Mo Ving Forw Ard From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HBO S I LL BE GONE in the DARK Returns with a Special Episode June 22

HBO’s I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK Returns With A Special Episode June 22 The Story Syndicate Production Marks One Year Since The Guilty Plea Of Joseph James DeAngelo, The Golden State Killer I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK returns with a special episode directed by Elizabeth Wolff (HBO’s “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark”) and executive produced by Liz Garbus (HBO’s “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark,” “Who Killed Garrett Phillips?” and “Nothing Left Unsaid: Gloria Vanderbilt & Anderson Cooper). The critically acclaimed six-part documentary series based on the best-selling book of the same name debuted in June 2020 and explores writer Michelle McNamara’s investigation into the dark world of the violent predator she dubbed "The Golden State Killer.” This special episode debuts TUESDAY, JUNE 22 on HBO. Times per country visit Hbocaribbean.com Synopsis: In the summer of 2020, former police officer Joseph James DeAngelo, also known as the Golden State Killer, was sentenced to life in prison for the 50 home-invasion rapes and 13 murders he committed during his reign of terror in the 1970s and ‘80s in California. Many of the survivors and victim’s family members featured in the series reconvened for an emotional public sentencing hearing in August 2020, where they were given the opportunity to speak about their long-held pain and anger through victim impact statements, facing their attacker directly for the first time and bringing a sense of justice and resolution to the case. Writer Michelle McNamara was key to keeping the Golden State Killer case alive and in the public eye for so many years, but passed away in 2016, before she could witness the impact of her relentless determination in seeking justice for the victims. -

The Rainbow Comes and Goes a Mother and Son on Life Love and Loss by Anderson Cooper

The Rainbow Comes and Goes A Mother and Son On Life Love and Loss by Anderson Cooper You're readind a preview The Rainbow Comes and Goes A Mother and Son On Life Love and Loss book. To get able to download The Rainbow Comes and Goes A Mother and Son On Life Love and Loss you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited books*. Accessible on all your screens. *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every file is in the library. But if You are still not sure with the service, you can choose FREE Trial service. Ebook File Details: Review: WOW. What a great book and is worth a read. It’s sincere and everything that you would hope it would be. There are two aspects to this book, one is a candid conversation between a mother and a son, and the other is…well, a lot of the family gossip. It mirrors the conversations that many people hope that they have once in their lifetime with their... Original title: The Rainbow Comes and Goes: A Mother and Son On Life, Love, and Loss 304 pages Publisher: Harper; 1 edition (April 5, 2016) Language: English ISBN-10: 0062454943 ISBN-13: 978-0062454942 Product Dimensions:5.5 x 1 x 8.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 16507 kB Ebook File Tags: mother and son pdf, anderson cooper pdf, gloria vanderbilt pdf, comes and goes pdf, rainbow comes pdf, well written pdf, highly recommend pdf, back and forth pdf, really enjoyed pdf, enjoyed this book pdf, rich girl pdf, great read pdf, poor little pdf, easy read pdf, loved this book pdf, little rich pdf, good read pdf, enjoyed reading pdf, relationship between mother pdf, thoroughly enjoyed Description: #1 New York Times BestsellerA touching and intimate correspondence between Anderson Cooper and his mother, Gloria Vanderbilt, offering timeless wisdom and a revealing glimpse into their livesThough Anderson Cooper has always considered himself close to his mother, his intensely busy career as a journalist for CNN and CBS affords him little time to spend.. -

Cooper, Anderson (B

Cooper, Anderson (b. 1967) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Anderson Cooper. Entry Copyright © 2012 glbtq, Inc. Photograph by Flickr Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com user minds-eye. CC-BY- SA 2.0. Award-winning television journalist Anderson Cooper has traveled the globe, reporting from war zones and scenes of natural and man-made disasters, as well as covering stories on political and social issues. Cooper is a ubiquitous presence on American television, for in addition to being a news anchor, he also hosts a talk show. Cooper is the son of heiress and designer Gloria Vanderbilt and her fourth husband, Wyatt Cooper. In his memoir, Dispatches from the Edge (2006), Cooper stated that his parents' "backgrounds could not have been more different." Whereas his mother descends from one of American best-known and wealthiest families, his father was born into a poor farm family in the small town of Quitman, Mississippi. When he was sixteen he moved to the Ninth Ward of New Orleans with his mother and five of his seven siblings. Anderson Cooper wrote that his "father fell in love with New Orleans from the start" and delighted in its culture. After graduating from Francis T. Nicholls High School, however, Wyatt Cooper headed to California to pursue his dream of becoming an actor. Although he found work on both screen and stage, he eventually turned to screenwriting for Twentieth Century Fox. Wyatt Cooper and Vanderbilt married in 1964 and took up residence in a luxurious mansion in New York City. The couple had two sons, Carter, born in 1965, and Anderson, born on June 3, 1967. -

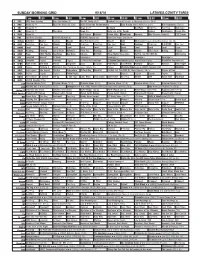

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

It Seemed Important at the Time: a Romance Memoir Free Download

IT SEEMED IMPORTANT AT THE TIME: A ROMANCE MEMOIR FREE DOWNLOAD Gloria Vanderbilt | 178 pages | 18 Feb 2011 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781439189825 | English | New York, NY, United States It Seemed Important at the Time: A Romance Memoir Show More. See More Categories. In romance what do you seek? As the author amply shows, her can-do attitude was daunted at times by racism, leaving her wondering if she was good enough. While Vanderbilt does a good job of listing some of the famous men she "dated" and married, the dirty details I was hoping for were just not there. Since then there have been many far more important court cases, but at the time it caused quite a stir. Not what I expected. Sign up and get a free eBook! Though Vanderbilt offers a psychological explanation for her constant quest for love, it seems more a perfunctory aside than a major revelation in this paean to the susceptible heart. There were only a few brief comments that referenced It Seemed Important at the Time: A Romance Memoir had children. Perhaps, but not as much as it did in Initially I thought I would read Vanderbilt's other works, but now I'm not It Seemed Important at the Time: A Romance Memoir sure. Name, rank and serial number -- that's about all. In the middle, there is a long string of conventional white men. Rating details. Why not put on a red silk gown, go to a fabulous party and make out with Gene Kelly? Stunningly beautiful herself, yet insecure and with a touch of wildness, she set out at a very early age to find romance. -

The Native American Fine Art Movement: a Resource Guide by Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba

2301 North Central Avenue, Phoenix, Arizona 85004-1323 www.heard.org The Native American Fine Art Movement: A Resource Guide By Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba HEARD MUSEUM PHOENIX, ARIZONA ©1994 Development of this resource guide was funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. This resource guide focuses on painting and sculpture produced by Native Americans in the continental United States since 1900. The emphasis on artists from the Southwest and Oklahoma is an indication of the importance of those regions to the on-going development of Native American art in this century and the reality of academic study. TABLE OF CONTENTS ● Acknowledgements and Credits ● A Note to Educators ● Introduction ● Chapter One: Early Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Two: San Ildefonso Watercolor Movement ● Chapter Three: Painting in the Southwest: "The Studio" ● Chapter Four: Native American Art in Oklahoma: The Kiowa and Bacone Artists ● Chapter Five: Five Civilized Tribes ● Chapter Six: Recent Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Seven: New Indian Painting ● Chapter Eight: Recent Native American Art ● Conclusion ● Native American History Timeline ● Key Points ● Review and Study Questions ● Discussion Questions and Activities ● Glossary of Art History Terms ● Annotated Suggested Reading ● Illustrations ● Looking at the Artworks: Points to Highlight or Recall Acknowledgements and Credits Authors: Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba Special thanks to: Ann Marshall, Director of Research Lisa MacCollum, Exhibits and Graphics Coordinator Angelina Holmes, Curatorial Administrative Assistant Tatiana Slock, Intern Carrie Heinonen, Research Associate Funding for development provided by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Copyright Notice All artworks reproduced with permission. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

Hemingway, Literalism, and Transgender Reading Author(S): Valerie Rohy Source: Twentieth Century Literature, Vol

Hemingway, Literalism, and Transgender Reading Author(s): Valerie Rohy Source: Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 57, No. 2 (Summer 2011), pp. 148-179 Published by: Duke University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41698740 Accessed: 09-06-2019 22:06 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Duke University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Twentieth Century Literature This content downloaded from 137.122.8.73 on Sun, 09 Jun 2019 22:06:57 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Hemingway, Literalism, and Transgender Reading Valerie Rohy F rom the 1980s to the turn of the twenty-first century, Hemingway studies underwent a fundamental revision, as new scholarship revealed unimagined complexities in the gendered life of the iconically masculine author. Reflecting the author s commodified persona, Hemingway s bi- ography always enjoyed a special status, but the confluence of his life and work reached a new intensity when an edited portion of The Garden of Eden appeared in 1986. Hemingway's manuscripts for the novel, expansive but unfinished at his death in 1961, showed the depth of his interest in homosexuality and the mutability of gender.1 As published, The Garden of Eden describes a young American couple on their honeymoon in Spain and the south of France in the 1920s; David is a writer distracted by his wife's exploration of masculinity, racialized fantasy, and lesbianism.2 Early in the narrative, Catherine surprises her husband with a haircut "cropped as short as a boy's" (14) explaining "I'm a girl, But now I'm a boy too" (15). -

Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century, 1991

BILLIE JANE BAGULEY LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES HEARD MUSEUM 2301 N. Central Avenue ▪ Phoenix AZ 85004 ▪ 602-252-8840 www.heard.org Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century, 1991 RC 10 Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century 2 Call Number: RC 10 Extent: Approximately 3 linear feet; copy photography, exhibition and publication records. Processed by: Richard Pearce-Moses, 1994-1995; revised by LaRee Bates, 2002. Revised, descriptions added and summary of contents added by Craig Swick, November 2009. Revised, descriptions added by Dwight Lanmon, November 2018. Provenance: Collection was assembled by the curatorial department of the Heard Museum. Arrangement: Arrangement imposed by archivist and curators. Copyright and Permissions: Copyright to the works of art is held by the artist, their heirs, assignees, or legatees. Copyright to the copy photography and records created by Heard Museum staff is held by the Heard Museum. Requests to reproduce, publish, or exhibit a photograph of an art works requires permissions of the artist and the museum. In all cases, the patron agrees to hold the Heard Museum harmless and indemnify the museum for any and all claims arising from use of the reproductions. Restrictions: Patrons must obtain written permission to reproduce or publish photographs of the Heard Museum’s holdings. Images must be reproduced in their entirety; they may not be cropped, overprinted, printed on colored stock, or bleed off the page. The Heard Museum reserves the right to examine proofs and captions for accuracy and sensitivity prior to publication with the right to revise, if necessary. -

The Szwedzicki Portfolios: Native American Fine Art and American Visual Culture 1917-1952

1 The Szwedzicki Portfolios: Native American Fine Art and American Visual Culture 1917-1952 Janet Catherine Berlo October 2008 2 Table of Contents Introduction . 3 Native American Painting as Modern Art The Publisher: l’Edition d’Art C. Szwedzicki . 25 Kiowa Indian Art, 1929 . .27 The Author The Subject Matter and the Artists The Pochoir Technique Pueblo Indian Painting, 1932 . 40 The Author The Subject Matter and the Artists Pueblo Indian Pottery, 1933-36 . 50 The Author The Subject Matter Sioux Indian Painting, 1938 . .59 The Subject Matter and the Artists American Indian Painters, 1950 . 66 The Subject Matter and the Artists North American Indian Costumes, 1952 . 81 The Artist: Oscar Howe The Subject Matter Collaboration, Patronage, Mentorship and Entrepreneurship . 90 Conclusion: Native American Art after 1952 . 99 Acknowledgements . 104 About the Author . 104 3 Introduction In 1929, a small French art press previously unknown to audiences in the United States published a portfolio of thirty plates entitled Kiowa Indian Art. This was the most elegant and meticulous publication on American Indian art ever offered for sale. Its publication came at a time when American Indian art of the West and Southwest was prominent in the public imagination. Of particular interest to the art world in that decade were the new watercolors being made by Kiowa and Pueblo artists; a place was being made for their display within the realm of the American “fine arts” traditions in museums and art galleries all over the country. Kiowa Indian Art and the five successive portfolios published by l’Edition d’Art C. -

B Y S U S a N D R a G

NATIVE AMERICANS AND WESTERN ICONS HAVE BEEN THE TWIN PILLARS OF OKLAHOMA’S CULTURE SINCE WELL BEFORE STATEHOOD. WE ASSEMBLED TWO PANELS OF EXPERTS TO DETERMINE WHICH BRAVE, HARDWORKING, JUSTICE-SEEKING, FRONTIER-TAMING INDIVIDUALS DESERVE A PLACE IN OKLAHOMA’S WESTERN PANTHEON. THE RESULT IS THE FOLLOWING LIST OF THE MOST INFLUENTIAL NATIVE AMERICANS, COWBOYS, AND COWGIRLS IN THE STATE’S HISTORY. BY SUSAN DRAGOO OklahomaToday.com 41 BILL ANOATUBBY BEUTLER FAMILY (b. 1945) Their stock was considered a CHICKASAW NATION CHICKASAW Bill Anoatubby grew up in Tisho- cowboy’s nightmare, but that mingo and first went to work was high praise for the Elk City- for the Chickasaw Nation as its RANDY BEUTLER COLLECTION based Beutler Brothers—Elra health services director in 1975. (1896-1987), Jake (1903-1975), He was elected governor of the and Lynn (1905-1999)—who Chickasaws in 1987 and now is in 1929 founded a livestock in his eighth term and twenty-ninth year in that office. He has contracting company that became one of the world’s largest worked to strengthen the nation’s foundation by diversifying rodeo producers. The Beutlers had an eye for bad bulls and its economy, leading the tribe into the twenty-first century as a tough broncs; one of their most famous animals, a bull politically and economically stable entity. The nation’s success named Speck, was successfully ridden only five times in more has brought prosperity: Every Chickasaw can access education than a hundred tries. The Beutler legacy lives on in a Roger benefits, scholarships, and health care. -

An American Writer Ernest Hemingway's Life Style and Its

НАУЧНИ ТРУДОВЕ НА РУСЕНСКИЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ - 2009, том 48, серия 6.3 An American writer Ernest Hemingway’s life style and its influence to his creative activity Ruslan Mammadov Abstract: This dissertation work gives a deeper view of the literary style and philosophy of Ernest Hemingway - the American short story writer, novelist, non-fiction writer, journalist, poet, and dramatist. Mainly, it focuses on the connection between the life of Ernest Hemingway and his literary works. He enjoyed life to the fullest and wanted to show that he could do whatever he wanted and it is truly obvious that these facts deeply influenced to his future career, his creativity and private life. This paper examines reflections of the author’s childhood on his works and the effects of women’s special role on his life and creativity and on the moral and ethical relativism of Hemingway's characters. It also studies the importance and the influence of World War I on his short stories and novels. What’s more, it studies his thirst for cultural knowledge which has left indelible signs in all of his works. The aim of this research is to find out essential features of the writer’s literary activity and to explain why the above coupled with the essential messages on the concept of wealth and goodness, portrayed in Hemingway's novels, are some of the reasons why his works have been rendered classics of the American literature. Key words: Ernest Hemingway INTRODUCTION Every man`s life ends the same way. It is only the details of how he lived and how 1 he died that distinguishes one man from another.