Area by Area the Machine Unfolds”: the Improvisational Performance Practice of the Art Ensemble of Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underserved Communities

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2016 Spring Grant Announcement Artistic Discipline/Field Listings Project details are accurate as of April 26, 2016. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Click the grant area or artistic field below to jump to that area of the document. 1. Art Works grants Arts Education Dance Design Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts 2. State & Regional Partnership Agreements 3. Research: Art Works 4. Our Town 5. Other Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Information is current as of April 26, 2016. Arts Education Number of Grants: 115 Total Dollar Amount: $3,585,000 826 Boston, Inc. (aka 826 Boston) $10,000 Roxbury, MA To support Young Authors Book Program, an in-school literary arts program. High school students from underserved communities will receive one-on-one instruction from trained writers who will help them write, edit, and polish their work, which will be published in a professionally designed book and provided free to students. Visiting authors, illustrators, and graphic designers will support the student writers and book design and 826 Boston staff will collaborate with teachers to develop a standards-based curriculum that meets students' needs. Abada-Capoeira San Francisco $10,000 San Francisco, CA To support a capoeira residency and performance program for students in San Francisco area schools. Students will learn capoeira, a traditional Afro-Brazilian art form that combines ritual, self-defense, acrobatics, and music in a rhythmic dialogue of the body, mind, and spirit. -

Art Ensemble of Chicago Thelonious Sphere Monk

Art ensemble of chicago thelonious sphere monk Find a Art Ensemble Of Chicago* With Cecil Taylor - Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming Of The Masters Vol.2 first pressing or reissue. Complete your Art. Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters Series Vol. 2 is an album by the Art Ensemble of Chicago and Cecil Taylor released on the Japanese DIW. Art Ensemble of Chicago, Cecil Taylor - Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters, Vol.2 - Music. This CD promises much more than it delivers, appearing to be a tribute to Thelonious Monk that features the Art Ensemble of Chicago and guest pianist Cecil. Find album release information for Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters, Vol. 2 - The Art Ensemble of Chicago on AllMusic. Thelonious Sphere Monk - Dreaming of the Masters Vol. 2 Recorded in , at Systems Two Studios, Brooklyn. Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters, Vol. 2, an Album by Art Ensemble of Chicago With Cecil Taylor. Released in on (catalog no. CK Albuminformatie voor Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the masters ; vol.2 van Art Ensemble of Chicago. ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO WITH CECIL TAYLOR ~ Thelonious Sphere Monk - Dreaming Of The Masters Vol. 2 []. C'est comme un. Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the Masters, Vol. 2 by The Art Ensemble of Chicago release on May 06, Thelonious Sphere Monk: Dreaming of the. "Dreaming of the Masters"、"Intro to Fifteen"、"Excerpt from Fifteen, Pt. 3A" とその他を含む、アルバム「Thelonious Sphere Monk」の曲を聴こう。 . Acquista il CD album Thelonious Sphere Monk di Art Ensemble Of Chicago in offerta; album e dischi in vendita online a prezzi scontati su La Feltrinelli. -

Joseph Jarman's Black Case Volume I & II: Return

Joseph Jarman’s Black Case Volume I & II: Return From Exile February 13, 2020 By Cam Scott When composer, priest, poet, and instrumentalist Joseph Jarman passed away in January 2019, a bell sounded in the hearts of thousands of listeners. As an early member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), as well as its flagship group, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Jarman was a key figure in the articulation of Great Black Music as a multi- generational ethic rather than a standard repertoire. As an ordained Buddhist priest, Jarman’s solicitude transcended philosophical affinity and deepened throughout his life as his music evolved. His musical, poetic, and religious paths appear to have been mutually informative, in spite of a hiatus from public performance in the nineties—and to encounter Jarman’s own words is to understand as much. The full breadth of this complexity is celebrated in the long-awaited reissue of Black Case Volume I & II: Return from Exile, a blend of smut and sutra, poetry and polemic, that feels like a reaffirmation of Jarman’s ambitious vision in the present day. Black Case wears its context proudly. A near-facsimile of the original 1977 publication by the Art Ensemble of Chicago (which itself was built upon a coil-bound printing from 1974), the volume serves as a time capsule of a key period in the development of an emancipatory musical and cultural program, and an intimate portrait of the artist-as-revolutionary. Black Case, then, feels most contemporary where it is most of its time, as a document of Black militancy and programmatic self-determination in which—to paraphrase Larry Neal’s 1968 summary of the Black Arts Movement—ethics and aesthetics, individual and community, are tightly unified. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Museum Archivist

Newsletter of the Museum Archives Section Museum Archivist Summer 2020 Volume 30, Issue 2 Letter From the Chair Fellow MAS and SAA members, To be blunt, we are currently in the midst of a challenging period of historic proportions. On top of a charged atmosphere filled with vitriol, 2020 has witnessed the unfolding of both a global pandemic and racial tensions exacerbated by systemic racism in law enforcement. The combination of this perfect storm has sowed a climate of chaos and uncertainty. It is easy to feel demoralized and discouraged. For your own mental health, allow yourself to feel. Allow yourself to take a breath and acknowledge that you are bearing witness to a uniquely challenging period like few in global history. Yet, there is reason to hope. The trite phrase, “that which does not kill us only makes us stronger” has significance. We adapt, learn, grow and improve. If this all is to be viewed as an incredible challenge, rest assured, we will overcome it. (To use yet another timeless phrase, “this, too, shall pass.”) I am curious to see what new measures, what new policies, what new courses of action we, as professionals in the field(s) of libraries, archives, and museums (LAMs) will implement to further enhance and reinforce the primary goals of our respective professions. One question that keeps coming to mind is how the archives field—specifically as it relates to museums— will survive and adapt in the post-COVID-19 world. People will continue to turn to publicly available research material to learn and educate others. -

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

May-June 293-WEB

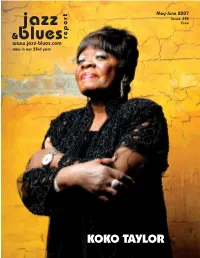

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Wavelength (April 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 4-1981 Wavelength (April 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (April 1981) 6 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL 1 981 VOLUME 1 NUMBE'J8. OLE MAN THE RIVER'S LAKE THEATRE APRIL New Orleans Mandeville, La. 6 7 8 9 10 11 T,HE THE THIRD PALACE SUCK'S DIMENSION SOUTH PAW SALOON ROCK N' ROLL Baton Rouge, La. Shreveport. La. New Orleans Lalaye"e, La. 13 14 15 16 17 18 THE OLE MAN SPECTRUM RIVER'S ThibOdaux, La. New Orleans 20 21 22 23 24 25 THE LAST CLUB THIRD HAMMOND PERFORMANCE SAINT DIMENSION SOCIAL CLUB OLE MAN CRt STOPHER'S Baton Rouge, La. Hammond, La. RIVER'S New Orleans New Orleans 27 29 30 1 2 WEST COAST TOUR BEGINS Barry Mendelson presents Features Whalls Success? __________________6 In Concert Jimmy Cliff ____________________., Kid Thomas 12 Deacon John 15 ~ Disc Wars 18 Fri. April 3 Jazz Fest Schedule ---------------~3 6 Pe~er, Paul Departments April "Mary 4 ....-~- ~ 2 Rock 5 Rhylhm & Blues ___________________ 7 Rare Records 8 ~~ 9 ~k~ 1 Las/ Page _ 8 Cover illustration by Rick Spain ......,, Polrick Berry. Edllor, Connie Atkinson. -

Tolono Library CD List

Tolono Library CD List CD# Title of CD Artist Category 1 MUCH AFRAID JARS OF CLAY CG CHRISTIAN/GOSPEL 2 FRESH HORSES GARTH BROOOKS CO COUNTRY 3 MI REFLEJO CHRISTINA AGUILERA PO POP 4 CONGRATULATIONS I'M SORRY GIN BLOSSOMS RO ROCK 5 PRIMARY COLORS SOUNDTRACK SO SOUNDTRACK 6 CHILDREN'S FAVORITES 3 DISNEY RECORDS CH CHILDREN 7 AUTOMATIC FOR THE PEOPLE R.E.M. AL ALTERNATIVE 8 LIVE AT THE ACROPOLIS YANNI IN INSTRUMENTAL 9 ROOTS AND WINGS JAMES BONAMY CO 10 NOTORIOUS CONFEDERATE RAILROAD CO 11 IV DIAMOND RIO CO 12 ALONE IN HIS PRESENCE CECE WINANS CG 13 BROWN SUGAR D'ANGELO RA RAP 14 WILD ANGELS MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 15 CMT PRESENTS MOST WANTED VOLUME 1 VARIOUS CO 16 LOUIS ARMSTRONG LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB JAZZ/BIG BAND 17 LOUIS ARMSTRONG & HIS HOT 5 & HOT 7 LOUIS ARMSTRONG JB 18 MARTINA MARTINA MCBRIDE CO 19 FREE AT LAST DC TALK CG 20 PLACIDO DOMINGO PLACIDO DOMINGO CL CLASSICAL 21 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS RO ROCK 22 STEADY ON POINT OF GRACE CG 23 NEON BALLROOM SILVERCHAIR RO 24 LOVE LESSONS TRACY BYRD CO 26 YOU GOTTA LOVE THAT NEAL MCCOY CO 27 SHELTER GARY CHAPMAN CG 28 HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN WORLEY, DARRYL CO 29 A THOUSAND MEMORIES RHETT AKINS CO 30 HUNTER JENNIFER WARNES PO 31 UPFRONT DAVID SANBORN IN 32 TWO ROOMS ELTON JOHN & BERNIE TAUPIN RO 33 SEAL SEAL PO 34 FULL MOON FEVER TOM PETTY RO 35 JARS OF CLAY JARS OF CLAY CG 36 FAIRWEATHER JOHNSON HOOTIE AND THE BLOWFISH RO 37 A DAY IN THE LIFE ERIC BENET PO 38 IN THE MOOD FOR X-MAS MULTIPLE MUSICIANS HO HOLIDAY 39 GRUMPIER OLD MEN SOUNDTRACK SO 40 TO THE FAITHFUL DEPARTED CRANBERRIES PO 41 OLIVER AND COMPANY SOUNDTRACK SO 42 DOWN ON THE UPSIDE SOUND GARDEN RO 43 SONGS FOR THE ARISTOCATS DISNEY RECORDS CH 44 WHATCHA LOOKIN 4 KIRK FRANKLIN & THE FAMILY CG 45 PURE ATTRACTION KATHY TROCCOLI CG 46 Tolono Library CD List 47 BOBBY BOBBY BROWN RO 48 UNFORGETTABLE NATALIE COLE PO 49 HOMEBASE D.J. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Träumend Von Den Großen Schwarzen Schwänen“ (*)

KULTUR UND GESELLSCHAFT Organisationseinheit : 46 Reihe : LITERATUR 0.05 Uhr Titel der Sendung: Träumend von den großen Üb schwarzen Schwänen – Die Ästhetik des Widerstands in Alejo Carpentiers Le Sacre du Printemps Autor : : Klaus Emrich Redaktion: : Sigried Wesener Sendetermin : 28.12.2014 Besetzung : Sprecher : Zitatorin : Zitator Regie : Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis: Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Jede Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in den §§ 45 bis 63 Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig © Deutschlandradio Deutschlandradio Kultur Funkhaus Berlin Hans-Rosenthal-Platz 10825 Berlin Telefon (030) 8503-0 1 Klaus Emrich „Träumend von den Großen Schwarzen Schwänen“ (*) Die Ästhetik des Widerstands in Alejo Carpentiers „Le Sacre du Printemps“ (*) Alejo Carpentier, Le Sacre du Printemps, Frankfurt/Main 1993, S.11 18. März 2o14 2 MUSIK: Steve Coleman & Dave Holland Phase Space (track 2): Dream of the Elders (nach ca 25’ übersprechen) ZITATOR: Menschen von heute, die schon danach trachteten, Menschen von morgen zu sein. (1:529) SPRECHER: Alejo Carpentier. Le Sacre du Printemps. La Consagración de la Primavera: Alejo Carpentier schrieb sein opus magnum 1978 als „Epos der kubanischen Revolution“. Er verbindet die Geschichte der russischen Tänzerin Vera und des cubanischen Architekten Enrique mit den historischen Ereignissen während des spanischen Krieges 1936 bis 1939 und dem bewaffneten