Indecency Regulation and the End of the Distinction Between Broadcast Technology and Subscription-Based Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sex and Shock Jocks: an Analysis of the Howard Stern and Bob & Tom Shows Lawrence Soley Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Communication, College of Publications 11-1-2007 Sex and Shock Jocks: An Analysis of the Howard Stern and Bob & Tom Shows Lawrence Soley Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. Journal of Promotion Management, Vol. 13, No. 1/2 (November 2007): 73-91. DOI. © 2007 Taylor & Francis (Routledge). Used with permission. NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page. Sex and Shock Jocks: An Analysis of the Howard Stern and Bob & Tom Shows Lawrence Soley Diederich College of Communication, Marquette University Milwaukee, WI Abstract: Studies of mass media show that sexual content has increased during the past three decades and is now commonplace. Research studies have examined the sexual content of many media, but not talk radio. A subcategory of talk radio, called “shock jock” radio, has been repeatedly accused of being indecent and sexually explicit. This study fills in this gap in the literature by presenting a short history and an exploratory content analysis of shock jock radio. The content analysis compares the sexual discussions of two radio talk shows: Infinity’s Howard Stern Show and Clear Channel’s Bob & Tom Show. Introduction The quantity and explicitness of sexual content in mass media has steadily increased during the past three decades. Greenberg and Busselle (1996) found that sexual activities depicted in soap operas increased between 1985 and 1994, rising from 3.67 actions per hour in 1985 to 6.64 per hour in 1994. -

The Yes Catalogue ------1

THE YES CATALOGUE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Marquee Club Programme FLYER UK M P LTD. AUG 1968 2. MAGPIE TV UK ITV 31 DEC 1968 ???? (Rec. 31 Dec 1968) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3. Marquee Club Programme FLYER UK M P LTD. JAN 1969 Yes! 56w 4. TOP GEAR RADIO UK BBC 12 JAN 1969 Dear Father (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Anderson/Squire Everydays (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Stills Sweetness (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Anderson/Squire/Bailey Something's Coming (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Sondheim/Bernstein 5. TOP GEAR RADIO UK BBC 23 FEB 1969 something's coming (rec. ????) sondheim/bernstein (Peter Banks has this show listed in his notebook.) 6. Marquee Club Programme FLYER UK m p ltd. MAR 1969 (Yes was featured in this edition.) 7. GOLDEN ROSE TV FESTIVAL tv SWITZ montreux 24 apr 1969 - 25 apr 1969 8. radio one club radio uk bbc 22 may 1969 9. THE JOHNNIE WALKER SHOW RADIO UK BBC 14 JUN 1969 Looking Around (Rec. 4 Jun 1969) Anderson/Squire Sweetness (Rec. 4 Jun 1969) Anderson/Squire/Bailey Every Little Thing (Rec. 4 Jun 1969) Lennon/McCartney 10. JAM TV HOLL 27 jun 1969 11. SWEETNESS 7 PS/m/BL & YEL FRAN ATLANTIC 650 171 27 jun 1969 F1 Sweetness (Edit) 3:43 J. Anderson/C. Squire (Bailey not listed) F2 Something's Coming' (From "West Side Story") 7:07 Sondheim/Bernstein 12. SWEETNESS 7 M/RED UK ATL/POLYDOR 584280 04 JUL 1969 A Sweetness (Edit) 3:43 Anderson/Squire (Bailey not listed) B Something's Coming (From "West Side Story") 7:07 Sondheim/Bernstein 13. -

Bono, the Culture Wars, and a Profane Decision: the FCC's Reversal of Course on Indecency Determinations and Its New Path on Profanity

Bono, the Culture Wars, and a Profane Decision: The FCC's Reversal of Course on Indecency Determinations and Its New Path on Profanity Clay Calvert* INTRODUCTION The United States Supreme Court has rendered numerous high- profile opinions in the past thirty-five years regarding variations of the word "fuck." Paul Robert Cohen's anti-draft jacket,' Gregory Hess's threatening promise, 23George Carlin's satirical monologue,3 and Barbara Susan Papish's newspaper headline 4 quickly come to mind. 5 These now-aging opinions address important First Amendment issues of free speech, such as protection of political dissent,6 that continue to carry importance today. It is, however, a March 2004 ruling * Associate Professor of Communications & Law and Co-director of the Pennsylvania Center for the First Amendment at The Pennsylvania State University. B.A., 1987, Communication, Stanford University; J.D. with Great Distinction and Order of the Coif, 1991, McGeorge School of Law, University of the Pacific; Ph.D., 1996, Communication, Stanford University. Member, State Bar of California. 1. Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971) (protecting, as freedom of expression, the right to wear ajacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft" in a Los Angeles courthouse corridor). 2. Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105, 105 (1973) (protecting, as freedom of expression, defendant's statement, "We'll take the fucking street later (or again)," made during an anti-war demonstration on a university campus). 3. FCC v. Pacifica Found., 438 U.S. 726 (1978) (upholding the Federal Communications Commission's power to regulate indecent radio broadcasts and involving the radio play of several offensive words, including, but not limited to, "fuck" and "motherfucker"). -

“Thank You” to Your Service Customers with FREE SIRIUSXM

Say “thank you” to your service customers with FREE SIRIUSXM. Give them whatever they want to hear, whenever they want to hear it. Over 17,000 participating Dealers have already signed up. Your customers can receive a free 2-month trial subscription*† to our best package when they bring in their factory-equipped vehicles for service. The All Access trial subscription New Vehicles includes the widest variety of entertainment available in a car. Plus, they can enjoy SiriusXM on their phone and online, where they can create their own Certified Pre-Owned ad-free Personalized Stations Powered by Pandora, hear over 100 ad-free Xtra channels of music, watch SiriusXM video, and more. It’s all included in their trial and it’s at no cost to you or your customers. SXM Pre-Owned Program This exciting program is an easy way to augment your Service Customer Loyalty programs and show your customers your gratitude for choosing your Service Lane Program shop. Join today and we’ll notify your qualifying customers of their trial so they can start enjoying SiriusXM. PROGRAM BENEFITS Complimentary 2-Month Trial Subscription*† to the SiriusXM All Access package with over 150 channels of ad-free music, plus sports, news, talk and entertainment — no strings attached No cost to you or to your customer No Dealer effort required to activate the trial for Service customers HOW IT WORKS Join the free Service Simple one-time dealership opt-in process Lane Program today at Once SiriusXM receives your Service data, we will notify your eligible SiriusXMDealerPrograms.com customers of their trial, courtesy of your dealership and SiriusXM Same great programming for even more customers No dealer effort required to promote program or activate trials for Service customers MONTH Sign up and we will do the rest. -

China's Power Sector Heads Towards a Cleaner Future

EMBARGOED TO 10AM Beijing Time, 27 AUGUST 2013 CONTACT (China) Jun Ying, Bloomberg New Energy Finance +86 10 6649 7522 [email protected] CHINA’S POWER SECTOR HEADS TOWARDS A CLEANER FUTURE China’s power capacity will more than double by 2030 and renewables including large hydro will account for more than half of new plants, eroding coal’s dominant share and attracting investment of $1.4 trillion. China’s power sector carbon emissions could be in decline by 2027. Beijing, 27 August 2013 – China’s power sector is expected to go through significant changes through to 2030, according to a new report released by Bloomberg New Energy Finance. China will add 88GW of new power plants annually from now until 2030, which is equivalent to building the UK’s total generating capacity every year. China is already the world’s largest power generator and its largest carbon emitter. Over the next two decades China could add more than 1,500GW of new generating capacity and invest more than $3.9 trillion in power sector assets. However, as a result of shifts in generation mix, China’s total power sector emissions could start declining as early as 2027. Bloomberg New Energy Finance analysed China’s power sector based on four scenarios. In the central scenario, dubbed ‘New Normal’, China’s total power generation capacity more than doubles by 2030, with renewables including large hydro contributing more than half of all new capacity additions. This, together with an increase in gas-based generation, would drive the share of coal-fired power generation capacity down from 67% in 2012 to 44% in 2030. -

Digital Audio Broadcasting : Principles and Applications of Digital Radio

Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Digital Audio Broadcasting Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Copyright ß 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (þ44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (þ44) 1243 770571. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. -

Benbella Spring 2020 Titles

Letter from the publisher HELLO THERE! DEAR READER, 1 We’ve all heard the same advice when it comes to dieting: no late-night food. It’s one of the few pieces of con- ventional wisdom that most diets have in common. But as it turns out, science doesn’t actually support that claim. In Always Eat After 7 PM, nutritionist and bestselling author Joel Marion comes bearing good news for nighttime indulgers: eating big in the evening when we’re naturally hungriest can actually help us lose weight and keep it off for good. He’s one of the most divisive figures in journalism today, hailed as “the Walter Cronkite of his era” by some and deemed “the country’s reigning mischief-maker” by others, credited with everything from Bill Clinton’s impeachment to the election of Donald Trump. But beyond the splashy headlines, little is known about Matt Drudge, the notoriously reclusive journalist behind The Drudge Report, nor has anyone really stopped to analyze the outlet’s far-reaching influence on society and mainstream journalism—until now. In The Drudge Revolution, investigative journalist Matthew Lysiak offers never-reported insights in this definitive portrait of one of the most powerful men in media. We know that worldwide, we are sick. And we’re largely sick with ailments once considered rare, including cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. What we’re just beginning to understand is that one common root cause links all of these issues: insulin resistance. Over half of all adults in the United States are insulin resistant, with other countries either worse or not far behind. -

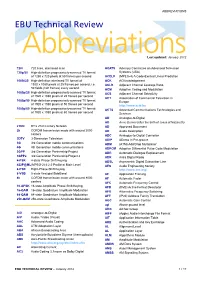

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

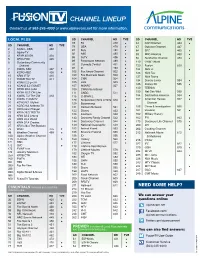

Channel Lineup

CHANNEL LINEUP Contact us at 563-245-4000 or www.alpinecom.net for more information. LOCAL PLUS SD CHANNEL HD TVE SD CHANNEL HD TVE 78 FX 478 44 Golf Channel 444 SD CHANNEL HD TVE 79 USA 479 47 Outdoor Channel 447 2 KGAN - CBS 402 81 Syfy 481 64 SEC 465 3 Alpine TV 85 A&E 485 83 BBC America 483 4 KPXR 48 ION 404 86 truTV 486 5 KFXA FOX 405 84 Sundance Channel 484 89 Paramount Network 489 6 Guttenberg Community 110 CNBC World Channel 91 Comedy Central 491 120 Fusion 520 7 KWWL NBC 407 93 E! 493 124 Nick Jr. 102 Fox News Channel 502 9 KCRG ABC 409 126 Nick Too 103 Fox Business News 503 10 KRIN IPTV 410 127 Nick Toons 104 CNN 504 11 KWKB This TV 411 134 Disney Junior 534 13 KGAN 2.2 getTV 105 HLN 505 136 Disney XD 536 14 KGAN3 2.3 COMET 107 MSNBC 507 140 TEENick 15 KPXR 48.2 qubo 109 CNN International 16 KPXR 48.3 ION Life 111 CNBC 511 150 Nat Geo Wild 550 18 KWWL 7.2 The CW 418 116 C-SPAN 2 154 Destination America 554 19 KWWL 7.3 MeTV 123 Nickelodeon/Nick At Nite 523 157 American Heroes 557 20 KCRG 9.2 MyNet 129 Boomerang Channel 21 KCRG 9.3 Antenna TV 131 Cartoon Network 531 158 Crime & Investigation 558 22 KFXA 28.2 Charge! 133 Disney 533 161 Viceland 561 23 KFXA 28.3 TBD TV 138 Freeform 538 162 Military History 24 KRIN 32.2 Learns 143 Discovery Family Channel 543 163 FYI 563 25 KRIN 32.3 World 26 KRIN 32.4 Creates 144 Discovery Channel 544 175 Discovery Life Channel 575 27 KFXA 28.4 The Stadium 149 National Geographic 549 200 DIY 75 WGN 475 153 Animal Planet 553 203 Cooking Channel 99 Weather Channel 499 155 Science Channel 555 212 Hallmark -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Internet Radio: an Analysis of Pandora and Spotify

Internet Radio: An Analysis of Pandora and Spotify BY Corinne Loiacono ADVISOR • Jim Bishop EDITORIAL REVIEWER • Phyllis Schumacher _________________________________________________________________________________________ Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors in the Bryant University Honors Program APRIL 2014 Internet Radio Customizations: An Analysis of Pandora and Spotify Senior Capstone Project for Corinne Loiacono Table of Contents Acknowledgements: ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract: ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction: ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Review of Literature: .................................................................................................................................... 7 An Overview of Pandora: ................................................................................................................ 7 An Overview of Spotify: ............................................................................................................... 10 Other Mediums: ............................................................................................................................. 12 A Comparison: .............................................................................................................................. -

Car Wash for Peace Page 1 of 5

Car Wash for Peace Page 1 of 5 Car Wash for Peace Chemicals New Construction Detailing Fast Lube Financing Insurance Management Self-Serve Tunnel Water Reclaim In The Lobby Home | Subscribe | Buyer's Guide | Welcome to the Industry | E-Books | News | Reader Services | Media Kit | Editor's Blog | Archives | Contact | Resources Quick Products Search A - L Quick Products Search M - Z Search Articles Email a Friend Print Bookmark Post Current Topics Comment Carwash Chemicals Construction Subscribe Today Home Detailing Subscribe Editor's Letters Editor's Blog Car Wash for Peace Environmental Issues Article Categories Jimmy Fallon and Mr. Squeaky team up to wash the Extra Profit Centers Fast Lube Buyer's Guide world clean Reader Services Finance Welcome to the Industry By Lacey Nadeau General E-Books In Bay Automatics Media Kit No more wars or dirty cars – Insurance that’s the theme behind News Laws and Regulations actor and comedian Jimmy Resources Fallon’s song called “Car Management Resource Directory Wash for Peace.” The tune Operator Profiles is catchy, the lyrics Perspectives Columns E-Books Archives sometimes goofy. But the Real Estate simple, two-verse song that Sales & Marketing Fallon plays on his guitar – Employment Self -Serve Carwashing on TV, YouTube, the radio Products and even at a Florida Tunnel Carwashing carwash – has more than a Water Issues politically obscure message behind it. Fallon’s proceeds from the single sold on Carwash Chemicals iTunes go to Fisher House, a charity that supports America’s military by providing homes that enable family Latest News Construction members to be close to their loved ones during hospitalization.