The International Committee of the Red Cross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War TACHIKAWA Kyoichi Abstract Why does the inhumane treatment of prisoners of war occur? What are the fundamental causes of this problem? In this article, the author looks at the principal examples of abuse inflicted on European and American prisoners by military and civilian personnel of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy during the Pacific War to analyze the causes of abusive treatment of prisoners of war. In doing so, the author does not stop at simply attributing the causes to the perpetrators or to the prevailing condi- tions at the time, such as Japan’s deteriorating position in the war, but delves deeper into the issue of the abuse of prisoners of war as what he sees as a pathology that can occur at any time in military organizations. With this understanding, he attempts to examine the phenomenon from organizational and systemic viewpoints as well as from psychological and leadership perspectives. Introduction With the establishment of the Law Concerning the Treatment of Prisoners in the Event of Military Attacks or Imminent Ones (Law No. 117, 2004) on June 14, 2004, somewhat stringent procedures were finally established in Japan for the humane treatment of prisoners of war in the context of a system infrastructure. Yet a look at the world today shows that abusive treatment of prisoners of war persists. Indeed, the heinous abuse which took place at the former Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War is still fresh in our memories. -

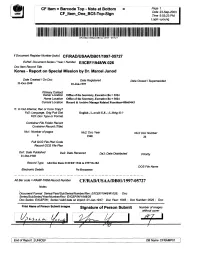

CF Item = Barcode Top - Note at Bottom = Page 1 CF Ltem One BC5-Top-Sign Date 23-Sep-2003 Time 5:03:23 PM Login Uyoung

CF Item = Barcode Top - Note at Bottom = Page 1 CF_ltem_One_BC5-Top-Sign Date 23-Sep-2003 Time 5:03:23 PM Login uyoung CF/RAD/USAA/DBOl/1997-05727 II Document Register Number [auto] CF/RAD/USAA/DB01/1997-05727 ExRef: Document Series / Year/ Number E/ICEF/1948/W.026 Doc Item Record Title Korea - Report on Special Mission by Dr. Marcel Junod Date Created/On Doc Date Registered Date Closed / Superseeded 21-Oct-1948 OWan-1997 Primary Contact Owner Location Office of the Secretary, Executive Bo = 3024 Home Location Office of the Secretary, Executive Bo = 3024 Current Location Record & Archive Manage Related Functions=80669443 11: In Out Internal, Rec or Conv Copy? Fd2: Language, Orig Pub Dist English, L.Avail: E,f..; L.Orig: E-? Fd3: Doc Type or Format Container File Folder Record Container Record (Title) Nu1: Number of pages Nu2: Doc Year Nu3: Doc Number 0 1948 26 Full GCG File Plan Code Record GCG File Plan Da1: Date Published Da2: Date Received Da3: Date Distributed Priority 21-0ct-1948 Record Type A04 Doc Item: E/ICEF1946 to 1997 Ex Bd DOS File Name Electronic Details No Document Alt Bar code = RAMP-TRIM Record Number CF/RAD/USAA/DB01/1997-05727 Notes Document Format Series/Year/SubSeries/Number/Rev: E/ICEF/1948/W.026; Doc Series/SubSeries/Year/Number/Rev:E/ICEF/W/1948/26 Doc Series: E/ICEF/W; Series Valid date on import: 01-Jan-1947; Doc Year: 1948; Doc Number: 0026; Doc Print Name of Person Submit Images Signature of Person Submit Number of images without cover iy>*L> «-*. -

A Doctor's Account

THE HIROSHIMA DISASTER - A DOCTOR'S ACCOUNT Marcel Junod was the first foreign doctor to reach Hiroshima after the atom bomb attack on 6 August 1945. Junod, the new head of the ICRC's delegation in Japan, arrived in Tokyo on 9 August 1945 - the very day that the United States dropped a second atomic bomb, this time on Nagasaki. Junod, who had been travelling for two months and had not caught up with the news, was astounded: “For the first time I heard the name of Hiroshima, the words "atom bomb". Some said that there were possibly 100,000 dead; others retorted 50,000. The bomb was said to have been dropped by parachute, the victims had been burnt to death by rays, etc...” Information was hard to come by, and Junod's immediate task was to visit Allied prisoners of war held in Japan (Emperor Hirohito's surrender broadcast came on 15 August). It was only after one of the ICRC delegates in the field sent Junod a telegram with apocalyptic details of the Hiroshima disaster that Junod could set the wheels in motion for a belated, but still vital, relief effort. On 8 September he flew from Tokyo with members of an American technical commission, and a consignment of relief provided by the US armed forces. “At twelve o'clock, we flew over Hiroshima. We... witnessed a site totally unlike anything we had ever seen before. The centre of the city was a sort of white patch, flattened and smooth like the palm of a hand. Nothing remained. -

Peace Education Materials~Toward a Peaceful World Free of Nuclear

Peace Education ~Toward a Peaceful World Free of Nuclear Weapons~ An Oasis amidst the ruins Area around the hospital, 1.5km south of the hypocenter Japanese Red Cross Society – Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital 2018Edition Contents I. Introduction 1 II. Establishing of the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital 2 III. Dropping of the A-bomb 3 IV. Testimony by two nurses who worked day and night for 6 nursing patients V. Dr. Marcel Junod's humanitarian activity 8 VI. Sadako Sasaki and the “Children's Peace Monument” 8 VII. Foundation of Hiroshima Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital 9 VIII. Memorial Park 12 IX. Supportive Activities for Atomic-bomb Survivors 15 X. Medical Treatment and Current Situation of the Patients 17 of Atomic-bomb Survivors at this Hospital I. Introduction Welcome to the Hiroshima Red Cross & Atomic-bomb Survivors Hospital. “Seventy-one years ago on a bright,cloudless morning death fell from the sky and the world was changed.”(U.S. President Barack Obama) An A-bomb was dropped on Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. of August 6, on Nagasaki at 11:02 a.m. of August 9 in1945. During the World War Ⅱ,many people living in Tokyo and other major cities in Japan were sacrificed and injured by big raids of fire bombs. A-bomb Survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki are suffering even now because of the influence of an A-bomb radiation . What was found by city doctors in Hiroshima and is now widely well known is that relatively many of the A-bomb survivors suffer from leukemia and/or cancer. -

The International Committee of the Red Cross and Chemical Warfare in the Italo-Ethiopian War 1935-1936

Force versus law: The International Committee of the Red Cross and chemical warfare in the Italo-Ethiopian war 1935-1936 by Rainer Baudendistel "Caritas inter arma" is no longer possible: this is all-out war, pure and simple, with no distinction made between the national army and the civilian population, and it is inevitable that the poor Red Cross is drowning in the flood. Sidney H. Brown, ICRC delegate, 25 March 19361 M"e Odier: (...) How can we reconcile the obligation to remain silent with the dictates of human conscience? That is the problem. President: We kept silent because we did not know the truth. Minutes of ICRC meeting, 3 July 19362 Rainer Baudendistel has a degree in philosophy and history from the University of Geneva and an M.A. in international relations from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. An experienced ICRC delegate, the author has spent a total of six years in Ethiopia and Eritrea. 1 "lln'y a plus de possibility de "caritas inter arma", c'est la guerre a outrance pure et simple, sans distinction aucune entre I 'armee nationale et la population civile, et quant a lapauvre Croix-Rouge, il est Men naturel qu'elle soit engloutie dans lesflots. " Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva (hereafter "ICRC Archives"), Rapports des delegues. No. 13, 25 March 1936. - Note: all translations of original French extracts from ICRC Archives by the author. 2 "M"e Odier: (...) Comment concilier le devoir du silence et celui d'exprimer les avis de la conscience humaine? Tel est le probleme. -

Morris Dissertation

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jennifer M. Morris Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________ Judith P. Zinsser, Director ______________________________ Mary Frederickson, Reader _______________________________ David Fahey, Reader _______________________________ Laura Neack, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT THE ORIGINS OF UNICEF, 1946-1953 by Jennifer M. Morris In December, 1946, the United Nations General Assembly voted to approve an International Children’s Emergency Fund that would provide relief assistance to children and their mothers whose lives had been disrupted by World War II in Europe and China. Begun as a temporary operation meant to last only until 1950, the organization, which later became the United Nations Children’s Fund, or UNICEF, went far beyond its original mandate and established programs throughout the world. Because it had become an indispensable provider of basic needs to disadvantaged children and mothers, it lobbied for and received approval from the General Assembly to become a permanent UN agency in 1953. The story of UNICEF’s founding and quest for permanent status reveals much about the postwar world. As a relief organization, it struggled with where, how, and to whom to provide aid. As an international body, it wrestled with the debates that ensued as a result of Cold War politics. Its status as an apolitical philanthropic organization provides a unique perspective from which to forge links between the political, economic and social histories of the postwar period. THE ORIGINS OF UNICEF, 1946-1953 A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History by Jennifer M. -

International Review of the Red Cross, July 1961, First Year

INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS Geneva LEOPOLD BOISSIER, Doctor of Laws, Honorary Professor at the University of Geneva, former Secretary-General to the Inter-Parliamentary Union, President (1946) 1 JACQUES CHENEVIERE, Hon. Doctor of Literature, Honorary Vice-President (1919) LUCIE ODIER, Former Director of the District Nursing Service, Geneva Branch of the Swiss Red Cross (1930) CARL J. BURCKHARDT, Doc~or of Philosophy, former Swiss Minister to France (1933) MARTIN BODMER, Hon. Doctor of Philosophy, Vice-President (1940) ERNEST GLOOR, Doctor of Medicine, Vice-President (1945) PAUL RUEGGER, former Swiss Minister to Italy and the United Kingdom, Member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (1948), on leave RODOLFO OLGIATI, Hon. Doctor of Medicine, former Director of the Don Suisse (1949) MARGUERITE VAN BERCHEM, former Head of Section, Central Prisoners of War Agency (1951) FREDERIC SIORDET, Lawyer, Counsellor of the International Committee of the Red Cross from 1943 to 1951 (1951) GUILLAUME BORDIER, Certificated Engineer E.P.F., M.B.A. Harvard, Banker (1955) ADOLPHE FRANCESCHETTI, Doctor of Medicine, Professor of clinical ophthalmology at Geneva University (1958) HANS BACHMANN, Doctor of Laws, Assistant Secretary-General to the International Committee of the Red Cross from 1944 to 1946 (1958) JACQUES FREYMOND, Doctor of Literature, Director of the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Professor at the University of Geneva (1959) DIETRICH SCHINDLER, Doctor of Laws (1961) SAMUEL GONARD, Colonel Commandant of an Army Corps, former Professor at the Federal Polytechnical School (1961) HANS MEULI, Doctor of Medicine, Brigade Colonel, former Director of the Swiss Army Medical Service (1961) Direction: ROGER GALLOPIN, Doctor of Laws, Executive Director JEAN S. -

The Human Cost of Nuclear Weapons

The human cost Autumn 2015 97 Number 899 Volume of nuclear weapons Volume 97 Number 899 Autumn 2015 Volume 97 Number 899 Autumn 2015 Editorial: A price too high: Rethinking nuclear weapons in light of their human cost Vincent Bernard, Editor-in-Chief After the atomic bomb: Hibakusha tell their stories Masao Tomonaga, Sadao Yamamoto and Yoshiro Yamawaki The view from under the mushroom cloud: The Chugoku Shimbun newspaper and the Hiroshima Peace Media Center Tomomitsu Miyazaki Photo gallery: Ground zero Nagasaki Akitoshi Nakamura Discussion: Seventy years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Reflections on the consequences of nuclear detonation Tadateru Konoé and Peter Maurer Nuclear arsenals: Current developments, trends and capabilities Hans M. Kristensen and Matthew G. McKinzie Pursuing “effective measures” relating to nuclear disarmament: Ways of making a legal obligation a reality Treasa Dunworth The human costs and legal consequences of nuclear weapons under international humanitarian law Louis Maresca and Eleanor Mitchell Chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear events: The humanitarian response framework of the International Committee of the Red Cross Gregor Malich, Robin Coupland, Steve Donnelly and Johnny Nehme Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action The use of nuclear weapons and human rights The human cost of nuclear weapons Stuart Casey-Maslen The development of the international initiative on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons and its effect on the nuclear weapons debate Alexander Kmentt Changing the discourse on nuclear weapons: The humanitarian initiative Elizabeth Minor Protecting humanity from the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons: Reframing the debate towards the humanitarian impact Richard Slade, Robert Tickner and Phoebe Wynn-Pope An African contribution to the nuclear weapons debate Sarah J. -

Marcel Junod, a Former Vice-President of the ICRC, Who Died in 1961

The Hiroshima disaster The text which we print here, entitled "The Hiroshima disaster", was found recently among the papers left by Dr. Marcel Junod, a former Vice-President of the ICRC, who died in 1961. As far as we know, the text has never before been published, though Dr. Junod probably drew on it when writing the last part of his book "Le troisieme combattant" (translated into English as "Warrior without Weapons"). Dr. Junod, an ICRC delegate in the Far East at the end of the Second World War, was the first foreign doctor to visit the ruins of Hiroshima after the atomic explosion and to treat some of the victims. His account, apparently written soon after the event, is therefore a valuable first-hand testimony. Since then, much has been written about Hiroshima and about the atom bomb, possibly better documented, more carefully considered, more elegantly composed. But nothing has better described, in its simple way, the horror of the situation as Dr. Junod saw it. The personality of the author stamps this text, which we now publish almost forty years after he wrote it. His account has lost none of its force, and vividly conveys the shock, and also the fears for the future which Dr. Junod felt as he looked upon the devastation suffered by Hiroshima. 265 http://journals.cambridge.org Downloaded: 29 Jul 2015 IP address: 80.94.146.52 The Hiroshima disaster by Marcel Junod Introduction Hiroshima, 6 August 1945—Dawn of the atomic age. A Japanese city with 400,000 inhabitants is annihilated in a few seconds. -

2011 Nuclear Weapons

iinternationalnternational hhumanitarianumanitarian llawaw magazine IssueIssue 2, 2 2011 nnuclearuclear wweaponseapons: a uuniquenique tthreathreat ttoo hhumanityumanit y Inside this issue Editorial status of the world’s nuclear arsenal This edition of our international humanitarian law magazine – by Tim Wright, Australian director, focuses on the most dangerous weapons of all: nuclear International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear weapons. The disastrous effects of nuclear weapons were made Weapons (ICAN) – page 3 violently clear during the fi nal stages of the Second World War, the legal framework regulating when two atomic bombs were deployed against the cities of nuclear weapons – by John Carlson, Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Since that time there has been an Visiting Fellow at the Lowy Institute, and alarming proliferation of these weapons and today they remain a counsellor to the Washington-based Nuclear uniquely destructive threat to all of humanity and the environment. Threat Initiative (NTI) on non-proliferation, The Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement has been at the disarmament and verifi cation issues centre of the nuclear weapons debate from the very outset. From – page 4 1945 to 2011, the Movement has consistently voiced its deep nuclear war - the environmental concerns about these weapons of mass destruction and the impacts – by Ira Helfand, emergency need for the prohibition of their use. Red Cross’ role in developing physician and past president of Physicians IHL led to the creation of the Additional Protocols to the Geneva for Social Responsibility – page 7 Conventions in 1977. Key provisions of the Additional Protocols reaffi rm and strengthen the IHL principles of distinction between nuclear weapons: a threat to combatants and civilians, and that no unnecessary suffering survival and health – by Tilman Ruff, is caused in times of war. -

Gallery2017 Hiroshima.Pdf

Why Was Hiroshima Chosen as a Target? ࠙ Opportunity for Hiroshima to be Bombed ࠚ In order to deliver a final and decisive blow against Japan, the United States began developing the first atomic bomb. The atomic bomb was produced by the Manhattan Project, and experimentation on the atomic bomb began in 1942 and concluded with a full-scale test on July 16th, 1945. It was the first atomic bomb in the world. ࠙ Consideration of the Drop Target ࠚ A target consideration committee that consisted of military personnel and scientists selected target cities and decided 17 potential areas on April 27th, 1945. After that, the selection of targets were narrowed down based on those that could be damaged due to the blast and so on. Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and Kokura were selected as potential targets in the 2nd meeting on May 11th. ࠙ The Approval of Using an Atomic Bomb ࠚ Approval of the final target was taken by President Truman. A temporary committee was organized in May 1945. At a meeting in June, it was decided that the use of the atomic bomb should progress; however, some scientists who developed the bomb were against it. ࠙ Dropping of Mock Bombs ࠚ The atomic bomb is different from other bombs in that its drop method is different. Training was conducted in the desert in America to perfect the method. America dropped mock bombs on the area surrounding the target cities from July to August 1945. ࠙ Selecting Hiroshima ࠚ The command to drop the atomic bomb was issued on July 25th, 1945. -

International Review of the Red Cross, September-October 1982

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER1~2 TWENTY· SECOND YEAR - No. 230 international review• of the red cross PROPERTY OF U.S. t.":'.MY THE JUDGE ADVOChTL:: GENERAL'S SCHOOL INTER ARMA CARITAS UBRARY GENEVA INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS FOUNDED IN 1863 INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS Mr. ALEXANDRE HAY, Lawyer, former Director-General of the Swiss National Bank. President (member since 1975) Mr. HARALD HUBER, Doctor of Laws, Federal Court Judge, Vice-President (1969) Mr. RICHARD PESTALOZZI, Doctor of Laws, Vice-President (1977) Mr. JEAN PICTET. Doctor of Laws, former Vice-President of the ICRC (1967) Mrs. DENISE BINDSCHEDLER-ROBERT. Doctor of Laws, Professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva. Judge at the European Court of Human Rights (1967) Mr. MARCEL A. NAVILLE. Master of Arts. ICRC President from 1969 to 1973 (1967) Mr. JACQUES Po DE ROUGEMONT, Doctor of Medicine (1967) Mr. VICTOR H. UMBRICHT, Doctor of Laws. Managing Director (1970) Mr. GILBERT ETIENNE, Professor at the Graduate Institute of International Studies and at the Institut d'6tudes du d6veloppement, Geneva (1973) Mr. ULRICH MIDDENDORP, Doctor of Medicine, head of surgical department of the Cantonal Hospital, Winterthur (1973) Mrs. MARION BOvEE-ROTHENBACH. Doctor of Sociology (1973) Mr. HANS PETER TSCHUDI, Doctor of Laws, former Swiss Federal Councillor (1973) Mr. HENRY HUGUENIN. Banker (1974) Mr. JAKOB BURCKHARDT. Doctor of Laws. Minister Plenipotentiary (1975) Mr. THOMAS FLEINER. Master of Laws, Professor at the University of Fribourg (1975) Mr. ATHOS GALLINO, Doctor of Medicine, Mayor of Bellinzona (1977) Mr. ROBERT KOHLER, Master of Economics (1977) Mr. MAURICE AUBERT, Doctor of Laws.