Morris Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cr-Pr-Bio-Pate-1970

CF Item = Barcode Top - Note at Bottom = Page 1 : CF_ltem_One_BC5-Top-Sign Date 31-Mar-20I04I Time 12:43:43 P3 Ml Login uyoung CF/RAI/USAA/DB01/HS/2004-00128 Full Item Register Number [auto] CF/RAI/USAA/DB01 /HS/2004-00128 ExRef: Document Series/Year/Number Record Item Title UNICEF Press Release No. 70/73, Biographical Note for information media, not an official record Maurice Pate: Executive Director, UNICEF 1946-1965 Date Created /on Item Date Registered Date Closed/Superceeded 31-Mar-2004 31-Mar-2004 Primary Contact Owner Location Record & Archive Manage Related Functions=80669443 Home Location History Related Records =60909132 Current Location Record & Archive Manage Related Functions=80669443 Fd1: Type: IN, OUT, INTERNAL? Fd2: Lang ?Sender Refer Cross Re/ F3: Format Container Record Container Record (Title) N1: Numb of pages N2: Doc Year A/3: Doc Number 0 0 0 Full GCG Code Plan Number Da 1 .-Date Published Da2:Date Received Date3 Priority If Doc Series?: Record Type A02 Hist Corr Item DOS File Name Electronic Details No Document Alt Bar code = RAMP-TRIM Record Numb: CF/RAI/USAA/DB01/HS/2004-00128 Notes Print Name of Person Submit Images Signature of Person Submit Number of images without cover c/^ i i ^7r v | 1 "^ i * i l-^e-'iJL^u. -T—*- ^ fj End of Report ][|JNICEF DB Name CFRAMP01 ] (For use of information media - Not an official record) PRESS RELEASE, No. 70/37 • " 30 April 1971 Biographical Note Maurice Pate ^ Executive Director, UNICEF. 1946 - 196? * • Maurice Pate was born on 14 October 1894 in Ponder, Nebraska and. -

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War

The Treatment of Prisoners of War by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy Focusing on the Pacific War TACHIKAWA Kyoichi Abstract Why does the inhumane treatment of prisoners of war occur? What are the fundamental causes of this problem? In this article, the author looks at the principal examples of abuse inflicted on European and American prisoners by military and civilian personnel of the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy during the Pacific War to analyze the causes of abusive treatment of prisoners of war. In doing so, the author does not stop at simply attributing the causes to the perpetrators or to the prevailing condi- tions at the time, such as Japan’s deteriorating position in the war, but delves deeper into the issue of the abuse of prisoners of war as what he sees as a pathology that can occur at any time in military organizations. With this understanding, he attempts to examine the phenomenon from organizational and systemic viewpoints as well as from psychological and leadership perspectives. Introduction With the establishment of the Law Concerning the Treatment of Prisoners in the Event of Military Attacks or Imminent Ones (Law No. 117, 2004) on June 14, 2004, somewhat stringent procedures were finally established in Japan for the humane treatment of prisoners of war in the context of a system infrastructure. Yet a look at the world today shows that abusive treatment of prisoners of war persists. Indeed, the heinous abuse which took place at the former Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War is still fresh in our memories. -

1391St Meeting ECONOMIC and SOCIAL COUNCIL Monday, 26 July 1965 Thirty-Ninth Session At' 3.20 P.M

UNITED NATIONS 1391st meeting ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL Monday, 26 July 1965 Thirty-ninth session at' 3.20 p.m. OFFICIAL RECORDS PALAIS DES NATIONS, GENEVA CONTENTS 2. Mr. BOUATTOURA (Algeria) aaid that, after con.. Page sultation with other delegations, the sponsors wished Agenda item 24: to :make two amendments to the draft. The third pre Report of the Secretary-General on the United Nations ambular paragraph should be altered to read " Noting Institute for Training aud Research (concluded) • • • • 209 with interest the progress made so far in establishing Agenda item 30: the Institute ", and in operative paragraph 4, the words Report of the Executive Board of the United Nations Child- " to provide the Economic and Social Council at the ren's Fund . • . • • , . • • • . • 209 resumed thirty-ninth session with any additional informa Agenda item 25: tion and " should be inserted after " Secretary-General ". Report of the Commission on Human Rights 3. Mr. MORA BOWEN (Ecuador) said that, in order Report of the Social Committee . • • • . • 216 to make it clear which governments were referred to in Joint draft resolution . • . • . • . • . • • • . 216 operative paragraph 3, the opening words of the paragraph should be amended to read " Renews its appeal to the Governments of State.s Members of the United Nations, President: Mr. A. MATSUI (Japan) of the specialized agencies and of the International Atomic Energy Agency and to private institutions ..• ". That Present: amendment was acceptable to all the sponsors. Representatives of the following -

From Cow Pasture to Executive Airport

From Cow Pasture to Executive Airport Theresa L. Kraus, FAA Historian The early twentieth century witnessed myriad aviation developments as new planes and technologies entered service and early pilots, male and female, pushed one another to set, and then break, a host of aviation records for speed, flight duration, and aerobatics. During World War I, the airplane had proved its effectiveness as a military tool and, with the advent of early airmail service, congressionally authorized in 1918, and it showed great promise for commercial applications. Despite limited postwar technical developments, however, early aviation remained a dangerous business — the realm of daredevils. Flying conditions proved difficult since the only navigation devices available to most pilots were magnetic compasses. They flew 200 to 500 feet above ground so they could navigate by roads and railways. Low visibility and night landings were made using bonfires on the field as lighting. Fatal accidents were routine. It was during this era of barnstorming and flying circuses that the Town of Leesburg, Virginia, caught the aviation bug. In 1918, a wayward pilot landed his plane in a pasture on Wallace George’s farm. George’s farm house, located at 229 Edward’s Ferry Road, was on the south side of Edward’s Ferry Road, west of Route 15. The pilot, no doubt, had been flying along Route 15 when he needed to find a spot to land his craft. Curious townspeople certainly found the sight of an airplane in their neighbor’s pasture a fun curiosity. George’s field soon became a popular landing spot for early barnstormers, and, sometimes, for an airmail plane or two. -

American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 7-21-2014 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas D. Westerman University of Connecticut, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Westerman, Thomas D., "Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 466. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/466 Rough and Ready Relief: American Identity, Humanitarian Experience, and the Commission for Relief in Belgium, 1914-1917 Thomas David Westerman, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2014 This dissertation examines a group of American men who adopted and adapted notions of American power for humanitarian ends in German-occupied Belgium with the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) during World War I. The CRB, led by Herbert Hoover, controlled the importation of relief goods and provided supervision of the Belgian-led relief distribution. The young, college-educated American men who volunteered for this relief work between 1914 and 1917 constructed an effective and efficient humanitarian space for themselves by drawing not only on the power of their neutral American citizenship, but on their collectively understood American-ness as able, active, yet responsible young men serving abroad, thereby developing an alternative tool—the use of humanitarian aid—for the use and projection of American power in the early twentieth century. Drawing on their letters, diaries, recollections as well as their official reports on their work and the situation in Belgium, this dissertation argues that the early twentieth century formation of what we today understand to be non-state, international humanitarianism was partially established by Americans exercising explicit and implicit national power during the years of American neutrality in World War I. -

Federer, Mike Bryan Seek Milestone Wins on Friday

MERCEDES CUP: DAY 5 MEDIA NOTES Friday, June 10, 2016 TC Weissenhof, Stuttgart, Germany | June 6-12, 2016 Draw: S-28, D-16 | Prize Money: €606,525 | Surface: Grass ATP Info Tournament Info ATP PR & Marketing www.ATPWorldTour.com www.mercedescup.de Martin Dagahs: [email protected] @ATPWorldTour @MercedesCup Press Room: +49 711 32095705 facebook.com/ATPWorldTour facebook.com/MercedesCup FEDERER, MIKE BRYAN SEEK MILESTONE WINS ON FRIDAY QUARTER-FINAL PREVIEW: No. 1 seed Roger Federer could pass Hall-of-Famer Ivan Lendl on Friday and move into second place in the Open Era with 1,072 victories. Federer faces Florian Mayer in the Mercedes Cup quarter-finals, and with a win would trail only Jimmy Connors among the winningest players since the spring of 1968. Federer has a 6-0 FedEx ATP Head 2 Head record against Mayer, including straight-set wins on German grass at the Gerry Weber Open in 2005, 2012 and 2015. Federer is not the only man with a milestone on the line in Stuttgart. Mike Bryan seeks his 1,000th doubles win when he and twin brother Bob face Oliver Marach and Fabrice Martin in a semi-final match on Court 1. Only Federer, Lendl, Connors and Daniel Nestor have earned at least 1,000 victories in singles or doubles. Bob Bryan has 985 doubles wins individually. As a team, the Bryans are 984-300. Also in action are a pair of players who won their first ATP World Tour title in Stuttgart: 2002 champion Mikhail Youzhny and 2008 champion Juan Martin del Potro. -

The International Committee of the Red Cross

The Ethical Witness: The International Committee of the Red Cross Ritu Mathur Ph.D Student Department of Political Science York University YCISS Working Paper Number 47 February 2008 The YCISS Working Paper Series is designed to stimulate feedback from other experts in the field. The series explores topical themes that reflect work being undertaken at the Centre. How are we to understand the ethics of humanitarian organizations as they act as witnesses to situations of armed conflict? How do the ethics of a humanitarian organization influence its silence or speech with regard to particular situations of armed conflict? How is this silence or speech interpreted as a moral failure or a moral success of a humanitarian organization? These questions are central to my concern with the ethics and politics of humanitarianism. These questions have relevance to undertakings of humanitarian organizations in a historical sense during the period of the Second World War to the present day conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. I am interested in exploring these questions by presenting a close study of ethics as articulated by Giorgio Agamben in his book Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive.1 I am particularly interested in his concept of the witness as an ethical entity charting the topography of political violence. By positing the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) as a witness to the holocaust, I am interested in observing how Agamben’s perspective on ethics provides new insights into understanding the ethics of a humanitarian organization and how it is important for a thinker’s engagement with ethics to be grounded in an empirical reality experienced by humanitarian actors. -

Annual Report 2010

ANNUAL REPORT 2010 UNICEF_AR_2010_Cover_cc.indd 3 5/18/11 6:21 PM Front cover photo: © UNICEF/NYHQ2010-1636/Ramoneda In August 2010, children cook over an open fi re in Sukkur, a city in Sindh Province. Behind them, a tent camp fi lls the landscape. Their family are staying at the periphery of the camp, which is full and cannot accommodate them, Pakistan. For any corrigenda found subsequent to printing, please visit our website at <www.unicef.org/publications> Note on source information: Data in this report are drawn from the most recent available statistics from UNICEF and other UN agencies, annual reports prepared by UNICEF country offi ces and the June 2011 UNICEF Executive Director’s Annual Report to the Executive Board. Note on resources: All amounts unless otherwise specifi ed are in US dollars. UNICEF_AR_2010_Cover_cc.indd 4 5/13/11 8:12 AM UNICEF ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Covering 1 January 2010 through 31 December 2010 CONTENTS Foreword 2 1 Development with equity 4 2 A healthy foundation 10 3 Education for all 18 4 Equality in protecting children 24 5 Advocacy for action 30 6 Reaching the most vulnerable to crisis 36 7 The business of delivering results 42 Unicef AR_2010_5-11_cc.indd 1 5/13/11 7:57 AM FOREWORD 2010 was a pivotal year for UNICEF, as we began to deepen our traditional focus on reaching the most vulnerable children. The year made the urgency of that renewed focus clear, again and again – most extremely in Haiti and Pakistan. All emergencies and crises put children at greater risk of exploitation and abuse, and disadvantaged children even more so. -

Tournament Notes

TournamenT noTes as of march 31, 2010 THE RIVER HILLS USTA $25,000 WOMEN’S CHALLENGER JACKSON, MS • APRIL 4-11 USTA PRO CIRCUIT RETURNS TO JACKSON FOR 12TH STRAIGHT YEAR TournamenT InFormaTIon The River Hills USTA $25,000 Women’s Challenger is the 10th $25,000 women’s tournament of the year and the only $25,000 Site: River Hills Country Club – Jackson, Miss. women’s event held in Mississippi. Jackson Websites: www.riverhillsclub.net, is the second of three consecutive clay court procircuit.usta.com events on the USTA Pro Circuit in the lead-up to the 2010 French Open. Bryn Lennon/Getty Images Qualifying draw begins: Sunday, April 4 Main draw begins: Tuesday, April 6 This year’s main draw is expected to include Julia Cohen, an All-American at the University Main Draw: 32 Singles / 16 Doubles of Miami who reached the semifinals of the NCAA tournament as a sophomore in 2009, Surface: Clay / Outdoor Lauren Albanese, who won the 2006 USTA Prize Money: $25,000 Girls’ 18s National Championships to earn an automatic wild card into the US Open, and Tournament Director: Kimberly Couts, a frequent competitor on the Dave Randall, (601) 987-4417 USTA Pro Circuit who won the 2006 Easter Lauren Albanese won the 2006 USTA Girls’ [email protected] Bowl as a junior and was a former USTA Girls’ 18s National Championships to earn an 16s No. 1. automatic wild card into the US Open. Tournament Press Contact: Kendall Poole, (601) 987-4454 International players in the main draw include freshman in 2009 and led Duke University [email protected] -

Executive Board of the United Nations Children's Fund

E/2006/34/Rev.1-E/ICEF/2006/5/Rev.1 United Nations Executive Board of the United Nations Children’s Fund Report on the first, second and annual sessions of 2006 Economic and Social Council Official Records, 2006 Supplement No. 14 Economic and Social Council Official Records, 2006 Supplement No. 14 Executive Board of the United Nations Children’s Fund Report on the first, second and annual sessions of 2006 United Nations • New York, 2006 E/2006/34/Rev.1 E/ICEF/2006/5/Rev.1 Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. ISSN 0252-3507 Contents Paragraphs Page Part one First regular session of 2006 1 I. Organization of the session 1 – 7 2 A. Election of officers 1 2 B. Opening statements 2 – 5 2 C. Adoption of the agenda 6 – 7 3 II. Deliberations of the Executive Board 8 – 129 3 A. Annual report of the Executive Director to the Economic and Social Council 8 – 21 3 B. Approval of revised country programme documents 22 – 25 5 C. Biennial support budget for 2006-2007 26 – 38 6 D. Intercountry programmes 39 – 42 8 E. Report on thematic funding in support of the medium-term strategic plan 43 – 44 8 F. UNICEF health and nutrition strategy 45 – 52 9 G. UNICEF humanitarian response to recent crises: oral report 53 – 78 10 H. UNICEF water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) strategy 79 – 89 13 I. UNICEF education strategy: oral report 90 – 103 14 J. Private Sector Division work plan and proposed budget for 2006 104 – 109 16 K. -

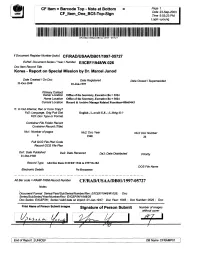

CF Item = Barcode Top - Note at Bottom = Page 1 CF Ltem One BC5-Top-Sign Date 23-Sep-2003 Time 5:03:23 PM Login Uyoung

CF Item = Barcode Top - Note at Bottom = Page 1 CF_ltem_One_BC5-Top-Sign Date 23-Sep-2003 Time 5:03:23 PM Login uyoung CF/RAD/USAA/DBOl/1997-05727 II Document Register Number [auto] CF/RAD/USAA/DB01/1997-05727 ExRef: Document Series / Year/ Number E/ICEF/1948/W.026 Doc Item Record Title Korea - Report on Special Mission by Dr. Marcel Junod Date Created/On Doc Date Registered Date Closed / Superseeded 21-Oct-1948 OWan-1997 Primary Contact Owner Location Office of the Secretary, Executive Bo = 3024 Home Location Office of the Secretary, Executive Bo = 3024 Current Location Record & Archive Manage Related Functions=80669443 11: In Out Internal, Rec or Conv Copy? Fd2: Language, Orig Pub Dist English, L.Avail: E,f..; L.Orig: E-? Fd3: Doc Type or Format Container File Folder Record Container Record (Title) Nu1: Number of pages Nu2: Doc Year Nu3: Doc Number 0 1948 26 Full GCG File Plan Code Record GCG File Plan Da1: Date Published Da2: Date Received Da3: Date Distributed Priority 21-0ct-1948 Record Type A04 Doc Item: E/ICEF1946 to 1997 Ex Bd DOS File Name Electronic Details No Document Alt Bar code = RAMP-TRIM Record Number CF/RAD/USAA/DB01/1997-05727 Notes Document Format Series/Year/SubSeries/Number/Rev: E/ICEF/1948/W.026; Doc Series/SubSeries/Year/Number/Rev:E/ICEF/W/1948/26 Doc Series: E/ICEF/W; Series Valid date on import: 01-Jan-1947; Doc Year: 1948; Doc Number: 0026; Doc Print Name of Person Submit Images Signature of Person Submit Number of images without cover iy>*L> «-*. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2009 UNICEF’S Mission Is To

ANNUAL REPORT 2009 UNICEF’s mission is to: Advocate for the protection of children’s rights, help meet their basic needs and expand their opportunities to reach their full potential; Mobilize political will and material resources to help countries ensure a ‘first call for children’ and build their capacity to do so; Respond in emergencies to relieve the suffering of children and those who provide their care; Promote the equal rights of women and girls, and support their full participation in the development of their communities; Work towards the human development goals, and the peace and social progress enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations. Front cover, main photo: © UNICEF/NYHQ2006-1470/Pirozzi Front cover, small photos, top left to bottom right: © UNICEF/NYHQ2005-1323/Tkhostova © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-1489/Holt © UNICEF/NYHQ2008-0800/Isaac © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-1841/Markisz Note on source information: Data in this report are drawn from the most recent available statistics from UNICEF and other UN agencies, annual reports prepared by UNICEF country offices and the June 2010 UNICEF Executive Director’s Annual Report to the Executive Board. Note on resources: All amounts unless otherwise specified are in US dollars. UNICEF ANNUAL REPORT 2009 Covering 1 January 2009 through 31 December 2009 CONTENTS Leading the UN mission for children 2 Celebrating 20 years of advancements in children’s rights 6 Making the best investment in human development: Children 11 Coming together and making the case 19 Unwavering in our commitment to children in crisis 25 Promoting gender equality as a child right 30 Transforming business systems for accountability and results 35 LEADING THE UN MISSION FOR CHILDREN n 2009, celebrations around the world marked the 20th anniversary of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC).