Neighborhood Perception As an Indicator of Gentrification in Central Zone of Belgrade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragan Kapicic Myths of the Kafana Life Secrets of the Underground

investments s e i t r e p o offices r p y r u x u l houses apartments short renting Dragan Kapicic Myths of the Kafana Life Secrets of the Underground Belgrade Impressions of the foreigners who arrive to Serbia Beach in the Centre of the City 2 Editorial Contents ife in Belgrade is the real challenge for those who have decided to spend part of their THEY SAID ABOUT SERBIA 04 lives in the Serbian capital. Impressions of the foreigners who arrive LReferring to this, one of our collocutors to Serbia through economic and in this magazine issue was the most emotional - Dragan Kapicic, one-time diplomatic channels basketball ace and the actual President of the Basketball Federation of Serbia. ADA CIGANLIJA Belgrade is also the city of secrets since 06 it has become a settlement a couple Beach in the Centre of the City of thousands years ago. Mysteries are being revealed almost every day. INTERVIEW The remains of the Celtic, Roman, 10 Byzantine, and Turkish architectures DRAGAN KAPICIC, are entwined with the modern ones The Basketball Legend that have been shaping Belgrade since the end of the 19th century. Secretive is also the strange world SPIRIT OF THE OLD BELGRADE 12 of underground tunnels, caves and Myths of the Kafana Life shelters that we open to our readers. Many kilometres of such hidden places lie under the central city streets and APARTMENTS 18 parks. They became accessible for visitors only during the recent couple short RENTING of years. 27 Also, Belgrade has characteristic bohemian past that is being preserved HOUSES 28 in the traditions of restaurants and cafes. -

Lawyers War with Ministry Paralyses Serbian Judiciary

the speech that Serbia’s Prime Min Prime Serbia’s that speech the from quotes the of one Bell but Dolly sought. lawyers the changes substantial the deliver not do provisions the ed that stat Lawyers SerbianChamberof the 30th, October on laws related ries and Nota on Law the to amendments the isworsening. ny image to London audience London to image sells reformist Vučić on Continued A conflict. the to befound urgently resolution must say experts accusations, bitter trade lawyers striking and ministry justice Serbia’s While Serbian judiciary paralyses ministry with war Lawyers “I Dimitar reformer. economic great region’s himself asthe rebrand to wants peacemaker’ Balkan ‘the that confirms LSE the to speech Serbian leader’s The Gordana Gordana COMMENT Although the government adopted adopted government the Although Bechev ANDRIĆ sic Do You Remember Remember DoYou sic clas 1981 Emir Kusturica’s from anecho isnot that No, things.” new learning day, every am changing as ever and the acrimo the and as ever away isasfar on ministry the with adeal strike, on inSerbia went yers law since 50days bout page 3 shiners face face shiners Belgrade’s Belgrade’s last shoe- last +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 oblivion Page 4 - - - - - - and underscoring the fact that the the that fact the underscoring and Parade Pride Gay recent the dled han government the how recalling freedom, media on questions tough off fending confidence, projected er 27 October Monday London School of Economics,LSE, on the at made Vučić, Aleksandar ister, 17 onSeptember onstrike went Serbian lawyers Facing a packed hall, Serbia’s lead hall,Serbia’s apacked Facing Issue No. -

Kategorije Atraktivosti Linija GS Beograd

LINIJE I KATEGORIJE ATRAKTIVNOSTI 27 Trg Republike - Mirijevo 3 407 Voždovac - Bela Reka SVE TRAMVAJSKE LINIJE 27 E Trg Republike - Mirijevo 4 503 Voždovac - Resnik AUTOBUSKE LINIJE: 32 Vukov spomenik - Višnjica 504 Kneževac - Resnik 24 Dorćol - Neimar 32 E Trg Republike - Višnjica 542 Miljakovac 1 - Petlovo Brdo 25 Karaburma 2 - Kumodraž 2 35 Trg Republike - Lešće 32 L Omladinski stadion - Lešće 37 Pančevački most - Kneževac 36 Trg Republike - Viline Vode - Dunav stanica 101 Omladinski stadion - Padinska Skela 42 Slavija - Banjica (VMA) 43 Trg Republike - Kotež 102 Padinska Skela - Vrbovsko 48 Pančevački most - Miljakovac 2 77 Zvezdara - Bežanijska kosa 104 Omladinski stadion - Crvenka 16 Karaburma 2 - Novi Beograd 96 Trg Republike - Borča 3 105 Omladinski stadion - Ovča 51 Slavija - Bele Vode Omladinski stadion - PKB Kovilovo 23 Karaburma 2 - Vidikovac 106 26 Dorćol - Braće Jerković 55 Zvezdara - Stari Železnik - Jabučki Rit 31 Studentski trg - Konjarnik 59 Slavija - Petlovo Brdo 107 PKB Direkcija - Dunavac 53 Zeleni venac - Vidikovac 60 Zeleni venac - Novi Beograd (Toplana) 108 Omladinski stadion - MZ Reva 58 Pančevački most - Novi Železnik 67 Zeleni venac - Novi Beograd (blok 24) 109 PKB Direkcija - Čenta 65 Zvezdara 2 - Novi Beograd 68 Zeleni Venac - Novi Beograd (blok 70) 110 Padinska Skela - Široka Greda 95 Novi Beograd - Borča 3 71 Zeleni venac - Bežanija (Ledine) 202 Omladisnki stadion - Veliko selo 17 Konjarnik - Zemun (Gornji grad) 72 Zeleni venac - aerodrom Beograd 302 L Ustanička - Restoran "Boleč" 18 Medaković 3 - Zemun (Bačka) 75 Zeleni venac - Bežanijska Kosa 54 Kanarevo Brdo - Železnik - Makiš 52 Zeleni venac - Cerak Vinogradi 88 Zemun (Kej oslobođenja) - Novi Železnik 57 Banovo Brdo - Naselje Golf 56 Zeleni venac - Petlovo Brdo 91 Glavna žel. -

Mass Heritage of New Belgrade: Housing Laboratory and So Much

PP Periodica Polytechnica Mass Heritage of New Belgrade: Architecture Housing Laboratory and So Much More 48(2), pp. 106-112, 2017 https://doi.org/10.3311/PPar.11621 Creative Commons Attribution b Jelica Jovanović1* research article Received 17 November 2017; accepted 06 December 2017 Abstract 1 Introduction The central zone of New Belgrade has been under tentative It might be difficult for us today to grasp the joy and enthu- protection by the law of the Republic of Serbia; it is slowly siasm of the post-war generation of planners and builders, once gaining the long-awaited canonical status of cultural prop- New Belgrade had started to emerge from the swampy sand erty. However, this good news has often been overshadowed of the left bank of the Sava river. The symbolic burden of the by the desperation among the professionals, the fear among vast marshland, which served as a no-mans-land between the flat owners and the fury among politicians: the first because Ottoman and Habsburg Empire, could not be automatically they grasp the scale of the job-to-be-done, the last because it annulled after the formation of the first Yugoslavia in 1918. interferes with their hopes and wishes, and the second because It took another twenty-something years, a world war and a they are stuck between the first and the third group. This whirl- revolution to get there. However, as well as the political and pool of interests shows many properties of New Belgrade, that economic issues, there was a set of organisational and techno- stretch far beyond the oversimplified narratives of ‘the unbuilt logical obstacles to creating this city. -

BENEFIT-GUIDE.Pdf

This Document / Email is for internal usage. This Document / Email is for internal usage. SERBIA DISCOUNT WITH TRIZMA BENEFIT CARD: Publishing house Laguna was founded in 1998. From the • Laguna`s editions - 25% modest beginnings with several • Other publishers - 10% published titles in a year, they • Gift program - 10% have come to the production of • Birthday discount (that over 300 published titles annually and thus are one of the largest day at max 3 Laguna publishing houses in the country, books) - 40% and in the region. Laguna has been successfully A discount can be obtained operating for more than 15 years by using the Trizma benefit and builds its reputation as a card and Laguna Readers publishing leader with proven club card in each Laguna values. During the many years of bookshop in all the cities in doing business, Laguna's interests are inextricably intertwined with Serbia. the interests of the people and the community in which it operates. To take over part of its own responsibility, Laguna has taken a strategic focus on continuous www.laguna.rs investment in the local community and local projects. This Document / Email is for internal usage. STARI GRAD DISCOUNT WITH TRIZMA NOVI BEOGRAD BENEFIT CARD: NOVI SAD 20% discount on medical Founded in 1994, after 12 years services: of successful work, VIZIM General medicine / Family polyclinic was re-registered as doctor Internal Medicine / the First Private Health Center Cardiology US Diagnosis Physical "VIZIM". VIZIM consists of more medicine and rehabilitation than 40 permanent medical Dentistry Gynecology Pediatric doctors and other medical Ophthalmology ORL technicians. -

MAPMAKING Ǩ ARCHITECTURE Ǩ URBAN PLANNING ABOUT US Practice and Expertise

MAPMAKING ǩ ARCHITECTURE ǩ URBAN PLANNING ABOUT US Practice and Expertise ABOUT US INAT is an international partnership with transdisciplinary teams based in Paris, Belgrade, Madrid and Hanoi. We provide our clients with innovative solutions adapted to their needs MAPMAKING through our creative research and development approach. Our experience encompasses ǩ,1$7PDSSLQJVWDQGDUG the fields of Mapmaking, Planninig and Urban design. ǩ3DULV ǩ7RN\R ǩ,QIRUPDWLRQV\VWHP Mapmaking Planning Urban design 3/$11,1* Schematic metro network diagrams Planning is a dynamic process of Successful urban environments are an essential tool for travelers discovery. It entails translating a become destinations when designed ǩ Existing network and authorities alike, they help the client's vision into a development to invite an abundance of foot traffic, ǩ Future network former navigate the transport strategy, providing a framework in programmed activities and lively network and the latter plan and which alternatives are evaluated, street scenes – combining develop- URBAN DESIGN implement urban development capacity in determined, feasibility is ment and open spaces to create an ǩ3XEOLFWUDQVSRUW policies. More importantly they are tested and a course is set - all with a exciting, viable neighborhood fabric. instrumental in shaping the identity single goal in mind – creating places Through careful planning and analy- ǩArchitecture and city of the city. These metro maps repre- where people make memories. sis, our urban projects are designed sent not only the structure of the to provide optimal benefits to the CONTACT urban fabric but reflect the paths of surrounding community while milions of people and their design addressing the complexities and and appearence is the most com- intricate relationships that tie our monly shared representation of the cities together. -

Modernism Versus Postmodernism As an Impetus to Creativity in the Work of Architects Milenija and Darko Marušić

SPATIUM No. 37, June 2017, pp. 12-21 UDC 72.071.1 Марушић М. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2298/SPAT1737012M72.071.1 Марушић Д. Original scientific paper MODERNISM VERSUS POSTMODERNISM AS AN IMPETUS TO CREATIVITY IN THE WORK OF ARCHITECTS MILENIJA AND DARKO MARUŠIĆ Dijana Milašinović Marić1 Kosovska Mitrovica, Department of Architecture, Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia Marta Vukotić Lazar, University of Priština, Faculty of Technical Science, with a temporary head office in Kosovska Mitrovica, Department of History of Art, Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia , University of Priština, Faculty of Philosophy, with a temporary head office in In light of the development of contemporary Serbian architecture in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the work of the team of architects Milenija and Darko Marušić is indicative of trends in Serbia’s Belgrade architectural scene. Their substantial and affirmed architectural activities encompass a series of issues and themes related both to the changes in Serbian architecture permeated with dialogues between modernism and postmodernism in the last decades of the twentieth century and to the specificity of the author’s contribution based on the personal foothold around which their architectural poetics weaves. The context of postmodernism, particularly the Neo-Rationalist European current, has been a suitable ambience in the genesis and upgrade of their creativity. It can be considered through several typical themes on the Modernism versus Postmodernism - relation, starting from the issue of contextuality as determination, through duality, mutual dialogue as an impetus, attitude about the comprehensiveness of architectural considerations based on the unbreakable link between the urbanism and architecture, and on the issues of urban morphology the theme oriented towards both the professional community and the wider public, but also towards architecture itself – its ethics and aesthetics, which are equally important themes for them. -

SPATIUM 28.Pdf

SPATIUM International Review ISSN 1450-569X No. 28, December 2012, Belgrade ISSN 2217-8066 (Online) SCOPE AND AIMS The review is concerned with a multi-disciplinary approach to spatial, regional and urban planning and architecture, as well as with various aspects of land use, including housing, environment and related themes and topics. It attempts to contribute to better theoretical understanding of a new spatial development processes and to improve the practice in the field. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PUBLISHER Miodrag Vujošević, IAUS, Belgrade, Serbia Institute of Architecture and Urban & Spatial Planning of Serbia, IAUS VICE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Igor Marić, Director Jasna Petrić, IAUS, Belgrade, Serbia ADDRESS Institute of Architecture and Urban & Spatial Planning of Serbia, IAUS SECRETARY "Spatium" Tamara Maričić, IAUS, Belgrade, Serbia Serbia, 11000 Belgrade, Bulevar kralja Aleksandra 73/II, tel: (381 11) 3370-091, fax: (381 11) 3370-203, e-mail: [email protected], web address: www.iaus.ac.rs IN PUBLISHING SERVICES AGREEMENT WITH Versita Sp. z o.o. ul. Solipska 14A/1 02-482 Warsaw, Poland FINANCIAL SUPPORT Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia EDITORIAL BOARD Branislav Bajat, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Belgrade, Serbia; Milica Bajić Brković, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Architecture, Belgrade, Serbia; Branko Cavrić, University of Botswana, Faculty of Engineering & Technology – FET, Department of Architecture and Planning – DAP, Gaborone, Botswana; Tijana Crnčević, IAUS, Belgrade, Serbia; Kaliopa Dimitrovska Andrews, Ljubljana, Slovenia; Zeynep Enlil, Yildiz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of City and Regional Planning, Istanbul, Turkey; Milorad Filipović; University of Belgrade, Faculty of Economics, Belgrade, Serbia; Panagiotis Getimis, Panteion University of Political and Social Sciences, Dept. -

ADVERTIMENT. La Consulta D'aquesta Tesi Queda Condicionada a L'acceptació De Les Següents Condicions D'ús: La Difusió D

ADVERTIMENT . La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX ( www.tesisenxarxa.net ) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA . La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR ( www.tesisenred.net ) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. En la utilización o cita de partes de la tesis es obligado indicar el nombre de la persona autora. -

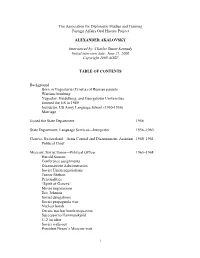

Akalovsky, Alexander

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project ALEXANDER AKALOVSKY Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: June 21, 2000 Copyright 2009 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Yugoslavia (Croatia) of Russian parents Wartime bombing Yugoslav, Heidelberg, and Georgetown Universities Entered the US in 1949 Instructor, US Army Language School (1950-1956) Marriage Joined the State Department 1956 State Department, Language Services—Interpreter 1956–1960 Geneva, Switzerland—Arms Control and Disarmament, Assistant 1960–1964 Political Chief Moscow, Soviet Union—Political Officer 1965–1968 Harold Stassen Conference assignments Disarmament Administration Soviet Union negotiations Turner Shelton Personalities “Spirit of Geneva” Movie negotiations Eric Johnson Soviet delegations Soviet propaganda war Nuclear bomb On site nuclear bomb inspection Successor to Hammarskjöld U-2 incident Soviet walk-out President Nixon’s Moscow visit 1 President Nixon Soviet leaders Khrushchev US visit John Foster Dulles Translation problems President Eisenhower Bordeaux Summit INTERVIEW [Note: This interview was not edited by Mr. Akalovsky] Q: Today is June 21, 2000. This is an interview with Alexander Akalovsky. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, and I’m Charles Stuart Kennedy. Shall we start? Could you tell me when and where you were born and something about your family? AKALOVSKY: I was born in what is now Croatia, on a little island called Rab, a beautiful place. The reason I was born there was that my parents left Russia after the revolution and they wound up on this island for a short time. My father was in the White Army, and then came to Yugoslavia. -

Newcomers Guide for Personnel Assigned to NATO MLO Belgrade Is Authored and Maintained by the Personnel of MLO

December 2017 NATO MILITARY LIAISON NEWCOMERS OFFICE 5 BIRČANINOVA STREET GUIDE 11 000 BELGRADE Serbia January 2018 NATO MLO BELGRADE Birčaninova 5 – Serbian MoD building Tel: +381 11 362 86 70 Fax: 00381 11 334 70 34 ARRIVALS GUIDE FOR NATO PERSONNEL The Newcomers guide for Personnel assigned to NATO MLO Belgrade is authored and maintained by the personnel of MLO. The objective of this guide is to assist new MLO members and their families during the relocation process and after arrival, by giving an overview of the procedures upon arrival and some basic information about the city and the office, to help you get started. The Arrivals and Staff Guide is not intended to provide a complete analysis of the subjects and was not written by legal experts. It is assembled through daily practice. The information is believed accurate as of the date of this guide, but is subject to change. Please suggest any sort of corrections and ammendments to this Guide. We look forward to meeting you! 1 NATO MLO Belgrade welcomes you! A word from our Chief: Welcome to the NATO Military Liaison Office in Belgrade. I hope that you find your stay in Belgrade rewarding and enjoyable and this Guide useful. You are now a member of NATO MLO BE and it is my job to support you throughout your time here. Arriving at any new job can be a daunting experience. Inevitably, there are a few administration and organization hoops to jump through in your first month or so and we will help you through these. -

Kvalitet Životne Sredine Grada Beograda U 2008. Godini

KVALITET ŽIVOTNE SREDINE GRADA BEOGRADA U 2008. GODINI GRADSKA UPRAVA gradA BEOgrad Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA JAVNO ZDRAVLJE REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL CENTER Beograd 2008 KVALITET ŽIVOTNE SREDINE GRADA BEOGRADA U 2008. GODINI Obrađivači: 1. Prim.dr Snežana Matić Besarabić (GZJZ) . poglavlje 1.1 2. Milica Gojković, dipl. inž . 3. Vojislava Dudić, dipl. inž . (Institut za javno zdravlje Srbije "Dr Milan Jovanović Batut") . poglavlje 1.2 4. Mr Gordana Pantelić (Institut za medicinu rada . i radiološku zaštitu "Dr Dragomir Karajović"). poglavlja. 1.3; 2.2; 2.5; 3.2 4. Prim. dr Miroslav Tanasković (GZJZ) . poglavlja 2.1; 2.3 5. Dr Marina Mandić (GZJZ) . poglavlje 2.4 6. Dr Dragan Pajić (GZJZ) . poglavlja 2.6; 3.1 7. Mr Predrag Kolarž, Institut za Fiziku . poglavlja 3.3 8. Boško Majstorović, dipl. inž (GZJZ) . poglavlje 4.0 9. Dr Milan Milutinović (GZJZ) . poglavlja 5.1; 5.2 Urednici: Marija Grubačević, pomoćnik sekretara, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Radomir Mijić, samostalni stručni saradnik, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Biljana Glamočić, samostalni stručni saradnik, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Branislav Božović, načelnik odeljenja, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Primarijus Miroslav Tanasković, Gradski zavod za javno zdravlje Ana Popović, dipl. inž, projekt menadžer, REC Suizdavači: Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine, Beograd Gradski zavod za javno zdravlje, Beograd Regionalni centar za životnu sredinu za Centralnu i Istočnu Evropu (REC) Za izdavače: Goran Trivan, dipl. inž, Sekretarijat za zaštitu životne sredine Mr sci med Slobodan Tošović, Gradski zavod za javno zdravlje Jovan Pavlović, Regionalni centar za životnu sredinu Fotografije Da budemo na čisto preuzete iz vizuelno-edukativno-propagandnog projekta .