Final Project Report Submitted to Azim Premji University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessment of Water Quality for Groundwater in Thullur Mandal, Guntur District, A.P, India

April 2017, Volume 4, Issue 04 JETIR (ISSN-2349-5162) ASSESSMENT OF WATER QUALITY FOR GROUNDWATER IN THULLUR MANDAL, GUNTUR DISTRICT, A.P, INDIA 1P. Akhil Teja, 2V. Jaya Krishna, 3CH. Manikanta, 4M. Musalaiah 1, 2, 3 Final B.Tech Students, 4Assistant Professor, 1Department of Civil Engineering, 1MVR College of Engineering and Technology, Paritala, Andhra Pradesh, India Abstract— Groundwater is an essential and valuable natural source of water supply all over the world. To meet out the rising demand it is crucial to identify and recognize the fresh water resources and also to find out remedial methods for improvement of water quality. So, assessment of ground water quality has always been paramount in the field of environmental quality management. Physico-chemical parameters of groundwater quality based on physic-chemical parameters plays a prominent role in evaluating its suitability for drinking purpose. The present study deals with the determination of water quality index of Thullur mandal, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, in order to ascertain the quality of Groundwater for public consumption, recreation and other purposes. The samples were collected from all 19 villages of Thullur mandal. The samples were analyzed in the laboratory using standard APHA 1985 procedures. From the analyzed data, WQI has been calculated using Weighted Average method. The variations of water quality on different samples were also discussed. Index Terms— Groundwater, Water Quality Parameters, Sampling, Water Quality Standards, Water Quality. 1. INTRODUCTION Water is the most important natural resource, which forms the core of ecological system. Recently there has been overall development in various fields such as agriculture, industry and urbanization in India. -

World Bank Document

Amaravati Sustainable Capital City Development Project Resettlement Policy Framework Amaravati Sustainable Capital City Development Project (ASCCDP) Public Disclosure Authorized Final Final Draft Resettlement Policy Framework Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority (APCRDA) Government of Andhra Pradesh, Amaravati July 2018 Version 5 Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Amaravati Sustainable Capital City Development Project Resettlement Policy Framework Contents ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... 4 I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Background .................................................................................................................................................... 12 Need for Resettlement Policy Framework ................................................................................................. 12 Amaravati Capital City development and the World Bank supported Project .................................... 13 II. LAND ASSEMBLY INSTRUMENTS ............................................................................................................ -

IJCIET 09 05 104.Pdf

International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET) Volume 9, Issue 5, May 2018, pp. 948–954, Article ID: IJCIET_09_05_104 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJCIET?Volume=9&Issue=5 ISSN Print: 0976-6308 and ISSN Online: 0976-6316 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed AN EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH TO RAISE THE IRRIGATION STANDARDS FOR IMPROVING CROP PRODUCTIVITY AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT BY USING GEO SPATIAL TECHNOLOGY – A MODEL STUDY M. Satish Kumar Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Kallam Haranadha Reddy Institute of Technology, Chowdavaram, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India. Pathan Nagul meera, Sayyad Moulali and Shaik Shareef B.Tech Student Department of Civil Engineering, Kallam Haranadha Reddy Institute of Technology, Chowdavaram, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India. P. Pavan Kumar, Syed Anwar basha and R Siva Ganesh Goud B.Tech Student Department of Civil Engineering, Kallam Haranadha Reddy Institute of Technology, Chowdavaram, Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India. ABSTRACT In the current world scenario information has become almost instantaneous as the world is moving forward with rapid changes due to the advancement in science and technology. In spite of these relevant changes there are certain basic needs which never change the over exploding population and growing needs are increasing pressure on the available natural resource, apart from these the un-even distribution of rainfall makes the situation more complicated to promote sustainable development. In the developing countries like India there is an immediate -

Immediately Election Commission of In

FTO BE PUBLISHED IN THE EXTRAORDINARY ISSUE OF THE GAZETTE OF INDIA PART II SECTION 3(iii) IMMEDIATELY ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi-110 001 No. 464/EPS/2019/7A(1) Dated: the 8th April, 2019 18 Chaitra, 1941(Saka) NOTIFICATION In pursuance of sub-rule (2) of Rule-11 of the Conduct of Elections Rules, 1961, the list of contesting candidates for the Parliamentary Constituencies Scheduled for poll on 11th April, 2019 for the General Election to Lok Sabha, 2019 is published for general information. By Order, (SUMIT MUKHERJEE) Principal Secretary FORM 7-A (See Rule 10(1)) LIST OF CONTESTING CANDIDATES Election to the House of the People from the 01-Araku (ST) Parliamentary Constituency Sl. Name of the candidate Address of the Symbol Party affiliation No. candidate Allotted 1 2 3 4 5 (i) Candidates of Recognised National and State Political Parties KISHORE CHANDRA The Fort-Kurupam, DEO Sivannapeta Village, Kurupam Mandal, 1 Telugu Desam Bicycle Vizianagaram District, Pin:535524, Andhra Pradesh Dr. KOSURI KASI VISWANADHA VEERA VENKATA SATYANARAYANA D. No. 2-26, REDDY Goragummi Village & Post, Gangavaram Bharatiya Janata 2 Lotus Mandal, East Godavari Party District, Andhra Pradesh GODDETI. MADHAVI Sarabhanna Palem Post & Village, Koyyuru Mandal, Yuvajana Sramika Ceiling 3 Visakhapatnam Rythu Congress Party Fan Distrcit, Pin:531084, Andhra Pradesh SHRUTI DEVI VYRICHERLA 11-131, The Fort Kurupam, Sivannapeta Hamlet, Kurupam Indian National 4 Hand Panchayat and Mandal, Congress Vizianagaram Distrcit- 535524 (ii) Candidates of registered Political parties (other than recognised National and State Political Parties) GANGULAIAH VAMPURU. Sundruputtu Village, Paderu Panchayat, Paderu Mandal, Glass 5 Janasena Party Visakhapatnam Tumbler Distrcit, Pin:531024, Andhra Pradesh SWAMULA. -

WE ARE COMMITTED to UPLIFTING Bcs: CM

Follow us on: RNI No. APENG/2018/764698 @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer Established 1864 Published From NATION 5 MONEY 8 SPORTS 12 VIJAYAWADA DELHI LUCKNOW WITH SENA BY HER SIDE, GOVT TO PROFESSIONALISE WEKE UP BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH SONIA CALLS OUT MODI, SHAH BSNL AND MTNL: PRASAD PANT BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN HYDERABAD *Late City Vol. 2 Issue 28 VIJAYAWADA, FRIDAY NOVEMBER 29, 2019; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable I DISLIKE THAT PEOPLE ARE CELEBRATING AT MY COST: VD { Page 9 } www.dailypioneer.com JOTIBA PHULE’S BIRTH ANNIVERSARY Pressure govt to resume Capital works: Naidu calls upon people SEELAM AROZI Will submit WE ARE COMMITTED n VIJAYAWADA Coming down heavily on the report soon: panel YSRCP government for what he called killing the Amaravati project, Telugu Desam Party on capital city TO UPLIFTING BCs: CM (TDP) president N VIJAYAWADA:Experts' PNS n VIJAYAWADA The Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu has said Committee on Capital and that it is a self-financed project State's Development met Chief Minister YS said his government conceived by him to develop a Chief Minister YS Jaganmohan Reddy has said will extend support world-class Capital for Andhra Jaganmohan Reddy on while the Indian economy is to the SCs, STs, BCs & Pradesh. Addressing a meeting Thursday at Camp Office, in a downward trend due to at Mandadam in the Capital Tadepalli and briefed him recession and unemployment minorities till they region on Thursday after under- on issues found by them in rising, Andhra Pradesh has are fully uplifted. taking a tour of the Capital their study tour. -

Nl'1,1 Cid- R-.Srjn Strike Off Part I Or Part II Below Whichever Is Not Applicable Za\Nr[Xu [Rc PART

FORM 2A (See Rule 4) NOMINATION PAPER Election to the House of the People Nl'1,1 CId- r-.srJn Strike off Part I or Part II Below whichever is not applicable za\nr[xu [rc PART. I (To be used by candidate set up by recognized political party) I nominate as a candidate for election to the House of the People from the IS-BAPATLA (SC) Parliamentary Constituency. Candidate,snameBABYLATHA.NANDIGAMMHusband,sname SURESH . NANDIGAM His postal address 2-619 Uddandurayunipalem Village, Thulluru Mandal, Guntur District. His name is entered at Sl. No. 36 in Part No 19 of the electoral roll for 86-TADIKONDA (SC) (Assembly constituency comprised within) l3-GUNTUR /' Parliamentary Constittiency. My name is Raj Kumar Chandolu and it is entered in Sl.No.lll in Part No. 228 of the electoral roll for the 105 - Addanki Assembly constituency comprised within 15- Bapatla Parliamentary constituency. Date: Signature of Proposer PART II We nominate as candidate for the House Parliamentary :ituency. Ca 's name Father's / Mether'Y usband's name H|6 postal address Her name is entered at No in Part No of the electo roll for ........( bly constituency comprised within. Parliamentary Consti We that we are electors of the above liamentary constituency names are in the electoral roll for this Parli tary constituency as ind below and we our signatures below the token of ibing to this nomination: Particulars of the proposes and their signatures Name of Elector Roll No. of Component Proposer S. assembly Part No. No. constituency of Sl. No. Full Name Signature Date in that Electoral part Roll I 2 J 4 5 6 7 I NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL 2 NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL J NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL 4 NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL 5 NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL 6 NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL 7 NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL 8 NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL 9 NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL 10 NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NIL NB : There should be ten electors of the constituency as proposers. -

18-19-20 November 2020

English Monthly from Hyderabad, India Health•Nutrition•Management•Processing•Marketing Estd. 1993 Annual Subscription: Rs 800 Foreign $ 100 RNI Regn. No. 52899/93 August 2020 Editorial: Work with long term perspective for the industry and for yourself ! Build Amaravati as the pride Capital of A.P in India th 35 Edition from NRS Group Centre targets scaling up the fisheries sector to help India achieve $ 5 trillion economy 1 8 - 19-20 November 2020 HITEX Exhibition Centre Hitech City, Izzatnagar, Kondapur, Hyderabad, India. Exhibition and Conference on Aquaculture to Update Knowledge and for Better Business Opportunities Shrimp giants urged to take action over increased disease risks Aquaculture farmers of Andhra Pradesh stare at heavy losses despite rise in production Japan lifts inspection order for Black Tiger shrimps from India Recognition to the Organizations and CMFRI adjudged as best Individuals for the Excellence and Contribution to Aquaculture Sector research institute under ICAR Contact For Participation Haryana to give 10% subsidy for fisheries Aquaculture in perspective of Corona virus with emphasis on production optimization and supply Online Edition: www.aquainternational.in AI AUGUST 2020 ISSUE.indd 1 10-08-2020 18:43:24 2 • AQUA INTERNATIONAL • August 2020 AI AUGUST 2020 ISSUE.indd 2 10-08-2020 18:43:25 August 2020 • AQUA INTERNATIONAL • 3 AI AUGUST 2020 ISSUE.indd 3 10-08-2020 18:43:25 4 • AQUA INTERNATIONAL • August 2020 AI AUGUST 2020 ISSUE.indd 4 10-08-2020 18:43:26 August 2020 • AQUA INTERNATIONAL • 5 AI AUGUST 2020 ISSUE.indd 5 10-08-2020 18:43:27 SELSAF PROTECTION TWO IS BETTER THAN ONE The information provided in this document is at the best of our knowledge, true and accurate. -

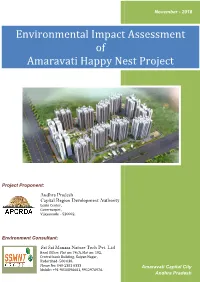

Environmental Impact Assessment of Amaravati Happy Nest Project

November - 2018 Environmental Impact Assessment of Amaravati Happy Nest Project Project Proponent: Andhra Pradesh Capital Region Development Authority Lenin Center , Governorpet , Vijayawada - 520002. Environment Consultant: Sri Sai Manasa Nature Tech Pvt. Ltd Head Office: Plot no: 74/A, Flat no: 102, Central bank Building, Kalyan Nagar, Hyderabad- 500 038. Phone No: 040-2381 6333 Mobile: +91-9010896661, 9912976976. Amaravati Capital City Andhra Pradesh Table of Contents Content Page No Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose of the Report 1 1.2 Identification of Project & Project Proponent 1 1.3 Importance of the Project 3 1.4 Scope of the Study 5 1.5 Applicable Environmental Standards and Regulation 5 1.6 Benefits of the Project 6 Chapter 2 Project Description 2.1 Type of Project 7 2.2 Need for the Project 7 2.3 Location of the Project 7 2.4 Size or Magnitude of Operation 12 2.5 Proposed Schedule of Operation 15 2.6 Requirements of the project 15 Chapter 3 Description of the Environment 3.1 Study Area 20 3.2 Scope & Methodology of EIA Study 20 3.3 Baseline Environment 21 Chapter 4 Anticipated Environmental Impacts and Mitigation Measures 4.1 Introduction 43 4.2 Land Environment 44 4.3 Air Environment 45 4.4 Water Environment 47 4.5 Noise Environment 49 4.6 Solid Waste Generation 49 4.7 Storm Water Management & Rainwater Harvesting 51 4.8 Greenbelt Development 51 4.9 Hazardous Waste 51 4.10 E-Waste 52 4.11 Parking Place 52 4.12 Socio Economic Environment 53 4.13 Energy Conservation & Green Building Measures 55 4.14 Fire Fighting System 57 -

Amaravati Capital City Development Project

AMARAVATI CAPITAL CITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FINAL SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT UDDANDARAYUNIPALEM VILLAGE JULY 2016 SUBMITTED BY: ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION TRAINING & RESEARCH INSTITUTE SURVEY NO.91/4, GACHIBOWLI HYDERABAD – 500 032 TELANGANA Final SIA Report for the Amaravati Capital City Development Project – Uddandarayunipalem (V) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary of Uddandarayunipalem Village 01 1.0. Project and Public Purpose 01 1.1. Location 02 1.2. Size attributes of Land Acquisition 02 1.3. Social Impacts 06 1.4. Mitigation Measures 07 1.4.1. Green & Blue lattice 07 1.4.2. Primary green spaces 08 1.4.3. Secondary green links 08 1.4.4. Recreational Landscapes 08 1.4.5. Water bodies 08 1.4.6. Benefits for the Project Affected Persons 08 1.5. Impact on Livelihoods 09 1.5.1. Mitigation Measures 09 1.6. Impact on Utilities 09 1.6.1. Mitigation Measures 09 1.7. Impact during Construction Phase 10 1.7.1. Mitigation Measures 10 1.8. Assessment of Social Cost & Benefits 11 2. Detailed Project Description 12 2.0. Background 12 2.1. Nature, Size and Location of the Project 13 2.1.1. Geographic Positioning of Amaravati 14 2.2. Transport Connectivity 14 2.2.1. Project Overview 16 2.3. Goals and Strategies 17 2.4. Developmental Phasing 19 2.5. Applicable Legislation and Policies 21 3. Team and Composition, Approach and Schedule for SIA 23 3.0. Team Composition 23 3.1. Objectives and Scope of the study 23 Final SIA Report for the Amaravati Capital City Development Project – Uddandarayunipalem (V) 3.2. -

A Case of the Abusive, Greedy and Failing Amaravati Capital City Project (2014-2019) Research: Tani Alex Layout: Ankit Agrawal

Encroachment of Nature, People and Livelihoods: A Case of the Abusive, Greedy and Failing Amaravati Capital City Project (2014-2019) Research: Tani Alex Layout: Ankit Agrawal Published by: Centre for Financial Accountability New Delhi www.cenfa.org [email protected] Cover Photo: Rahul Maganti/PARI April 2019 Copylef: Free to use any part of this document for non-commercial purpose, with acknowledgement of source. For Private Circulation Only Encroachment of Nature, People and Livelihoods: A Case of the Abusive, Greedy and Failing Amaravati Capital City Project (2014-2019) 3 Background of the Amaravati Project (2014-2017) Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid the foundation of the Amaravati Capital City Project. Photo courtesy: AP Capital Region Development Authority fer bifurcation of the erstwhile Indian crops irrigated on the foodplains. Te area sited for state of Andhra Pradesh in June 2014, both the city presently has a population of 1.03 lakh while the new states of Telangana and Andhra that of the entire capital region would be 5.8 million. APradesh are sharing the Hyderabad as capital for 10 years. In September 2014, N Chandrababu Naidu, Te following contraventions of this project are the Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh announced elicited, during 2014-2017, with regard to World that a single capital would be built for the State. Bank’s Operational Policies, in a concentrated efort to prevent forthcoming irreplaceable damages to Amaravati, the proposed capital city covers an area peoples’ lives. World Bank’s Operational Policies of 217. 23 sq. km with the seed capital in an area of framework have been employed here as AIIB has 16.94 sq. -

High Court of Andhra Pradesh :: Amaravati

HIGH COURT OF ANDHRA PRADESH :: AMARAVATI **** WRIT PETITION No.8890 OF 2020 Between: Kantamaneni Ravishankar. … Petitioner And The State of Andhra Pradesh, Represented by its Principal Secretary, Home Department, A.P.Secretariat, Velagapudi, Amaravathi, Guntur District and others … Respondents. JUDGMENT PRONOUNCED ON 26.08.2020 THE HON’BLE SRI JUSTICE M.SATYANARAYANA MURTHY 1. Whether Reporters of Local newspapers may be allowed to see the Judgments? No 2. Whether the copies of judgment may be marked to Law Reporters/Journals Yes 3. Whether Their Ladyship/Lordship wish to see the fair copy of the Judgment? Yes MSM,J WP_8890_2020 2 * THE HON’BLE SRI JUSTICE M.SATYANARAYANA MURTHY + WRIT PETITION No.8890 of 2020 % 26.08.2020 # Kantamaneni Ravishankar. ….Petitioner v. $ The State of Andhra Pradesh, Represented by its Principal Secretary, Home Department, A.P.Secretariat, Velagapudi, Amaravathi, Guntur District and others …. Respondents ! Counsel for the Petitioners : Sri A.Radha Krishna Counsel for Respondents: Government Pleader for Home <Gist : >Head Note: ? Cases referred: 1. (2014) 8 SCC 273 2. AIR 2020 SC 1308 3. 1992 (3) SCC 637 4. 1995 (2) SCC 161 5. AIR 1954 SC 440 6. AIR 1958 SC 956 7. AIR 1973 SC 1461 8. AIR 1930 Lahore 465 9. AIR1977SC1489 10. 104 (2003) DLT 510 11. (1992) 1 AC 34 12. (1994) 181 CLR 251 13. (2011) HCA 50 MSM,J WP_8890_2020 3 14. AIR2007SC976 15. 2000 (8) SCC 590 16. 1994 Cri L J 2320 17. AIR 1964 All 481 18. 1997 (7) SCC 431 19. 2007 (5) SCC 1 20. 1995 (3) SCC 214 21. -

Amaravati Capital City Development Project

AMARAVATI CAPITAL CITY DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FINAL SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT NELAPADU VILLAGE JULY 2016 SUBMITTED BY: ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION TRAINING & RESEARCH INSTITUTE SURVEY NO.91/4, GACHIBOWLI HYDERABAD – 500 032 TELANGANA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 01 1.0. Project and Public Purpose 01 1.1. Location 02 1.2. Size attributes of Land Acquisition 02 1.3. Social Impacts 05 1.4. Mitigation Measures 05 1.4.1. Green & Blue lattice 06 1.4.2. Primary green spaces 06 1.4.3. Secondary green links 06 1.4.4. Recreational Landscapes 06 1.4.5. Water bodies 06 1.4.6. Benefits for the Project Affected Persons 06 1.5. Impact on Livelihoods 07 1.5.1. Mitigation Measures 07 1.6. Impact on Utilities 07 1.6.1. Mitigation Measures 08 1.7. Impact during Construction Phase 08 1.7.1. Mitigation Measures 08 1.8. Assessment of Social Cost & Benefits 09 2. DETAILED PROJECT DESCRIPTION 10 2.0. Background 10 2.1. Nature, Size and Location of the Project 11 2.1.1. Geographic Positioning of Amaravati 12 2.2. Transport Connectivity 12 2.2.1. Project Overview 14 2.3. Goals and Strategies 14 2.4. Developmental Phasing 17 2.5. Applicable Legislation and Policies 19 3. TEAM AND COMPOSITION, APPROACH AND SCHEDULE FOR SIA 21 3.0. Team Composition 21 3.1. Objectives and Scope of the study 21 3.2. Approach and Methodology for Socio-Economic Studies 22 3.2.1. Phase – I: Pre Survey Activities 22 3.2.2. Phase – II: Survey Activities 23 3.3.