Downloaded on 2018-08-23T18:10:12Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion

Chapter 3 Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion 1 Introduction: Adam of Bremen and His Work “A. minimus sanctae Bremensis ecclesiae canonicus”1 – in this humble manner, Adam of Bremen introduced himself on the pages of Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, yet his name did not sink into oblivion. We know it thanks to a chronicler, Helmold of Bosau,2 who had a very high opinion of the Master of Bremen’s work, and after nearly a century decided to follow it as a model. Scholarship has awarded Adam of Bremen not only with a significant place among 11th-c. writers, but also in the whole period of the Latin Middle Ages.3 The historiographic genre of his work, a history of a bishopric, was devel- oped on a larger scale only after the end of the famous conflict on investiture between the papacy and the empire. The very appearance of this trend in histo- riography was a result of an increase in institutional subjectivity of the particu- lar Church.4 In the case of the environment of the cathedral in Bremen, one can even say that this phenomenon could be observed at least half a century 1 Adam, [Praefatio]. This manner of humble servant refers to St. Paul’s writing e.g. Eph 3:8; 1 Cor 15:9, and to some extent it seems to be an allusion to Christ’s verdict that his disciples quarrelled about which one of them would be the greatest (see Lk 9:48). 2 Helmold I, 14: “Testis est magister Adam, qui gesta Hammemburgensis ecclesiae pontificum disertissimo sermone conscripsit …” (“The witness is master Adam, who with great skill and fluency described the deeds of the bishops of the Church in Hamburg …”). -

A Possible Ring Fort from the Late Viking Period in Helsingborg

A POSSIBLE RING FORT FROM THE LATE VIKING PERIOD IN HELSINGBORG Margareta This paper is based on the author's earlier archaeologi- cal excavations at St Clemens Church in Helsingborg en-Hallerdt Weidhag as well as an investigation in rg87 immediately to the north of the church. On this occasion part of a ditch from a supposed medieval ring fort, estimated to be about a7o m in diameter, was unexpectedly found. This discovery once again raised the question as to whether an early ring fort had existed here, as suggested by the place name. The probability of such is strengthened by the newly discovered ring forts in south-western Scania: Borgeby and Trelleborg. In terms of time these have been ranked with four circular fortresses in Denmark found much earlier, the dendrochronological dating of which is y8o/g8r. The discoveries of the Scanian ring forts have thrown new light on south Scandinavian history during the period AD yLgo —zogo. This paper can thus be regarded as a contribution to the debate. Key words: Viking Age, Trelleborg-type fortress, ri»g forts, Helsingborg, Scania, Denmark INTRODUCTION Helsingborg's location on the strait of Öresund (the Sound) and its special topography have undoubtedly been of decisive importance for the establishment of the town and its further development. Opinions as to the meaning of the place name have long been divided, but now the military aspect of the last element of the name has gained the up- per. hand. Nothing in the find material indicates that the town owed its growth to crafts, market or trade activity. -

Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in Der Vormoderne Das Mittelalter Perspektiven Mediävistischer Forschung

Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 3 Wolfram Drews, Christian Scholl (Hrsg.) Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne ISBN 978-3-11-044483-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-044548-0 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-044550-3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2016 Walter De Gruyter GmbH Berlin/Boston Datenkonvertierung/Satz: Satzstudio Borngräber, Dessau-Roßlau Druck und Bindung: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ♾ Gedruckt auf säurefreiem Papier Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Inhaltsverzeichnis Wolfram Drews / Christian Scholl (Münster) Transkulturelle Verflechtungsprozesse in der Vormoderne. Zur Einleitung — VII Transkulturelle Wahrnehmungsprozesse und Diskurse Roland Scheel (Göttingen) Byzanz und Nordeuropa zwischen Kontakt, Verflechtung und Rezeption — 3 Lutz Rickelt (Münster) Zum Franken geworden. Zum Franken gemacht? Der Vorwurf der ‚Frankophilie‘ im spätbyzantinischen Binnendiskurs — 35 Kristin Skottki (Rostock) Kolonialismus avant la lettre? Zur umstrittenen Bedeutung der lateinischen Kreuzfahrerherrschaften in der Levante -

The Literary Tradition Erotic Insinuations, Irony, and Ekphrasis

Chapter 4: The Literary Tradition Erotic Insinuations, Irony, and Ekphrasis Even before the story of Pero and Cimon became a well-known subject matter in early modern art, European audiences were familiar with it through a millena- rian textual tradition and an oral tradition that left traces in Spain, Italy, Greece, Germany, Pomerania, Albania, and Serbia until the nineteenth century.1 The primary ancient source was Valerius Maximus’s Memorable Doings and Sayings (ca. 31 ce), of which at least fi fty-one diff erent editions were printed in Italy, Germany, Spain, and France before 1500.2 In the Middle Ages, Maximus’s book ranked as the most frequently copied manuscript next to the Bible.3 In addi- tion, numerous retellings of Maximus’s example of fi lial piety found their way into medieval fi ction, moral treatises, sermon literature, and compilations of “women’s worthies.” The story about the breastfeeding daughter as an allegory of fi lial piety in both its maternal and paternal variety was thus widely known to both learned and illiterate audiences in medieval and early modern Europe. The fame of Valerius Maximus’s Memorable Doings and Sayings in medieval and early modern Europe stands in stark contrast to its neglect in the scho- larly world since the nineteenth century. Only recently have literary historians rediscovered and translated his text, commenting on how the derivative nature of Maximus’s anecdotes relegated them to near total obscurity in the modern academic world.4 His compilation of historical and moral exempla acquired best-seller status already in antiquity because of the brief and succinct form in which he presented those memorable stories about the past, which he collected from a wide array of Latin and Greek authors, as well as their somewhat sensati- onalist content. -

Ystad Sweden Jazz Festival 2018!

VÄLKOMMEN TILL/WELCOME TO YSTAD SWEDEN JAZZ FESTIVAL 2018! Kära jazzvänner! Dear friends, Vi känner stor glädje över att för nionde gången kunna presentera It is with great pleasure that we present, for the ninth time, en jazzfestival med många spännande och intressanta konserter. a jazz festival with many exciting and interesting concerts – a mix Megastjärnor och legendarer samsas med unga blivande stjärnor. of megastars, legends and young stars of tomorrow. As in 2017, we Liksom 2017 använder vi Ystad Arena för konserter vilket möjliggör will use Ystad Arena as a venue to enable more people to experience för fler att uppleva musiken. I år erbjuder vi 44 konserter med drygt the concerts. This year we will present over 40 concerts featuring 200 artister och musiker. Tillsammans med Ystads kommun fortsätter more than 200 artists and musicians. In cooperation with Ystad vi den viktiga satsningen på jazz för barn, JazzKidz. Barnkonserterna Municipality, we are continuing the important music initiative for ges på Ystads stadsbibliotek. Tre konserter ges på Solhällan i Löderup. children, JazzKidz. The concerts for children will be held at Ystad Bered er på en magisk upplevelse den 5 augusti, då vi erbjuder en unik Library. There will be three concerts at Solhällan in Löderup. And, konsert vid Ales stenar, på Kåseberga, i soluppgången. get ready for a magical experience on 5 August, when we will Jazzfestivalen arrangeras sedan 2011 av den ideella föreningen present a unique sunrise concert at Ales stenar, near Kåseberga. Ystad Sweden Jazz och Musik i Syd i ett viktigt och förtroendefullt The jazz festival has been arranged since 2011 by the non-profit samarbete. -

Magnes: Der Magnetstein Und Der Magnetismus in Den Wissenschaften Der Frühen Neuzeit Mittellateinische Studien Und Texte

Magnes: Der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit Mittellateinische Studien und Texte Editor Thomas Haye (Zentrum für Mittelalter- und Frühneuzeitforschung, Universität Göttingen) Founding Editor Paul Gerhard Schmidt (†) (Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg) volume 53 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mits Magnes Der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit von Christoph Sander LEIDEN | BOSTON Zugl.: Berlin, Technische Universität, Diss., 2019 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sander, Christoph, author. Title: Magnes : der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit / von Christoph Sander. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Mittellateinische studien und texte, 0076-9754 ; volume 53 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019053092 (print) | LCCN 2019053093 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004419261 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004419414 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Magnetism–History–16th century. | Magnetism–History–17th century. Classification: LCC QC751 .S26 2020 (print) | LCC QC751 (ebook) | DDC 538.409/031–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053092 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053093 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 0076-9754 ISBN 978-90-04-41926-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-41941-4 (e-book) Copyright 2020 by Christoph Sander. Published by Koninklijke -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

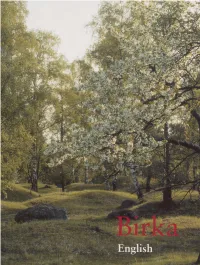

Digitalisering av redan tidigare utgivna vetenskapliga publikationer Dessa fotografier är offentliggjorda vilket innebär att vi använder oss av en undantagsregel i 23 och 49 a §§ lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk (URL). Undantaget innebär att offentliggjorda fotografier får återges digitalt i anslutning till texten i en vetenskaplig framställning som inte framställs i förvärvssyfte. Undantaget gäller fotografier med både kända och okända upphovsmän. Bilderna märks med ©. Det är upp till var och en att beakta eventuella upphovsrätter. SWEDISH NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD RIKSANTIKVARIEÄMBETET Mwtwl ^ bfikj O Opw UmA mwfrtMs O Cme-fou ö {wert* RoA«l O "liWIøf'El'i'fcA Birka Bente Magnus National Heritage Board View from the Fort Hill towards the Black Earth and Hemlanden (“The Homelands ”) at Birka. Birka is no. 2 in the series “Cultural Monuments in Sweden”, a set of guides to some of the most interesting ancient and historic monuments in Sweden. Author: Bente Magnus wrote the original text in Norwegian Translator: Alan Crozier Editor: Gunnel Friberg Layout: Agneta Modig ©1998 National Heritage Board ISBN 91-7209-125-8 1:3 Publisher: National Heritage Board, Box 5405, SE-114 84 Stockholm, Sweden Tel +46 (0)8 5191 8000 Printed by: Halls Offset, Växjö, 2004 Aerial view of Birka, 1997. The history of a town In Lake Mälaren, about 30 kilometres west protectedlocation, it attracted people from of Stockholm, between the fjords of Södra far and near to come to offer their goods Björkfjärdenand Hovgårdsfjärden,lies the and services. Today Birka is one of Swe island of Björkö. Until 1,100 years ago, den’s sites on Unesco’s World Heritage List there was a small, busy market town on and a popular attraction for thousands of the western shore of the island. -

The Hostages of the Northmen and the Place Names Can Indicate Traditions That Are Not Related to Hostages

Part V: Place Names Place names can provide information about hostages that can- not be obtained from other sources. In his study of sacred place names in the provinces around Lake Mälaren in present Sweden, Vikstrand points out that these names reflect ‘a social representa- tiveness’ that have grown out of everyday language.1 As a source, they can therefore represent social groups other than those found in the skaldic poetry which were directed to rulers in the milieu of the hird, and thus primarily give knowledge of performances of the elite. There are difficulties with analysis of place names, because sev- eral aspects of them must be considered. Place names are names of places, but Vikstrand points out that in the term ‘place’ you can distinguish three components: a geographical locality, a name, and a content that gives meaning to it.2 The relationship between these components is complicated and it is not always the given geographical location is the right one. For example, local people can ascribe place names an importance that they did not had dur- ing the time the researcher investigates. In this part, the point of departure will be a few place names from mainly eastern Scandinavia and neighboring areas. These are examples of historical provinces in present Sweden, Finland, and Estonia that can provide information about hostages; a com- parison is made with an example from Ireland. In western Scandinavia, corresponding place names with ‘hos- tage’ as component do not appear. There are some problems with these place names: they may be mentioned in just one source, the place names are not contemporary, the etymology can be ambiguous, How to cite this book chapter: Olsson, S. -

The Conversion of Scandinavia James E

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 1978 The ah mmer and the cross : the conversion of Scandinavia James E. Cumbie Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Cumbie, James E., "The ah mmer and the cross : the conversion of Scandinavia" (1978). Honors Theses. Paper 443. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES 11111 !ill iii ii! 1111! !! !I!!! I Ill I!II I II 111111 Iii !Iii ii JIJ JIJlllJI 3 3082 01028 5178 .;a:-'.les S. Ci;.r:;'bie ......:~l· "'+ori·.:::> u - '-' _.I".l92'" ..... :.cir. Rillin_: Dr. ~'rle Dr. :._;fic:crhill .~. pril lJ, 197f' - AUTHOR'S NOTE The transliteration of proper names from Old Horse into English appears to be a rather haphazard affair; th€ ~odern writer can suit his fancy 'Si th an~r number of spellings. I have spelled narr.es in ':1ha tever way struck me as appropriate, striving only for inte:::-nal consistency. I. ____ ------ -- The advent of a new religious faith is always a valuable I historical tool. Shifts in religion uncover interesting as- pects of the societies involved. This is particularly true when an indigenous, national faith is supplanted by an alien one externally introduced. Such is the case in medieval Scandinavia, when Norse paganism was ousted by Latin Christ- ianity. -

The Hostages of the Northmen: from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages

Part IV: Legal Rights It has previously been mentioned how hostages as rituals during peace processes – which in the sources may be described with an ambivalence, or ambiguity – and how people could be used as social capital in different conflicts. It is therefore important to understand how the persons who became hostages were vauled and how their new collective – the new household – responded to its new members and what was crucial for his or her status and participation in the new setting. All this may be related to the legal rights and special privileges, such as the right to wear coat of arms, weapons, or other status symbols. Personal rights could be regu- lated by agreements: oral, written, or even implied. Rights could also be related to the nature of the agreement itself, what kind of peace process the hostage occurred in and the type of hostage. But being a hostage also meant that a person was subjected to restric- tions on freedom and mobility. What did such situations meant for the hostage-taking party? What were their privileges and obli- gations? To answer these questions, a point of departure will be Kosto’s definition of hostages in continental and Mediterranean cultures around during the period 400–1400, when hostages were a form of security for the behaviour of other people. Hostages and law The hostage had its special role in legal contexts that could be related to the discussion in the introduction of the relationship between religion and law. The views on this subject are divided How to cite this book chapter: Olsson, S. -

Creating Holy People and Places on the Periphery

Creating Holy People and People Places Holy on theCreating Periphery Creating Holy People and Places on the Periphery A Study of the Emergence of Cults of Native Saints in the Ecclesiastical Provinces of Lund and Uppsala from the Eleventh to the Thirteenth Centuries During the medieval period, the introduction of a new belief system brought profound societal change to Scandinavia. One of the elements of this new religion was the cult of saints. This thesis examines the emergence of new cults of saints native to the region that became the ecclesiastical provinces of Lund and Uppsala in the twelfth century. The study examines theearliest, extant evidence for these cults, in particular that found in liturgical fragments. By analyzing and then comparing the relationship that each native saint’s cult had to the Christianization, the study reveals a mutually beneficial bond between these cults and a newly emerging Christian society. Sara E. EllisSara Nilsson Sara E. Ellis Nilsson Dissertation from the Department of Historical Studies ISBN 978-91-628-9274-6 Creating Holy People and Places on the Periphery Dissertation from the Department of Historical Studies Creating Holy People and Places on the Periphery A Study of the Emergence of Cults of Native Saints in the Ecclesiastical Provinces of Lund and Uppsala from the Eleventh to the Th irteenth Centuries Sara E. Ellis Nilsson med en svensk sammanfattning Avhandling för fi losofi e doktorsexamen i historia Göteborgs universitet, den 20 februari 2015 Institutionen för historiska studier (Department of Historical Studies) ISBN: 978-91-628-9274-6 ISBN: 978-91-628-9275-3 (e-publikation) Distribution: Sara Ellis Nilsson, [email protected] © Sara E. -

Aristocratic Society in Abruzzo, C.950-1140

Aristocratic society in Abruzzo, c.950-1140 Felim McGrath A dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Dublin 2014 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. ____________________________ Felim McGrath iii Summary This thesis is an examination of aristocratic society in the Italian province of Abruzzo from the mid-tenth century to the incorporation of the region into the kingdom of Sicily in 1140. To rectify the historiographical deficit that exists concerning this topic, this thesis analyses the aristocracy of Abruzzo from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. It elucidates the political fragmentation apparent in the region before the Norman invasion, the establishment and administration of the Abruzzese Norman lordships and their network of political connections and the divergent political strategies employed by the local aristocracy in response to the Norman conquest. As the traditional narrative sources for the history of medieval southern Italy provide little information concerning Abruzzo, critical analysis of the idiosyncratic Abruzzese narrative and documentary sources is fundamental to the understanding this subject and this thesis provides a detailed examination of the intent, ideological context and utility of these sources to facilitate this investigation. Chapter 1 of this thesis examines the historical and ideological context of the most important medieval Abruzzese source – the chronicle-cartulary of San Clemente a Casauria.