 6 – Person- riens utgång. Lidköping 8 -11 6 ligen hoppas BANDY Alexander Frillesås 8 -9 5 jag på 1500 Mayborn som Tranås 8 -11 5 Allsvenskan södra, 16/12 åskådare. Det är tillbaka i Nässjö 8 -7 4 Frillesås – Ale-Surte 3-5 (1-2) är ett klas- Trollhättan siskt möte i en efter en sejour HANDBOLL match som gäller en hel del.