A Historical Perspective on Formula 1 Motor Racing 1950 - 2006*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I MIEI 40 ANNI Di Progettazione Alla Fiat I Miei 40 Anni Di Progettazione Alla Fiat DANTE GIACOSA

DANTE GIACOSA I MIEI 40 ANNI di progettazione alla Fiat I miei 40 anni di progettazione alla Fiat DANTE GIACOSA I MIEI 40 ANNI di progettazione alla Fiat Editing e apparati a cura di: Angelo Tito Anselmi Progettazione grafica e impaginazione: Fregi e Majuscole, Torino Due precedenti edizioni di questo volume, I miei 40 anni di progettazione alla Fiat e Progetti alla Fiat prima del computer, sono state pubblicate da Automobilia rispettivamente nel 1979 e nel 1988. Per volere della signora Mariella Zanon di Valgiurata, figlia di Dante Giacosa, questa pubblicazione ricalca fedelmente la prima edizione del 1979, anche per quanto riguarda le biografie dei protagonisti di questa storia (in cui l’unico aggiornamento è quello fornito tra parentesi quadre con la data della scomparsa laddove avve- nuta dopo il 1979). © Mariella Giacosa Zanon di Valgiurata, 1979 Ristampato nell’anno 2014 a cura di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. Logo di prima copertina: courtesy di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. … ”Noi siamo ciò di cui ci inebriamo” dice Jerry Rubin in Do it! “In ogni caso nulla ci fa più felici che parlare di noi stessi, in bene o in male. La nostra esperienza, la nostra memoria è divenuta fonte di estasi. Ed eccomi qua, io pure” Saul Bellow, Gerusalemme andata e ritorno Desidero esprimere la mia gratitudine alle persone che mi hanno incoraggiato a scrivere questo libro della mia vita di lavoro e a quelle che con il loro aiuto ne hanno reso possibile la pubblicazione. Per la sua previdente iniziativa di prender nota di incontri e fatti significativi e conservare documenti, Wanda Vigliano Mundula che mi fu vicina come segretaria dal 1946 al 1975. -

2013 Formula One Grand Prix

1 Cover Sheet Event: 2013 Austin Formula One Grand Prix (F1 USGP) Date: November 15 – 17, 2013; Location: Austin, Texas Report Date: September 15, 2014 2 Post Event Analysis 2013 Austin Formula One Grand Prix (F1 USGP) I. Summary of Conclusion This office concludes that the initial estimate of direct, indirect, and induced tax impact of $25,024,710 is reasonable based on the tax increases that occurred in the market area during the period in which the 2012 Austin Formula One Grand Prix (F1 USGP) event occurred. II. Introduction This post-event analysis of the F1 USGP is intended to evaluate the short-term tax benefits to the state through review of tax revenue data to determine the level of incremental tax impact from the event. A primary purpose of this analysis is to determine the reasonableness of the initial incremental tax estimate made by the Comptroller’s office prior to the event, in support of a request for a Major Events Trust Fund (METF). The initial estimate is included in Appendix A. Long term tax benefits due to the construction and ongoing operations of the venue are not considered in this analysis, but are significant1. Large events, particularly “premier events” such as this one, with heavy promotion, corporate sponsorship and spending, and “luxury” spending by visitors, will tend to create significant ripples in the local economy, and in fact, even the regional economy outside the immediate area considered in this report. The purpose of this report is to analyze the changes in tax collections during the period in which the event occurred. -

Formula One™ British Grand Prix

Formula One™ British Grand Prix EXPERIENCE THE POWER AND GLAMOUR OF FORMULA ONE™ ON FIVE CONTINENTS The British Grand Prix at Silverstone is the oldest race on the DATE From 11th - 14th July 2019 Formula One™ calendar, having been a feature since the very LOCATION Silverstone Circuit, England beginning of the World Championship in 1958. PRICE Click on the different options While the circuit has been reconfigured many times over the Please call for more details and to register your years, it retains its fast-flowing character and remains a interest in experiencing this unique event. formidable challenge for drivers. Each year, hoards of knowledgeable and enthusiastic fans turn out to create an intoxicating atmosphere that makes the British Grand Prix an unmissable sporting fixture. •Formula One Paddock ClubTM• Watch the drama unfold from a privileged viewing position above the Pit Lane, with one of the highest levels of hospitality at a Grand Prix. •Hospitality Experiences• Enjoy F1TM from the best vantage points with Silverstone hospitality. •Grandstand (tickets only)• Soak up the incredible atmosphere with our three-day grandstand and circuit access. Click on each to see the different options. Terms and Conditions *Formula One Paddock Club™ tickets tickets supplied to you by BAM Please get in touch for more details and to register your interest in Motorsports Ltd. The F1 logo, F1 FORMULA 1 logo, F1, FORMULA 1, FIA experiencing this unique event. FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP, GRAND PRIX, FORMULA 1 PADDOCK CLUB, PADDOCK CLUB, F1 PADDOCK CLUB and related marks are trademarks of Formula One Licensing BV, a Formula 1 *Formula One tickets supplied to you by BAM Motorsports Ltd, an official distributor. -

SCCA Fastrack News January 2020 Page 1 CLUB RACING BOARD

Club Racing Board CLUB RACING BOARD MINUTES | December 3, 2019 The Club Racing Board met by teleconference on November 5, 2019. Participating were Peter Keane, Chairman; David Arken, Tony Ave, Jim Goughary, Paula Hawthorne, Sam Henry, John LaRue, Steve Strickland and Shelly Pritchett, secretary. Also participating were: Bob Dowie, Marcus Merideth, and Peter Jankovskis BoD liaisons; Eric Prill, Chief Operations Officer, Deanna Flanagan, Director of Road Racing; Rick Harris, Club Racing Technical Manager and Scott Schmidt, Technical Services Assistant. The following decisions were made: Member Advisory None. No Action Required F 1. #27905 (James Rogerson) F4 into FX Thank you for your letter. The Club Racing Board appreciates your comments. FA 1. #27516 (JEREMY HILL) Request to Balance FA and FB Thank you for your letter. Please see the response to letter #27319 in this Fastrack's Technical Bulletin. 2. #27544 (DAVID OLEARY) Concerns About Grouping With FA Thank you for your letter. Please see the response to letter #27319 in this Fastrack's Technical Bulletin. 3. #27785 (Greg Pizzo) Allow Mods to Current FB Rules So That F1000/FB Is Competitive Thank you for your letter. Please see the response to letter #27319 in this Fastrack's Technical Bulletin. 4. #27789 (Dave Caswell) FB/FA Integration for 2020 Thank you for your letter. Please see the response to letter #27319 in this Fastrack's Technical Bulletin. 5. #27792 (S. Jay Novak) Request for Engines for FB Cars Integrated Into FA Thank you for your letter. Please see the response to letter #27319 in this Fastrack's Technical Bulletin. 6. -

Books for Sale Title Author Price $ a History of the Rob Roy Hill

Books for Sale Title Author Price $ A History of the Rob Roy Hill Climb Leon Sims 45 Australian Cars & motoring John Goode 10 Boxer [ Ferrari } Jonathon Thompson 40 Cars of the 30s & 40s Michael Sedgewick 40 Cars Cars Cars Cars Sydney Charles Haughton Davis 10 Cooper Cars Doug Nye 60 Driving Ambition Alan Jones , Keith Botsford 15 Ferrari Godfrey Eaton 20 Ferrari [Great Marques ] Godfrey Eaton 10 From Redex to Repco Bill Tuckey , T.B. Floyd 40 Gardner a dream come true Nick Hartgerink 15 Grand Prix 1985 F1 World Championship Nigel Roebuck 25 Porsche Grand Marques Chris Harvey 10 Holden vs Ford the cars ,culture & competition Steve Bedwell 20 Lex Davison – Larger than life Graham Howard 50 Murray Walker Unless I ‘m very much mistaken Murray Walker 10 Raceyear 1984 Gary Sparke 15 Raceyear 1985 Gary Sparke 15 Racing Cars Racing Cars Richard Hough 15 The exciting world of Jackie Stewart Jackie Stewart 12 The Great Cars Ralph Stein 18 The Great Racing Cars & Drivers Charles Fox 15 The History of Motor Racing William Body , Brian Laban 10 The Power & the Glory A century of Motor Racing Ivan Rendall 10 The Racing Car Cecil Clutton , Cyrin Posthumus , Denis Jenkinson 15 The Vintage Motor Car C Clutton , J Stanford 10 Champion Year Mike Hawthorn 25 All Colour Book of Racing Cars Brad King 10 Racing Cars & the history of Motor Sport Peter Roberts 20 Porsche Michael Colton 20 Ferrari – The Grand Prix Cars Alan Henry 20 The Crown of the Road Susan Priestly 5 Motor Racing The Australian Way Brian Hanrahan 30 Allan Moffat Scrapbook Brian Hanrahan 15 Motor Racing Today Innes Ireland 15 The Jack Brabham Story Jack Brabham 35 Riley – the production & competition History pre 1939 A T Birmingham 45 Vanwall – the story of Tony Vanwall Denis Jenkinson 45 & his racing cars. -

Hitlers GP in England.Pdf

HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND Donington 1937 and 1938 Christopher Hilton FOREWORD BY TOM WHEATCROFT Haynes Publishing Contents Introduction and acknowledgements 6 Foreword by Tom Wheatcroft 9 1. From a distance 11 2. Friends - and enemies 30 3. The master’s last win 36 4. Life - and death 72 5. Each dangerous day 90 6. Crisis 121 7. High noon 137 8. The day before yesterday 166 Notes 175 Images 191 Introduction and acknowledgements POLITICS AND SPORT are by definition incompatible, and they're combustible when mixed. The 1930s proved that: the Winter Olympics in Germany in 1936, when the President of the International Olympic Committee threatened to cancel the Games unless the anti-semitic posters were all taken down now, whatever Adolf Hitler decrees; the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin and Hitler's look of utter disgust when Jesse Owens, a negro, won the 100 metres; the World Heavyweight title fight in 1938 between Joe Louis, a negro, and Germany's Max Schmeling which carried racial undertones and overtones. The fight lasted 2 minutes 4 seconds, and in that time Louis knocked Schmeling down four times. They say that some of Schmeling's teeth were found embedded in Louis's glove... Motor racing, a dangerous but genteel activity in the 1920s and early 1930s, was touched by this, too, and touched hard. The combustible mixture produced two Grand Prix races at Donington Park, in 1937 and 1938, which were just as dramatic, just as sinister and just as full of foreboding. This is the full story of those races. -

REV Entry List

Entry List Goodwood Revival 2019 Race(s): 1 Kinrara Trophy presented by Hackett - For closed-cockpit GT cars, of three litres and over, of a type that raced before 1963 Race Status: National A Car Shelter Year Make and Model Entrant Confirmed Driver(s) No. No. 1 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Macari, Joe Kristensen, Tom/Macari, Joe 2 1962 Ferrari 250 GT SWB Evans, Chris/Livingstone, Ian Cottingham, James/TBC, 3 1962 AC Cobra Lovett, Paul Bryant, Oliver/Sergison, Ewen 4 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Racing Team Holland Franchitti, Dario/Hugenholtz, John 5 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Alexander, Tom Alexander, Tom/Le Blanc, Karsten 6 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Friedrichs, Wolfgang Hadfield, Simon/Turner, Darren 7 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Gaye, Vincent Gaye, Vincent/Twyman, Joe 8 1963 Austin-Healey 3000 Steinke, Thomas Draper, Julien/Steinke, Thomas 9 1961 Jaguar E-type Coombs Automotive Graham, Stuart/March, Charlie 10 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Müller, Urs Müller, Arlette/Müller, Urs 11 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Devis, Marc Devis, Marc/O'Connell, Martin 12 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO FICA FRIO Ltd Monteverde, Carlos/Pearson, Gary 14 1961 Jaguar E-type FHC Meins, Richard Bentley, Andrew/Meins, Richard 15 1961 Jaguar E-type Lindemann, Adam Lindemann, Adam/Meaden, Richard 16 1961 Jaguar E-type FHC Midgley, Mark Lockie, Calum/Midgley, Mark 17 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Hayden, Andrew Hayden, Andrew/Hibberd, Andrew 18 1964 Jaguar E-type FHC Hart, David Hart, David/Hart, Olivier 20 1962 Ferrari 250 GT SWB Dumolin, Christian Dumolin, Christian/Thibaut, Pierre-Alain 21 1960 -

Formula 1 Race Car Performance Improvement by Optimization of the Aerodynamic Relationship Between the Front and Rear Wings

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Engineering FORMULA 1 RACE CAR PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT BY OPTIMIZATION OF THE AERODYNAMIC RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE FRONT AND REAR WINGS A Thesis in Aerospace Engineering by Unmukt Rajeev Bhatnagar © 2014 Unmukt Rajeev Bhatnagar Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science December 2014 The thesis of Unmukt R. Bhatnagar was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark D. Maughmer Professor of Aerospace Engineering Thesis Adviser Sven Schmitz Assistant Professor of Aerospace Engineering George A. Lesieutre Professor of Aerospace Engineering Head of the Department of Aerospace Engineering *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract The sport of Formula 1 (F1) has been a proving ground for race fanatics and engineers for more than half a century. With every driver wanting to go faster and beat the previous best time, research and innovation in engineering of the car is really essential. Although higher speeds are the main criterion for determining the Formula 1 car’s aerodynamic setup, post the San Marino Grand Prix of 1994, the engineering research and development has also targeted for driver’s safety. The governing body of Formula 1, i.e. Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) has made significant rule changes since this time, primarily targeting car safety and speed. Aerodynamic performance of a F1 car is currently one of the vital aspects of performance gain, as marginal gains are obtained due to engine and mechanical changes to the car. Thus, it has become the key to success in this sport, resulting in teams spending millions of dollars on research and development in this sector each year. -

10 Years of BMW F1 Engines Abstract

- 1 - Prof. Dr.-Ing. Mario Theissen, Dipl.-Ing. Markus Duesmann, Dipl.-Ing. Jan Hartmann, Dipl.-Ing. Matthias Klietz, Dipl.-Ing. Ulrich Schulz BMW Group, Munich 10 Years of BMW F1 Engines Abstract BMW engines gave the company a presence in Formula One from 2000 to 2009. The overall project can be broken down into a preparatory phase, its years as an engine supplier to the Williams team, and a period competing under the banner of its own BMW Sauber F1 Team. The conception, design and deployment of the engines were defined by the Formula One regulations, which were subject to change virtually every year. Reducing costs was the principal aim of these revisions. Development expenditure was scaled down gradually as a result of the technical restrictions imposed on the teams and finally through homologation and a freeze on development. Engine build costs were limited by the increased mileage required of each engine and the restrictions on testing. A lower number of engines were therefore required for each season. A second aim, reduced engine output, was achieved with the switch from 3.0-litre V10 engines to 2.4-litre V8s for the 2006 season. In the early years of its involvement in F1, BMW developed and built a new engine for each season amid a high-pressure competitive environment. This process saw rapid improvements made in engine output and weight, and the BMW powerplant soon attained benchmark status in F1. In recent years, development work focused on raising mileage capability and reliability without changing the engine concept itself. The P86/9 of the 2009 season achieved the same engine output, despite a 20% reduction in displacement, of the E41/4 introduced at the beginning of the 2000 season. -

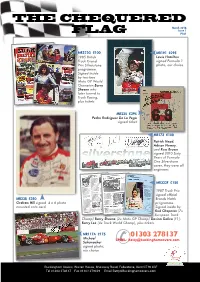

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

Purpose Driven Initiative / 2

A report on the Contribution of Motorsport to Health, Safety & the Environment Commissioned by the Created by #PurposeDriven A PURPOSE DRIVEN INITIATIVE / 2 FOREWORD 03 SUPERIOR ELECTRIC 43 INTRODUCTION 04 15. Leading The Charge 44 16. Beyond The Battery 46 METHODOLOGY 07 17. Going The Extra Mile 48 BETTER HEALTHCARE 09 18. The Lightning Laboratory 50 01. Racing Against The Pandemic 10 HYPER EFFICIENCY 52 02. Collaboration In A Crisis 12 19. Back To The Future 53 03. Keeping Fingers On The Pulse 14 20. Electrifying Progress 55 04. Transplanting Technology 16 21. Shifting The Paradigm 57 05. The World’s Safest Crib 18 22. Going Against The Flow 59 06. Operation Pit Stop 20 23. Transforming Tyres 61 GREENER LIVING 22 ALONG THE ROAD 63 07. Putting Waste On Ice 23 24. Additive Acceleration 64 08. The Great Data Race 25 25. Fueling Forward Thinking 66 09. Reinventing Two Wheels 27 26. The Ultimate Showcase 68 10. Flying In The Drivers Seat 29 11. Aerodynamic Architecture 31 CONCLUSION 70 SAFER MOTORISTS 33 INDEX / SOURCES 77 12. Setting The Standard 34 13. A Model For Safety 37 14. A Foundation For Society 40 A PURPOSE DRIVEN INITIATIVE FORWARD / 3 Foreword by President Jean Todt Ladies, Gentlemen, Motorsport has always participated in the progress of society, particularly in terms of technology and innovation to improve health and safety as well as to protect our environment. Advances on the racetrack find their way to the road, helping to preserve lives and the planet. This has probably never been as clear as in the response of the community to the global pandemic this year. -

The Last Road Race

The Last Road Race ‘A very human story - and a good yarn too - that comes to life with interviews with the surviving drivers’ Observer X RICHARD W ILLIAMS Richard Williams is the chief sports writer for the Guardian and the bestselling author of The Death o f Ayrton Senna and Enzo Ferrari: A Life. By Richard Williams The Last Road Race The Death of Ayrton Senna Racers Enzo Ferrari: A Life The View from the High Board THE LAST ROAD RACE THE 1957 PESCARA GRAND PRIX Richard Williams Photographs by Bernard Cahier A PHOENIX PAPERBACK First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson This paperback edition published in 2005 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd, Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin's Lane, London WC2H 9EA 10 987654321 Copyright © 2004 Richard Williams The right of Richard Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 75381 851 5 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives, pic www.orionbooks.co.uk Contents 1 Arriving 1 2 History 11 3 Moss 24 4 The Road 36 5 Brooks 44 6 Red 58 7 Green 75 8 Salvadori 88 9 Practice 100 10 The Race 107 11 Home 121 12 Then 131 The Entry 137 The Starting Grid 138 The Results 139 Published Sources 140 Acknowledgements 142 Index 143 'I thought it was fantastic.