PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

Bremen Und Die Kunst in Der Kolonialzeit

DER BLINDE FLECK BREMEN UND DIE KUNST IN DER KOLONIALZEIT THE BLIND SPOT BREMEN, COLONIALISM AND ART EDITED BY JULIA BINTER ©2017byKunsthalle Bremen –Der Kunstverein in Bremen www.kunsthalle-bremen.de ©2017byDietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH, Berlin www.reimer-mann-verlag.de Funded by the International MuseumFellowship program of the German Federal Cultural Foundaition In cooperation with Afrika-Netzwerk Bremen e.V. Bibliographic Information of the German National Library Deutsche Nationalbibliothek holds arecordofthis publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographical data can be found under: http://dnb.d-nb.de. All rightsreserved. No partofthis book maybereprintedorrepro- ducedorutilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, nowknown or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrievalsystem, without permission in writing from the publishers. ISBN 978-3-496-01592-5 With contributions by Julia Binter Anna Brus Anujah Fernando Anna Greve HewLocke YvetteMutumba Ngozi Schommers Vivan Sundaram Translations from German and English by Daniel Stevens Lenders Nolde-Stiftung Seebüll Sammlung Vivanund Navina Sundaram Sammlung Karl H. Knauf,Berlin Übersee-Museum Bremen Deutsches Schifffahrtsmuseum Bremerhaven Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg Focke-Museum Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte Schulmuseum Bremen Landesfilmarchiv Bremen Intro Ⅰ Kawanabe Kyōsai, The Lazy one in the Middle, n. d., monochrome woodcut, Outro Ⅰ Kunsthalle Bremen – Artist unknown, -

University of Tarty Faculty of Philosophy Department of History

UNIVERSITY OF TARTY FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY LINDA KALJUNDI Waiting for the Barbarians: The Imagery, Dynamics and Functions of the Other in Northern German Missionary Chronicles, 11th – Early 13th Centuries. The Gestae Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum of Adam of Bremen, Chronica Slavorum of Helmold of Bosau, Chronica Slavorum of Arnold of Lübeck, and Chronicon Livoniae of Henry of Livonia Master’s Thesis Supervisor: MA Marek Tamm, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales / University of Tartu Second supervisor: PhD Anti Selart University of Tartu TARTU 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 I HISTORICAL CONTEXTS AND INTERTEXTS 5 I.1 THE SOURCE MATERIAL 5 I.2. THE DILATATIO OF LATIN CHRISTIANITY: THE MISSION TO THE NORTH FROM THE NINTH UNTIL EARLY THIRTEENTH CENTURIES 28 I.3 NATIONAL TRAGEDIES, MISSIONARY WARS, CRUSADES, OR COLONISATION: TRADITIONAL AND MODERN PATTERNS IN HISTORIOGRAPHY 36 I.4 THE LEGATIO IN GENTES IN THE NORTH: THE MAKING OF A TRADITION 39 I.5 THE OTHER 46 II TO DISCOVER 52 I.1 ADAM OF BREMEN, GESTA HAMMABURGENSIS ECCLESIAE PONTIFICUM 52 PERSONAE 55 LOCI 67 II.2 HELMOLD OF BOSAU, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 73 PERSONAE 74 LOCI 81 II.3 ARNOLD OF LÜBECK, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 86 PERSONAE 87 LOCI 89 II.4 HENRY OF LIVONIA, CHRONICON LIVONIAE 93 PERSONAE 93 LOCI 102 III TO CONQUER 105 III.1 ADAM OF BREMEN, GESTA HAMMABURGENSIS ECCLESIAE PONTIFICUM 107 PERSONAE 108 LOCI 128 III.2 HELMOLD OF BOSAU, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 134 PERSONAE 135 LOCI 151 III.3 ARNOLD OF LÜBECK, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 160 PERSONAE 160 LOCI 169 III.4 HENRY OF LIVONIA, CHRONICON LIVONIAE 174 PERSONAE 175 LOCI 197 SOME CONCLUDING REMARKS 207 BIBLIOGRAPHY 210 RESÜMEE 226 APPENDIX 2 Introduction The following thesis discusses the image of the Slavic, Nordic, and Baltic peoples and lands as the Other in the historical writing of the Northern mission. -

Digheds Og Den Hellige Martyr Lucius' Kirke

b k 5 \ DET KONGELIGE BIBLIOTEK DA 1.-2.S 34 II 8° 1 1 34 2 8 02033 9 ft:-' W/' ; ■■ pr* r ! i L*•' i * •! 1 l* 1*. ..«/Y * ' * !■ k ; s, - r*r ' •t'; ;'r rf’ J ■{'ti i ir ; • , ' V. ■ - •'., ■ • xOxxvX: ■ yxxf xXvy.x :■ ■ -XV' xxXX VY, XXX YXYYYyØVø YY- afe ■ .v;X' p a V i %?'&ø :■" \ . ' :•!■• ,-,,r*-„f.>/r'. .. ‘m.;.;- • 7.- .; 7.. \ v ;»WV X '• • ø •'>; ^/■•.,:. i ■-/.. ,--.v ■,,'--- ;X:/. - V '-■■. <V;:S'. ■ V ;>:X.>. - . / : r- :. • • • v •'•<.•.'•„.'«;•••■ • : ø ø r - 0 0 ^ 0 ^ , ' . i* n ‘-:---yri ' *•1 Y v - ^ y ' xv • v^o^.1. •’". '.. ' ^ ^ - ■ ■ *: . ‘4 V • : Vi.'-* ' •• , -py » » r S * . ., v- - Y,■ x.: ■■■ '/ ■. '-^;-v•:■■'•:. I , /■ ... \ < y : - j _ _ ^ . '. • vV'V'-WC'/:i .. • .' - '■V ^ -V X X i ■:•*'• -fåk=, ’å«! r “\ > VéS' V: m;. ^ S -T 'l ' é Æ rs^l K»s£-^v;å8gSi;.:v ,V i: ,®%R m r t m •'. * ‘ • iW . - ' * •’ ' ''*- ’-' - - • • 7« ' - “'' ' ’ i ' l ø ^ i j : j I 0 - + ! f- .. i 1 v s . j.. •; ■''■ - - . ' • < •‘ . ( . :/Æ m .‘-\ ^ • • v ; ;-• ,ti , ’- É p Æ f s . - f./'T-i :\ . :■.:érijid \*| ^ i ? S \ ■!- X.-3 I M«i; .•• ./;,X $ii«M c '>^w xhr-.vX . - " ' . v - x ^ P 3X.V ,v '■'/■ :■ 1 ■'■■I ; /# 1'..: \ ; . ?.. >>■>. ;; !a - ; : i : ■ •■ vrd-^i.■■■: v .^ > ;', v \ . ; ^ .1. .,*.-• •-• — » . ‘ -,-\ ■'£ vV7 -u-' "*■- ;' ' v ' ;i'»1 '••-■^ .VV ’ i rr^— 7— -X r- ••r-’arjr . • 4 i.1-’ 1 ^ • — ^.ft ... <t ' i v - ^ '-» 1 ■ .■ ■ T* • \ > .• •■,.■ ;- : . ; . ^ ' ■ I M r^-^Tør^r- 0 "^: ør.:,ø^n>w^: ■■'^nw'<$:fi&rrTi A w ; :• v ' .:”. 1 i.- V V ' ' «‘v >»?•-•.-. ' -...■i iWl••••. ? .•”■ /•<. • ^ ■ •* ' '/■:■ , '■'/■ ,- ' . •> . ^ . ’ • ,v :■ ■?. • ;■ • . ‘ ' ' ' ' . •.i* L*4 V v’ f. * v-.-iV-, iU ' . -

Approaches to Community and Otherness in the Late Merovingian and Early Carolingian Periods

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by White Rose E-theses Online Approaches to Community and Otherness in the Late Merovingian and Early Carolingian Periods Richard Christopher Broome Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2014 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Richard Christopher Broome to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2014 The University of Leeds and Richard Christopher Broome iii Acknowledgements There are many people without whom this thesis would not have been possible. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Ian Wood, who has been a constant source of invaluable knowledge, advice and guidance, and who invited me to take on the project which evolved into this thesis. The project he offered me came with a substantial bursary, for which I am grateful to HERA and the Cultural Memory and the Resources of the Past project with which I have been involved. Second, I would like to thank all those who were also involved in CMRP for their various thoughts on my research, especially Clemens Gantner for guiding me through the world of eighth-century Italy, to Helmut Reimitz for sending me a pre-print copy of his forthcoming book, and to Graeme Ward for his thoughts on Aquitanian matters. -

November 5, 2017

November 5, 2017 The mission of The First Presbyterian Church in Germantown is to reflect the loving presence of Christ as we serve others faithfully, worship God joyfully and share life together in a diverse and generous community. In preparation for worship please take the opportunity to speak silently to God. At the close of the service let us greet one another with cheerfulness. Please be sure that your cell phone is turned off during worship. November 5, 2017 Twenty-second Sunday after Pentecost ORDER OF MORNING WORSHIP AT 10:00 AM GATHERING AS GOD’S FAMILY Prelude: From Eleven Chorale Preludes, Op. 122 Joannes Brahms O How Blest Are Ye Whose Toils Are Ended Deck Thyself, My Soul, with Gladness Welcome and Announcements Minute for Stewardship Faith Wolford Introit: Come to Zion (Shaker melody) Ted W. Barr Come to Zion sin sick souls in sorrow bound. Lay your cares upon the altar where true healing may be found. Shout Alleluia, alleluia! Praise resounds o’er land and sea. All who will may come and share the glories of this jubilee. †*Call to Worship From Psalm 107 Leader: O give thanks to the Lord, for he is good; for his steadfast love endures forever. People: Let the redeemed of the Lord say so, those he redeemed from trouble. Leader: Some wandered in desert wastes, finding no way to an inhabited town; hungry and thirsty, their soul fainted within them. People: Then they cried to the Lord in their trouble, and he delivered them from their distress. Leader: He led them by a straight way, until they reached an inhabited town. -

The Church As Koinonia of Salvation: Its Structures and Ministries

THE CHURCH AS KOINONIA OF SALVATION: ITS STRUCTURES AND MINISTRIES Common Statement of the Tenth Round of the U.S. Lutheran-Roman Catholic Dialogue THE CHURCH AS KOINONIA OF SALVATION: ITS STRUCTURES AND MINISTRIES Page ii Preface It is a joy to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification (JDDJ), signed by representatives of the Catholic Church and the churches of the Lutheran World Federation in 1999. Pope John Paul II and the leaders of the Lutheran World Federation recognize this agreement as a milestone and model on the road toward visible unity among Christians. It is therefore with great joy that we present to the leadership and members of our churches this text, the tenth produced by our United States dialogue, as a further contribution to this careful and gradual process of reconciliation. We hope that it will serve to enhance our communion and deepen our mutual understanding. Catholics and Lutherans are able to “confess: By grace alone, in faith in Christ’s saving work and not because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works” (JDDJ §15). We also recognize together that: “Our consensus in basic truths of the doctrine of justification must come to influence the life and teachings of our churches. Here it must prove itself. In this respect, there are still questions of varying importance which need further clarification” (JDDJ §43). In this spirit we offer the following modest clarifications and proposals. -

ENG Flyer Bearbeitet Quer Spalten

Adalbert (two semicircular windows and a round one, ……………………………………………………………………………. Museum of Christian art and Romanesque, second half of the 11th century, partly 3 The front-room of the first floor is dedicated to the the history of the church of Bremen restored). history and significance of the Bremen bishopric from www.dommuseum-bremen.de its foundation in 787 to its disintegration in 1648. As a ……………………………………………………………………………. Now we are in a Romanesque room of the 13th matter of course, only some selected items could be century. The fresco painting was discovered under emphasized e.g. Bremen bishops as missionaries and dirty plaster layers during the last reconstructions. saints (Willehad, Ansgar, Rimbert and Unni); Adalbert WELCOME TO After careful uncovering, consolidation and as a politician and Archbishop; Bremen as a center of THE DOM-MUSEUM! restoration four pictures can be recognized among rich mission for Northern Europe (“Rome of the North”); ornaments of tendrils and inserted heads of angels. In music of the early Middle Ages in Bremen; documents the entrance bay Christ’s Baptism in the Jordan; in the and seals of Bremen bishops; history of the Cathedral Highlights center, on opposite sides, in fragments only, the parish after the Reformation. • Historical textiles (mitre etc.) soldiers quarreling for the coat, and the Descent from • Crook of Limoges the Cross; on the narrower wall of the room the It is understandable that the attention of the visitors is • Bremen – „Rome of the North“ presentation of Christ in the mandorla, called Maiestas attracted by the silver goods exhibited in the center; • Voluntary commitment as a living tradition Domini. -

Die Anfänge (782-96

Die Anfänge (782-96 Die Anfänge von Bistum und Stadt Bremen "Als die Römer frech geworden, zogen sie nach Deutschlands Norden“, so heißt es in einem Lied. Das prahlt damit, dass die Römer es dann mit Arminius, dem Cherusker, zu tun bekommen. Und der bereitet dem römischen Feldherrn Varus mit seinen Kohorten irgendwo am Teutoburger Wald eine herbe Niederlage. Nur die Germanennachkömmlinge im 19. Jahrhundert merkten augenscheinlich nicht, dass der Sieg im Jahr 9 nach Chr. ein Pyrrhussieg war, hätten sie den Arminius sonst durch das bombastische Hermannsdenkmal geehrt? Zwar besiegten die alten Germanen die damalige Weltmacht Rom, nur bezahlten sie mit ihrem Sieg dafür, dass sie weit über ein halbes Jahrtausend vom kulturellen und zivilisatorischen Fortschritt abgeschnitten waren. Denn Rom stand damals für Fortschritt. Es gab Steinhäuser, Toiletten mit fließendem Wasser, Theaterbauten, Literatur und anderes mehr… . In die Gegend von Bremen, präziser in den Wigmodigau, kommen Kultur, Zivilisation und Bildung daher erst in der zweiten Hälfte des 8. Jahrhunderts im Schlepptau des angelsächsischen Missionars Willehad. Der schlägt sich zu den widerborstigen Sachsen durch, weil er ihnen die Frohe Botschaft des Christentums verkünden will. Der Mann aus York muss ein gradliniger Mann gewesen sein, denn eine missglückte Hinrichtung in der Provinz Drente und der spätere Mord seiner Gefährten in Bremen anno 782, lässt ihn nicht ins heimische England zurückkehren, er geht vielmehr geradewegs zu den Sachsen. Das musste schief gehen. Ging es auch, zumindest im ersten Anlauf. Die Sachsen wollten keine Christen werden, daher erschlagen sie anno 782 „Gerval und Genossen“. Das bringt Bremen in ein schlechtes Licht, wird sein Start in Geschichte wie Kirchengeschichte doch so unauslöschlich mit einer Bluttat in Verbindung gebracht. -

The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 Ii Introduction Introduction Iii

Introduction i The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 ii Introduction Introduction iii The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930 –1965 Michael Phayer INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington and Indianapolis iv Introduction This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://www.indiana.edu/~iupress Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2000 by John Michael Phayer All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and re- cording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of Ameri- can University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Perma- nence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Phayer, Michael, date. The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 / Michael Phayer. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-253-33725-9 (alk. paper) 1. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958—Relations with Jews. 2. Judaism —Relations—Catholic Church. 3. Catholic Church—Relations— Judaism. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945) 5. World War, 1939– 1945—Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 6. Christianity and an- tisemitism—History—20th century. I. Title. BX1378 .P49 2000 282'.09'044—dc21 99-087415 ISBN 0-253-21471-8 (pbk.) 2 3 4 5 6 05 04 03 02 01 Introduction v C O N T E N T S Acknowledgments ix Introduction xi 1. -

Romanesque Architecture and Its Artistry in Central Europe, 900-1300

Romanesque Architecture and its Artistry in Central Europe, 900-1300 Romanesque Architecture and its Artistry in Central Europe, 900-1300: A Descriptive, Illustrated Analysis of the Style as it Pertains to Castle and Church Architecture By Herbert Schutz Romanesque Architecture and its Artistry in Central Europe, 900-1300: A Descriptive, Illustrated Analysis of the Style as it Pertains to Castle and Church Architecture, by Herbert Schutz This book first published 2011 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2011 by Herbert Schutz All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2658-8, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2658-7 To Barbara TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix List of Maps........................................................................................... xxxv Acknowledgements ............................................................................. xxxvii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One................................................................................................ -

Allfatherparadox Preview.Pdf

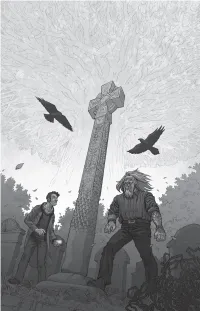

VIKINGVERSE: The All Father Paradox Outland Entertainment | www.outlandentertainment.com Founder/Creative Director: Jeremy D. Mohler Editor-in-Chief: Alana Joli Abbott Publisher: Melanie R. Meadors Senior Editor: Gwendolyn Nix The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or fictitious recreations of actual historical persons. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the authors unless otherwise specified. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Published by Outland Entertainment 5601 NW 25th Street Topeka KS, 66618 ISBN: 978-1-947659-52-0 Worldwide Rights Created in the United States of America Editor: Shannon Page Cover Illustration: Jeremy D. Mohler Cover Design and Interior Layout: STK•Kreations For my wife, who has Thiassi’s Eyes EXEGESIS I GOSFORTH, ENGLAND 2017 ELL, YOU TOOK YOUR TIME!” e roaring complaint was so unexpected that Churchwarden WMichaels dropped his freshly printed parish circulars. e gale swept them up and chased them across the churchyard, pink sheets apping between the moss-bound tombstones, like confetti at a gi- ant’s wedding. “Jesus!” Michaels scrabbled on the worn slate oor, preferring to salvage his photocopies over his dignity. ere was little hope of either. e coastal winds were merciless in winter and howled at the churchwarden in derision. He gave up and watched the last of his newsletters wing their way across the countryside to roost in far- distant hedgerows.