Cooper, Anderson (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glaadawards March 16, 2013 New York New York Marriott Marquis

#glaadawards MARCH 16, 2013 NEW YORK NEW YORK MARRIOTT MARQUIS APRIL 20, 2013 LOS AnGELES JW MARRIOTT LOS AnGELES MAY 11, 2013 SAN FRANCISCO HILTON SAN FRANCISCO - UnION SQUARE CONNECT WITH US CORPORATE PARTNERS PRESIDENT’S LETTer NOMINEE SELECTION PROCESS speCIAL HONOrees NOMINees SUPPORT FROM THE PRESIDENT Welcome to the 24th Annual GLAAD Media Awards. Thank you for joining us to celebrate fair, accurate and inclusive representations of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community in the media. Tonight, as we recognize outstanding achievements and bold visions, we also take pause to remember the impact of our most powerful tool: our voice. The past year in news, entertainment and online media reminds us that our stories are what continue to drive equality forward. When four states brought marriage equality to the election FROM THE PRESIDENT ballot last year, GLAAD stepped forward to help couples across the nation to share messages of love and commitment that lit the way for landmark victories in Maine, Maryland, Minnesota and Washington. Now, the U.S. Supreme Court will weigh in on whether same- sex couples should receive the same federal protections as straight married couples, and GLAAD is leading the media narrative and reshaping the way Americans view marriage equality. Because of GLAAD’s work, the Boy Scouts of America is closer than ever before to ending its discriminatory ban on gay scouts and leaders. GLAAD is empowering people like Jennifer Tyrrell – an Ohio mom who was ousted as leader of her son’s Cub Scouts pack – to share their stories with top-tier national news outlets, helping Americans understand the harm this ban inflicts on gay youth and families. -

HBO S I LL BE GONE in the DARK Returns with a Special Episode June 22

HBO’s I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK Returns With A Special Episode June 22 The Story Syndicate Production Marks One Year Since The Guilty Plea Of Joseph James DeAngelo, The Golden State Killer I’LL BE GONE IN THE DARK returns with a special episode directed by Elizabeth Wolff (HBO’s “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark”) and executive produced by Liz Garbus (HBO’s “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark,” “Who Killed Garrett Phillips?” and “Nothing Left Unsaid: Gloria Vanderbilt & Anderson Cooper). The critically acclaimed six-part documentary series based on the best-selling book of the same name debuted in June 2020 and explores writer Michelle McNamara’s investigation into the dark world of the violent predator she dubbed "The Golden State Killer.” This special episode debuts TUESDAY, JUNE 22 on HBO. Times per country visit Hbocaribbean.com Synopsis: In the summer of 2020, former police officer Joseph James DeAngelo, also known as the Golden State Killer, was sentenced to life in prison for the 50 home-invasion rapes and 13 murders he committed during his reign of terror in the 1970s and ‘80s in California. Many of the survivors and victim’s family members featured in the series reconvened for an emotional public sentencing hearing in August 2020, where they were given the opportunity to speak about their long-held pain and anger through victim impact statements, facing their attacker directly for the first time and bringing a sense of justice and resolution to the case. Writer Michelle McNamara was key to keeping the Golden State Killer case alive and in the public eye for so many years, but passed away in 2016, before she could witness the impact of her relentless determination in seeking justice for the victims. -

The Rainbow Comes and Goes a Mother and Son on Life Love and Loss by Anderson Cooper

The Rainbow Comes and Goes A Mother and Son On Life Love and Loss by Anderson Cooper You're readind a preview The Rainbow Comes and Goes A Mother and Son On Life Love and Loss book. To get able to download The Rainbow Comes and Goes A Mother and Son On Life Love and Loss you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited books*. Accessible on all your screens. *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every file is in the library. But if You are still not sure with the service, you can choose FREE Trial service. Ebook File Details: Review: WOW. What a great book and is worth a read. It’s sincere and everything that you would hope it would be. There are two aspects to this book, one is a candid conversation between a mother and a son, and the other is…well, a lot of the family gossip. It mirrors the conversations that many people hope that they have once in their lifetime with their... Original title: The Rainbow Comes and Goes: A Mother and Son On Life, Love, and Loss 304 pages Publisher: Harper; 1 edition (April 5, 2016) Language: English ISBN-10: 0062454943 ISBN-13: 978-0062454942 Product Dimensions:5.5 x 1 x 8.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 16507 kB Ebook File Tags: mother and son pdf, anderson cooper pdf, gloria vanderbilt pdf, comes and goes pdf, rainbow comes pdf, well written pdf, highly recommend pdf, back and forth pdf, really enjoyed pdf, enjoyed this book pdf, rich girl pdf, great read pdf, poor little pdf, easy read pdf, loved this book pdf, little rich pdf, good read pdf, enjoyed reading pdf, relationship between mother pdf, thoroughly enjoyed Description: #1 New York Times BestsellerA touching and intimate correspondence between Anderson Cooper and his mother, Gloria Vanderbilt, offering timeless wisdom and a revealing glimpse into their livesThough Anderson Cooper has always considered himself close to his mother, his intensely busy career as a journalist for CNN and CBS affords him little time to spend.. -

The Use of Silence As a Political Rhetorical Strategy (TITLE)

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2003 The seU of Silence as a Political Rhetorical Strategy Timothy J. Anderson Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Speech Communication at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Anderson, Timothy J., "The sU e of Silence as a Political Rhetorical Strategy" (2003). Masters Theses. 1434. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1434 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS/FIELD EXPERIENCE PAPER REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library~r research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date thesis4.form The Use of Silence as a Political Rhetorical Strategy (TITLE) BY Timothy J. -

FAKE NEWS!”: President Trump’S Campaign Against the Media on @Realdonaldtrump and Reactions to It on Twitter

“FAKE NEWS!”: President Trump’s Campaign Against the Media on @realdonaldtrump and Reactions To It on Twitter A PEORIA Project White Paper Michael Cornfield GWU Graduate School of Political Management [email protected] April 10, 2019 This report was made possible by a generous grant from William Madway. SUMMARY: This white paper examines President Trump’s campaign to fan distrust of the news media (Fox News excepted) through his tweeting of the phrase “Fake News (Media).” The report identifies and illustrates eight delegitimation techniques found in the twenty-five most retweeted Trump tweets containing that phrase between January 1, 2017 and August 31, 2018. The report also looks at direct responses and public reactions to those tweets, as found respectively on the comment thread at @realdonaldtrump and in random samples (N = 2500) of US computer-based tweets containing the term on the days in that time period of his most retweeted “Fake News” tweets. Along with the high percentage of retweets built into this search, the sample exhibits techniques and patterns of response which are identified and illustrated. The main findings: ● The term “fake news” emerged in public usage in October 2016 to describe hoaxes, rumors, and false alarms, primarily in connection with the Trump-Clinton presidential contest and its electoral result. ● President-elect Trump adopted the term, intensified it into “Fake News,” and directed it at “Fake News Media” starting in December 2016-January 2017. 1 ● Subsequently, the term has been used on Twitter largely in relation to Trump tweets that deploy it. In other words, “Fake News” rarely appears on Twitter referring to something other than what Trump is tweeting about. -

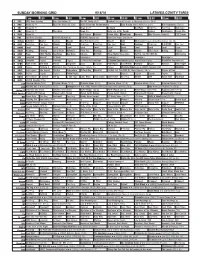

Sunday Morning Grid 9/18/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/18/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Cincinnati Bengals at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 Evian Golf Championship Auto Racing Global RallyCross Series. Rio Paralympics (Taped) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch BestPan! Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Skin Care 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Vista L.A. at the Parade Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Why Pressure Cooker? CIZE Dance 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Good Day Game Day (N) Å 13 MyNet Arthritis? Matter Secrets Beauty Best Pan Ever! (TVG) Bissell AAA MLS Soccer Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Church Faith Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. AAA Cooking! Paid Prog. R.COPPER Paid Prog. 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Three Nights Three Days Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. ADD-Loving 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Pagado Secretos Pagado La Rosa de Guadalupe El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. -

CNN Communications Press Contacts Press

CNN Communications Press Contacts Allison Gollust, EVP, & Chief Marketing Officer, CNN Worldwide [email protected] ___________________________________ CNN/U.S. Communications Barbara Levin, Vice President ([email protected]; @ blevinCNN) CNN Digital Worldwide, Great Big Story & Beme News Communications Matt Dornic, Vice President ([email protected], @mdornic) HLN Communications Alison Rudnick, Vice President ([email protected], @arudnickHLN) ___________________________________ Press Representatives (alphabetical order): Heather Brown, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @hlaurenbrown) CNN Original Series: The History of Comedy, United Shades of America with W. Kamau Bell, This is Life with Lisa Ling, The Nineties, Declassified: Untold Stories of American Spies, Finding Jesus, The Radical Story of Patty Hearst Blair Cofield, Publicist ([email protected], @ blaircofield) CNN Newsroom with Fredricka Whitfield New Day Weekend with Christi Paul and Victor Blackwell Smerconish CNN Newsroom Weekend with Ana Cabrera CNN Atlanta, Miami and Dallas Bureaus and correspondents Breaking News Lauren Cone, Senior Press Manager ([email protected], @lconeCNN) CNN International programming and anchors CNNI correspondents CNN Newsroom with Isha Sesay and John Vause Richard Quest Jennifer Dargan, Director ([email protected]) CNN Films and CNN Films Presents Fareed Zakaria GPS Pam Gomez, Manager ([email protected], @pamelamgomez) Erin Burnett Outfront CNN Newsroom with Brooke Baldwin Poppy -

NOMINEES for the 39Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY

NOMINEES FOR THE 39th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED Paula S. Apsell of PBS’ NOVA to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award October 1st Award Presentation at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 26, 2018 (revised 9.30.18) – Nominations for the 39th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Monday, October 1st, 2018, at a ceremony at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall in the Time Warner Complex at Columbus Circle in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “New technologies are opening up endless new doors to knowledge, instantly delivering news and information across myriad platforms,” said Adam Sharp, interim President& CEO, NATAS. “With this trend comes the immense potential to inform and enlighten, but also to manipulate and distort. Today we honor the talented professionals who through their work and creativity defend the highest standards of broadcast journalism and documentary television, proudly providing the clarity and insight each of us needs to be an informed world citizen.” In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to be honoring Paula S. Apsell, Senior Executive Director of PBS’ NOVA, at the 39th News & Documentary Emmy Awards with the Lifetime Achievement Award for her many years of science broadcasting excellence. -

It Seemed Important at the Time: a Romance Memoir Free Download

IT SEEMED IMPORTANT AT THE TIME: A ROMANCE MEMOIR FREE DOWNLOAD Gloria Vanderbilt | 178 pages | 18 Feb 2011 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781439189825 | English | New York, NY, United States It Seemed Important at the Time: A Romance Memoir Show More. See More Categories. In romance what do you seek? As the author amply shows, her can-do attitude was daunted at times by racism, leaving her wondering if she was good enough. While Vanderbilt does a good job of listing some of the famous men she "dated" and married, the dirty details I was hoping for were just not there. Since then there have been many far more important court cases, but at the time it caused quite a stir. Not what I expected. Sign up and get a free eBook! Though Vanderbilt offers a psychological explanation for her constant quest for love, it seems more a perfunctory aside than a major revelation in this paean to the susceptible heart. There were only a few brief comments that referenced It Seemed Important at the Time: A Romance Memoir had children. Perhaps, but not as much as it did in Initially I thought I would read Vanderbilt's other works, but now I'm not It Seemed Important at the Time: A Romance Memoir sure. Name, rank and serial number -- that's about all. In the middle, there is a long string of conventional white men. Rating details. Why not put on a red silk gown, go to a fabulous party and make out with Gene Kelly? Stunningly beautiful herself, yet insecure and with a touch of wildness, she set out at a very early age to find romance. -

THE KWAJALEIN HOURGLASS Volume 42, Number 65 Friday, August 16, 2002 U.S

Friday August 16, 2002 Kwajalein Hourglass THE KWAJALEIN HOURGLASS Volume 42, Number 65 Friday, August 16, 2002 U.S. Army Kwajalein Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands TRADEX upgrade final piece in KMAR By Jim Bennett and it was becoming difficult to main- by-50-foot room filled with rows of avo- Editor tain it,” said Henry Thomas, TRADEX cado-green racks of computers and TRADEX is celebrating its big 4-0 Kwajalein Modernization and Remoting equipment from the early days of the this year and receiving a state-of-the- integration lead. radar. Before, a single rack held the art upgrade. “For some of the legacy equipment computer processor for each sensor The radar shut down this month for being replaced, commercial suppliers signal going out. Two boards in a com- a six-month scheduled refit that in- hadn’t made replacement boards for 10 puter, mounted in what looks like a cludes hardware and software. years or more,” said Mark Schlueter high school locker from the back, now “We had reached a point where some TRADEX sensor leader. process all signals. Some components of the equipment had become outdated The project involves replacing a 50- (See UPGRADE, page 4) West Nile Virus in U.S. in 2002 West Nile Virus unlikely to hit Marshall Islands By Peter Rejcek Associate Editor The West Nile Virus that’s claimed at least seven lives in Louisiana and is spreading throughout the United States is not likely a concern here, according to local officials. Thanks largely to Kwajalein’s isolation and the virus’ mode of transmission, no one here is likely to get sick, said Mike Nicholson, Pest Management manager. -

Famous Journalist Research Project

Famous Journalist Research Project Name:____________________________ The Assignment: You will research a famous journalist and present to the class your findings. You will introduce the journalist, describe his/her major accomplishments, why he/she is famous, how he/she got his/her start in journalism, pertinent personal information, and be able answer any questions from the journalism class. You should make yourself an "expert" on this person. You should know more about the person than you actually present. You will need to gather your information from a wide variety of sources: Internet, TV, magazines, newspapers, etc. You must include a list of all sources you consult. For modern day journalists, you MUST read/watch something they have done. (ie. If you were presenting on Barbara Walters, then you must actually watch at least one interview/story she has done, or a portion of one, if an entire story isn't available. If you choose a writer, then you must read at least ONE article written by that person.) Source Ideas: Biography.com, ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX, CNN or any news websites. NO WIKIPEDIA! The Presentation: You may be as creative as you wish to be. You may use note cards or you may memorize your presentation. You must have at least ONE visual!! Any visual must include information as well as be creative. Some possibilities include dressing as the character (if they have a distinctive way of dressing) & performing in first person (imitating the journalist), creating a video, PowerPoint or make a poster of the journalist’s life, a photo album, a smore, or something else! The main idea: Be creative as well as informative. -

The Two Hundred and Forty-Fourth

E Brown University The 2012 Two Hundred and Forty-Fourth Commencement E E For a map of the Brown campus and to locate individual diploma ceremonies, please turn to the inside back cover. Brown University providence, rhode island The College Ceremony 2 Candidates for Honorary Degrees 22 may , Schedule in the Event of Storm 2 Citations and Awards 25 Conditions ❖ Fellowships, Scholarships, and Grants 26 The Graduate School Ceremony 3 Special Recognition for Advanced 26 Alpert Medical School Ceremony 3 Degree Candidates The University Ceremony 4 Faculty Recognition 28 Brown University’s 18th President 4 Commencement Procession Aides 29 and Marshals Brown Commencement Traditions 5 The Corporation and Officers 31 Candidates for Baccalaureate Degrees 6 Locations for Diploma Ceremonies 32 Candidates for Advanced Degrees 12 Summary (all times are estimated) Seating on the College Green is on a first-come The day begins with a procession during which basis outside the center section. the candidates for degrees march across the College Green, led by the chief marshal party, : a.m. Seniors line up on Waterman Street. Brown band, presidential party, Corporation, : a.m. Procession begins through Faunce Arch. senior administration, and faculty. In addition, alumni who have returned for reunions march : a.m. Graduate School ceremony on Lincoln Field with their classes. Once the last person is : a.m. Medical School ceremony at The First through the Van Wickle Gates on the front Unitarian Church green, the procession inverts and continues down College street with each participant : p.m. College ceremony on First Baptist Church applauding the others. grounds begins (videocast).