The Nagasaki Disaster and the Initial Medical Relief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Nagasaki. an European Artistic City in Early Modern Japan

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal Curvelo, Alexandra Nagasaki. An European artistic city in early modern Japan Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, núm. 2, june, 2001, pp. 23 - 35 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36100202 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2001, 2, 23 - 35 NAGASAKI An European artistic city in early modern Japan Alexandra Curvelo Portuguese Institute for Conservation and Restoration In 1569 Gaspar Vilela was invited by one of Ômura Sumitada’s Christian vassals to visit him in a fishing village located on the coast of Hizen. After converting the lord’s retainers and burning the Buddhist temple, Vilela built a Christian church under the invocation of “Todos os Santos” (All Saints). This temple was erected near Bernardo Nagasaki Jinzaemon Sumikage’s residence, whose castle was set upon a promontory on the foot of which laid Nagasaki (literal translation of “long cape”)1. If by this time the Great Ship from Macao was frequenting the nearby harbours of Shiki and Fukuda, it seems plausible that since the late 1560’s Nagasaki was already thought as a commercial centre by the Portuguese due to local political instability. Nagasaki’s foundation dates from 1571, the exact year in which the Great Ship under the Captain-Major Tristão Vaz da Veiga sailed there for the first time. -

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War TACHIKAWA Kyoichi Abstract Why does the inhumane treatment of prisoners of war occur? What are the fundamental causes of this problem? In this article, the author looks at the principal examples of abuse inflicted on European and American prisoners by military and civilian personnel of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy during the Pacific War to analyze the causes of abusive treatment of prisoners of war. In doing so, the author does not stop at simply attributing the causes to the perpetrators or to the prevailing condi- tions at the time, such as Japan’s deteriorating position in the war, but delves deeper into the issue of the abuse of prisoners of war as what he sees as a pathology that can occur at any time in military organizations. With this understanding, he attempts to examine the phenomenon from organizational and systemic viewpoints as well as from psychological and leadership perspectives. Introduction With the establishment of the Law Concerning the Treatment of Prisoners in the Event of Military Attacks or Imminent Ones (Law No. 117, 2004) on June 14, 2004, somewhat stringent procedures were finally established in Japan for the humane treatment of prisoners of war in the context of a system infrastructure. Yet a look at the world today shows that abusive treatment of prisoners of war persists. Indeed, the heinous abuse which took place at the former Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War is still fresh in our memories. -

FY20.3 Annual Investors Meeting

FY20.3 Annual Investors Meeting May 12, 2020 Kyushu Railway Company Contents Highlights 3 Ⅰ Financial results for FY20.3 4 Ⅱ Forecasts for FY21.3 11 Ⅲ Short-term strategies 15 Ⅳ Status of Medium-Term Business Plan Initiatives 18 APPENDIX 28 2 Highlights Results Consolidated operating revenue, operating income, ordinary income, and net for FY20.3 income all declined. Due to the influence of the spread of the COVID 19 infection, future revenue trends Forecasts are very unclear, and accordingly our results forecast and annual dividends have not for FY21.3 yet been determined at this point. In the future, when it becomes possible to make a forecast, we will release it promptly. Cash flow is declining substantially, centered on the decline in railway passenger revenues. Accordingly, we will advance measures with the highest priority on securing liquidity at hand. In preparation for further worsening of cash flow, we will consider and implement Short-term diversification of our fund-raising methods. strategies Looking at capital investment, we will steadily advance railway safety investment and investment in two station buildings. On the other hand, we will delay or control investment as much as possible. When we generate cash through the reevaluation of our portfolio, we will first allocate it to working capital. Status of To further strengthen our management foundation, we will accelerate the reevaluation Medium-Term of our business portfolio. Business Plan We will work to build sustainable railway services through improved profitability, and will strive to increase the population in the areas around our railway lines by investing Initiatives in strategic city-building initiatives in the regions around our bases. -

Spectrum of the Seas®

Spectrum of the Seas® One of the most innovative ships in the world, Spectrum of the Seas® heads east again in 2021 to deliver unforgettable immersive adventures to Japan and Vietnam. Sail from Shanghai starting January 2021 on 4 to 7 night itineraries to iconic Japanese ports like cosmopolitan Kobe, laid-back Fukuoka, and neon-lit Tokyo. Or sail from Hong Kong in December on 4-5 night sailings to tropical Okinawa and Ishigaki in Japan, or to the enchanting cities of Da Nang or Hue in Vietnam. And from May to October in 2021, Voyager of the Seas® makes its way to Beijing to offer 4-7 night itineraries with stops at culture- rich Kyoto and vibrant Nagasaki. ITINERARY SAIL DATE PORT OF CALL 8-Night Best of Chan May January 2, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Cruising (2 Nights) • Fukuoka, Japan • Kagoshima, Japan • Nagasaki, Japan • Cruising (2 Nights) • Hong Kong, China 5-Night Okinawa Overnight January 10, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Cruising • Okinawa, Japan (Overnight) • Cruising • Hong Kong, China 5-Night Best of Taiwan January 15, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Kaohsiung, Taiwan, China • Taichung, Taiwan, China • Taipei (Keelung), Taiwan, China • Cruising • Hong Kong, China 4-Night Best of Okinawa January 20, 2021 Hong Kong, China • Cruising • Okinawa, Japan • Cruising • Shanghai (Baoshan), China 5-Night Okinawa & January 24, 2021 Shanghai (Baoshan), China • Cruising • Okinawa, Kagoshima Japan • Kagoshima, Japan • Cruising • Shanghai (Baoshan), China Book your Asia adventures today! Features vary by ship. All itineraries are subject to change without -

Board of Porei^I} ^Issiops

■ . ^ UNIVE% > ■ D A Y M iS S IO N S \ / / f? R £ R ^ The Scvcnty-Sccond Annual Report— ^ OF THE Board of porei^i} ^issiops OF THE REFORMED CHURCH IN AMERICA AND FORTY-SEVENTH OF SEPARATE ACTION With the Treasurer’s Tabular and Summary Reports Receipts for the year ending April 30, 1904 BOARD OF PUBLICATION OF THE REFORMED CHURCH IN AMERICA 25 EAST 22d STREET NEW YORK PRESS OF HE UNIONIST-GAZETTE ASSOCIATION. SOMERVILLE, N. J. REPORT. The Board of Foreign Missions presents to the General Synod its Seventy-second Annual Report, (the forty-seventh of separate and independent action), with mingled satisfaction and regret. It is happy to report, for the third time in succession, the clos ing of the fiscal year without debt. It also rejoices and congratu lates the Synod and the Church that, while the lives of all our be loved missionaries have been preserved, the Board has been able to put into the field more missionaries than in any single year for a long time past. Three ordained men and six women have been sent out from this country and two women added on the field, one in China and one in Arabia. There were thus eleven additions made to the force, all greatly needed and cordially welcomed by the Missions to whom they were added. On the other hand, the receipts for the work of these Missions, under the regular appropriations of the Board, show a decided falling off from last year, and are less than for any year since 1900. They fall $25,000 short of the $135,000 proposed by the last Synod, as the lowest estimate of what should be raised for the foreign work of the Church during the year. -

The International Committee of the Red Cross

The Ethical Witness: The International Committee of the Red Cross Ritu Mathur Ph.D Student Department of Political Science York University YCISS Working Paper Number 47 February 2008 The YCISS Working Paper Series is designed to stimulate feedback from other experts in the field. The series explores topical themes that reflect work being undertaken at the Centre. How are we to understand the ethics of humanitarian organizations as they act as witnesses to situations of armed conflict? How do the ethics of a humanitarian organization influence its silence or speech with regard to particular situations of armed conflict? How is this silence or speech interpreted as a moral failure or a moral success of a humanitarian organization? These questions are central to my concern with the ethics and politics of humanitarianism. These questions have relevance to undertakings of humanitarian organizations in a historical sense during the period of the Second World War to the present day conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. I am interested in exploring these questions by presenting a close study of ethics as articulated by Giorgio Agamben in his book Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive.1 I am particularly interested in his concept of the witness as an ethical entity charting the topography of political violence. By positing the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) as a witness to the holocaust, I am interested in observing how Agamben’s perspective on ethics provides new insights into understanding the ethics of a humanitarian organization and how it is important for a thinker’s engagement with ethics to be grounded in an empirical reality experienced by humanitarian actors. -

Shinkansen - Wikipedia 7/3/20, 10�48 AM

Shinkansen - Wikipedia 7/3/20, 10)48 AM Shinkansen The Shinkansen (Japanese: 新幹線, pronounced [ɕiŋkaꜜɰ̃ seɴ], lit. ''new trunk line''), colloquially known in English as the bullet train, is a network of high-speed railway lines in Japan. Initially, it was built to connect distant Japanese regions with Tokyo, the capital, in order to aid economic growth and development. Beyond long-distance travel, some sections around the largest metropolitan areas are used as a commuter rail network.[1][2] It is operated by five Japan Railways Group companies. A lineup of JR East Shinkansen trains in October Over the Shinkansen's 50-plus year history, carrying 2012 over 10 billion passengers, there has been not a single passenger fatality or injury due to train accidents.[3] Starting with the Tōkaidō Shinkansen (515.4 km, 320.3 mi) in 1964,[4] the network has expanded to currently consist of 2,764.6 km (1,717.8 mi) of lines with maximum speeds of 240–320 km/h (150– 200 mph), 283.5 km (176.2 mi) of Mini-Shinkansen lines with a maximum speed of 130 km/h (80 mph), and 10.3 km (6.4 mi) of spur lines with Shinkansen services.[5] The network presently links most major A lineup of JR West Shinkansen trains in October cities on the islands of Honshu and Kyushu, and 2008 Hakodate on northern island of Hokkaido, with an extension to Sapporo under construction and scheduled to commence in March 2031.[6] The maximum operating speed is 320 km/h (200 mph) (on a 387.5 km section of the Tōhoku Shinkansen).[7] Test runs have reached 443 km/h (275 mph) for conventional rail in 1996, and up to a world record 603 km/h (375 mph) for SCMaglev trains in April 2015.[8] The original Tōkaidō Shinkansen, connecting Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka, three of Japan's largest cities, is one of the world's busiest high-speed rail lines. -

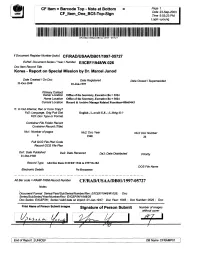

CF Item = Barcode Top - Note at Bottom = Page 1 CF Ltem One BC5-Top-Sign Date 23-Sep-2003 Time 5:03:23 PM Login Uyoung

CF Item = Barcode Top - Note at Bottom = Page 1 CF_ltem_One_BC5-Top-Sign Date 23-Sep-2003 Time 5:03:23 PM Login uyoung CF/RAD/USAA/DBOl/1997-05727 II Document Register Number [auto] CF/RAD/USAA/DB01/1997-05727 ExRef: Document Series / Year/ Number E/ICEF/1948/W.026 Doc Item Record Title Korea - Report on Special Mission by Dr. Marcel Junod Date Created/On Doc Date Registered Date Closed / Superseeded 21-Oct-1948 OWan-1997 Primary Contact Owner Location Office of the Secretary, Executive Bo = 3024 Home Location Office of the Secretary, Executive Bo = 3024 Current Location Record & Archive Manage Related Functions=80669443 11: In Out Internal, Rec or Conv Copy? Fd2: Language, Orig Pub Dist English, L.Avail: E,f..; L.Orig: E-? Fd3: Doc Type or Format Container File Folder Record Container Record (Title) Nu1: Number of pages Nu2: Doc Year Nu3: Doc Number 0 1948 26 Full GCG File Plan Code Record GCG File Plan Da1: Date Published Da2: Date Received Da3: Date Distributed Priority 21-0ct-1948 Record Type A04 Doc Item: E/ICEF1946 to 1997 Ex Bd DOS File Name Electronic Details No Document Alt Bar code = RAMP-TRIM Record Number CF/RAD/USAA/DB01/1997-05727 Notes Document Format Series/Year/SubSeries/Number/Rev: E/ICEF/1948/W.026; Doc Series/SubSeries/Year/Number/Rev:E/ICEF/W/1948/26 Doc Series: E/ICEF/W; Series Valid date on import: 01-Jan-1947; Doc Year: 1948; Doc Number: 0026; Doc Print Name of Person Submit Images Signature of Person Submit Number of images without cover iy>*L> «-*. -

Rail Pass Guide Book(English)

JR KYUSHU RAIL PASS Sanyo-San’in-Northern Kyushu Pass JR KYUSHU TRAINS Details of trains Saga 佐賀県 Fukuoka 福岡県 u Rail Pass Holder B u Rail Pass Holder B Types and Prices Type and Price 7-day Pass: (Purchasing within Japan : ¥25,000) yush enef yush enef ¥23,000 Town of History and Hot Springs! JR K its Hokkaido Town of Gourmet cuisine and JR K its *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. Where is "KYUSHU"? All Kyushu Area Northern Kyushu Area Southern Kyushu Area FUTABA shopping! JR Hakata City Validity Price Validity Price Validity Price International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor 36+3 (Sanjyu-Roku plus San) Purchasing Prerequisite visa may purchase the pass. 3-day Pass ¥ 16,000 3-day Pass ¥ 9,500 3-day Pass ¥ 8,000 5-day Pass Accessible Areas The latest sightseeing train that started up in 2020! ¥ 18,500 JAPAN 5-day Pass *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. This train takes you to 7 prefectures in Kyushu along ute Map Shimonoseki 7-day Pass ¥ 11,000 *Children under the age of 5 are free. However, when using a reserved seat, Ro ¥ 20,000 children under five will require a Children's JR Kyushu Rail Pass or ticket. 5 different routes for each day of the week. hu Wakamatsu us Mojiko y Kyoto Tokyo Hiroshima * All seats are Green Car seats (advance reservation required) K With many benefits at each International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor R Kyushu Purchasing Prerequisite * You can board with the JR Kyushu Rail Pass Gift of tabi socks for customers J ⑩ Kokura Osaka shops of JR Hakata city visa may purchase the pass. -

Remains of Hinoe Castle Shimabara Ekimae Hinoe Castle ・Time: 20Min

〔as of October, 2019〕 〔Tourism contact〕 Minamishimabara Himawari Tourism Association TEL: 0957-65-6333 Isahaya Shimabara Station Nagasaki address: Bo, Kitaarima-cho, Minamishimabara City, Nagasaki Pref. ■Get on a bus bound for Shimabara Port Remains of Hinoe Castle Shimabara Ekimae Hinoe Castle ・time: 20min. ・fare: 490yen ・Shimatetsu Bus: 0957-86-3179 Kazusa Hara Castle ・15min. ・15min. Kuchinotsu walk walk *nearest bus stop is ‘Hashiguchi’ Oniike Port ■ferry ・time: 30min. ‘Hashiguchi’ or ‘Hinoe-jo Iriguchi’ ‘Hinoe-jo Iriguchi’ (Amakusa City) ・fare: 360yen ・15round services per day Shimate ’ - ・ Kumamoto Port or ‘Tabira Bus tsu ferry Shimatetsu Kankou: ■Get on a bus bound for 0957-62-2447 Shimate - Shimate - tsu Bus tsu ■ tsu Bus tsu Get on a bus bound for Arie ■Kumamoto Ferry Kazusa beach ・ ・time: 1h35min. ・fare: 1,550yen ・3 buses per day ・time: 30min. time: 50min. ・ ・ ferry Shimatetsu Bus (Isahaya branch):0957-22-4091 ・fare: 1,100yen (single) fare: 800yen Kuchinotsu Port or bus stop ・contact: 0957-63-8008 *If the bus goes on a national route, get off at Hiinoe-jo ■Get on a bus bound for Kazusa beach ■Get on a bus bound for Shimatetsu Bus ■Kyusho Ferry Iriguchi. (fare: 850yen) ・time: 1h ・fare: 880yen Kuchinotsu ・ ・time: 60min. Shimatetsu Bus: 0957-62-4707 *If the bus goes on a national route, get off at Hiinoe-jo Iriguchi. (fare: 910yen) ・time: 1h30min. ・fare: 1,650yen ・fare: 890yen (single) Shimatetsu ・contact: 0957-62-3246 Bus Shimabara Station (Shimatetsu or Bus) Shimabara Port ‘Shimabara- ■bus (from Hakata Bus Terminal to Shimabara Shimabara Shimate - (Gaikou) kou’ Ekimae) express way Shimate bus: ■ Railway tsu Bus tsu Shimabara Railway (from Isahaya ■Get on a bus or Nishitetsu Bus Bus tsu Station to Shimabara Station ) ・time: 3h 20min (Reservation required) bound for Shi- ・ ・time: 1h 15min. -

A Doctor's Account

THE HIROSHIMA DISASTER - A DOCTOR'S ACCOUNT Marcel Junod was the first foreign doctor to reach Hiroshima after the atom bomb attack on 6 August 1945. Junod, the new head of the ICRC's delegation in Japan, arrived in Tokyo on 9 August 1945 - the very day that the United States dropped a second atomic bomb, this time on Nagasaki. Junod, who had been travelling for two months and had not caught up with the news, was astounded: “For the first time I heard the name of Hiroshima, the words "atom bomb". Some said that there were possibly 100,000 dead; others retorted 50,000. The bomb was said to have been dropped by parachute, the victims had been burnt to death by rays, etc...” Information was hard to come by, and Junod's immediate task was to visit Allied prisoners of war held in Japan (Emperor Hirohito's surrender broadcast came on 15 August). It was only after one of the ICRC delegates in the field sent Junod a telegram with apocalyptic details of the Hiroshima disaster that Junod could set the wheels in motion for a belated, but still vital, relief effort. On 8 September he flew from Tokyo with members of an American technical commission, and a consignment of relief provided by the US armed forces. “At twelve o'clock, we flew over Hiroshima. We... witnessed a site totally unlike anything we had ever seen before. The centre of the city was a sort of white patch, flattened and smooth like the palm of a hand. Nothing remained. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13