Traditional Storage and Utilization Practices on Root and Tuber Crops of Selected Indigenous People in the Northern Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tropang Maruya

Episode 1 & 2: Tropang Maruya “Kada Tropa” Session Guide Episode 1 at 2: “Tropang Maruya” I. Mga Layunin 1. Naipakikita ang kakayahan, katangian at paraan ng pag-iisip batay sa “brain preferences”. 2. Naiisa-isa ang mga salita na makatutulong sa pagiging matagumpay ng isang entrepreneur: • Pagkamalikhain • Lawak ng pananaw • Talino at kakayahan • Paninindigan • Pagmamahal sa gawain • Pagiging sensitibo sa damdamin ng iba • Katatagan at pagkamatiyaga 3. Natutuklasan ang sariling katangian 4. Nakikilala ang pagkakaiba ng ugali at paraan ng pag-iisip ng bawat isa. II. Paksa: “Tropang Maruya” Katangian, kakayahan at paraan ng pag-iisip batay sa brain preferences. “Tropang Maruya” video III. Pamamaraan Bago manood ng programa, itanong ang sumusunod: 1. Ano ang papasok sa isip kung marinig ang pamagat na “Tropang Maruya”? 2. Ano ang alam mo tungkol sa paksa? 3. Ano pa ang gusto mong malaman tungkol sa maruya? 4. Sa palagay mo bakit “Tropang Maruya” ang pamagat ngating panonoorin? 5. Maghuhulaan tayo ngayon. Isulat ninyo sa inyong papel kung ano ang gagawin ng tropa para magtagumpay. Sabihin: 6. Basahin ang isinulat ninyo. Tingnan natinkung ang hula ninyong mangyayari ang magaganap sa video na ating panonoorin. Pagkatapos mapanood ang programa A. Activity (Gawain) 1. Itanong: • Anu-ano ang tanim ninyo sa paligid ng bahay? • Paano ninyo pinakikinabangan ang bunga ng mga tanim? Kumikita ba kamo kayo? Paano kayo kumikita? • Hal. Mga prutas Saging. Ang saging ninyong tanim ay saba. Anu-ano ang inyong magagawa sa saging? 2. Magpapakita ang mobile teacher ng maruya. Ilarawan sa brown paper o sa pisara. Ipalagay natin na maruya ang nasa pisara. -

Lactic Acid Bacteria in Philippine Traditional Fermented Foods

Chapter 24 Lactic Acid Bacteria in Philippine Traditional Fermented Foods Charina Gracia B. Banaay, Marilen P. Balolong and Francisco B. Elegado Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/50582 1. Introduction The Philippine archipelago is home to a diverse array of ecosystems, organisms, peoples, and cultures. Filipino cuisine is no exception as distinct regional flavors stem from the unique food preparation techniques and culinary traditions of each region. Although Philippine indigenous foods are reminiscent of various foreign influences, local processes are adapted to indigenous ingredients and in accordance with local tastes. Pervasive throughout the numerous islands of the Philippines is the use of fermentation to enhance the organoleptic qualities as well as extend the shelf-life of food. Traditional or indigenous fermented foods are part and parcel of Filipino culture since these are intimately entwined with the life of local people. The three main island-groups of the Philippines, namely – Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao, each have their own fermented food products that cater to the local palate. Fermentation processes employed in the production of these indigenous fermented foods often rely entirely on natural microflora of the raw material and the surrounding environment; and procedures are handed down from one generation to the next as a village-art process. Because traditional food fermentation industries are commonly home-based and highly reliant on indigenous materials without the benefit of using commercial starter cultures, microbial assemblages are unique and highly variable per product and per region. Hence the possibility of discovering novel organisms, products, and interactions are likely. -

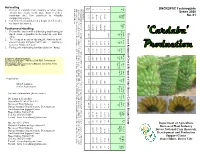

DNCRDPSC Technoguide Series 2020 No

No. 01 Series 2020 Support Support Center Bago Davao City Oshiro, Bureau of Plant Industry Industry Plant of Bureau DNCRDPSC Technoguide DNCRDPSC Department of Agriculture Department of Development and Production Davao National Crop Research, Research, Davao National Crop Five-year Estimated Cost & Return of a One-Hectare Cardaba Banana Farm YEA Harves- Gross Estab- Weed- Fertili- Irriga- Sucker Mat Bunch Managing Har- Total Yearly ROI Cumula- Cumula- Cumu- table Income Net (%) tive tive Net lative R Fruits (P) lishment ing zation tion Man- Sanita- Care Pest and vesting Cost per Income Produc- Income ROI (kg) Cost Cost Cost Cost agement tion (P) (P) Diseases (P) hectare (P) tion Cost (P) (%) (P) (P) (P) (P) Cost (P) (P) (P) (P) 1 - - 34,635 2,300 11,950 2,000 800 1,350 - 1,300 - 54,335 -54,335 -100 54,335 -54,335 -100 2 15,625 156,250 - 1,600 27,080 2,400 800 1,200 1,600 2,000 5,475 42,155 114,095 270 96,490 59,760 62 3 30,600 306,000 - 2,300 27,080 2,400 800 1,200 3,200 2.300 9,400 48,680 257,320 528 145,170 317,080 218 4 24,000 240,000 - 1,600 27,080 2,400 800 1,550 3,000 2,000 9,875 48,305 191,695 396 193,475 508,775 263 5 21,168 211,680 - 2,300 27,080 2,400 800 1,200 3,000 2,300 9,000 48,080 163,600 340 241,555 672,375 278 TO- 91,393 913,930 34,635 10,100 120,270 11,600 4,000 6,500 10,800 9,900 33,750 241,555 672,375 278 TAL Assumptions: Plant population per hectare (625 plants); Year 2 - first cycle of harvest (mother plants) with an average weight per bunch of 25 kgs; Year 3 - second and third cycles (ratoons) of harvest with an average weight per bunch of 25 kgs; Year 4 - fourth and fifth cycles of harvests with an average weight per bunch of 20 kgs; Year 5 - sixth and seventh cycles of harvest with an average weight per bunch of 18 kgs; Farm gate price, Php10.00/kg; 2% decrease in number of mats due to virus infection on the 4th to the 5th year. -

Winter Fancy Food Show 2020 19(Sun.)– 21(Tue.)January 2020 Moscone Center South Hall Booth 850-869, 950-965

Winter Fancy Food Show 2020 19(Sun.)– 21(Tue.)January 2020 Moscone Center South Hall Booth 850-869, 950-965 864 865A GINBIS CO., LTD. 964 965 ROKKO BUTTER CO., LTD. SANRIKU CORPORATION CO., LTD. MANRAKU CORP. 865B HEART CORPORATION 862A KANEI HITOKOTO SEICHA INC. 863A SEIKA FOODS C0., LTD. 962 963 HACHIYOSUISAN CO., LTD. HIRAMATSU SEAFOODS CO., LTD. AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION CORPORATION 862B KAGURA-NO-SATO CO., LTD. 863B EIWA AMERICA INC. 861 960 TOMODA SELLING & 860A ISLE CO., LTD. 961A SAILING CO., LTD, JAPAN TACOM SR FOODS CORPORATION 860B TOKUNAGA SEIKA CO., LTD. 961B KONDO HONEY FACTORY 858 859 958 959 MIYANO FOODS CO., LTD. SUGIMOTO CO., LTD. TSUNO RICE FINE CHEMICALS CO., LTD. YUZU PREMIUM JAPAN 856 857A YAMAMOTO KAJINO CO., LTD. 956A AJIKYOU CO., LTD. 957 ITO BISCUITS CO., LTD. NAKATA FOODS CO., LTD. 857B MICHIMOTO FOODS CO., LTD. 956B MARUYA CO., LTD. 854 855 954A KAMEYA FOODS CORPORATION 955 NANAO CONFECTIONERY CO., LTD. KITAGAWAMURA YUZU OUKOKU ONISI FOODS CO., LTD. 954B OHYAMA FOODS C0., LTD. 852 853 952 953 MOCHI CREAM JAPAN CO., LTD. MOMIKI INC. UMAMI INSIDER POSEIDON GROUP INTERNATIONAL, INC. 850 851A YAMADAI FOOD CORPORATION 950 ST. COUSAIR, INC. KANEKU CO., LTD. JETRO 851B TANAKASHOKU CO., LTD. Seafood/ Milk / Rice/ Processed Food Processed Seafood Product Confectionery Seasoning Dairy Products Tea Beverages Alcoholic Beverages Processed Rice ©2020 Japan External Trade Organization(JETRO) Winter Fancy Food Show 2020 863B EIWA AMERICA INC. 865A GINBIS CO., LTD. 865B HEART CORPORATION 19(Sun.)– 21(Tue.)January 2020 Moscone Center South Hall Booth 850-869, 950-965 MATCHA Marshamllow ASPARAGUS BISCUITS ENG PKG Japanese Garden MIYANO FOODS MOCHI CREAM JAPAN NANAO CONFECTIONERY TOKUNAGA SEIKA 856 ITO BISCUITS CO., LTD. -

Filipino Cuisine; a Blending of History

RECIPE Maruya (Plantain with Jackfruit Fritters) Ingredients: 1 cup all purpose flour ½ cup sugar TasteTRENS PROCTS N MORE FROM NEL ES® FOOS gy 1 tsp. baking powder l ¼ tsp. salt 1 egg March 2018 1 cup fresh milk 2 Tbsp. melted butter CULINARY SPOTLIGHT 1 cup vegetable oil 5-6 pieces of plantain (saba) bananas, Filipino Cuisine; A Blending Of History ripe but firm, peeled and mashed Numerous indigenous Philippine cooking North America and spread to Asia in the 1 ½ cups of jackfruit (langka), diced methods have survived the many foreign 15th century. The Spanish also brought influences brought about either by trade, varied styles of cooking, reflecting the Directions: contact, or colonization. different regions of their country. Some 1. In a bowl, sift together flour, ¼ cup of these dishes are still popular in the of the sugar, baking powder, and salt. 2. In a larger bowl, beat egg. Add The first and most persistent food influence Philippines, such as callos, gambas, and milk, butter and whisk together until was most likely from Chinese traders who paella. were already present and regularly came blended. to Philippine shores. They pre-dated Some other delicacies from Mexico also 3. Add flour mixture to milk mixture Portuguese explorer Ferdinand found their way to the Philippines and stir until just moistened. Do not Magellan’s landing on due to this colonial period. overmix! Homonhon Island in Tamales, pipian, and 4. Mix the bananas and jackfruit in a 1521 by as many as balbacoa are a few separate bowl and combine with the batter mixture. -

PALABRAS EN CONFLUENCIA Cincuenta Y Un Poetas Venezolanos Modernos

PALABRAS EN CONFLUENCIA Cincuenta y un poetas venezolanos modernos Prólogo de Gabriel Jiménez Emán Fundación Editorial El Perro y la Rana 1 Prólogo Confluencias de la poesía venezolana No creo que sea ocioso preguntarse hoy cuál puede ser la función de la poesía, el papel que cumple el poema dentro del concierto de las artes o las disciplinas estéticas. Más bien se trata de una pregunta apremiante, si atendemos a los mensajes emitidos por un mundo que se ufana en perfeccionar su tecnología, sus máquinas, artefactos y aparatos para que éstos nos procuren --en teoría-- la comodidad, o en todo caso la facilidad o la rapidez para resolver asuntos que antes podían ser verdaderos problemas, enigmas incluso. La tecnología de punta se ha encargado de facilitarnos la velocidad en la comunicación, nos ha simplificado procesos, reducido distancias, para instalarnos en realidades paralelas o virtuales con sólo oprimir botones o manipular monitores. De este modo procesos que no requieren de máquinas, como el de la lectura de textos o escritura de palabras, se han ido alejando o marginando de la vida cotidiana en las grandes ciudades, como no fuera para redactar esquelas, hojear diarios o revistas ligeras, mirar titulares o avisos publicitarios. Ciudades que pueden ser megalópolis, metrópolis o ciudades pequeñas, pues en campos o en vastas extensiones de tierra que constituyen selvas, llanuras, sembradíos, pampas o terrenos nevados, se cumplen a diario ciclos ecológicos donde animales, plantas, ríos, montañas y mares celebran procesos donde la vida humana tiene lugar como partícipe (y no como centro) de esos ciclos, y como observadora de estos procesos. -

Kwentong Covid/Kwentong Obrero E-Book

KwentongCovid/ KwentongTrabaho Front cover illustration by Luigi Almuena KwentongCovid/ KwentongTrabaho Isang koleksyon ng ilang kwento at kuru-kuro tungkol sa trabaho sa panahon ng pandemya ng mga karaniwang Pilipino. Kwentong Covid/Kwentong Trabaho First edition Published in 2021 Institute for Occupational Health and Safety Development (IOHSAD) Website: https://iohsad.com E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this e-book may be reproduced or used in any form or means of—graphic, electronic or mechanical—including printing, recording, scanning or through information storage retrieval system without written permission from the creator of the original works. Copyright of the works in this publication belongs to the respective authors and artists. PUBLICATION TEAM Teo S. Marasigan Editor Dino Brucelas Design Nadia De Leon Coordinator Nilalaman/Contents Ako si Olib/55 Oliver Muya PAUNANG SALITA/10 Nadia De Leon Walang Puwang ang Masipag na Manggagawa sa Mata ng Kapitalista/57 INTRODUKSYON/14 Emily Barrey Dadalhin Kita sa Covid/Trabaho Teo S. Marasigan Pakikibaka sa Ilalim ng Pandemya/60 Rodne T. Baslot EMPRESA-KUMPANYA-OPISINA Sa Ngalan ng Iyong Duguang Baro/61 No Work, No Pay sa Gitna ng Pandemya/26 Raymund B. Villanueva Arth Jay Murillo Ang Pag-oorganisa sa Ilalim ng Pandemya/62 Pumasok na Ako Ngayon sa Opis /29 PJ Dizon Beverly Wico Sy Mga Aninong Nagtatago sa Birheng Antique/65 Isang Taon na ang Problema Mo/36 Iggie Espinoza Dennis S. Sabado Pepe/71 May mga Madaling Araw na Gaya Nito/43 Kamz Deligente Paul Joshua Morante PAARALAN T’wing A-kinse’t A-trenta/44 John Ahyet Marcelo Santos Yana, ang Titser-Nanay sa Gitna ng Pandemya/76 Diane Capulong Resume/46 Ariel Tua Rivera A Noble Act in the Time of Covid-19/84 Jeffrey G. -

Sama Esan&Ngiv Filipino English

Manga b I Sama ESan&ngiV Filipino English Manga Bissara Sama Bangingi' Filipino English Revised Second Edition SUMMER INSTITUTE OF LINGUISTICS- Philippines Inc. TR4NSLATORS 1993 PUBLISHERS Published in cooperation with the Conlnlission on Philippine Languages and the Department of Education, Culture and Sports Manila, Philippines Additional copies of this publication may be obtained from: Book Depository P.O. Box 2270 CPO 1099 Manila This book or any part thereof may be copied or adapted and reproduced for use by any entity of the Department of Education, Culture and Sporta without permiesion from the Summer Institute of Linguiatice. If there are other organizations or agencies who would like to copy or adapt this book we request that penniesion first be obtained by writing to: Summer Institute of Linguistics P.O. Box 2270 CPO 1099 Manila Balangingi' Sama Vocabulary Book First Edition 1980 - 4C Second Printing 1980 - 3C Revised Second Edition 1993 - 6C 71.14-93-5C 82.120-934029N ISBN 971-18-0232-5 Printed in the Philippines SIL Press REYUULIKA NGPlLlYlNAS RIPUDUC OP~IErnlwvrinrs KACAWARAN NG EDUKASYON. KULTURA AT ISPORTS DEPARSUEHT OF EDUCATION. CULNU AND WONTS UL Compla, Munlcu Avenue Purig. MrhManib PAUNANG SALITA Ang mga iala, kagubatan at mga kabundukan ng ating barn ay tahanan ng iba't-ibang parnayanang Mtural na ang bawat isa ay may sariling wika at kaugalian. Ang ating Mtura ay mah&+ng piraso ng iaang rnagandang mceaik - iyan ang bansang Pilipinas. Ang ating bansa ay mayroong utang na loob sa pamayanang kultural. -ling panahon na ang nagdaan na ang kaugahan, wika at rnagandang layunin ay nakatulong sa ikauunlad ng ating makabamang pagkamamamayan. -

FDA Philippines - Prohibited Items Updated October 21, 2020

FDA Philippines - Prohibited Items Updated October 21, 2020 A & J Baguio Products Pure Honey Bee A & W Change Lip Gloss Professional A & W Waterproof Mascara Long Lash-Run Resistant A Bonne’ Milk Power Lightening Lotion + Collagen Double Moisturizing & Lightening A&W Smooth Natural Powder (1) A. Girl® Matte Flat Velvet Lipstick A.C Caitlyn Jenner Powder Plus Foundation Studio Mc08 Aaliyah'S Choco-Yema Spread Aaliyah'S Roasted Peanut Butter, Smooth Original Aaliyah'S Rocky Roasted Peanut Butter Spread, Rocky Nuts Aamarah’S Beauty Products Choco Berry Milk Super Keratin Conditioner With Aloe Vera Extract Ab Delicacies Breadsticks Ab Delicacies Fish Cracker Ab Delicacies Peanut Ab Delicacies Pork Chicharon Abby’S Delicious Yema Abc Crispy Peanut And Cashew Abrigana Fish Crackers Snack Attack Absolute Nine Slim Ac Makeup Tokyo Oval Eyebrow Pencil N Ac Makeup Tokyo Eyebrow Pencil Dark Brown Acd Marshmallows Acd Spices Flavorings,Cheese Powder Ace Edible Oil Ace Food Products Serapina Aceite De Alcanfor 25Ml Achuete Powder Acne Cure Clarifying Cleanser With Tea Tree Oil Acnecure Pimple Soap Active White Underarm Whitening Soap Ad Lif Herbal Juice, Graviola Barley,Moringa Oleifera Fruits And Vegetables Ade Food Products Korean Kimchi Chinese Cabbage Ade’S Native Products Buko Pie Adelgazin Plus Adorable Cream Bar Chocolate Flavor Ads Fashion Blusher (A8408) (3) Advanced Formula L-Glutathione White Charm Food Supplement Capsule Advanced Joint Support Instaflex Advanced Featuring Uc-Ii® Collagen Dietary Supplement Aekyung 2080 Kids Toothpaste Strawberry African Slim African Mango Extract African Viagra 4500Mg Ageless Bounty Resveratrol 1000Mg Advance Agriko 5 In 1 Tea Juice Extract Agriko 5 In 1 Turmeric Tea Powder With Brown Sugar Agriko 5 In 1 Turmeric Tea Powder With Brown Sugar Agua (Cleansing Solution) 60Ml Agua Boo Purified Drinking Water Agua Oxigenada F.E.U. -

Plant Resources of South-East Asia Is a Multivolume Handbook That Aims

Plant Resources of South-East Asia is a multivolume handbook that aims to summarize knowledge about useful plants for workers in education, re search, extension and industry. The following institutions are responsible for the coordination ofth e Prosea Programme and the Handbook: - Forest Research Institute of Malaysia (FRIM), Karung Berkunci 201, Jalan FRI Kepong, 52109 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia - Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Widya Graha, Jalan Gatot Subroto 10, Jakarta 12710, Indonesia - Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources (IEBR), Nghia Do, Tu Liem, Hanoi, Vietnam - Papua New Guinea University of Technology (UNITECH), Private Mail Bag, Lae, Papua New Guinea - Philippine Council for Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resources Re search &Developmen t (PCARRD), Los Banos, Laguna, the Philippines - Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research (TISTR), 196 Phahonyothin Road, Bang Khen, Bangkok 10900, Thailand - Wageningen Agricultural University (WAU), Costerweg 50, 6701 BH Wage- ningen, the Netherlands In addition to the financial support of the above-mentioned coordinating insti tutes, this book has been made possible through the general financial support to Prosea of: - the Finnish International Development Agency (FINNIDA) - the Netherlands Ministry ofAgriculture , Nature Management and Fisheries - the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Directorate-General for Inter national Cooperation (DGIS) - 'Yayasan Sarana Wanajaya', Ministry of Forestry, Indonesia This work was carried out with the aid of a specific grant from : - the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa, Canada 3z/s}$i Plant Resources ofSouth-Eas t Asia No6 Rattans J. Dransfield and N. Manokaran (Editors) Droevendaalsesteeg 3a Postbus 241 6700 AE Wageningen T r Pudoc Scientific Publishers, Wageningen 1993 VW\ ~) f Vr Y DR JOHN DRANSFIELD is a tropical botanist who gained his first degree at the University of Cambridge. -

PAMPANGA CUISINE PLUS 400 Queen St

PAMPANGA CUISINE PLUS 400 Queen St. West L6X1B3, Tel. 905-4558655 www.pampangacuisinebrampton.ca Store Hours: Close on Monday,Tue-Saturday 10am-8Pm,Sunday 10am-5Pm Party Tray Sizes Small Tray 10-15 servings,Medium Tray 20-30 servings,Large 40-50 servings BEEF SMALL MEDIUM LARGE AFRITADA $45 $65 $105 BEEF STEAK $45 $65 $105 BEEF KARE-KARE $45 $65 $105 OX TAIL KARE-KARE NA $75 $115 BOPIS $45 $65 $105 CALDERETA $45 $65 $105 MECHADO $45 $65 $105 PAPAITAN $45 $65 $105 BEEF BROCCOLI $45 $65 $105 PORK SMALL MEDIUM LARGE AFRITIDA $30 $45 $80 ADOBO $30 $45 $80 BICOL EXPRESS $30 $50 $85 BINAGOONGAN $35 $50 $85 DINUGUAN $30 $45 $85 IGADO $30 $45 $80 KARE-KARE $35 $50 $85 LECHON PAKSIW $30 $45 $85 MECHADO $30 $45 $85 MENUDO $30 $45 $80 POCHERO $30 $45 $80 PORK STEAK $30 $45 $85 SISIG $35 $50 $85 SWEET& SOUR PORK $30 $45 $80 TOKWAT BABOY $35 $50 $85 CRISPY PATA varies LECHON KAWALI $8.99/lb PORK BBQ SKEWER $1.75/lpc CHICKEN SMALL MEDIUM LARGE ADOBO $30 $45 $80 AFRITADA $30 $45 $80 CHICKEN CURRY $30 $45 $80 CALDERETA $30 $45 $80 POCHERO $30 $45 $80 Chicken BBQ Skewer $2.25/pc FLIP PAGE FOR MORE VEGETABLE TORTANG TALONG $4/pc PINAKBET $25 $45 $75 CHOPSUEY $25 $40 $75 GINATAANG KALABASA $25 $40 $75 GINATAANG LAING $30 $45 $80 GINATAANG LANGKA $30 $45 $80 NOODLES SMALL MEDIUM LARGE PANCIT CANTON $30 $40 $75 PANCIT BIHON $25 $35 $65 PANCIT PALABOK $30 $40 $75 PANCIT SOTANGHON $25 $35 $65 SPAGHETTI $30 $45 $80 SEAFOODS SMALL MEDIUM LARGE CALAMARI $35 $50 $85 ADOBONG PUSIT $35 $50 $90 INIHAW NA PUSIT varies w/ market price INIHAW NA BANGUS DAING NA BANGUS -

D) That's an Order! (1/2

(D) That’s an Order! (1/2) Cebuano is an Austronesian language spoken in the Philippines. The language was heavily influenced by Spanish during a period of colonialism from 1521 to 1898. Your task is to figure out what four women, Althea, Inday, Janelle, and Maria, had for lunch. Each person had a main dish as well as a dessert and a drink. No two people ordered the same main dish, no two people or- dered the same dessert, and no two people ordered the same drink. Each of them chose from the following Philippine menu : Main Dishes adobong baboy: Pork dish cooked in soy sauce, vinegar, and garlic. adobong sitaw: String beans cooked in the adobo style (with soy sauce and vinegar). asado: Beef dish cooked in a sauce with tomatoes, olives, onion, ketchup, red bell pepper, and potatoes. bulanglang: Boiled mixed vegetables, including malunggay leaves, squash and onions in rice washing. Desserts buko pie: A traditional Filipino baked young coconut custard pie. kutsinta: A type of steamed rice cake made with rice flour, brown sugar and lye. maruya: Banana fritters, served in syrup or ice cream. turon saba: Deep fried plantains in spring roll wrappers. Drinks bino: Wine. gatas: Milk. serbesa: Beer. tubig: Water. D1. Based on the following clues try to determine who ordered which food and drink. Write your answers in Cebuano on the next page. Janelle nikaon og bulanglang apan dili og turon saba. Ang tao nga nipalit og asado ug nikaon og kutsinta wala niinom og serbesa. Ang tao nga nikaon og adobong baboy ug niinom og tubig apan si dili Althea.